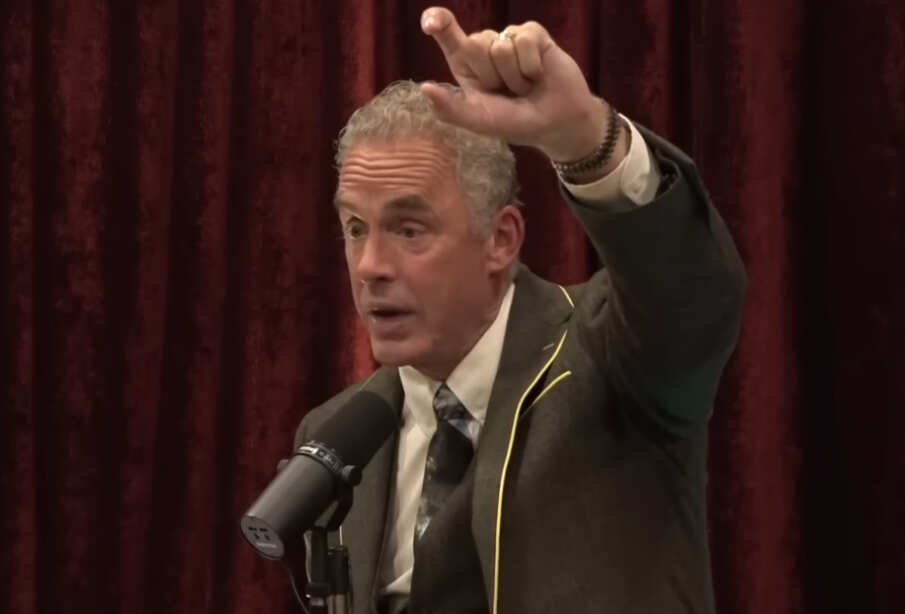

Read the full transcript of psychologist and author Jordan Peterson’s interview on The Joe Rogan Experience #2308, April 22, 2025.

Vanity and Head Injuries

JOE ROGAN: No, no, I’m too vain. That’s exactly right. I look back and I think, oh, those headphones are pushing at my hair. Isn’t that sad? Shave your head. That’s sad.

JORDAN PETERSON: You never look back if you do.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

JORDAN PETERSON: Oh, it’s the greatest thing in the world, freedom.

JOE ROGAN: I have a big dent here from when a meteorite landed on me when I was a kid.

JORDAN PETERSON: A meteorite? Oh, funny story. I know I’ve got plenty of cuts on my head. I got them all over the place.

JOE ROGAN: Well, you’re looking pretty unscarred.

JORDAN PETERSON: Oh, the back of my head. I have one when I was a little kid. It’s pretty big. One of these cranes that lifts up sewer pipes. Those big concrete pipes. Bang me off the back of the head. Yeah.

JOE ROGAN: Oh, yeah. That’s not good.

JORDAN PETERSON: Grayed out. Went to the hospital.

JOE ROGAN: Were you a different person before that experience?

JORDAN PETERSON: I don’t know. You’d have to talk to my mom. I was always a little wild.

JOE ROGAN: Autobiographical significance.

JORDAN PETERSON: Oh, there’s definitely a lot of head trauma.

JOE ROGAN: Were you knocked out?

JORDAN PETERSON: Personality? No, no. I stayed conscious, but I got close. I got gray. Everything. I grayed out. I came back to. I didn’t completely go unconscious.

O.J. Simpson’s Golf Clubs

JORDAN PETERSON: So Jamie went golfing this weekend with O.J. Simpson’s golf clubs.

JOE ROGAN: Oh, not with O.J. He’s not here.

JORDAN PETERSON: Jamie bought O.J. Simpson’s golf clubs after.

JOE ROGAN: This is like a childhood dream. No, they were just for sale. I saw them for sale.

JAMIE: I wanted some big grips. Yeah. A couple of my friends. What did Shane get? Shane got a bunch of stuff. Talked him into buying some stuff. Yeah, he got scarves and ties. He bought a bunch of ties. I think scarves, too.

JOE ROGAN: He bought a trophy.

JAMIE: A trophy and a Bill Clinton signed photo. And he spent thousands of dollars.

JOE ROGAN: What was this, some sort of O.J. Simpson auction?

JAMIE: Yeah, it was like an estate sale.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah.

JAMIE: Yeah. You know, he’s dead now, so you can get his stuff.

JOE ROGAN: Right. For nothing. Pennies on the dollar. Well, it’s—

JAMIE: I mean, only people like Jamie are dumb enough to buy. I was like, it’s for a goof. It’s one of those things, you’re getting it for a goof or you’re a very dark person.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, right. Yeah, right, right.

JAMIE: I wouldn’t want to own it even for a goof. If O.J. played pool, I wouldn’t want his cues.

JOE ROGAN: Was there cues?

JAMIE: No, there wasn’t. There was a weird notebook that Robert Kardashian had, handwritten stuff to him, blood splattered. I was like, whoa, that might be interesting, but it’s taking a vicious turn, Joe. Already.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah. That’s a dark story.

JOE ROGAN: It is, yeah. Yeah. And you only know the surface of it.

The O.J. Simpson Case and Planted Evidence

JORDAN PETERSON: Well, it’s dark in both ways. It’s also dark and planted evidence. You know, there was blood at the scene of the crime that had preservative in it. Allegedly. Supposedly. According to Robert Kardashian and according to, I believe, the forensic scientists, when they analyzed it, it matched O.J.’s blood.

But they had to draw blood from O.J. in order to determine whether or not it was his blood that was at the scene of the crime. And some of the blood found at the scene of the crime had that preservative in it that they use. They were sloppy in the 90s, you know, compared to now.

JOE ROGAN: Well, there was no DNA evidence back then. You know, people were—cops were there. There’s always going to be a certain percentage of cops that just want to convict somebody, regardless of the evidence. And if they’re, you know, in their mind, do they believe someone’s guilty, they’ll do whatever they can, including planting evidence, I guess. At least that’s allegedly.

I don’t—not that I don’t think he did it. I definitely think he did it, but I also think the cops planted evidence, which is probably at least partially why he got off. You know, I think the big reason why he got off was Rodney King.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right, right. Yeah. Right.

George Floyd and Complex Situations

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah. Have you gone into the whole George Floyd story at all? Have you ever looked at what they actually did to him? It’s a combination of things. What the cop did was horrible, but also he was dying. You know, most people probably, if they did that to you, you probably would have lived. You know, that guy had an allergic—he was f*ed up. But that cop did lean on his neck, which is always interesting to see people trying to minimize that. You know, I’m always like, you gotta be able to just say what it is.

JOE ROGAN: A situation can be ugly in a multitude of ways.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yes.

JOE ROGAN: Right. That’s when things get—well, that’s when it’s very difficult to pick your moral pathway forward. All your choices are not good.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yes. Which is oftentimes the case when it comes to conflicts.

JOE ROGAN: Right, yes.

JORDAN PETERSON: Conflicts are very complicated, and people want it to be binary. They want there to be a good guy and a bad guy, and that’s oftentimes not really the case.

JOE ROGAN: Well, it’s hard to organize yourself for combat unless you are quite convinced that you’re the good guy. So there’s a default to that dichotomy. That’s a necessary part of even standing your own ground. Right. Because otherwise you get demoralized.

And so I suppose people, well, when they’re threatened, they default to a simple narrative. And because that’s—you can’t defend yourself in some ways.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right.

JOE ROGAN: It’s very hard to defend yourself, especially physically or militarily, without a pretty cut and dried narrative.

Military Mindset and Moral Clarity

JORDAN PETERSON: Well, especially military operatives, you know, you have to have a very—your life and the people that you’re with, their life depends on you not having any confusion about whether or not it’s morally correct doing what you’re doing. That’s why they like to break it down to “kill bad dudes.” You know, kill bad dudes.

JOE ROGAN: Right.

JORDAN PETERSON: Real simple, let’s go. They tell us what to do, we do it, which is what you want to stay alive. You want your teammates stay alive. That’s what you have to do.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, well, you never know when doubt will cause a fraction of a second difference in reaction time.

JORDAN PETERSON: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. That’s always the thing with physical altercations with people too. You know, oftentimes people get sucked into these things where they’re not sure whether to act or not act, and that’s when they get in trouble.

JOE ROGAN: Right.

JORDAN PETERSON: You know?

JOE ROGAN: Right. That’s probably true in life. You don’t want to oversimplify things too. But once you’ve made a decision, well, that’s when it’s necessary to put doubts behind you, because otherwise you just act in half measures.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah. And oftentimes you have to have done the wrong thing before, failed to act or hesitate to act, and it cost you. And then you have to learn that lesson. It’s very difficult to know that without experiencing mistakes. You know, you have to have failed to act and then realize, oh, I should have done something there.

The Importance of Taking Action

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, well, that’s—I think that’s partly too—one of the things that I often faced in my clinical practice and with the students that I mentored was this confusion about acting. “I don’t know what to do. So what should I do? Well, nothing. I’ll wait around until I figure out what to do.”

It’s like, no, you should put together a bad plan and you should implement it. Because even if you fail in the implementation, you’ll gather information and then you can rectify the plan. And so staying in that malaise until you know what to do makes you get older and more miserable and you gather no information along the way.

A bad plan is a good idea best. You know, any plan is better than none. That’s a good rule of thumb. And a bad plan—a bad plan can be incrementally improved.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah.

JOE ROGAN: With experience.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right. He who hesitates is lost.

JOE ROGAN: Yep.

Modern Distractions and Young People

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, that’s really difficult for young people. I think more so today than ever at any time in history. Because the distractions are so many and they’re so engrossing. You know, if you get out of high school, you don’t know what to do and then you start playing video games and you’re on social media, a day can slip by like that.

A day becomes a week, becomes a month, becomes a year, and before you know it you’re 30.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah. Right.

JORDAN PETERSON: And you haven’t done sh.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah.

JORDAN PETERSON: And that’s really common. That’s really common today. And I don’t think we can ignore those factors. The factors of just engrossing distractions.

Algorithms and Short-Term Hedonism

JOE ROGAN: Yeah. Well, the algorithms optimized for short term attention. So you know, it’s a weird thing because you could imagine that you would want a machine that offers you what you want. Right. Because you want ads that are targeted to you. Because you don’t want to see a bunch of ads that aren’t relevant to you now and then, because maybe you’ll learn something and content.

Well, why not have a machine shovel the same sort of things that you are interested in at you? Yeah, that’s a kind of curation. The problem comes, and we haven’t figured this out at all technically and probably not psychologically, the problem comes in time frame. Right.

Because there’s a big difference between what you might be interested in if you were diligently striving towards a long term goal that required conscientiousness. And what’s going to attract your attention right now? This moment.

And the thing about the algorithms is that they maximize for short term attention and that’s a—so basically they’re actually optimizing for hedonism. And then you might say, well, so what? Because you’re getting what you want.

Well, the problem with short term impulsive hedonism is it doesn’t play out well over any reasonable time span. Yeah. That’s why you have to mature, which is painful and annoying, but absolutely necessary and much better than the alternative. The alternative is exactly what—that’s Peter Pan, right?

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah.

JOE ROGAN: Thirty year old, “I still haven’t grown up” and yeah, I’m a little past my shelf life now too.

Growing Up Doesn’t Mean Losing Fun

JORDAN PETERSON: I think people are afraid of losing fun. They think that when you grow up, you lose fun. But it’s silly, it’s not true. You can grow up and still have fun, you know, you just have to—you have to have discipline and prioritize your time.

JOE ROGAN: Well, that’s why Christ says to people that they have to become as little children, not stay—

JORDAN PETERSON: Right. You have to rediscover that, rediscover the joy of it. Yeah, but also, well, kids are good for that too, aren’t they?

Rediscovering Wonder Through Children

JOE ROGAN: Because they teach you that again, you look at the world through eyes of memory by the time you’re an adult, so the world loses its freshness. That’s part of—the world loses its freshness because you see your memories instead of the world.

And then kids come along and you think, oh, oh, yeah, that’s really actually quite interesting. And they’re so compelled by everything because their perceptions are so fresh that they share that with you. And that can help reawaken that spirit of childhood.

The Opposite of Tyranny is Play

Play, let’s say. I’ve been thinking a lot about play in the last year or so. Well, I spend a lot of time trying to take apart the causes of truly pathological degeneration. Right. On the sadistic side, on the criminal side, on the totalitarian side. Very curious about tyranny.

And it was very difficult for me to conceptualize the opposite of that as cleanly as I could characterize its presence. Like, what’s the opposite of tyranny? It’s not freedom, by the way. It’s certainly not anarchic freedom. It’s not hedonistic freedom, benevolence. I think it’s play.

JORDAN PETERSON: Play.

The Foundation of Play and Community

I think it’s play. Well, the developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, one of the things he pointed out was that—let’s say play is the foundation of micro community, right? When you’re a little kid, you play a game with another kid and then if that works, well, you inhabit a little dyadic community. You’re both in it together. And then if it really works, you replicate that across time and that gives you a friend.

But play is very interesting. It’s very interesting psychologically and psychobiologically because it has to be entered in voluntarily. You can’t force someone to play. And it’s also motivationally fragile. So mammals have a play circuit and it can be disrupted by pretty much any other motivational or emotional circuit. So the circumstances have to be set up properly. Like the walled garden. You know that idea. The walled garden is a place that play can take place, like, eternally, so to speak.

And because it has to be undertaken voluntarily, it’s the opposite of tyranny. My wife and I have really started to apply this in our marriage more consciously. Once I’d figured out this relationship, because I’ve been lecturing to people for a long time about how to conduct themselves in life so they don’t become a tyrant or a handmaiden to the tyrants. Right. A silent handmaiden to the tyrants, let’s say, and aiming at play.

You know, when we walked in here today, one of the things we said was, let’s have some fun. And I’ve been thinking this morning, too, about what attitude I should take coming in to talk to you. And there isn’t a better attitude. There isn’t a better attitude than play. And so, I think it is, because it’s the antithesis. It’s the antithesis of tyranny in particular.

And then you were talking more about mature play, and that’s that good. That also makes sense that this is the issue with the idea that adulthood isn’t any fun. It’s like, well, you want to play a simple game, or do you want to play a really sophisticated game, really? Well, now that’s going to require some discipline and some training and some maturation. But the payoff is much higher. That’s a good way to conceptualize marriage.

JOE ROGAN: The highs are higher when you’re successful.

JORDAN PETERSON: Well, and also the people who have the most sex now are religious married couples, really.

JOE ROGAN: I know. Isn’t that funny? Which religious, like—

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, good question, Joe. Good question. Well, I guess in the west, that would obviously be Christianity, but it’s an interesting case example of the sorts of things we’re talking about, because you can imagine at the dawn of the sexual revolution, when the birth control pill became prevalent, that the last hypothesis anyone would have possibly generated was that the cascading consequences of that over 50 years would be, well, radical increase in pornography use because sex has been made less dangerous by the pill, and that the people who were having the most sex would be really just married couples. Right.

The Sexual Revolution and Its Consequences

JOE ROGAN: But is that true? Because pornography essentially was very difficult to acquire before the birth control pill was invented.

JORDAN PETERSON: True, true.

JOE ROGAN: You used to have to go somewhere to get the pornography. Isn’t part of the excess use of pornography just because the access is so instantaneous now?

JORDAN PETERSON: Oh, definitely. But you could imagine too that you might have hypothesized that if the birth control pill took the threat out of sex, that pornography would be less necessary. That didn’t seem to work out.

JOE ROGAN: Right.

JORDAN PETERSON: So certainly the availability is—

JOE ROGAN: We would never know though, because the birth control was—when was it, 1960, something?

JORDAN PETERSON: That’s really when it started.

JOE ROGAN: Somewhere around then.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah. When it started to ramp up, let’s say.

JOE ROGAN: It’s so crazy because it completely changed the dynamic. Women could have sex for recreation with people that they didn’t even know and not have any consequences in terms of having to carry that person’s child. Whereas that was always a giant fear. If you’re a woman in the back of your head every time you have sex, you possibly could be taking care of a child for the next 18 plus years.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, yeah, well, that every time. Right, right.

JOE ROGAN: Take this thing, this is the consequential thing where with a guy, it’s like you have this biological imperative to spread your seed. But you’re not thinking about making babies.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right.

JOE ROGAN: You’re thinking about sexual activity. When a guy’s having sex, he’s not thinking, I can’t wait to make a baby. You’re just thinking, boy, sex is going to be great. I’m excited. Oh, boy, that’s fun. You’re not thinking, I’m making a kid. Because that would make you hesitant. And nature is not interested in hesitation. Nature’s like, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. Let’s just make you dumb as f* for about 20 minutes and focus on one goal.

Marriage and Commitment

JORDAN PETERSON: So why did you get married?

JOE ROGAN: Well, I love my wife. She wanted to get married. We had a child. It seemed like a good thing to do. It’s like at a certain point—

JORDAN PETERSON: Making—

JOE ROGAN: A baby is more of a commitment than getting married. You made a life, you know, like the commitment of getting married seemed right. Right, of course, but it’s also—

JORDAN PETERSON: But why did you stay committed then before the marriage? Once you had a child, I just—now you said you loved your wife.

JOE ROGAN: I love her. It’s a thing to do. It’s life. And raising a child became everything. It becomes a very different thing. Right. I think I have a lot of friends who don’t have kids and I’m not the type of person that thinks everyone should have a kid, you know, I know a lot of people with kids. They do say that. I don’t think everyone should have a kid. I think you should do whatever you want. I don’t know how your brain works. I assume your brain works along similar lines with me, but there’s a thing that happens when you—

JORDAN PETERSON: Scary thought, Joe.

JOE ROGAN: Similar lines, similar. I think we all share similar lines. There’s an empathy that comes from having a child that’s so different and an understanding that we are all babies that grew up. We all start off as these bundles of potential and genetics, and then we’re influenced by so many different things. There’s so many different factors, but I used to think of people as being grown up all the time.

And then when I had kids, I was like, we’re all just babies. We’re all just babies that have just been alive for a long time. You know, everyone started out as a baby, and it just profoundly changed the way I interact with people. The amount of compassion I have for people, the amount of charity that I have for people, the charitable way in which I think about them when they do something or they say something. I give people the benefit of the doubt way more.

Dave Chappelle said this to me once at the Comedy Store, and it was very profound. He said, “Having children didn’t just change the amount of love I have, it changed my capacity for love.” And I was like, ooh, that’s it. You just nailed it. You just nailed it. You know, because there’s private moments when you talk to people about their children, about having children and what that’s like. It’s a very psychedelic experience.

The Transformative Power of Parenthood

JORDAN PETERSON: That would be another reason why the family with children is the foundation of the community, has to be the foundation of the community. It’s kind of obvious from a biological perspective, let’s say no children, no community. But there’s no reason to assume that you wouldn’t get radically better at something with necessity and practice. And if you’re practicing loving your infant and your child, well, why wouldn’t that generalize? Why would that capacity develop?

JOE ROGAN: It’s not like a practice. It’s like an overwhelming desire that comes about. The love you have for your child is like—it’s not like anything else. It’s very different. It’s very—my friend Jim Brewer said this once. He said, “When I had a child, that’s when I really understood murder.” Really understood, like, my capacity to defend my child is like—I never understood, like, how could somebody kill somebody before? He was like, oh, now I get it. Now I get it.

And, you know, that’s real, too. And that’s also tribal, right? So it’s not just your child, it’s the child of everyone around you in your tribe. And then you think that you are being invaded by an oncoming tribe. And genetics and history dictates you have to be insanely ruthless to fight off that tribe. There’s no other way for survival, which is really wild, right? Because those people have that same feeling towards their children. It’s like that Sting line, “If the Russians love their children too.”

JORDAN PETERSON: So that love that you talk about with regard to your wife, you know, I asked you a little bit about that. It’s like I’ve talked to people who have—they can’t understand how someone could be with the same woman indefinitely. Let’s say these are people who usually haven’t been able to establish that within their own life. And of course, the price you pay, assuming it’s a price for foregoing all others, is that—well, that’s exactly it. It’s a major sacrifice.

And so what do you think? What role do you think that love plays? How do you conceptualize the relationship between that love that you described and that willingness to stay in a permanent relationship and that and the willingness also to not pursue any other women? How do you understand, how does that make itself manifest in your life? I mean, I presume that you—I presume that you know, you had opportunities of all sorts.

JOE ROGAN: I presume you do as well.

JORDAN PETERSON: In principle, I suppose they don’t seem to come to me.

JOE ROGAN: Back in the day, guys like you would be banging their grad students. Not guys like you, but guys in your—

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, yeah, well, there were guys.

JOE ROGAN: Wasn’t that always the thing?

JORDAN PETERSON: Yes.

JOE ROGAN: Fascinating aspect of—

JORDAN PETERSON: They seem to shut that off pretty much at the beginning.

Intellectual Rock Stars and Modern Relationships

JOE ROGAN: Well, they seem to have completely stopped that. Like if you go back to Feynman and Oppenheimer and famous, famous scientists were notoriously playboys, which is really interesting because it’s like these wild, innovative people were essentially intellectual rock stars, right? And then somehow or another that just got stopped.

Like if you were a professor in the 1960s, like the girls would be wooing the professor. They would be excited. These 22-year-old graduate students would be so excited to be talking to this incredibly famous intellectual. And they all, you know, were ladies men. Like Feynman was famous for chasing skirts. That was like part of the things. He does a lot of math and chases skirts.

You know, that is a giant distraction to people that are trying to get things done in life. And it’s also a distraction from your own personal development. I think. I think you could be with the wrong person and want to be with other people. And that makes sense. But really what that is is you should not be with that person anymore, which is unfortunately the case.

Like there’s a lot of guys who wind up with really hot women who are out of their f*ing mind. And a lot of women wind up with really hot men who are not what they thought they were going to be, you know, and if you find yourself in a situation where you’re with this pathological person and you’re trying to make it work and you realize at a certain point in time, like, I’m not going to make it work. Like this is—you have to be able to just jump ship.

That’s why people are hesitant to get married. That’s what really dangerous about marriage. It’s not like being with one person you really love being with. Like I really love being with my wife. She’s fun. Like we go, we have date nights all the time. We have a lot of fun, you know, we really do. It’s enjoyable.

Marriage and Commitment

JORDAN PETERSON: Why did you decide to set up date nights? How did you go about that? I mean, I know that’s personal, but I don’t want all the gory details.

JOE ROGAN: Let’s say no, it’s really simple. We just enjoy hanging out together. We have a lot of laughs. And so we just said, like, it’s kind of important because I’m so f*ing busy that we schedule time. That’s just unavoidable. Like, this is what we’re doing. We’re going to do this.

JORDAN PETERSON: And then we do it with Tammy, too. Yeah, we’ve done that for, like—

JOE ROGAN: I think most married couples will tell you that that’s important. Most married couples tell you that that’s kind of the secret. And it’s the secret.

JORDAN PETERSON: It’s like, shows are the best thing as well as being the secret.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, it’s fun. It’s fun. Like, if the person that you’re with is fun, that’s the real problem is that sometimes people just—they pick people that are hot. That’s it. You know, hot and willing and nice enough. Nice enough to be around. Then you deal with all the other crazy nonsense, and you’re setting yourself up.

I’ve had many friends ruin their f*ing lives, and then they go through divorces. And you’ve said this best, that one of the things that women are very good at is reputation destruction. I have seen that happen. So imagine you are legally entangled with someone who at one point in time, you loved intimately. And now that person is trying to destroy every aspect of your life.

And you have to pay for their lawyers. So you have to pay for the general of the army that’s trying to destroy your kingdom. And I’ve seen this happen to many of my friends. And that is why people are afraid of marriage. That’s why people are afraid of commitment. Because the disastrous implications of, like, what can happen if it goes sideways? Like, what can happen if you wind—

JORDAN PETERSON: Up hating each other?

The Cost of Divorce

JOE ROGAN: And what can happen if you just lie to yourself and you trick—like, some of the hesitation that I had for getting married is most of my friends that got married when I was young all went through horrible divorces. When I was on NewsRadio, Dave Foley, Stephen Root, and Phil Hartman were all going through it. All going through it in different levels of psychosis.

Obviously, Phil Hartman’s being the worst because his wife shot him when he was leaving her, by the way. He decided to leave her, and he tried to leave her a few times, and she shot him in his sleep, and then she shot herself. It’s a horrible, horrible story.

But Stephen Root went through it, and they—you know, they’d confide in me. I’d be like, oh, Jesus Christ. The amount of money these women were trying to get from them when they knew that they couldn’t afford this. So one of the dirty tricks that will happen with divorced lawyers, with people that are on sitcoms, is when you get on a sitcom, if you’re an actor and you get on a sitcom, it is the most stable job, the greatest job in show business for a lot of them, because you’re going to get a steady check, you’re going to do 24, maybe 26 episodes a year. You’re making more money than you’ve ever made in your whole life.

But then you get divorced. So what happens is it gets set up where your ex-wife wants a percentage of what you’re making at this very unrealistic level where you’re never going to achieve this again. And for Dave Foley, it was so bad that at one point in time, I don’t believe he was allowed to go back to Canada. I don’t know if that’s changed.

But the judge literally told him, when he told the judge, like, “I don’t have that kind of money anymore. I don’t have the potential for earning. I was on a hit sitcom, not even a hit sitcom, but I was on a sitcom and was it on NBC, paid a lot of money, and that was the only time I made that kind of money.” The judge said to him, “Your obligation to pay has no relation to your ability to pay.” That’s Canadian judges for you.

JORDAN PETERSON: Just insane. You know, those are words you never—those are words you never want to hear even once in your life.

JOE ROGAN: I love him. So I was going through this pain, not like he was, but just like, oh, my God. Oh, my God. So these three people that I was very close to, and then most of the other people that I knew, you know, I knew so many people.

Fortunately, my mother and my stepfather have a great relationship, and they have for a long time. So I had that modeled. Like, they were always very close and they didn’t fight, which is really nice. It was really nice to have that as a model, you know, like, where I realized, okay, everybody’s not at each other’s throats all the time. And some people actually do enjoy spending time together.

Modeling Healthy Relationships

JORDAN PETERSON: You know, Tammy and I on—on the tour, she started to introduce me two years ago and to talk about some of the things we’re doing in the family, some of our family business, talk about Peterson Academy, talk about essay. And so she’d go out on the—

JOE ROGAN: Stage and was that the first time she had ever gone on stage in front of you do enormous crowds?

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah. Well, so—so first of all she did that and then we replaced the business discussion because we were just doing an update about the family, you know, and so she’d do that. We replaced that with ads. And then she started to talk. She talked about the rules, say in 12 Rules for Life or some of the religious things I’ve been dealing with lately. And she’d relate that to something in her own life. And then she does the Q and A at the end of the lecture.

And part of that was just she was along with me and part of that was Mikhaila was introducing me for a while and then had to go back to her work. And so we slotted Tammy in because it seemed business decision.

But one of the things we figured out very quickly that was really a shock to us was that people really liked especially the Q and A’s when, because what people will offer their questions electronically on this platform called Slido, which is a very good platform for such things. And then Tammy would, they could upvote the questions and then Tammy would sort them and ask me questions kind of from the top down that were thematically relevant to the lecture that I had given.

But we found very quickly that people really liked that because they hadn’t seen a couple engage in civilized discussion ever. Seriously. It was really shocking, Joe. Like, you know, I was shocked when I first started touring by how demoralized people were like that. Really, that was really striking and painful to see that on such a mass scale.

And then also to see how little encouragement it took to have a really major effect. I mean, there’s a positive aspect to that too, but there’s also a tragic aspect. It’s like, you mean you just need to have some encouragement and that was enough. And you never got that like even once. That’s rough when you see that in thousands of people, right?

And it was the same thing. We found it was the same thing with regards to seeing a functional couple, at least even that model. Because, you know, Tammy asked me questions and she thinks about the questions and then sometimes she comments, but not that much, but she actually listens to the answers and she wants to hear the answer. And so, and that dynamic is being played out on stage and people found that very heartening.

And all that shows you—well, you said, you know yourself, and this is why I brought it up because you had the example from your, from your stepfather and your mom of this long term relationship that worked. How the hell do you orient yourself if you haven’t seen that anywhere, right?

JOE ROGAN: And then you consider relationships just like all the bad ones. And, like, you’re going to be burdened and locked into that. Did you ever see that video where Alec Baldwin and his wife are on the camp on red carpet, and they’re being interviewed and they’re asking them questions, and the wife starts talking, and Alec chimes in about something, and she said, “You’re not talking. I’m talking. When I’m talking, you’re not talking” on camera. And you watch this, you’re like, yo, that’s what everyone’s scared of, right? That’s right.

JORDAN PETERSON: Definitely. You want to talk about repetition, tyranny.

JOE ROGAN: The tyranny of being trapped in a relationship. Like, that is like—and sometimes one person is so overbearing that the other person just sort of submits to it.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right.

JOE ROGAN: And then you just like, I don’t even want to—I don’t want to fight. I don’t want to deal with this. I don’t want to deal with this. And so then you’re just trapped and this person’s insulting you and humiliating you publicly.

That was the case with Phil Hartman. I got to see that. We would all go—like, we went to a party once, and I remember she was talking about ex-boyfriends, that she loves pickup trucks because her ex-boyfriends had pickup trucks. And they would climb into the back of these pickup trucks. And I was like, what the f*? But she was doing it on purpose to, like, make him squirm and make him uncomfortable.

And she would say things like, talk about how he’s old. “Oh, he’s old. He doesn’t, you know, he doesn’t like to do anything.” It was just—it was just public humiliation in front of friends where you’re in this, like, arena where you—he can’t say anything. He can’t just go, “What the f* are you talking about? Like, why are you talking to me like that? Like, why are we doing this?” He can’t do that because he’s public and he’s out with us.

JORDAN PETERSON: Maybe he should do it anyways.

JOE ROGAN: Probably should do it anyways.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, probably.

JOE ROGAN: We’re all out. And, you know, Phil was all about, like, appearances.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right? Right.

JOE ROGAN: One of the things that he was afraid of with getting married was that he was just starting to break into films. And a lot of the films that he was doing were very, like, family friendly films. And it was—it helped that he was a family man, you know, if he was right.

JORDAN PETERSON: So he had—he had an act he had to sustain, too.

JOE ROGAN: He had an image.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right.

JOE ROGAN: And this was critical in Hollywood. Like, they had ideas of who you were. “Okay. You’re a family man. Okay, good, good, good.” So if you have this radical change in your life where no longer your family man, and if you want to be honest about it, and you want to say “I was in a toxic relationship and some of it was me and some of it was her, and this is what happened,” like, whoa, now you’re opening up the world to this big can of worms. Better to keep that can sealed.

Honoring Your Partner

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, well, it’s generally better not to have your—your fights in public. And it’s certainly better, you know, I mean, thinking about this commandment to honor your mother and father. And I’ve been thinking about what that means.

I read this book called Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt. And Frank had a really alcoholic father, like, like an Irish alcoholic father back in the 40s. Oh, yeah. He drank every cent the family had. And they, they lived in terrible poverty. And his sister died. And like, it was rough, but he said his father was often sober in the morning and, and he established a relationship with, like, good morning, sober father, and kind of put alcoholic, drunken, nighttime father in a different bin. And he could, he could get the benefit of having a father in consequence of that.

And that honoring, that’s also something that you want to do within a marriage. Right. Because your wife is your friend and your lover, but she’s also your wife and, and you’re her husband. And that means that a part of keeping that marriage working is honor. And part of the honor is that you don’t do that sort of thing in public.

JOE ROGAN: Right.

JORDAN PETERSON: Humiliated people fight in public. Well, that’s also in some ways independent. In a way, it’s independent of who your wife or husband is. It’s like, you know, you could imagine two people fighting in public, and one of them or both of them really deserving to have that fight as people.

But then to keep the marriage intact, you have to remember, well, this is my wife. She’s not just my friend. She’s not just someone I know. She’s my wife. And we shouldn’t be doing primate dominance hierarchy maneuvering in public. We shouldn’t be competing for power, because that’s going to destroy the marriage.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah.

JORDAN PETERSON: So that’s—that. That’s part of that honoring, I think, is to—to remember the role and to keep it, well, sacred is sacrosanct.

The Value of Respectful Communication

JORDAN PETERSON: Here’s another one. Don’t ever insult each other. Even though you want to, people get mean to you. You want to be mean back. I don’t do that with my friends, so I don’t do that with anyone else. I don’t want to do that. That’s why I don’t do it online. I don’t get involved in these hissy pissy fits online, particularly on Twitter.

I just don’t think the prime place for such things.

JORDAN PETERSON: That’s all it is. First of all, again, as someone who looks at everyone like a child or like a baby, I’m not angry that people do that. I understand the appeal of it. If I was 15 and Twitter was around, I would be tweeting at every celebrity saying, “You’re a loser. Jump in front of a bus.” I would say things just to try to get a reaction out of them. I think a lot of kids do. I think a lot of people don’t feel like they have a voice. And one way to be heard is to be insulting, and one way to be heard is to be negative.

If you look at the majority of discourse on social media in regards to hot button issues, it’s disrespectful, it’s contentious, it’s shitty and insulting. And I’ve decided over time in my life to not do that. I don’t want to do that. Not interested. I’m not interested in that kind of conflict.

I see real conflict all the time as an MMA commentator. I see the most violent legal conflict other than war all the time. That’s conflict. That’s real conflict and resolution and purposeful, agreed upon conflict. Regular back and forth. And wouldn’t it be better to figure out what you agree and disagree on and why and talk? Why can’t we all figure out how to do that? That should be a discipline you learn at an early age.

Most of the issues that people have, if the person comes at you insulting and aggressive, either that person is ignorant or they’re playing a game. And the game is to get your emotions up, to get you reactive and to be reacting to them instead of acting. The game is like if someone’s hyper aggressive in a fight, the game is to put you on the defensive so that they don’t. The best defense is a good offense. You learn that early on in fighting. So you learn that you can be very offensive and then the person never has a chance to get their game going.

That’s the case with conversations too. There’s a gamesmanship to this kind of communication, where it’s not just communicating, it’s essentially intellectual one-upsmanship and sparring. You’re sparring, you’re scoring points, you’re trying to dunk on each other. And I get that. I’ve done that before. I’ve engaged in it. It’s never satisfying. It always feels gross. Even if you win, it’s gross.

I said this before, even publicly, things that I felt like I had to do, like the Carlos Mencia conflict that I had way back in 2007, where I accused him of stealing material. And it became this viral video. And then a bunch of other comedians jumped in and we all agreed there was a real problem. It was a real problem because he was very famous and he was being protected by these agencies who were profiting off of him being famous. They didn’t want that train to stop.

I still to this day wonder if I would ever do that again. Because the negativity that came my way from people that were fans of his was so overwhelming. If you’re paying attention to it, it’s like, what did I open up? Even though I knew it was necessary. And that is also why people are negative. Because they want to stop you from engaging in conflict that’s going to hurt them. So they try to hurt you as much as possible. So you’re hesitant to do it. I don’t want to wade into those waters. It’s dangerous, filled with sharks.

Reputation and Status

JORDAN PETERSON: Well, you could imagine, maybe. I think this is worth delving into in some depth. You could imagine that there are various ways of attaining status, renown, reputation. Status isn’t exactly the right word because reputation is better, because you can have a reputation that you deserve. And so people do work for reputation. And all things considered, that’s a good thing.

JORDAN PETERSON: Earned reputation.

JORDAN PETERSON: Earned reputation. Earned reputation.

JORDAN PETERSON: Earned valid reputation with Jordan. That guy. That’s a unique human being. And that’s a real reputation.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right? Right. Okay.

JORDAN PETERSON: That’s what people want.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right, right. And it’s also, there isn’t anything more valuable that you can have than that. Not even close. This is why, by the way, this is very cool. It’s a bit of an aside, but it’s worth bringing up. In the Gospels, Christ tells people to store up treasure in heaven where it doesn’t rust, where the thieves can’t steal it. That’s reputational treasure.

So if you conduct yourself impeccably, you’ll develop a storehouse of reputation that will withstand all catastrophe. Nothing can touch it. There’s no place you can put your wealth that’s more effective than that. It’s the least violatable place. And that’s right.

And so, but the problem is, and this is a really tricky problem, and you’re touching on it, is that the reputation game can be gamed. So when your reputation rises, your serotonin levels rise, and that makes you less sensitive to negative emotion and more sensitive to positive emotion. So that’s a really good deal. And what that also means is that there’s a high psychological benefit to status increase, reputational increase, and a real cost to reputational decrease.

So that’s partly why people don’t like losing face, for example, because their emotions dysregulate. So now the best way to play that game is to establish a genuine reputation. And the best way to do that, you’ve done this, by the way. I figured out this year in my lectures that I’m always trying to answer a question on stage. So that’s a quest and I’m bringing the audience along on a quest, and it’s a real quest because I’m actually trying to figure something out and I do that in real time.

And that’s a very different game, that’s a very different conversational game than the status battle game. Because I could come on here, I don’t know if it would work, but I could come on here and I could try to show that I was smarter than Joe Rogan. Now, I’ve watched you and that’s a very difficult thing to pull off. But hypothetically, that could be my aim and I could play gotcha questions and I could lead you into…

JORDAN PETERSON: The problem is that wouldn’t work because I’m willing to accept that you’re smarter than me. First of all, I talk to a lot of people that are smarter than me and I like it. It’s enjoyable. I don’t ever feel uncomfortable talking to people that are smarter than me. I want to know some things that they can tell me. On certain things, I want to educate myself. I want to see how their mind works. I want to be blown away. I don’t want to compete with them intellectually. There’s times in my life where I would have fallen into that trap, I think.

JORDAN PETERSON: Well, I think that’s also what’s made you popular and a force for good, is that you are on a quest. And that quest, the consequence of that quest, if undertaken properly, is reputational enhancement. And people who can’t or won’t do that, they default to power games. And the part of it, and that’s the default to power. But it’s worsened with social media because if you meet someone and they’re playing a power game with you, you can just decide not to have anything to do with them anymore or you can put a stop to it if you need to.

But on social media you can’t because they’re distant from you and they’re often also anonymous. And so they can play power games to enhance their reputational status falsely with no consequences. And social media is rife with that. And it’s really a problem. I think that virtualization has enabled the psychopaths.

JORDAN PETERSON: Without a doubt.

Political Psychopathology and the Dark Tetrad

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah. Well, without a doubt that’s a terrible thing because the psychopathic types, they’re always the death of everything. I’m seeing this come up on the right now. So imagine this. I’ve been working on a new theory of political psychopathology and I like it quite a lot.

JORDAN PETERSON: Is this where the term “the woke right” comes in?

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, well, Lindsay is pointing at that, but he hasn’t got the diagnosis exactly right. So it isn’t woke. That’s not the issue. It’s not exactly one level.

JORDAN PETERSON: What he’s talking about is similar types of behavior.

JORDAN PETERSON: He is talking about that. Yeah, I know what he’s pointing at.

JORDAN PETERSON: “Woke” just lets you clarify in your head. Oh, it’s like that.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, but the problem is like Antifa. Absolutely. But the problem is that that argument is predicated on the claim that the ideas are the problem. Like the woke ideas, for example, on the right or the left. But that’s not the problem. The problem is that 4 to 5% of the population, something like that is Cluster B, that’s the DSM-5 terms: histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial, psychopathic. Or they have dark tetrad traits, they’re Machiavellian, they’re sadistic, that’s about 4%.

So the question is how do these people maneuver? And the answer is they go to where the power is and they adopt those ideas and they put themselves even on the forefront of that. But the ideas are completely irrelevant.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right?

JORDAN PETERSON: All they’re doing is they’re the Pharisees, they’re the modern version of the Pharisees. They’re the people who use God’s name in vain as they proclaim moral virtue. Doesn’t matter whether it’s right or left or Christian or Jewish or Islam. They invade the idea space and then they use those ideas as false weapons to advance their narcissistic advantage.

And so then you have the problem and the right’s going to face this more and more particularly because the left had to face it when they were in power.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yes.

JORDAN PETERSON: How do you identify the psychopathic parasites? 4% of the population who are clothed in your clothing and waving your flags, but who are only in it for narcissistic benefit?

The people who studied the dark triad, these were people who originally studied psychopaths and they moved into ordinary personality, so to speak. On the fringes showed that the non-criminal psychopaths, the fringe cases are Machiavellian, they use their language to manipulate. They’re narcissistic, they want unearned reputation. That’s what a narcissist wants. And they’re psychopathic, which makes them predators or parasites. That’s pretty bad, those three things.

But they had to expand the nomenclature after a while because they found that they were also sadistic, which implied that if you’re Machiavellian and narcissistic and psychopathic, you develop a sufficiently bad view of your fellow man that their undeserved pain is a source of pleasure to you. And that’s what’s being enabled online.

See, because we’ve evolved real specific mechanisms to keep such things under control in face-to-face interaction. Lack of anonymity, for example, within a community. Psychopaths in the real world, they wander. They have to move from place to place because people figure out who they are and they’re held responsible. They’re particularly held responsible by men.

But online they escape from that protective system of constraints and they have free reign and they can find other people like them very rapidly and they can gang together. And so I can really see this starting to happen on the right. I’ve been tracking psychopathic behavior on the right for probably four years, something like that. Especially on the anti-Semitic side because that’s really where it reared its head first.

JORDAN PETERSON: And why is that?

JORDAN PETERSON: There’s nothing more annoying than a successful minority right now. That’s part of it. I’m going to get myself in trouble right away too.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, for sure. Well, this is a real subject.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, it’s a real terrible subject. It’s interesting.

JORDAN PETERSON: If you don’t criticize it enough, you’re compromised. If you criticize, it’s like when it comes to anti-Semitism, it’s one of those things where you can’t separate. It’s a religion and it’s also a race and it’s also a government. That’s where things get weird.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right, right.

JORDAN PETERSON: And then there’s also the concept of intelligence agencies and compromise that also gets attached to it. The manipulation of world markets and money. And there’s a lot to unpack. And then there’s regular Jewish people who have nothing to do with that.

JORDAN PETERSON: Well, the Jews too are very successful. And so what you would expect from a purely statistical point of view is you’d expect them to be over-represented at the extreme.

JORDAN PETERSON: They’re also a walled garden, right?

JORDAN PETERSON: Meaning…

JORDAN PETERSON: Meaning it’s very difficult to join. They don’t proselytize, they don’t try to get you to join. And they’re all very tightly knit. They call themselves the Klan. They’re all locked in, you know, Jewish Klan, not KKK. The problem with that term, it’s been compromised by the Ku Klux Klan. But I mean it in terms of tribe.

JOE ROGAN: Community.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, community. They’re very tight knit in that regard. They stick together. And if you understand the history obviously of Nazi Germany and of persecution in Eastern Europe. Yeah, you have to. Yeah, of course.

Navigating Complex Conversations

JOE ROGAN: Yeah. Well, all these complex things are multi-dimensional. I watched your whole conversation with Douglas and I thought you guys did a very credible job, all three of you, of navigating unbelievably choppy waters. So that’s the first thing I’d like to say because one of the things I was trying to figure out when I was watching that is do I think I could have done a better job than any of you? And I certainly didn’t walk away from it with that idea in mind.

But then underneath all that, I thought there’s really an unbelievably tricky problem here. And I think that’s why it poked up into—well, you also set that conversation up, but it poked up and made itself manifest in that conversation. And the issue is how do you identify the psychopathic pretenders? And it’s even worse now and then make a barrier.

Right now the right was calling for the left to do that for decades and they didn’t and they couldn’t. And the left is not good at drawing barriers. Partly temperamentally, the right is somewhat better, but there’s no shortage of monstrosity there. And so then the question is, how do you draw the line? And that’s kind of what I was—because I’ve been watching these right wing—they’re not right wings—these psychopathic types manipulate the edge of the conservative movement for their own gain. And a lot of that’s cloaked in anti-Semitic guys. There’s plenty of anti-Semitism on the left too, by the way. So it’s not unique to the right.

JORDAN PETERSON: Particularly now.

JOE ROGAN: Yes, yes, particularly now. And so, you know, you’ve let your curiosity guide you. Your curiosity and your desire for knowledge. This quest, you’ve let that guide you as a podcaster. And I’m, by the way, I’m trying to work through exactly the same sort of thing.

How do you know, given your radical increase in stature over the last 10 years, how do you know when your curiosity and even your skepticism about the fact that things aren’t the way that people say they are? Because that’s certainly been demonstrated in the last 10 years. How do you—how should anyone decide what guardrails to put up? Like, what do you look for? Do you have a conceptual system worked out for that?

JORDAN PETERSON: Like, what do you mean? In what way? Well, how do I look for—in terms of people to talk to?

The Challenge of Platform Responsibility

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Because you have this insanely immense platform and you’re inviting people onto it. And, you know, you said to Douglas, and I know this to be true, that you’re not really thinking about the outcome. Exactly. You’re thinking about, this is an interesting person to talk to and I’d like to go on that quest.

But then you have the additional conundrum. We’re trying to work this out in the Daily Wire side of things, too. Not to say that that’s exactly the same situation. It’s like once you gain in reach and authority, then how do you know that? How do you take great care that the people you’re talking to aren’t—what would you say—eliciting or feeding a subculture. Yeah, that’s right. That hasn’t got the proper aims.

Like, I guess the legacy media probably worked that out by having people, mediators. Right. And guests. And that was also back when we could rely on structures of authority in some sense to filter. And now we’re in this helter skelter world where everything is the Legacy.

JORDAN PETERSON: The worst at that now.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, I know.

JORDAN PETERSON: They’re the worst.

JOE ROGAN: I know.

JORDAN PETERSON: Which is fascinating. You know, it really is. It’s really fascinating when you lose faith in a New York Times piece. You know, it’s like you go like, well, this is bullsht. Yeah, I know this. I know what they’re doing. I know they’re just, this is editorial bullsht. And that didn’t used to be the case, I don’t think.

JOE ROGAN: No, it didn’t.

Watergate and Intelligence Operations

JORDAN PETERSON: But then I go back to like what I learned about the Woodward, Bernstein, Nixon thing at Watergate. That was all essentially an intelligence operation. Have you ever looked into that? Yeah, I had Bill Murray on the podcast and Bill Murray said one of the wildest things. He read the first five pages of Bob Woodward’s biography on John Belushi, “Wired.” He read the first five pages like he goes, oh my God, they framed Nixon.

JOE ROGAN: Oh, really? Wow.

JORDAN PETERSON: Isn’t that crazy?

JOE ROGAN: Yeah. No.

JORDAN PETERSON: What they wrote about my friend was so not true. It was so wildly off. He said John Belushi was a lightweight. John Belushi’d have a couple of drinks and he’d be f*ed up. He wasn’t like a big partier that time he did that speedball, probably the only time he ever did it in his life. But Woodward had him painted as this maniacal, off the rails, just drug addled monster. And he knew that to not be true. He was very close to Belushi for a long time.

And so he was like, oh my God, they framed Nixon. Then when I told him the whole story, you know what Tucker Carlson had told me about Woodward being an intelligence asset. And then that was his first job ever as a journalist was Watergate, and that there’s FBI guys that were involved in it and the break in and the whole thing was tried. They tried to get Nixon out of there. The most popular president in the history of the country in terms of the vote. And they were successful. They got him out of there.

And it’s probably because, or likely because Nixon was very concerned with who killed Kennedy and he wanted to find out and he wanted to get that information out. And apparently he had been talking about it. I know who did it. And he was, you know, he didn’t want it happening to him, obviously, and he knew it could. If you’re a president, you know, a couple of guys ago, you know, just most—one of the most popular presidents, at least posthumously popular presidents. I know he’s very polarizing while he was in office, but was shot in the head in the middle of Dallas and you think that the government might have had something to do with it. Like that could—that could f* with your head, obviously, you know.

COVID Revelations

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, well, there—and there’s many things like that. I mean, you saw the government website that came up two days ago about COVID? Yes. Okay.

JORDAN PETERSON: Wild.

JOE ROGAN: Wild to see, that’s for sure. What are you supposed to do with that?

JORDAN PETERSON: All the things that would have gotten you fired if you were a professor and you said them four years ago, you would have 100% got fired for espousing any of these ideas that turned out to be true. You would have gotten kicked off of YouTube. You would have gotten—you know, there was a lot. There was a lot going on there, you know, which is—I feel so fortunate that right at the height of COVID was also when I had gone over to Spotify.

Spotify is a Swedish company. It’s different. They’re different. They don’t—they’re much more rational, and they’re not overwhelmed by this identity politics sh*t. And they aren’t overwhelmed by our weird political binary system of good guy, bad guy, depending on which side you’re on. And they were like, what are you talking about? Like, this is crap. We don’t—we don’t censor all the weeds also didn’t lock down.

JOE ROGAN: Yes, they didn’t lock down.

JORDAN PETERSON: They were also like, we don’t censor our rappers. Like, we don’t tell the—like, the rap lyrics. Some of my favorite rap lyrics are horrendous, but it’s just like my diet. My favorite movies are Tarantino movies. The dialogue is horrendous. It doesn’t mean that these are horrendous people that are putting together this. Tarantino’s a wonderful guy. He’s fun to be around. He’s great. I’ve had dinner with him, brought him to the comedy club.

JOE ROGAN: He’s great.

JORDAN PETERSON: He’s not a bad person. But he is an artist, and he’s creating this thing, and this thing is going to show you aspects of humanity that you know to be true but are horrific. That’s the same with rap lyrics. It’s the same with a lot of things. And Spotify’s position was, we’re not censoring. That’s not what we’re in the business of, like, promoting art. Like, we sell art and we’re not interested in censoring art, essentially.

And turns out, luckily, we were all right. We were all correct, you know, and now the government shows it on their f*ing website, which is crazy. Have you seen it? Jamie, pull it up because it’s bananas and—

JOE ROGAN: Well.

JORDAN PETERSON: And look at this lab.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, right. By the way.

Trump and the Vaccine Narrative

JORDAN PETERSON: You know, I know that he would bring up the vaccines when he was on his rallies, and people would boo. When he was on the campaign trail, people would boo. And I think he was, like, confused by that. I think he’s a little—I don’t want to say he’s out of touch, but there’s too many things for him to be thinking about, for him to be paying attention to what people really think about the vaccines and vaccine injuries and mandates and just the psychological warfare that was played on the American people.

You remember that very famous White House post that they made for the vaccinated, “You’ve done your job,” but for the unvaccinated, “You’re looking forward to a winter of severe illness and death. And the hospitals that you will overwhelm.” Like, that was the White House telling you something when it was in Omicron. By that point, which was like a cold, like it was crazy, the deaths had dropped off radically, but they were so in bed with the pharmaceutical companies that they were like, you gotta do it. You gotta get vaccinated.

And if you don’t, you’re looking forward to death and severe illness. Like, imagine this is—you’re not basing this on real statistics. You’re not basing this on science. You’re just basing this on this control, this fear element that you’re trying to impose upon people.

The Alliance for Responsible Citizenship

JOE ROGAN: Okay, so that’s—that’s an interesting point there, too, that issue of control and fear. You know, I started this—I was part of a group that started this organization in the UK called the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship. We had our second convention in November, which went very nicely, by the way.

JORDAN PETERSON: So you’re doing, like, a positive counter to the World Economic—

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, well, we have some rules, and one rule is you don’t use force or fear. Right. Use invitation. So can I tell you a story about that? Please do.

JORDAN PETERSON: Please do.

The Moses Story and Leadership Through Invitation

JORDAN PETERSON: Okay, so I’ve been touring about this new book of mine, right? We Who Wrestle with God. I’ve been lecturing about lots of the things I know, but I’ve been using biblical stories mostly to provide an analytical frame, because that’s what stories do. They provide a frame.

And there’s a great story in the continuing Exodus story, the story of Moses and the Israelites, where Moses has led his people away from the tyrant and away from their own slavery. Because there’s a dynamic in that story between those two things. No tyrants without slaves, or you might say, no tyrants without willing slaves.

And so the Israelites have to get away from the tyrant. But then it’s across the Red Sea of chaos and blood and into the desert for 40 years. You don’t escape from the tyrant if you’re a slave without paying a price. And maybe for three generations. It’s rough.

So Moses is trying to get these people to stop being slaves and to take responsibility so they don’t need a tyrant. And so he’s kind of got there and they’re on the edge of the promised land, right? And so they’re almost at the end of their voyage and they run out of water. They’re still in the desert. They run out of water.

And they get all whiny and bitchy about the fact that they had to go across the desert and it was way better under the tyrant and that Moses is nothing but a corrupt patriarch and he’s only power mad. And they foment some rebellion. And anyways, it’s a pretty ugly situation.

And the Israelites go to Moses and they say, look, we’re really starving. We’re thirsting for water. We’re going to die. Do you think you can have a chat with God, see if he’ll do something about this?

And God tells Moses to go to some rocks in the desert and to ask them to bring water forth. And so he goes with his people to these rocks, and instead of asking, he takes this staff of his. The staff is a really important thing. It’s your staff if you have an organization, same derivation, but it’s also the magic wand of Gandalf. It’s the flag you plant in new territory. It’s the Tree of Life. It’s the living tradition that has a spirit inside it.

And that’s a serpent, and that’s the serpent that eats all the serpents of the Egyptian tyrants’ magicians. That’s the staff. It’s his rod of his authority. And he, instead of asking the rocks, he hits them twice with the staff. So he forces them.

And God tells him that in consequence of that, number one, he’s going to die, and number two, he’s not going to get to the promised land. So there’s this insistence. It’s really interesting. Well, it’s crucial insistence. And it’s very important in this time, I think, to understand what this means.

So Moses is a leader. He’s the archetypal leader. And he realizes his responsibility in the encounter with the burning bush, which is something that attracts his attention that he takes with great seriousness and that transforms him. And so then he becomes the leader who stands up against the tyrant and frees the slaves and takes them through chaos into the desert.

And his temptation as leader is to use force. So when he’s a young man, for example, he kills an Egyptian aristocrat who was tormenting a Hebrew slave, and that’s why he has to leave Egypt. He’s tempted by power because he’s a leader.

And then at the end, even though he’s done all these things, he’s been an upstanding man and gone beyond his call of duty. And he’s right at the point where he attains victory, right, to enter the promised land. And he uses force once when God tells him to use invitation, to use his words, the Logos, to use words, to use invitation.

And that’s enough so that he’s dead, so is his brother Aaron. That’s his political arm. And he doesn’t enter the promised land. And then in the Gospels, of course, Christ forgoes power altogether. The temptation in the desert, one of the three temptations, is the temptation for use of power.

So one of the things that maybe we could conclude from all this, given the context of what you said, is that you can tell the tyrants, they use fear and compulsion and they don’t use invitation. So one of the rules we put together for ARK was invitation only play. We’re going to do this playfully.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah.

JORDAN PETERSON: And we’re not going to use force or fear ever. You have to use invitation. And so I don’t know what you think about that. Is a distinguish. Imagine it’s a distinguishing. It’s the distinguishing characteristic between the wannabe tyrants and the true leaders. The true leaders say, here’s an offer. Would you accept this of your own free will? And the tyrants say, the apocalypse is coming and everything. And we are allowed to do everything to forestall it.

JOE ROGAN: Right, right.

JORDAN PETERSON: Including control you and everything that you do.

JOE ROGAN: That’s the problem.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah.

JOE ROGAN: And that’s how they get people to fall in line. They fall in line through fear.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah. Yeah. Well, fear and force, it’s also, you know, you have to do this because the apocalypse is looming, which is always, in a way true.

JOE ROGAN: Always.

JORDAN PETERSON: There’s always. Well, there’s always an apocalypse of one form or another looming. The question is, what do you do about it?

JOE ROGAN: And terrifying anywhere in the world right now.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right.

JOE ROGAN: You might be experiencing the apocalypse right now. If you live in Gaza. Yeah, you might be experiencing the apocalypse right now, if you’re in Yemen, if you’re a Houthi.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right. The end of the world is always coming. Right. And for you, for me, for everybody. Yeah. Right. So you can always look into the future and conjure up an apocalyptic scenario. And maybe even that in itself isn’t a sin, although I think it is. There’s another. But if you yet then turn to fear and compulsion as your means of governance, then you’re a tyrant. I don’t care what your excuse is. It has to be invitational.

Fear and Compulsion as Tools of Tyranny

JOE ROGAN: That’s when it gets scary, when you see governments telling people that they have to fall in line, or these are horrible consequences for you not agreeing to what we’re saying.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, yeah.

JOE ROGAN: And then if you don’t do this, you’re a part of the problem.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right, exactly. Well, and if the apocalypse that’s generated in that way is of sufficient magnitude, there’s no limit to the amount of power that can be exerted. Right. Because obviously the rationale is there.

JOE ROGAN: They have to do it.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right.

JOE ROGAN: This is the rationale to stop Trump.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right.

JOE ROGAN: You’re trying to stop Hitler.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right? Right.

JOE ROGAN: Well, no matter what social white. Use the law. Use lawfare.

JORDAN PETERSON: Use whatever. Yeah, use whatever. This is one of the things that worries me about Canada at the moment. No, I know when we talked a couple of weeks ago, I expressed my concern about what was happening in Canada.

JOE ROGAN: Doesn’t look good.

JORDAN PETERSON: Well, I read Carney’s book Values. I read it twice, and I understood it. And Carney says in that book. Well, he says he’s an advocate of centralized planning, ESG. He was a huge ESG advocate. He organized many large corporations to go down this central planning governance route because the market wasn’t pricing everything properly. And so central planners had to step in.

And BlackRock and Vanguard and places like that were big parts of that. Don’t know if they were directly affected by Carney, but it’s the same thing, and they’ve stepped away from that. And he’s a big DEI advocate, and he’s also a net zero advocate.

And Carney says in his book, this is a good example of this, and I think also a good example of this kind of narcissism that we talked about earlier. Every single financial decision that every individual or organization makes has to prioritize decarbonization above all else, or else. And there will be many. He doesn’t say casualties, but he implies that there’ll be many. There’ll be many who pay a price along the way. But it’s necessary, you know, because you can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs.

And then he says 75% of the world’s fossil fuels have to stay in the ground. And this is who Canadians are seriously thinking about electing. Right.

JOE ROGAN: Why does he say the fossil fuels have to stay in the ground?

JORDAN PETERSON: Too much carbon, you know.

The Problem with Top-Down Narratives

JOE ROGAN: You know, the real problem with that is the same problem with the COVID narrative is that they don’t allow any dissent, they don’t allow any data that conflicts with the narrative. And they don’t want to look at any possible. Both of them are complicated. They’re not similar in a lot, but there are because they’re top down tyrannical.

JORDAN PETERSON: Tools using fear and compulsion.

JOE ROGAN: So they did during the COVID times. Nobody wanted to look at any alternative treatments. They didn’t want to look at health, metabolic health. They didn’t want to look at any factors other than vaccination and compliance with carbon. No one wants to look at. I’m sure you saw that Washington Post study of the last. Was it 50 million years? The graph that shows the temperature of Earth. Have you seen it? We’re in a cooling period.

And that was always what I mean. During the 1970s, Leonard Nimoy when he had that In Search Of show, one of the things that they covered was that we are at the verge of an ice age and how terrifying an ice age is.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah. Well, the conclusion you draw about climate and carbon dioxide is entirely dependent on where you put the origin point of your graph. So if you go back 150 years ago, carbon dioxide has increased. If you go back 500 million years ago, which is quite a lot longer, we’re in a drought, like a serious carbon dioxide drought.

JOE ROGAN: Right. And also carbon dioxide is the fuel of plants.

JORDAN PETERSON: Yes. It turns out that they like it. Well, you know, the global greening data. Well, when.

JOE ROGAN: Yeah, say it well, so people know it well.

The Global Greening Phenomenon

JORDAN PETERSON: You know, one of the things I learned as a scientist was that there’s usually an explanation or two that accounts for a phenomenon so completely that almost everything else is noise. Like the MAHA movement. Make America Healthy Again. The fundamental issue is insulin resistance. That’s the fundamental plague of, say, North America. And everything else is noise. It’s not unimportant noise, but insulin resistance is the major contributor.

On the climate side, when I look at the data, the thing that leaps out for me is greening. The planet is 20% greener than it was 30 years ago. Okay, 20%. This is NASA data. I’m not inventing this. Okay, and then the next you think, oh, 20%, if 20% of the plants had vanished, you’d be sure we’d heard about that. Yes.

Okay, so. And agricultural outputs got up 13%. Now, whether all that additional carbon dioxide is a function of human activity, that’s still debatable. Doesn’t matter. There is an association between the carbon dioxide rise and the plant propagation. Okay.

It’s even more particular than that because a lot of the greening has occurred in semi-arid areas, so areas around deserts. And the reason for that is that if there’s more carbon dioxide, the plants can close their breathing pores more and they don’t lose water.

And so not only is there 20% more vegetation, which is a lot, I think it’s twice the area of the United States that’s green. That’s a lot of green. And where our agricultural production is more effective. And the places that have greened were the very places that the deserts were supposed to expand into. And so, right, because they’ve greened, they’ve shrunk, not grown.

Now, you know, you could say, well, that rate of change has its problems and you know, rates of change have their problems, but I don’t see another data point that’s anywhere near as stunning as that.

JOE ROGAN: I think it’s a really important point. What you said that if we lost 20% of the plan, people would be freaking out.

JORDAN PETERSON: Oh, my God. Rightly so.

JOE ROGAN: Rightly so, but yet it’s not even discussed because again, it’s one of those things that invades the narrative.

JORDAN PETERSON: Right?

JOE ROGAN: It’s one of those pesky facts, those pesky truths that gets in the way of the thing that you’re saying, well, the apocalypse is coming.

The Climate Apocalypse Narrative and Power

JORDAN PETERSON: Yeah, well, that’s the thing about the narrative. Okay, so now we talked about the psychopaths who manipulate belief systems for their own advantage, right? The people who use God’s name in vain, the Pharisees who want to dress in religious clothing and obtain status in consequence. They’re Christ’s number one enemies in the Gospels, by the way. Those people, they’re the ones who conspire to crucify him. Right? The religious pretenders. So this has been going on for a very long period of time.

So the climate apocalypse narrative is perfectly situated to serve the purposes of the narcissists, the Machiavellians, the psychopaths and the sadists. Because it’s an infinitely expanding existential threat that can be used as an excuse for anything. And it also provides a perfect cloak for any amount of power maneuvering.

It’s like I want to make your shower heads put out a needle spray so that you’re cold all the time while you have a shower, while you’re doing something you do every day that could otherwise be highly enjoyable. Why do I get to invade your life to that degree? Well, because the planet’s at stake, Joe. And who are you to privilege your shower comfort, something that trivial, over the fate of the entire planet? Well, you can use that argument at every single level.

You know, Trump came out with this executive statement just a few days ago about shower heads, and everybody kind of laughed about that. And I thought, no, he has an eye for petty tyranny. For petty tyranny. And there’s very little that’s more petty than, well, I think the showerhead example is a perfect one. And then you also think, look, if they’re willing to control your life at that level of detail, what are they not willing to control? It’s like you’re concerned about my shower heads? We’re out of water, which we’re not at all. So what won’t you control?

So you think all the psychopaths are edge cases? They’ll move wherever the power is. They find a narrative that can be used to strike fear in the hearts of people and to justify compulsion. They ally themselves with that belief claim, and then they ratchet themselves up status hierarchies without any true reputational validity, riding on that edge of fear and power.

I wrote an article. It hasn’t been published yet in the Telegraph because I got a lot of hell after one of our podcasts. You may know this, but the climate change stuff. That’s right. The whole transcript was sent to the college as an indication that I was out of my wheelhouse. And maybe I stepped a bit out of my wheelhouse when we had that discussion, because I’m not a climate scientist, whatever the hell that is, by the way. Because you have to know a lot to be a climate scientist and an economist on top of that.

So today I’m talking about something that’s a lot more psychological. The climate apocalypse narrative is a social contagion that’s driven by power-mad psychopaths who are hell-bent on using fear and compulsion to make sure everyone steps in line so that they can continue with their acquisition of undeserved power.

JOE ROGAN: It’s also effective enough that the people that are underneath the power comply and do the job of the man for the man.