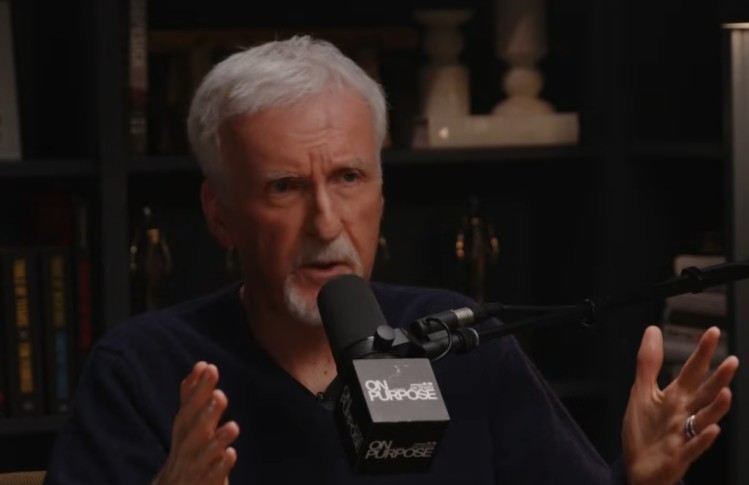

Here is the full transcript of filmmaker James Cameron’s interview on On Purpose Podcast with host Jay Shetty, December 22, 2025.

Brief Notes: In this extraordinary episode of the Jay Shetty Podcast, visionary filmmaker James Cameron dives deep into the creative fire behind his record-breaking career and the highly anticipated Avatar: Fire and Ash. Cameron reflects on his humble beginnings as a truck driver with a dream, sharing how his obsession with world-building and nature eventually led him to risk everything on films like Titanic [54:02]. He offers rare insights into the “slow boil” of his writing process, the role of dreams in his imagery [19:11], and why he believes the greatest risk for any artist is to stop taking them [53:26]. From the evolutionary intelligence of whales to the profound human need for connection, this conversation is a masterclass in the duty of storytelling and the power of empathy [01:27:15].

The First Spark of Imagination

JAY SHETTY: Do you remember the first character or world that you ever imagined, even if it wasn’t for a movie or a film or an idea, but just a world that you lived in when you were younger?

JAMES CAMERON: Well, I was totally enamored as a kid with anything fantastic or science fiction, anything I saw on television that was fantasy and science fiction. But I remember one sort—I think there’s a moment where something inspires you to take your own action, to do your own art.

And I remember, and this may not have been the first, but this is what pops to mind: seeing Mysterious Island, which was a Ray Harryhausen film. I probably would have been seven or eight and coming home and wanting to do my own version of Mysterious Island.

So technically, that would be the first case I can remember of world-building inspired by something else, but not copying that thing. And, of course, Ray Harryhausen was always inspiring to me as a kid. I mean, the technique that he used of stop motion animation is considered quite quaint now, and we can do things that are far more realistic. But at the time, there was nothing like that in terms of his art, his craft. And that blew my mind at the time.

And look, it doesn’t take much to inspire. Kids are imaginative, and when you get something that impacts your imagination and triggers it, and then you start to draw, all of a sudden my hand’s going. You know what I mean? I’m drawing. I’m choosing colors. What color do I want the giant turtle to be? I picked green. No big surprise there.

JAY SHETTY: Did you ever get to share that with the director or anyone in the cast?

JAMES CAMERON: I did talk—I talked to Ray later in his life. He was pretty retired. He hadn’t done any stop motion for some time. But I shared with him some of these early stories and the impact he had on me and so many other filmmakers. He was absolutely the most fantastic of the fantasy filmmakers that were out there for many, many years.

JAY SHETTY: I can’t imagine what that felt like to him, to hear that something of his had inspired you to go on to see what you did.

JAMES CAMERON: I think he was just kind of dazzled by where the next generation and the one after that had sort of taken it into CG and so on and things that he couldn’t have imagined—the technology. But he certainly could have imagined the design and the storytelling that were possible with those new tools.

The Ripple Effect of Art

JAY SHETTY: Yeah, no, I think that’s the power of art. As I’m listening to you, I’m thinking just how many young kids are going to go and watch Fire and Ash and that becomes their version of that movie that then inspires them to go and bring their art into the world, whether it’s film and TV or poetry or music or whatever it may be and how important it is. Because he probably didn’t imagine that James Cameron as a seven or eight year old was watching his film.

JAMES CAMERON: Oh, how could he have? I mean, he was just following his muse and we all do. But I’d love to think that stuff that I’ve done has inspired—I want to say kids, but it could be anybody that wants to be an artist at any age.

And I have this art show that’s touring around in Europe. It’s actually in Istanbul right now. And it’s a lot of drawings that I did and paintings that I did when I was in high school and in college. I didn’t know I was going to be a big shot filmmaker someday. How could you possibly know that? I was just—the ideas in my head, I just had to draw them. I mean, I had to draw them.

And I always say artists are the people that can’t not draw or can’t not create. It’s not like you force yourself to create. You have to force yourself not to. And if that’s flowing from you, if it’s flowing from your fingertips or if it’s voice or if it’s music or whatever it is, if it’s flowing from you and you can’t stop it, guess what? You’re stuck.

JAY SHETTY: You’re an artist and you feel compelled.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah, yeah. And you don’t question it. That’s the crazy thing. At least I never did. I’d sit on the quad at college and I’d just have my math notebook or whatever and I’d be sketching some girl sitting under a tree or some guy, or my own hand. I mean, it was just always drawing. I couldn’t imagine not drawing.

The Solitary Creative and the Social Organizer

JAY SHETTY: Was there a part of you that felt out of place as a kid, but now that same skill is essential to who you are now? Or did you always feel that?

JAMES CAMERON: I think so. Yeah. I mean, look, it can get very solitary, the creative act, especially when you write because you really have to just isolate. And you need to be in your own headspace and be comfortable there for long periods of time. So it can be isolating.

I remember—and our memory of our childhood is always tainted by the stories that we tell ourselves. And we don’t remember the event, we remember the story.

JAY SHETTY: Very true.

JAMES CAMERON: Because memory is an interesting thing. We don’t really—we’re not video cameras. There isn’t enough storage in this three and a half pound meat computer to last a lifetime. It’d be a million petabytes of data. We just don’t have room for that. So we don’t remember the event like a videotape. We remember the story we tell ourselves.

The story I tell myself is that I spent a lot of time on my own, in my imagination, in the woods, connecting with nature, finding animals, finding bugs, collecting butterflies, tadpoles, whatever. It was a lot of time on my own, drawing and just thinking and creating and a lot of time with other kids organizing and doing fun collective projects.

The one in the neighborhood that always said, “Hey guys, let’s build a fort.” “Hey guys, let’s build a go-kart.” “Hey guys, let’s make an airplane out of wood and hang it from a tree and fly”—which we did until the rope broke and it crashed.

But so there was an alpha social component, which is now critical, but there was also a quiet creative and introspective component to it. And I think it was—if I look at my life now, it’s my comfort in both of those zones that allows me to do what I do. Because a lot of people are good writers, are good creators, good artists, but they don’t have the social organizational component to motivate people to do things and to leverage their creativity. And so that’s a big part of it, that sort of alpha component, if you will.

From Truck Driver to Filmmaker

JAY SHETTY: Yeah, absolutely. It’s fascinating because you hear about this passion in your childhood, the flow to draw and create and to be fascinated with nature, and it almost makes sense. But then you become a truck driver. And so walk me through that arc of your life, because I feel so many people kind of up until ten, eleven years old, may even have these passions and dreams and ideas and creatives, but then their life takes a different turn.

JAMES CAMERON: I never went to university, per se. I went to the Fullerton Junior College, which is part of the junior college system. I was intensely curious. It was the first time in my life where I was surrounded by people who actually wanted to be there, as opposed to high school, where people didn’t want to be there, they just had to be there, and most of them sort of rejected the learning process.

I was always hungry to learn. Not necessarily what they were teaching, but lots of new things. I got to college and I was surrounded by people who actually wanted to be there and wanted to learn. And people were having arguments about philosophy and English and storytelling and art. And it was very exciting, but it was unsustainable for me. I couldn’t afford to do it continuously or endlessly. And so I had to work.

And I worked various jobs, all blue collar jobs. And I didn’t mind working. I didn’t mind just sort of being—and I got married at a very early age. I had a little pink house with a white picket fence and a dog, and it was kind of comforting. It was very, very limited and simple, but at the same time, as a truck driver, because it was a nine to five or an eight to five job, I was painting, I was drawing, I was storytelling for myself.

My wife didn’t understand that. She was a waitress and she liked the me that was social and with her, but not the me that was off creating all these worlds. And so I was still trying to reconcile that kind of social facing versus the landscape of my own imagination.

But I’ve always been comfortable in my own head that way. Dreams are a big part of it. Dreams are a big part of my creativity and sort of imagery source, of little bits and pieces of narrative, because it could be quite chaotic and jumbled, but still within that there could be some interesting ideas.

And so I think it was all just building up, building up a pressure to the point where I had to do something about it. And that was in my mid-twenties. And so I was kind of a late starter. I never went to film school. My film school was the drive-in movie theaters of Orange County. So no formal training in film aesthetics or film history or any of that stuff, but it was just kind of building up that—all right, it’s that urge to—when you can’t not draw, when you start thinking filmically and in terms of storytelling, it’s like, well, you can’t not tell a story. You’ve got to tell somebody the damn story.

And I think anybody out there that hears this, that feels that way, you’re stuck. You don’t have a choice. You’re probably going to be a filmmaker or a writer or whatever it is. Just accept it. You might never be rich because it’s a difficult task and there’s a lot of luck, I think, involved in getting to be a successful storyteller. But I just followed and I didn’t question it.

I just quit my job one day. No rancor, just “Guys, I got stuff to do. I’ll see you” to my other—the other drivers. And they’re like, “What? Where are you going?”

Taking the Leap Without a Safety Net

JAY SHETTY: It feels like a bold step, looking back, because without film school, without having made a film, without any of that background to watch Star Wars, I believe in 1977, and for you to then go, “I need to go and become a filmmaker,” even though you love drawing—and it feels like a bold step.

And I think about all of our listeners in our community who are all thinking something similar. I think a lot of people in my generation and the generations after me maybe studied something at school that wasn’t the thing they wanted to be. They have a dream inside of them. They have a story and they feel a pull, but they’re scared to take that final step. What gave you that conviction? Was it conviction or what was it?

The Creative Process and Early Breakthroughs

JAMES CAMERON: I think it was a conviction. Star Wars helped. And I’ve talked to George Lucas about this. I said, “There are untold people that you’ve inspired, George, but I’m one of them.” But in a way, I don’t think he quite wanted the answer that I gave, which was I was already seeing all that stuff in my head.

And when I saw Star Wars, I thought, if that could be the highest grossing film in history, then the stuff that I’m seeing in my mind when I listen to fast electronic music and imagine space battles and all this crazy stuff, it’s like, I should be doing that. There will be a market for it. There’s a market for my imagination.

And that’s maybe the boldest step, is the step you take internally, where you give yourself permission to at least go try it. And when you make that commitment, you have to go in wholeheartedly. You can’t say, “Okay, I’m going to be a filmmaker part time, but I’m going to sort of keep a foot in like medical school.” It’s not going to work. You’ve got to go. You just got to jump out of the plane and hope you’re wearing a parachute.

So I always, opportunities come along and they’re fleeting, and that door will open for a moment and then it’ll slide closed. And you’ve got to be, fortune favors the prepared mind. If it’s really something you love, read as much as you can. Prepare your mind ahead of time. Be ready. Because when that door opens, the critical thing is to understand it’s not an example of an opportunity. It is the opportunity. You either take it or you don’t.

You don’t use it as a time to think about, “Well, when the next one comes along, I may or may not.” That’s not how it works. You go, you launch.

And that opportunity for me was that a guy that I was working with on learning to sculpt and make molds, who was a little bit ahead of me on the sort of fan curve of actually knowing how to do rubber armatures for stop motion, and I was pretty fascinated by that. His sister was dating a guy who was a carpenter on a super low budget Roger Corman science fiction film. And I just said, “Introduce us.”

And so she talked to him, he talked to them. We got an appointment, and we went in and showed our little models and our little things that we had. And I had this film that I had made with some friends, and we both got jobs on a Roger Corman film. And we thought we’d died and gone to heaven because now we were getting a paycheck on a real movie.

No, it was a total piece of crap movie. It was a little tiny movie. It’s actually the biggest movie Roger Corman had ever made. It was like one million dollars or something like that, which was huge for him. He usually made movies for like $200,000. But all of a sudden, I’m on a movie and then the rest just sort of made sense after that.

It’s that prepared mind thing. I had read everything I could possibly read. I had schooled myself on how visual effects were done. All for no money, all not at university. Just over the two or three years that I was driving trucks and working blue collar. So I guess in the back of my mind, I must have thought, “I’m going to do this for real at some point,” because I was clearly preparing myself, but I had no entree.

I didn’t know anybody that knew anybody that knew anybody that worked on a film, even though I was in Orange County. It’s not that far from here, not that far from the center of the film industry, but it might as well have been Montana at that time.

Dreams and the Creative Mind

JAY SHETTY: Do you record your dreams? How do you note them down? How do you capture them?

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah, sometimes I’ll wake up and I’ll just write it down, or I’ll type it out on my laptop, whatever.

JAY SHETTY: How long have you recorded them for? When did you start?

JAMES CAMERON: It’s sporadic. I mean, it’s a constant sort of streaming channel that’s running all the time. And they’re not all necessarily worthy of, but every once in a while I’ll get a corker. It’s like, “Oh, man, I’ve got to write this one down. You won’t believe this.”

JAY SHETTY: Did you ever follow the curiosity of where they come from or how they originate? Where do you think you get them from?

JAMES CAMERON: Look, I’ve read a lot on the theories of consciousness and dreams and what purpose they serve. And there are some researchers that think they have deep psychological meaning and others that think they’re really just the brain just kind of resetting itself and reshuffling memory and kind of cleaning house, and it doesn’t really have any meaning.

I happen to think that they have meaning to you. Now, my wife Suzy believes that she has, and I believe she’s right, has received premonitory dreams about events in her life. And she’s documented this in a way that I find quite compelling. I’m not 100% convinced. Sorry, baby, if you’re listening. Not 100% convinced, but she’s given me evidence that gives me pause.

And I’m a pretty hardcore empiricist. I’m not a mystic. I don’t follow all of the various winds, spirituality fads and things like that. That’s not how I roll. I’m very science oriented. You’ve got to show me. You’ve got to prove it. It’s got to be peer reviewed, and that sort of thing. It’s got to be the subject of double blind studies, and it’s got to be falsifiable and all the empirical stuff.

But I’ve seen some things I can’t explain. And she’s demonstrated some things to me that can’t be explained by my understanding of science. I mean, I’m not a scientist, but I did study physics, I studied astronomy, and I keep pretty current in the sciences. So there’s clearly stuff out there that’s not well explained or explained at all right now. Doesn’t mean it won’t be someday using empirical methodology.

I don’t know quite how I got off on that, but we were talking about dreams, and dreams are not well understood even by neuroscientists and so on. What is the brain doing? I personally think that we’re kind of, we’re like large language models. So all the training data of our life, it just goes into a kind of diffusion state, which is how generative AI works. It goes into a kind of a very noisy state. And then out of that coalesces new things.

And I think the brain is just constantly creating in the way that a generative AI works. But who’s creating it and who’s it being created for? So you’re simultaneously the creator and the watcher, which is kind of amazing. I’m creating a simulated experience for myself. One part of my brain is, and another part of my brain, let’s call it the ego locus or whatever, the person taking the ride, the kid in the roller coaster is going on the ride, which is kind of the filmmaking process.

That’s fascinating because I’m making a story. I’m making up a story for my kind of simulation of the audience mind, the group mind, right? So part of my brain is making up a story for another. That part of my brain is sitting in a movie theater with hundreds of other people and receiving it and judging it, like, “Okay, this is cool. I like that.”

The Writing Process

And you try to drill down on the creative process. I’m a writer, I’m sitting there, I’m looking at a blank screen. Where do you start? And a lot of writers do it in very different ways. Some start, page one, “Bob walks down the street,” and then it just goes from there in a linear fashion.

For me, it coalesces probably almost in a diffusion model kind of way. I start writing notes and little images come to me and I start putting the notes together. And for the Avatar sequels, for example, I wrote over a thousand pages of notes. Just little fragments, dreams and images. And sometimes dreams play a part in that. And sometimes just the daydreaming process, that creative engine, because I think that same creative engine that runs at night, out of control, non linear, chaotic montage style is actually more functional during the day and can be kind of directed to stay on a topic and follow it through.

So maybe I’ll be thinking about a character, and then something will pop into my mind, and then I’ll start writing about that. And it does, I’m not trying to tell a linear narrative at that point, and it becomes a bit of a dialogue.

So I remember the time I was sitting there in my writing office and I said, “Well, what if there was a kid that was born on the base, and what if he was out in the forest with his Na’vi little kid friends and his mask got messed up and they had to save him? He was running out of air.” And it became a whole thing. And so I imagined this whole thing about a race against time to get him back to the base.

And I thought, “Okay, that’s a pretty good story. Now, what if that kid was Quaritch’s son?” And then I wrote, literally wrote, “Nah, nobody would believe that.” And then I’m going on writing more notes, and about three or four pages later, it’s like, “Yeah, but wait a minute. It would be really cool.”

JAY SHETTY: Yeah.

JAMES CAMERON: And then I just started to riff on that and then it became, “All right, well, what if he was Quaritch’s son? And the human Quaritch dies in the first film? Now he’s orphaned. His mother maybe dies as well. She was part of the military group that Jake was opposed to. And now he’s an orphan and he’s being raised on Pandora and he’s got Na’vi friends. What if his Na’vi friends were Jake’s kids? What if? What if? What if? What if?”

Right? That’s how the writing process works. And then it just, and all of a sudden, ideas just, you can’t turn away from them.

JAY SHETTY: Do those creative ideas, do you find a set of systems or rituals or processes that help you access that, or is it more organic?

JAMES CAMERON: And I know every writer’s got their own process. Some, “I’m up at 5am, I run two miles, I have a cup of coffee, I sit down, I write 18 pages, and then I call it a day.” For me, it’s a slow boil. I noodle around for most of the day. I get to the point toward the end of the day, maybe four or five o’clock in the afternoon, where I’ve been playing, maybe I’ve been doing notes.

And then I’ll just say, “Okay, time to write some pages.” And then usually for about three hours, I’ll write pages and I’ll get four or five pages. It’ll come fast at that point. And that’s when you hit your stride in screenwriting.

JAY SHETTY: You can see that the way you’re describing this scene with Quaritch’s son because there’s almost like three different storylines kind of connecting in that moment around that one thing that you just pointed out.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah, yeah.

JAY SHETTY: But there’s so many other things going on at the same time.

JAMES CAMERON: Oh, I usually come up with way more ideas than I could conceivably pack into a movie. And then I’ll winnow that down. I’ll winnow that down to a big old fat screenplay that’s unshootable. And then I’ll winnow that down and then I’ll make a movie that’s four hours long. And then I’ll winnow that down.

And then what you get is the end result is the distillation of the best ideas. And then that’s what winds up in the lean, little tight indie film that I like to call Fire and Ash. Only three hours and seven minutes long.

JAY SHETTY: One thing I’ve been reflecting on lately is how even the smallest choices can create a big impact over time. Whether it’s choosing to spend a quiet night in to recharge, or making a decision that brings you closer to a long term goal, those moments of intention really matter.

What’s incredible about it, when I watched it, I was so grateful that you allowed me to go see it last week. And as I said when I was there, the gentleman in the theater who was playing it for me, he told me which seat you’d like me to watch it from, which I thought was a beautiful experience to have. I said, yes, I want to sit in the exact seat.

JAMES CAMERON: Well, no, it’s good that you moved back, though.

JAY SHETTY: I did. He told me I had that option.

JAMES CAMERON: I did that today, actually, for the first time. I watched from the seat behind. Now, normally that’s my working seat when I’m reviewing, because you could see that there’s a desk there with an Abbot and so on. But I thought, well, let me see. Let me see what it’s like from there, where it doesn’t fill my peripheral field and I’ve got a little bit more of that sense of control that you have when it’s a proscenium. And I thought, oh, this is actually pretty good.

JAY SHETTY: It was spectacular. But more importantly, three hours and seven minutes flew by. There was never a moment I didn’t, I was, I didn’t look at my phone once in three hours and seven minutes. To me, that’s the test today of having your engagement, attention and awareness.

JAMES CAMERON: Right. So we passed the most critical test.

JAY SHETTY: Yeah. And the most magnificent thing is that so much happens.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah.

JAY SHETTY: You’re just on the edge of your seat wondering what’s going to happen next. And so much is happening. And to do that for three hours and seven minutes in your movie is pretty, it’s just an incredible feast for the eyes and ears. I felt like all my senses are engaged all the time, which is such a beautiful experience to have where just every time a new scene opens, you’re just totally captivated.

JAMES CAMERON: Well, thanks.

JAY SHETTY: It’s so hard to do that for that long, especially with, I consider myself to have good presence and attention. But even then I can turn off something in 30 minutes. And so to have your engagement not just on a story level, but on a sensory level.

The Art of Sensory Storytelling

JAMES CAMERON: I think you’re onto something there. And describing as you’re saying it, I’m thinking, well, what are my goals creatively? I want to tell a great story with good characters that I care about, and I care about how they interact with each other and how their relationships evolve and how they resolve their own conflicts in a way that moves me. Because if I can’t move myself in a story, how do I expect to move an audience emotionally?

But then the layer on top of that is the sensory layer, which is color, composition, all of those artistic things. Because I also started as an artist, figuratively. But I could draw, I could paint. I knew the rules of composition. I learned all the art history, Renaissance lighting, composition, all that sort of thing.

So there’s an aesthetic level to it that I like. There’s the world building level, where every plant either looks real or has a purpose. And we spend an awful lot of time. Fortunately, we’re blessed with good budgets and good time to sort of let these ideas marinate and gestate. And I’ve got great designers. It doesn’t all flow from my consciousness. It comes out very out of focus, if you will. And it’s an act of working with other people to bring it more and more into finite detail.

I call it, my role is to create the grand provocation for the other creative people. And I got that term from my wife, Susie, who’s an educator, and she says that the school provides the provocation. The kids provide the investigation and the curiosity and the passion. And I think it’s the basis of her school. She can do all that stuff better than I can. I’m just a bystander to that part of it.

But I think about what I do. I come in and I said, guys, we’re going to do the coolest woven tropical village over water. What is that? You’d think that they could create that in a week or two weeks. No, it took a year. And because part of the provocation was, and it all has to be intentional, nothing is built with rigid cut lumber the way we would do it, where we create posts that are in compression. Everything’s in tension. It’s like a spider web. It’s all woven between these big structures like the mangrove roots.

And so they were actually sculpting with pantyhose to get the right degree of elasticity, to put it all in tension. They sculpted the village with pantyhose. This is absolutely true. And then they wove these little structures that later became the homes and the walkways and all of that. And then they developed it from there. And then eventually we started building full scale, not full scale, but say, quarter scale models of these woven structures.

So when you walk through it, you don’t really get a chance. I always want to give a little more than you can fully perceive, because isn’t that what daily life is like? There’s always more going by than you can fully perceive. And so the brain becomes selective. Okay, what’s narratively important to me in the moment?

Universal Stories Through Alien Worlds

JAY SHETTY: My wife always says, I think James Cameron and his team have been to other planets. That’s what she always says whenever she watches one of your movies. She’s like, he’s been to other planets in other lifetimes. She’ll be like, how is it that you could, and you feel that because you feel the depth of the relationship the characters have for each other. You feel that you fully believe this is real. It must exist somewhere.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah, right.

JAY SHETTY: Because how can you feel so deeply for people who look different to you and feel different to you and have different experience?

JAMES CAMERON: But we feel that’s a goal, right? So the goal is, all right, these people look different, they’re physiologically different, they live in a different place. But doesn’t that give us permission to step outside ourselves with our petty little differences between race and culture and religion and politics and all that stuff?

Step well outside ourselves and see kind of universals of human behavior and the things we care about, whether that’s a sense of duty and love that a parent has for their child. And that’s why these films travel, I think, why they resonate in China and India, in Europe, in Africa, wherever they go. Because I’m trying to deal with universal stuff, but I’m not trying to make stuff up.

So with the sequels, Way of Water and Fire and Ash and beyond that, if we get to make some more, I don’t know if we will or not. We have to make some money. I mean, it’s a business also. But if we do get to make some more, the stories are about a family. And so I couldn’t probably, not only couldn’t, but probably wouldn’t have even tried to write them if I hadn’t been in a large family and gone through all that teen angst and that issue, the father issues and not being seen and all those things, and then having been a father of teens.

Susie and I have five kids. And so, I mean, artists are just working out their stuff, their lived experience and project. But taking that to another world and putting it in another context allows everybody to share in it or recognize themselves in it, either in an aspirational way, like, wow, I wish I was part of a family like that. My family, not so great. Or maybe I don’t have a lot of siblings, or maybe I wonder what that would be like. Or maybe it’s like I’m in exactly that kind of family.

JAY SHETTY: Yeah.

JAMES CAMERON: And I wish I wasn’t sometimes.

JAY SHETTY: I’ve been repeating to my wife, I’m saying this in reaction in response to what you just said. Now, I’ve been saying to my wife all week, we need to have, we don’t have kids yet, but we plan on having them one day. And I said, when we have kids, we need to have mantras and affirmations as a family. So I keep saying to, “Sully’s never quit.”

JAMES CAMERON: There you go.

JAY SHETTY: I keep saying that. I’m like, I love that statement. It stuck with me. And I was like, to see the little child’s courage in that moment, right, where they’re in so much danger and so much pain, but they remember that their dad told them that “Sully’s never quit,” right?

JAMES CAMERON: And then when she says it, when she says it later, she basically saves the world with one thing where she says, come on, we can do this. Sully’s never quit. And you’re like, go, Duke.

JAY SHETTY: Yeah, exactly. And that’s that feeling of, I’m like, to see that courage in a young person and how these simple universal messages are things they hold on to in a child’s mind.

And then even the storyline with Payakan, for me, that, oh my, I mean, from the second to the third, because when I watched the second movie, for me, that fully just made me fall in love with sea life in a way that I hadn’t before. And I was like, wow, this is genius in how you’re sharing a message around water wildlife that we just don’t treat well anymore.

The Intelligence of Whales

JAMES CAMERON: We won’t protect what we don’t love and care about. Right. And so I’m working on a very small part of a much bigger project that’s being run by a marine biologist named David Gruber. And he’s working with people who are in AI and machine learning, more on the learning side of AI. But they’re using some large language model technology as well to decode whale vocalizations.

So they’ve got thousands of hours of sperm whale vocalizations and they’ve got some context footage of what socially they’re doing. And they’re decoding their clicks, which are called codas, and their click sequences, and they’re finding that they have verbs, they have syntax, they have complex language, at least as complex as human language, which is kind of amazing.

But it all sounds like, if you could actually hear it, it sounds like that’s a whole paragraph in sperm whale. And it’s taken years and years and AI tools. So, yeah, nature is far more complex than we understand.

Consciousness is clearly shared by some of the higher mammals, even some birds that have true consciousness. That they recognize themselves in a mirror and that’s one sign that there is a higher form of consciousness. A dog doesn’t recognize itself as an individual in a mirror. And we think of dogs as conscious, and of course they are, and they’re emotive and they’re empathetic and they’re very much like us emotionally, but they don’t have a consciousness high enough to recognize their individual selves in a mirror.

But an elephant can, a chimpanzee can, and a dolphin can. And I don’t know if they’ve done that. I think they’ve proven that a beluga whale can as well, but I don’t think they’ve done it with, it’s just a little difficult to do because you can’t put them in a tank and study them like some of the smaller toothed whales, like dolphins and belugas.

But anyway, there’s even a parrot species in New Zealand that is intelligent enough to recognize itself as an individual. Most birds can’t. So you’ve got these glimmers of emergent consciousness besides us. And now we’re going to have machine consciousness emerging in the next decade or whatever it’s going to be. And that’s going to be a whole new set of challenges for us as well.

We don’t even understand consciousness yet in ourselves. And now we’re going to have to start relating to this alien consciousness that we create.

JAY SHETTY: Yeah, absolutely. And it’s almost like I was speaking at a conference about AI and consciousness recently and someone asked me if I ever believed AI would ever have a soul. And my response was, I’m not qualified to answer whether AI will ever have a soul, but I really hope the people building AI have a soul because it’s so much of.

JAMES CAMERON: Bingo. Or conscience.

JAY SHETTY: Yeah, more conscious, what I meant. Yeah.

The Nature of Consciousness and Soul

JAMES CAMERON: I think you can have, if you believe in some kind of animus or spirit or soul or whatever it is that’s persistent beyond the biological framework. I personally don’t, just saying that up front, but I also won’t bet completely against something that just hasn’t simply been proven yet.

But I also only believe in believing in things that have been empirically demonstrated and being kind of agnostic or fluid about everything else. Right. But if you do believe in that, then a machine couldn’t possibly have that now, could it? Because we didn’t create that in the first place. And if we think we can create a machine that can have it, then we can’t. So now you get the sort of the soulless Frankenstein kind of mythology around that.

On the other hand, if you believe that consciousness is this kind of field of operations that is almost infinitely complex, but can be understood as a real world thing based in matter, then theoretically a machine intelligence could be as soulful, as empathetic, as emotional as us, although it might be very, very, very different.

And then you get into the quantum physics of consciousness where you’ve got observer effect and things like that, where there seems to be some link at a quantum level with consciousness, and then all bets are off, you know. And I’ve had some strange experiences with one practitioner in particular that believed in quantum consciousness and could do things I can’t explain to me, to my mind.

JAY SHETTY: What do you mean?

JAMES CAMERON: Well, could actually create a state of consciousness in my mind by sitting across from me, just like you are right now. And I am not, I’m not hypnotizable. Nobody’s ever been able to hypnotize me. I’m pretty resistant to any kind of suggestibility. But this particular individual was able to do something.

JAY SHETTY: What were you experimenting with that you even sat across someone like that?

JAMES CAMERON: My wife Susie had met this guy and worked with him, workshopped with him a lot many, many years earlier and said, “You really need to meet this guy.” His name was Carl Wolf. And I was very skeptical. Like I said, I’m an empiricist. You’ve got to, you know. And I said, all right, I’m skeptical, but I’ll do it for you, baby.

And something happened, and I can’t explain it. Something happened. Now what was it? I don’t know. Carl had hypotheses. I don’t know if his own hypotheses were accurate. I’d love to ask him, but unfortunately he died tragically in a car accident. And because I wanted to, like, can I just spend millions of dollars studying your mind, please?

JAY SHETTY: That’s fascinating. I mean, what’s beautiful about all these worlds you create, and when I was researching your story and learning about just how many failures and moments you’ve had to quit and give up. And again, I think about our listeners and I think about them.

JAMES CAMERON: He’s never quit. Sally’s never quit. There you go.

JAY SHETTY: And even what you just mentioned right now about your own experience with your father and then becoming a father and what that looks like. Are the worlds you create, worlds that you didn’t have or did have for you?

Creating Emotional Journeys Through Film

JAMES CAMERON: I think both right thing. I mean, the thing that I’ve tried to do in the Avatar films is create a dynamic range of experience from ecstatic to terrifying to heart wrenching, from despair to joy. All of those things.

I think movies are pretty good at creating a state, maybe a state of dread or something like that, but I don’t think they’re good at taking you on that roller coaster ride that more is the way our real existence is. So I wanted to have amazing moments of beauty. I think beauty gets forgotten in movies these days. You know, everything is about threat and conflict and all that.

But I also wanted to take you on an emotional journey where you get to places that are either terrifying or heart wrenching through loss or whatever. And that’s all dependent on performance, you know, that’s all dependent on the actors. The actors are our path through this, our conduit. We see it all through their eyes, you know.

So for me, act of creation, everybody is quite enamored of the world building because that’s what they see. They see the end result. But for me, it’s about getting those characters down on the page, bringing it in with my actors.

And the beauty of the two sequels is that I was writing for actors I knew and I could hear the way they’d say it and I didn’t feel the dialogue was right until I knew that Stephen Lang, who plays Quaritch, would say it that way, you know, or Sam would say it that way or Zoe would say it that way.

And then of course I threw a new element in, which is Una Chaplin, who plays Varang, who is, you know, pretty terrifying character at times. And I was making her up out of whole cloth. Obviously I didn’t know who the actor was that was going to play her.

But that’s the part where I think that engagement that you were talking about, it’s not just sensory and visual, it’s also so heartfelt. Right? And we bring our own human experience to it every time we walk into a movie theater.

The Magic of the Theatrical Experience

And I also think a critical part of the engagement is the theatrical experience. So a lot was made, you know, during the rise of like DVD and Blu-ray and all that. A lot was made about the fact, oh well, you don’t have a screen that big, your sound isn’t that good. The theater is a better experience.

But we’re at the point now where your home TV set and your home sound bar and everything is as good as what you’re going to see in a movie theater. So that goes away. So what’s left?

What’s left is in our day to day life, we’re very fragmented and scattered and distracted and multitasking and we’re scrolling and we’re typing and we’re connected and multi-channeling all simultaneously. Very rarely do we just sit in a meditative state and just focus.

You know, people who practice mindfulness and yoga and things like that, they know how to do that and they do it to clear their mind. But how often do we do it where we focus on a received experience? You know, some people will sit and read a novel for hours and hours. I think they’re a dying breed, unfortunately.

But the movie theater is one of the last bastions of a focused entertainment where we make a deal with ourselves. Before we go there, before we leave our homes, we make a deal with ourselves that for two or three hours we’re going to be undistracted.

And then all of a sudden it’s like the world goes away and you’re on that journey and nothing else matters for that brief period of time. And I think that’s the real magic of the theatrical experience. And it boils down to one simple thing. You don’t have a remote. It’s that simple.

You can’t pause it. You can’t go order a pizza. You can’t pause it, go to the bathroom. You can’t be in a room with other family members who are talking and you pause it so you can hear the lame comment.

JAY SHETTY: Absolutely.

JAMES CAMERON: I’m kidding. No, kids don’t make lame comments. But they do comment during the movie and I pause it and I’m like, yes, you were saying?

JAY SHETTY: That’s so funny. Do the kids ever look at the movies and go, “Dad, you just made a character out of me.” Like, is there any of that?

JAMES CAMERON: I think they see that there was a moment in time 10 years ago where who I believed they were influenced the creation of a character. But I think for them it’s all a big laugh.

JAY SHETTY: Yeah.

JAMES CAMERON: Because they say two things. One is, that was 10 years ago. And two, even then you didn’t really know who I was.

JAY SHETTY: That’s really, I want to come back to depth of character. But I wanted to talk about failure because you’ve told this story before. But the part I wanted to ask about was before you made Terminator, you actually lost a job.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah.

JAY SHETTY: And we won’t mention the film because I heard you didn’t mention it. But like, for anyone who’s finally found their way, you went from truck driver, starting to make films, made this small movie, you get fired off a job.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah.

JAY SHETTY: That almost feels like, all right, well, this is the end of the road.

JAMES CAMERON: You.

JAY SHETTY: You said you f*ed up that way.

Turning Failure Into Opportunity

JAMES CAMERON: It felt that way. And it felt like there was, going into my first directing gig that I did get fired off of after, I think, six or seven days of shooting. And not for incompetence, it turns out. It turns out that I was being set up the whole time. And when I found that out later, it sort of put it in perspective.

But I believed at the time, I internalized, that I was not doing it well, you know. And I thought, oh, crap, now I’m worse off than if I hadn’t taken the job in the first place. Now I’m at negative 10. I could have just been at zero. Now I have to dig out of a hole to get to zero. Yeah. You know.

And so then I knew I had to do something extraordinary or something different. I couldn’t wait for a directing gig to come to me. I had to create it for myself. And that’s when I wrote the Terminator.

I thought, I have to write something original, something that I could plausibly make that wouldn’t have an enormous budget. And it was scaled to, you know, conventional locations, present day city streets, that sort of thing, so that we could do it relatively cheaply.

But I also thought, all right, but I’ve got to inject into it. It can’t just be, you know, a simple drama. I’ve got to inject into it something that I bring my expertise. So my expertise was in design and in visual effects.

I thought, all right, so I’ve got to create a careful balance here. The visual effects have to be very limited, but they have to be powerful so that they’re, so that it’s not a ridiculous budget like a Star Wars movie that I knew we couldn’t afford or nobody would hire me.

So then I came up with the idea of a futuristic technology that gets injected into the present day. Time travel. Right. So there was a logic to the story elements that I was playing with that was based entirely on being practical and trying to get a gig.

So would I have come up with that story if I didn’t have those constraints? I don’t know. Maybe not, you know, but it all worked out. So I thought, all right, I want this extraordinary thing that requires, you know, animation and design, this Terminator. But I’ll have it come from the future, which I don’t have to see, and I’ll just see present day. You know, we could just use available light, street lighting and that sort of thing, which is kind of how we did it.

JAY SHETTY: That’s such a fascinating point you just made, though, that constraints actually led to brilliant creativity. It wasn’t the other way around. And often we get lost in the trap of, “When I have resources, I’ll make a masterpiece.” And you made something that’s timeless.

The Challenge of Infinite Choice

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah, that’s really good. I mean, you know, the resources will come eventually. And that brings its own curse, because now you can do anything. And when you have infinite choice, you could get paralyzed. Right?

And an Avatar movie is an exercise in limiting choice, because when you work with performance capture, I get a great performance, but then I can put the camera anywhere I want. I could cut it anywhere I want. I’m not constrained by just the footage that we were able to grab that day before the sun, sunset. It becomes a kind of a problem of infinite choice.

I think it makes you a better filmmaker. Because now, why is the camera going right here? Not because that’s the farthest back I can move before my ass hits the wall, and that’s the widest shot I can do. Why is it here and not back there or not over there? You know? And so it forces you to become quite rigorous about your aesthetic.

You know, that’s a separate problem from getting great performance, by the way. And the weird thing about an Avatar movie, it’s a little weird, is we separate performance from cinematography. We do all the cinematography later. I don’t even think about it. I don’t think about the camera angles.

When I’m working with the actors, I know I’ll be able to shoot it. I don’t know exactly how I’ll shoot it, but I’m just, I just care about the heart and soul and the authenticity of the moment with the actors. Now I’m done with them. Now they’re all working on another movie.

Now it’s like, okay, am I on a wide shot, close shot? Am I on a long lens, short lens? Is the camera moving? Is it still? Is it raining? Is it not, you know, is it night? Is it day? You can make all those decisions later with that nucleus, that sort of beating heart of the performance. But you can interpret it many, many different ways so that that idea of, you know, infinite choice, it can be paralyzing or it can make you more rigorous.

And it forces you to define to yourself and to the others you’re working with, other editors, other designers, why you’re doing it that way. And sometimes I just, I just talk. It’s like, okay, you know, it’s like, I’ll talk while I’m working. It’s like, okay, I can be here, I can be there. I can put the camera here. What do you guys think? You know? And they’re like, well, I like the water shot. It’s like, okay, let’s do the water shot. It gets more inclusive in a way. Not that I’m doubting myself, but it’s like, why not? Why wouldn’t you be inclusive?

The Dollar Deal That Changed Everything

JAY SHETTY: Yeah, absolutely. And you assume, committed to that, that you sold it for $1 and rejected all of these amazing studio budgets because they wouldn’t let you direct it.

JAMES CAMERON: This is going back to the Terminator. You’re talking about the fact that I made a rights deal with Gale Anne Hurd, who was another up and comer in the same super low tier as I was. And she had the eye of the tiger. And I recognized in her the same thing she recognized in me, which is that we could, we could get this done. We could make something happen together.

And so I sold her the rights for a dollar in exchange for a promise. And that promise was worth a lot more than a dollar to me, which was, “You will never proceed with this movie.” I mean, I could have written a 20 page contract to do it, but it was like a blood oath, almost literally. I don’t think we actually cut our hands, but it was pretty much that.

And this is before we were romantically involved. This was just us, you know, a nascent producer and a nascent director. I said, “You will never make this movie without me as a director, and I will never make this movie without you as the producer.”

And, man, they tried to split that team. They tried to get her in the rights and, and not, and get another director, you know, and there were times when, when Gail was beating them up so much on the budget, they took me aside and said, “Look, we’ll make the movie with you, but we got to get rid of her.” And I’m like, “Nope, that ain’t going to happen.” And she said, “Nope, that ain’t going to happen.”

So in a way, everything else flowed from that. And so that was, you know, that was a dollar well spent.

JAY SHETTY: Yeah, that’s, that’s, I love that story. It just, every time I hear you tell it, from when I was doing research and listening to you tell it and even hearing it now, I’m just like, there’s such a, today there’s such a fixation on getting what you deserve.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah.

JAY SHETTY: And demanding what you deserve. And I think sometimes it sets you up for failure because you could be waiting a long time for someone to give you what you deserve.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah.

JAY SHETTY: And your career is this constant, constant. Well, I’ll build what I deserve or I’ll, I’ll take it myself.

You Don’t Deserve Anything

JAMES CAMERON: The simple answer is, you don’t deserve anything. It’s just a question of what you can negotiate for yourself and what you can prove, prove to the world, you know, that you’re, you’re capable of. Right. And then, and then, then the money will flow from that and the, you know, all of those things will flow from that.

I never was in it for the money. In a sense. I’m still not. You know, it’s a consequence of doing the job well and reaching people and communities, communicating. You know, I am a commercial filmmaker. I don’t try to do something that’s intentionally obscure or intentionally so kind of intellectual that, you know, that it doesn’t connect for the majority of the audience.

I’m a bell curve guy. You know, it’s like I want to, I want to hit that sweet spot in the middle of the bell curve where the, where I’m communicating with the greatest number of people. And there will be some people for whom it is, it is beneath them to even consider enjoying an Avatar movie. And there are some people that just don’t get, get it on the, on the other end, you know what I mean?

But I’m looking at that bell curve, and I think there are some filmmakers that, that want to indicate that they’re smarter than the audience and challenge them to try to keep up and pirouette their intelligence. Not to say they’re not intelligent, but come on, guys, it’s entertainment. It can have deeper meaning.

I mean, I like to have thematic layering, you know, and I like to have things that mean something to me, and if people pick up on it, great. But I won’t make the story hinge on that, you know. So I don’t know, maybe it’s that drive in movie, you know, college of Cinematic knowledge, that, the drive in movie theaters of Orange County paying off.

The Biggest Risk Is Not Taking Risks

JAY SHETTY: I feel like everyone looks at you and even these examples you’re talking about, there’s such a, people would say, you know, James Cameron’s a risk taker, he takes big risks.

JAMES CAMERON: And.

JAY SHETTY: But do you see yourself that way? How do you, I feel like it’s something more than that.

JAMES CAMERON: Well, I think, I think it’s not a question of taking a risk for risk’s sake, but I do think the biggest risk as an artist is to not take risks because then you’re just doing what you’ve done and what, you know, and, and, or what other people have done, which is even worse, you know, just in being in a, in a kind of a comfort zone of mediocrity.

So, yeah, I think, I think you do take risks, but having taken that risk, you then do everything within your power to make sure that you are communicating that it is working, that you’re not jeopardizing large amounts of other people’s money by doing something foolish.

You know, Titanic was a risk. You know, it was a very, very expensive film in which basically everybody dies, you know, and it was a period piece and it was three hours long. The only successful film previously that had been three hours long, that was a commercial film, was a Best Picture winner, which was Dances With Wolves. I always pronounce it Dances with Wolves because it was a name, you know. So, yeah, I always imagine it hyphenated. Not Dances with Wolves. Yeah, which is what most people say, but I don’t know if that’s accurate. And, you know, I never asked anybody, but probably is, but.

And so we were in uncharted territory. I mean, we went in knowing it was going to be a long film and that it’s a tragic film and that it’s a tragic love story. Pretty risky in a sense. You know, it certainly didn’t follow any of the commercial paradigms of the time.

And we reached a point after we went over budget, even though the film was looking pretty good in the dailies and in the rough cuts, we reached a point where the studio was utterly convinced it was only a question of whether they were going to lose $50 million or $150 million. And they were so dead set on an outcome, they almost manifested the outcome they dreaded because of their lack of faith in the film.

I even almost, in a way, lost faith in the film being commercial, but I never lost faith in it being artistically correct. And that’s when I, it’s, the story’s been told, but it’s actually true. I literally had a razor blade taped to my Avid screen with a little sign that said, “Use in case film sucks.”

Because I knew that the only way out of this was through, and the only way through was to make the best possible movie you could make. Even if I didn’t make a dime off it, even if it failed commercially, it had to be good and it had to deliver on, on those artistic principles that we went in with. I knew I had a great cast, I had great performances, you know.

And it turned out from, from the moment James Horner played the first, he had, he wrote three themes and just reiterated them throughout the score. He wrote three themes and he played them for me on his piano in March of 1997. And that’s when I knew I had a movie because I cried on all three themes.

First one was just like, “Holy, dude, it’s amazing,” you know. And I said, “We’ve got a story.” He said, “I haven’t written the score yet.” I said, “We’ve got a score.” And I wasn’t wrong. I knew from that moment that it was going to be great.

And yeah, sure, he, he, he wrote it, he orchestrated it, he went out, he recorded it with 100 piece orchestra. But I knew from that simple piano melody that was, we were good. And, and I think at that point I started to have some faith that the movie itself would deliver on what I intended it to deliver. You know, there’s a funny point in movies, it’s okay if I just kind of.

JAY SHETTY: I love it. Please. That’s my favorite bit of podcast.

When the Movie Isn’t Yours Anymore

JAMES CAMERON: Okay, please. There’s a certain point in making a movie where it’s not your movie anymore. I think it’s my movie when I write it. I think the second I cast it, it’s not my movie anymore. And the second I’m working with designers and we’re building sets and all that now, it’s got its own, own momentum, it’s got its own life.

And there’s a point in post production where it’s being received. And I don’t mean that necessarily in a mystical way, although it might be, I don’t know, but it’s being received from the group’s creative energy. What the actors did, what the designers did, what the camera operator did, you know, what the DP did.

And it’s just up to me to see it and see it in my emerging and then help assist, you know, clear, clear the debris out of the way, get it to kind of emerge. And, and I felt that more so, especially on these last two Avatar films that I’ve ever felt before.

We got a long film. It’s half an hour longer than it could be. You’ve got to take stuff out, so you’re pairing away and, and themes are emerging and getting stronger. And it even got quite snaky on this last one because I felt the themes emerging so strongly that I actually wrote new scenes and asked the actors to come back and reshape the whole thing.

For example, there was a scene in the script which we captured where Jake teaches all the Navi how to fire machine guns. I was wrong. I didn’t want, that’s not what the movie was supposed to be saying. And so the power, the dark, grim power that comes from when Quaritch arms the Ash people and you see them lift those weapons up and you say, “Oh, my God, this whole thing’s going, going wrong.”

I can’t have Jake be doing the same thing. But I somehow I didn’t see that in the writing, but I saw it as it was unveiling itself to me. And I called everybody back in, I said, “Guys, you got to come back.” And the beauty of performance capture is you can recreate the set almost instantly in like an hour.

So we just were able to go back into it. And I did something else instead, which is I had Jake go get the Toruk, which was also not in the script. Ah. But when you see, you think, how could that, how could that not.

JAY SHETTY: That’s one of the most epic moments of the whole.

The Weight of Sacrifice and Duty

JAMES CAMERON: Exactly. Well, I had put that in Movie four, but I realized I was playing too long a game. You know, you know the scene with him and Spider, which I won’t go into the details of, but after that, you know, when Nati says, “then we will find another way,” that’s the only way he’s got left is to do the thing that he dreads the most.

JAY SHETTY: Yes, yes.

JAMES CAMERON: That he absolutely knows will take something out of his soul. But he has to do it. That’s the only other way. And so sacrifice is a theme that I deal with a lot. Duty. Because you can’t have love without the fear of death, the fear of loss, without the need for sacrifice, without a sense of duty.

What will you do to prove yourself in a loving relationship? Played with that on Titanic. Played with that on Aliens. Played with that on Terminator 2. Right. And so these last two Avatar films are the same thing. What would Jake and Neytiri do for their children? What would they do for their people? And what happens when what is right for the children is not right for the people?

If the right thing is to go to war… And I know that you’re all about peace and purpose and all of that, and I agree with all of those things because I think empathy is our great human superpower which will get us through this somehow. But I do believe there are times when you do have to fight. I’m not a total pacifist.

And I think in my lifetime there has not been a righteous war that the U.S. has been involved in. But World War II, when you have a predator that’s destroying everything that is of value to people. Yeah, you have to fight. You have to fight for your survival. So we could have a whole conversation just about this.

JAY SHETTY: I know, I was just about to say that the… Well, I was about to say that.

JAMES CAMERON: I’m flipping the scripture.

JAY SHETTY: I love it. No, I was about to say that the spiritual text that I practice and teach and follow is based on a battlefield and it’s God or the divine telling the greatest archer of his time to pick up his bow and fight for righteousness and duty.

JAMES CAMERON: For righteousness and duty.

JAY SHETTY: It makes a lot of… It definitely resonates what you’re saying, saying that, yeah, there is a need.

Righteous Violence and the Tulkun’s Choice

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah. So I’m an action filmmaker, so I’m, you know, action. I mean, if you think about it, action is just a candy coated term for violence. Right. When it’s righteous violence practiced by the good guy in defense of good people and so on, you know, we spend a lot of time justifying it to ourselves.

And I think a lot of the classic cinematic justifications aren’t really sufficient. Which is why I went down the road of having the Tulkun be utter pacifists, where they have rejected any kind of violent confrontation up to and almost including their own final destruction. But they, at the very brink, they decide that there is something that they have to rise up for.

And when they see the horror of what’s happened to Tan Oak and Payakan’s clan and all that, which I think is quite a heart wrenching scene.

JAY SHETTY: Even though that’s… Right, yeah. When you make me feel for Payakan, I’m… that’s… you know, because now you’re not even feeling for something that looks remotely human.

JAMES CAMERON: Right, Exactly. But we’re able to see consciousness in others, in the eyes, you know, in dogs and in the great apes. You know, I think it’s a little harder in birds, even though they’re pretty damn smart.

Whales, though, have a soulfulness and maybe, maybe to some extent we projected onto them. But I don’t think so. There’s something very calm about whales. You know, they’ve been greatly injured on our planet. So I think, you know, what I was trying to express there is, look what we’ve done to them. And they don’t seem to hate us as much as we would if that was done to us.

Although there are pods of orcas near Gibraltar and off the Azores that are attacking sailboats now and ripping the rudders off and leaving them adrift. So it’s… are they learning? Are they learning that we’re actually not so great for them? Yeah. Orcas have a matriarchal society and the mothers teach the sons behaviors.

And so the question is, is this being handed down? Because it’s been happening a lot in the last few years. And it’s the same group, the territorial group.

JAY SHETTY: All of this you’re talking about. You spent around 10 years just studying the ocean. Right. While you weren’t making films at that time, you literally went deep into literally everything that you’re sharing right now.

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah.

JAY SHETTY: While you weren’t making films at that time, you literally went deep into literally everything that you’re sharing right now.

JAMES CAMERON: I went as deep as you can go.

JAY SHETTY: Mind blown. Did you just put everything else away?

A Decade in the Deep: Leaving Hollywood Behind

JAMES CAMERON: Not really. I kind of kept my hand in. So after Titanic was a big hit and I was questioning, you know, is this even important? Is Hollywood even important? It seems like such a glitzy game and it seems kind of quite fatuous.

And at about that time, I wound up on the NASA council, believe it or not. And I looked around a room full of people who were very intelligent, most of them, all of them really better educated than me, with a strong sense of purpose. Right. That they were doing something extraordinary. They were exploring space and none of them cared about Hollywood.

They didn’t even know what was happening. “Oh, the Oscars, what’s that? Oh, yeah, you know, it’s where they…” and I could name a movie star, they wouldn’t even… I mean, sure, there’s always little movie fans here and there, but it just mattered to them. It didn’t matter to them at all. They were doing something far more important.

And that was a real bucket of cold water. It’s like, oh, all these things. We live in this little self referential bubble that we think is so important and it just isn’t. And so I thought, you know, maybe I’ll just explore around a little bit just in life, you know.

And because I had gotten to do an expedition to the wreck site where I was really now becoming conversant with real deep ocean technology, I thought, why don’t I just go down that road. I know everybody, you know, I know all the scientists and researchers and submersible people and everything. So I just started creating expeditions and building new technical systems, cameras and lighting systems and exploratory vehicles.

And the other thing I liked about it is the ocean is unforgiving. Either your math is right or your equipment fails. It’ll implode, or the electronics will flood and it won’t work, and you’ll come back with nothing. And that’s not a critic’s opinion, you know, that’s one.

I came up with this idea, this principle that, you know, the second law of thermodynamics is not an opinion, it’s a law. It’s not some critics opinion. It’s not some journalist’s opinion. It’s not even a fickle audience member’s opinion or some blogger’s trolling opinion. You know, it either works or it doesn’t.

And I really enjoyed immersing myself in a world of hard rules. You succeed or you fail, not based on your art or your creativity or somebody else’s subjective opinion of your art, because the two don’t exist without each other. That’s the crazy thing. So as an artist, you bury your soul and you can be utterly rejected.

But ultimately, the point of art is to communicate with other humans. They may hate it, you know, so you put yourself at risk. I thought, you know what? I’m just going to go into an empirical world, a Cartesian world, where it either works or it doesn’t, based on good engineering. And that was good.

And I learned some really important human lessons in that world as well. Because when you’re offshore with a small team, it’s all about respect and cohesion and that bond. And when you come back to shore, you can’t even explain to people how hard it was or why it worked or what it took, you know, but that bond exists.

And then I realized, okay, we’re only as good as our team. And when I, after Titanic, I put together a team to do the impossible, which was Avatar. Nobody had ever made a film like that. It was a new form of cinema.

And I remember we fell on our a. Some of the first things we tried, we were face down on the ground and we’d stop in the middle of a production day and pull out a table and sit around it, and there’d be a bunch of glum faces because it wasn’t working.

And I said, “Guys, this may seem like the hardest day of the production. This is going to be the day you remember, because this is the day we write page 38 of the manual that tells the rest of the world how this stuff works. And we’re going to do it, and we’re going to figure it out.” It was… you know, Sullys never quit, right?

But… And then we did, and we figured it out, and then there’s such a feeling of pride and cohesiveness in the group after that, and you start to feel like, okay, bring the next challenge. We’ll figure it out. And the team spirit and the team morale is so high now.

This was 19 years ago, in 2006. The team spirit and the cohesiveness is so high now. People really… They hated when it all came to an end here a few months ago, as people dropped off one by one as the project was winding down, and everybody just can’t wait to get back to the next one.

Now, I don’t know, artistically, as a director, if that’s something I want to do right away next, there’s a pretty strong… I feel a strong pressure on my shoulders to do it, to bring that team back together because it’s so important for them, you know? And that’s not a bad reason to do something at all. You know, to make other people happy is not a bad reason to do something or to make other people feel fulfilled.

But I also have other things I want to do as well. So it’s a little bit of a… It’s a little bit of going off a cliff. I’ve told Susie, my wife, that I feel like I’m Wile E. Coyote in a Roadrunner cartoon, and I just ran off the cliff. I haven’t hit the ground yet. There’s that moment where my legs are pinwheeling in the air, you know?

But that’s okay. That’s okay. The scariest moments are always the moments of the greatest opportunity, I think.

Building Worlds, Building Hearts

JAY SHETTY: How do you… when you’re building a universe with people? You’re building lives and hearts and worlds that connect on such a deep level. I feel like when I’m listening to you, I’m… everything you do is highly emotional and emotive and heartfelt and deep, and you can’t help but cry when you’re watching your work. You know, maybe not Terminator, but… But what follows or maybe…

JAMES CAMERON: Maybe Terminator, too. When the Terminator goes… Come on. When he goes… But he goes down into the steel, and his POV goes to nothing. Come on.

JAY SHETTY: Yes.

JAMES CAMERON: People tear up.

JAY SHETTY: Yes. Yes. No, and so you see that and I’m… it feels like the emotion of creating it, whatever we’re getting out of it is because the emotion that’s creating is going into it.

JAMES CAMERON: Yes.

JAY SHETTY: And this team that you are curating is bringing all of that emotion, as you said, whether it was the Pandorans that are building the physical building in the movie or whether it’s the emotion that the characters are feeling and Tulkun is feeling and et cetera. How do you even start to detach from that as a team when you’ve been immersed in it for decades at this point?

The Uncertain Future of Cinema

JAMES CAMERON: Maybe you don’t maybe just keep going. I don’t know. Well, look, I mean, there are a number of milestones here that have to be met. First of all, the film has to succeed finally financially. And that’s not a given. Everybody just assumes it’s a no brainer.

But the theatrical marketplace has been dwindling and collapsing about 35% and it hasn’t rebounded. And people’s habit patterns have changed. And so the thing that I grew up and love and feel such strong sense of passion for may be becoming obsolete maybe.

And the cost of making movies is continuously going up and the demand is falling. So that’s a little bit of a death spiral right there, you know, and so maybe it’s… Maybe it’s going to be okay. We were sort of successful. If we can do the next one cheaper, we can continue. Right.

And then there’s also that wild card. You know, there are other projects that I have that I’ve been sort of sitting on in the background and there’s a thing that I want to do about Hiroshima. I bought a book recently, but it’s a story I’ve been following and, you know, excavating and researching for really my whole adult life.

It’s something that I really feel strongly I need to do at some point. It’s not a big film. Sounds like it would be, but it’s not a big film in the sense of an Avatar film. It’s not a four year commitment. It might be a one year commitment. So I need to do that.

The Weight of Living in a World of Dynamite

JAY SHETTY: And so why is that so meaningful to you? What about it?

JAMES CAMERON: I just think that we live in this world. I mean, I think Kathryn Bigelow’s film title is kind of growing on me, The Hurt Locker. It’s like we live in a house. Imagine you live in a house and you feel perfectly normal and you go about your business and you’re chopping onions for the guacamole and you’re going to watch your favorite show, but the basement is filled with dynamite, and it could go off at any moment. That’s the world that we live in.

It hits that metaphor. And so it’s not a metaphor. It’s our world. So I feel that we have a kind of a systematic forgetting of history, just at that remove. And we’re enough removed from the event of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that we need to be reminded what these weapons really are and what they really do.

Of course, the punchline of the movie is going to be the card at the end that says there are 12,000 nuclear warheads deployed in the world today. Each one is 100 to 500 times more powerful than the one that destroyed Hiroshima. And you’re going to witness it and you’re going to go through it with the main characters, and it’s not going to be pretty.

It might be a hard film to watch. In fact, it might be my least successful film. But I just feel it’s that thing of duty. You’re all about purpose. We define our own purpose. We choose purpose for ourselves. And it doesn’t all have to be obviously benevolent, like helping out a soup kitchen and easing the pain of others.

It might be something that’s more of a warning that helps guide us away from the rocks of destruction of civilization. As an artist, I think it’s important to consider these things and not feel powerless, because it’s easy in a world of 8 billion people to feel powerless. And yet empirically, I can look at it: I’m reaching millions of people. I’m reaching hundreds of millions of people with a movie like Avatar. Maybe I won’t reach as many people with a movie like Ghosts of Hiroshima, but I’ll reach some. And you never know. You never know that the causal chain that puts a person at a moment where they’ve been influenced by something.

Messages Woven Through Fire and Ash

JAY SHETTY: You have it even in Fire and Ash. I mean, that scene that you were referencing, without giving too much away of Quaritch actually arming, and there all of a sudden, you see the becoming of terrorists, like that idea of the government. All these messages are just—I feel like there are so many deep layers to the movie. You could keep going, whether it’s family, whether it’s racism, whether it’s equality, whether it’s equity, whether it goes down all the way through to government, fundamental politics that we’re seeing today. I mean, the movie is filled with so many powerful messages.

JAMES CAMERON: And just seeing each other. It all ultimately goes back to connection.

JAY SHETTY: Is that the root?

JAMES CAMERON: Yeah, I think so. There are two moments in the film where people say they see each other and they understand each other. And one gives you this feeling of vast dread when Varang says she sees Quaritch and she sees this vision of destruction. And for herself, she’s like Kali. Yes, right.

And then when Neytiri sees Spider finally, and there’s a bridge across the two species, across that divide. Because she becomes quite a racist in the film. And that’s by design. It’s like we take our most beloved character and we challenge you to really walk in her shoes and go the hard yards of what loss and grief can do.

And I think about all these people and everything that they’ve lost in the world, whether it’s in Gaza or Sudan or Ukraine or wherever. And how does that not generate just a hatred that will span generations? Well, that’s the cycle that we have to break, right?

Breaking the Cycle of Hate and Grief

Lo’ak says something at the beginning, and it’s kind of cheeky to actually say your theme out loud. I’m going to tell you what the movie’s about, okay? And he says, “The fire of hate leaves only the ash of grief.” But he doesn’t complete it, which is that from that ash of grief comes that fire of hate again, and the cycle perpetuates indefinitely.

So how do you break it? That’s the challenge, I think, that’s presented in the movie. How do you break it? And how do you know when it’s not about hatred and revenge? When you fight defensively for the things that you value, as opposed to offensively going out after somebody to punish them for revenge, to take what’s theirs?

And you see all of that happening in the world right now, all over the place. And you wonder—this is, I’m going to circle this back to AI for a second. The thing that the proponents of artificial superintelligence always say is, “Well, we’ll manage the alignment problem. We’ll align AI to our common good as human beings.”

But we can’t agree on a damn thing. We can’t agree on what’s right and wrong, what’s ethical, what’s moral. A Republican’s idea of that is very different from a Democrat’s, a Muslim, a Christian, a Hindu, a Shintoist, whatever it is. Everybody’s got a different opinion, and we can’t agree on anything.

So how are we going to suddenly form this wonderful moral consensus so we can teach it to something smarter than us that we can’t control? I mean, if that’s not the biggest recipe for disaster I’ve ever heard in my life, what is?

Now I am a science fiction fan, and it always goes into the darkest possible scenario, because that’s where science fiction goes, because it’s meant to be a warning to us about possible futures. But we’re living in a science fiction world right now.

The Power of Empathy and Connection

So I look at you, I look into your eyes. I see your kind of soulfulness and your enlightenment and all the things that you do and why you do it. And I think, all right, that’s why we’re going to make it. Because there are people who are practitioners of empathy and connection, and they’re out there and they are legion.

They just don’t ever seem to get into positions of power where it really makes a big difference. It just seems like all the wrong people elevate. I don’t know how you feel about that, and I don’t know if that keeps you up at night.