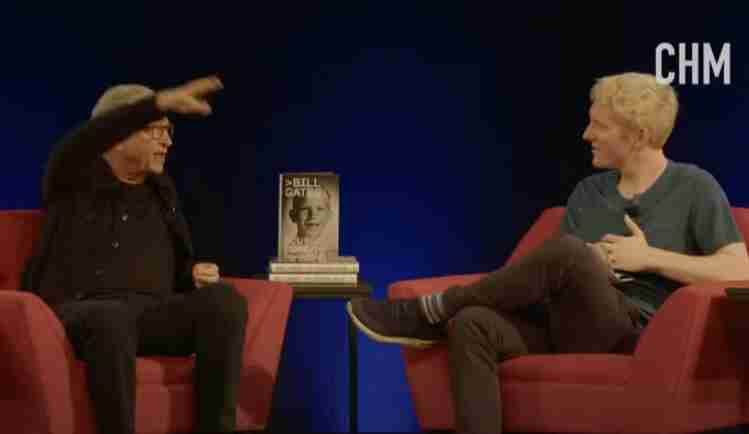

Read the full transcript of Bill Gates’ interview by Patrick Collison, cofounder and CEO of Stripe at CHM 2025. [Recorded February 11, 2025]. In this fireside chat, Bill Gates discusses his new memoir, Source Code.

Listen to the audio version here:

TRANSCRIPT:

Introduction

PATRICK COLLISON: Okay, folks. Well, thank you all very much for joining us this afternoon. Thank you to the Computer History Museum for hosting us. For those of you who are here for the first time, if you’ve not checked out their exhibitions, I heartily encourage you to do that. They’re really wonderful. But delighted to host Bill here and to have this discussion.

We’re going to spend 75 minutes discussing latest happenings in the credit card ecosystem. We’ll start with the book. So Bill, at a recent interview back a couple of months ago, I introduced you as the founder of Trafo Data. But I learned that that was not in fact—I thought I was doing the deep cut and the sort of—I’d really done my research, but I learned that was not in fact your initial enterprise and that Trafo Data was preceded by payroll and by your work with C Cubed. And so I just want to clarify, how old were you precisely?

The book was a bit ambiguous. How old exactly were you when you started the first business?

BILL GATES: Thirteen in eighth grade when the computer funded by the Mothers Club shows up, and that’s time sharing basic. But we spent money. We didn’t get paid for that.

But a lot of businesses in Silicon Valley are kind of inverted like that. Then PDP-10 was bought by a company in Seattle for time sharing, and they had to deal with digital equipment that if they found bugs, they didn’t have to pay rent.

And they didn’t pay us money. They paid us in computer time. So I got $5,000 of computer time. And then my next commercial thing was doing the scheduling program for my high school. And they not only paid me $10,000 to do the work, they paid me $5,000 to the computer time.

So the first time I had money in the bank from programming work was pretty much at the same time this travel data started generating cash and then the payroll program. So I’m 16 before I get real profit.

PATRICK COLLISON: So these days, startups are kind of in the air and everyone’s seen the social network and there’s—it’s kind of an understood concept. Was anyone else at the school thinking about starting businesses? Did anyone else start a business?

BILL GATES: No. Mark is several decades later, or strangely, I gave a speech at Harvard saying, “No, it’s fine to drop out.” And he was there.

PATRICK COLLISON: He was there, yes. So you’re radicalizing the youth.

BILL GATES: And it turns out we went to the same pizza shop that I went to recently. If you go at about midnight, they start discounting the pizza. So it’s a really good deal. And now the idea of doing startup companies, there wasn’t a venture capital industry. But were people even starting more prosaic businesses at all?

PATRICK COLLISON: Not people who went to Harvard University. No, no, I mean even before that, people in Seattle that you went to school with.

BILL GATES: No. This is like a pretty unusual atypical thing as a 16-year-old. And particularly well, having a company where you made money, that was considered a bit strange.

The idea of thinking ahead, okay, what are you going to do? How will you make money? How do businesses make money? I had my dad who would share about his law firm, so I sort of got the economics there and the kind of business disputes that came up. And then a friend of mine, Kent Evans, he was very much thinking about what career to go into.

He could have told you what the salary of a professor was, an ambassador. And that was kind of eye opening to me. He was the one who got me reading Fortune magazine and really trying to think, okay, how do these companies work? The company we admired the most was Digital Equipment because although their computers were still like $20,000 even for a PDP-8, they were the ones who were bringing the cost of computing down. It wasn’t just the mainframe, which was 20 times more expensive.

Early Exposure to Technology

PATRICK COLLISON: No, doing businesses, that was strange. I don’t think I’ve ever told you this story before, but I grew up in quite rural Ireland. And it wasn’t that long ago. But in the sort of mid-90s in County Tipperary, we couldn’t get the Internet because we were too far from the phone exchange, and there was kind of too much noise on the phone line. And so my kind of source of information and knowledge and so forth was the local library, which I spent a lot of time at.

And so my first exposure to the Internet was reading books about it. And these were books that had been written, I don’t know, in the early ’90s or something. Everyone was very excited about, kind of VR and, I don’t know, this kind of weird Tron-like stuff. So I thought the Internet sounded amazing. And then when I finally got the slow dial-up, I was like, “Wait, this is what everyone’s excited about?” But there was a book about this guy, Bill Gates, and how he started a company in his teens that I thought was pretty cool.

So, anyway, that’s what I learned in Tipperary. So it’s interesting to hear the Seattle version of that. So I want to jump a little bit forward and kind of touch on some sort of the—well, actually, we’re going to jump around a lot, generally speaking. But since we’re here in the valley, I just want to sort of touch on some aspects of it here. And so first, you’re frequently quoted as having made the claim that 640K should be enough RAM for anyone.

But it’s a kind of apocryphal claim as far as I can tell, and you don’t address it in the book. And so I just figured we had set the record definitively straight once and for all. One, is it enough? But then two, did you ever in fact say that?

BILL GATES: No, I never did.

The original Intel computer, the 8088, had a 20-bit address space. And so that was pretty good. But then they did this funny 286 that was very strange segment of memory that we told them that was the dead end. Finally, they got it right and did a straight linear 32-bit address space just like Digital Equipment had done on the VAX.

PATRICK COLLISON: When was the—the reason you told them they were doing it wrong or whatever?

BILL GATES: The 286 was—but you’re likely—you’re calling—I had a—Andy Grove—very tough relationship with Andy because he thought I was so brash. And you’re—how old is company? Oh, I’m 21. And they did two things we told them were dead end. The 286, we didn’t like the memory architecture.

And then they did this thing called the 432 that they wanted us to write software for. And we said that thing is also not very good. Just do a linear address space. And it turns out the 68000 Motorola did it first. And so when IBM was doing the PC, we said to them, “Hey, talk to those Motorola guys.”

And unfortunately, they couldn’t meet the schedule, so we had to go with the 8088, which is a form of the 8086. And that got us from the 64K bytes, which is what the 8-bit computers like the Commodore PET, Apple II, TRC80, those were all just 8-bit machines. We went from 64K to 1 megabyte, 16 bits to 20 bits, but we wanted 32 bits. And of course, later, we managed to even get up to 64 bits. Because memory goes from being ridiculously expensive to incredibly cheap.

Visiting Xerox PARC

PATRICK COLLISON: You ever visit Xerox PARC? Steve did, and you knew Steve well. But did you ever visit PARC?

BILL GATES: I visited PARC a lot more than he did. So one of my favorite nights was when I went to see Charles Simone.

So the original machine there, the Alto, Charles, who had escaped from behind the iron curtain when he was very young, it’s quite a story. He—

PATRICK COLLISON: Hungary, right?

BILL GATES: From Hungary, exactly.

Had written the first bitmap word processor called Bravo. It was his PhD thesis for Berkeley. And, it was so beautiful because they had Ethernet networking and they had laser printers. And he and I sat there for five hours and created a document, a typeset document that essentially became the agenda for Microsoft, do a spreadsheet, do a database. And it was this beautiful—back then, the idea that you could make your own typeset document was just so incredible.

And I said to Sam Altman and Greg when they came up to show ChatGPT-4, which is now almost three years ago, this was the most mind-blowing demo I’ve seen since the night I spent with Charles Simone at PARC. And of course, within two months of my spending that night with Charles, we hired Charles. And then Apple was hiring people like Bob Bellville, Alan Kay as well. So when Apple—there was a dispute where Apple would come to us and say, “You stole the graphics interface from us.” And we said, “No, no, we both stole it from Xerox.”

And so you have no claim whatsoever. The fact that Xerox actually, because of the legal situation they were in with their copiers, wasn’t choosing to file any patents on any of this thing. Who knows if that would have made any difference? But it meant that it was essentially an open source set of technologies that both Apple and Microsoft say, okay, let’s—first Apple does it with the Lisa, if people remember that. And then this crazy band, Steve—Bill Atkinson, does Mac.

And we actually—Microsoft, we have more people working on the Mac project than Apple does because it was just such a small group of people. But that demo, the Xerox Alto stuff, they tried to do a product called the Star, which died, but that was very influential.

Homebrew Computer Club and Modern Tech Movements

PATRICK COLLISON: So in the book, I was struck—you described visiting Homebrew Computer Club meetings. And today, in the Valley and indeed in the technology sector, generally, two sort of influential movements and subsectors are crypto and AI. And I think they have sort of something striking in common, which is they’re both cults.

And I mean that in a sort of in kind way, where, in both cases, they have fervent believers who—for whom these technologies become sort of part of their self-identity, and, they have this kind of really compelling mimetic power. Does that remind you at all of the homebrew computing movement? Or was that movement a very different kind of movement to these movements today? How would you compare them?

BILL GATES: Yes.

There’s a lot of similarities in that there were a small group of people who saw what personal computing would become. The slogan of Microsoft was “a computer on every desk and in every home running Microsoft software.” And sometimes we drop that last part because it seemed a little commercial. And the West Coast Computer Fair got going here. The first kit computer, the Altair, which actually didn’t ship until the summer of 1975, but it’s on the cover of Popular Electronics magazine at the end of 1974.

That’s the thing that gets me to drop out. My friend Paul Allen, who is two years older than me, I had helped him get a job at Honeywell so he could be there and bug me. And then this is the cover. And Paul had been saying to me, “Okay, it’s Moore’s Law, it’s exponential improvement.” And I’ve been saying to him, “Okay, this is unbelievable.”

Computing will be free. If it improves exponentially, it goes from being super scarce to super free. And then, okay, what are you going to do with it? Ken Olson, who ran Digital, famously said “Nobody wants a personal computer.”

PATRICK COLLISON: Unlike your RAM quote, he did say that.

BILL GATES: He did say that. He actually did say that. But there was a small group, and some of them were fairly counterculture. There was a thing called the People’s Computer Company. There was Bob Albrecht and various people.

PATRICK COLLISON: Will People’s Computers Company represent here at the back? Maybe grandchildren.

BILL GATES: And it had kind of this great feel that we were in on something. And it was almost like, okay, the big companies have the big computers. We’ve got the personal computers.

We’re going to change things. Even though those early machines were so limited in terms of what they could actually do, then as we get disks and we connect them together and the memory size gets to be decent, then the sky is the limit.

Silicon Valley’s Military and Counterculture Influences

PATRICK COLLISON: Steve Blank has just talked about sort of the military side to the history of the technology sector in Silicon Valley. And Lockheed did a big operation here. And during the Second World War, the NDRC funded a lot of research here, and there’s that whole side of things.

And then obviously, you have the humanist California ’60s, Ken Kesey, Berkeley, LSD, that whole version of things, Whole Earth Catalog, etcetera. When you were coming here, I guess, in the ’70s, did it feel more military inflected, military research, the fruits and the product of that, SRI, etcetera? Or was it the whole California hippie vibe?

BILL GATES: It was more, I’d say, the latter. There wasn’t that much military money in terms of Intel’s work.

Early Computing and Intel

BILL GATES: Later, when RISC computing gets going, there’s the North Atlantic audio network where they’re trying to detect Russian subs. And a lot of the original RISC computing is funded by a huge IBM contract. But Intel’s customers initially are not the military at all. They don’t have any government funding for the things they do. And even they were kind of stunned because they were chip guys.

And the idea of, okay, who’s going to do stuff with these chips? The 8008 was almost good enough to do a computer. It was used in a Japanese company, showed Intel how it could be used in a computer. It was used in a data entry terminal that Datapoint did. But it’s the 8080, which is 1973 that—so 1971 is 8008 and Moore’s Law.

And Paul shows me that. We’re still in high school. And I said, no, it’s not good enough. I can’t write a BASIC interpreter for that. Two years later, he shows me the 8080, and this thing is amazing.

It’s better than a PDP-8. It’s almost as good as the PDP-11. And I say, of course, I can write a BASIC for this thing. This is a real computer. And the list price for the chip is $70—but I mean $300—but MITS for that computer got a $70 price.

And so they managed to sell the entire kit for $300. Now if you really wanted to do something, you had to buy memory cards and a teletype. But for $1,000 you actually had a setup that you could run an accounting program or serious data analysis.

Family Influence

PATRICK COLLISON: Are you more like your dad or your mom?

BILL GATES: So both of my parents were massively influential. My dad, mostly by setting an example of being very calm, always on top of things.

You don’t have to make any decisions out of emotion. And so he was a lawyer and wanted to be a federal judge but never ended up doing that. Things with my mom were very intense, where she had very high expectations. She was disappointed in my manners. She was disappointed in how late I would be for things.

And even when she would ask me to do things, I would do things, she would always raise the bar a bit. So it was a wonderful relationship with a lot of intensity where I’d push back, stay in my room, give her a hard time, that type of thing. We had a lot of people come over to the house, and I sort of learned her value system in that after people would leave, she would say, “Oh, yes, the so-and-sos were here, and they must be so disappointed their kid didn’t go to college,” or “They went to some not very good college.” And so I’d be like, okay, that’s the way score is kept. And I told my mom, “Hey, you told me to go to Harvard.”

And she said, “No, I didn’t, did I?” And she was right. She never explicitly said, “I would be most impressed if you went to Harvard.” But she definitely just expressed her existential disappointment. She got that across very well.

PATRICK COLLISON: So are there differences in how you’ve tried to parent your kids as compared to how your parents did?

BILL GATES: Well, what’s mind-blowing is if you look—

PATRICK COLLISON: Did you do the intercom up to the—

BILL GATES: No. Yes. My mom had an intercom where she would wake me up by singing, which was very irritating because I’m a night person. If you wanted to use computers back then, it was great to be a night person because you would sneak into labs late at night. You almost had to be a night person if you wanted computer time.

So what was striking to me in writing the book, many things, but how much freedom my parents gave me. When we’d go off on hikes, I can’t imagine letting kids go off on these hikes where there were no adults involved.

PATRICK COLLISON: I was going to ask you, you’re sneaking out at night to go program and you’re going to these crazy hikes and so on. Like, can a parent today do that?

BILL GATES: They should, but they don’t.

PATRICK COLLISON: Do you?

BILL GATES: No. No. People are a lot more worried about safety. The idea of safety that, one in a million you might get hurt doing this or hurt doing that—other than driving, which actually is statistically dangerous for teenagers to do—they just had a pretty calm view about my traveling.

One summer, I worked in Washington, D.C. as a page. They didn’t come back. When I flew off to Harvard, they didn’t—

PATRICK COLLISON: And they’re not monitoring you on Find My Friends or something?

BILL GATES: Nothing like that. I mean long distance was expensive enough that I would call every two weeks or so. I didn’t send photos of what I was doing. And so that—the freedom that perhaps boys more than girls were given back then, for me, was valuable because I could have friends in hiking, friends at church, friends at school, different groups that I was sort of trying out different ways of working with friends.

PATRICK COLLISON: Would 19-year-old Bill founding Microsoft have been 19-year-old Bill without the exercise of that freedom over the course of his prior—

BILL GATES: I kind of doubt it.

I mean, I had a very optimistic viewpoint. And I had—other than one friend dying, I had a very idyllic childhood.

PATRICK COLLISON: And that very tragic death, certainly hadn’t known about before the book, I guess, is an example of how freedom is not totally free, right?

BILL GATES: No, that’s right. My friend Kent Evans, there were four of us.

When the computer shows up at this high school, at first, everybody’s in there, including the teachers. But then the teachers find it very confusing. So they leave. And eventually, there’s only four of us left. There were two boys, two years older than me, Paul Allen and Rick, and then Kent Evans, who’s my age and my best friend.

And we’re all—that’s Kent there. We all go nuts because we’re making the computer play tic-tac-toe and play Monopoly. And slowly but surely, we’re really getting—

PATRICK COLLISON: And you got started early. The computer is playing Monopoly.

BILL GATES: So anyway, my friend who is my age was no more coordinated than I was. So it was kind of surprising where he signed up for a mountain climbing class. And that—in that case, tragically, as they were practicing, he hit his head and died when I was—he was 17 and I was 16.

Young Founders in Technology

PATRICK COLLISON: So is it—can you name any—just offhand, can you name any founders who you think are at the very top of the technology industry today who are in their 20s?

BILL GATES: Today, they’re in their 20s?

PATRICK COLLISON: Yes.

BILL GATES: Alex Wang, who does the AI data, he’s still in his 20s, I—

PATRICK COLLISON: I think he’s 29.

BILL GATES: 29, maybe, I don’t know.

PATRICK COLLISON: The reason I asked this question—and to be clear, Alex would also be my nomination, but I would really struggle to give you kind of a second person. And the reason I ask is because as I kind of take stock of the industry over the past half century, you and Steve Jobs and Michael Dell and Marc Andreessen and Mark Zuckerberg and—I guess Larry Ellison was a little bit older when he started.

But yes, like at any moment in time, I feel like there was a very clear person in each decade who’s really at the apex, at the forefront of the sector and who is in their 20s. And today—skilled, amazing company, but it somehow seems harder. And again, even if Alex is wonderful, but it’s harder to kind of go further down that list. Is there a phenomenon here? Do you think there’s something to explain?

BILL GATES: Well, the virgin territory—when the microprocessor, the miracle of the microprocessor and the optic fiber and the disk storage and cheap memory chips, all that stuff is changing what we can do with computing. The existing companies don’t get it. I mean IBM does do the IBM PC. That’s a long story. But they essentially stick to what computing was for when the computers were still very expensive.

And they, in particular, don’t get software or things being online. And so there’s just—young people have a way of being more open-minded. Like when Paul tells me it’s going to improve exponentially, and I have the math skills to know that that is just crazy. And everybody should be going, “Oh my god. This is wild.”

But even when I’m back at Harvard telling my professors, “Let’s work on microprocessors, this is coming,” my main professor was like, “Look, if you’ll just be quiet, I’ll sign whatever you want me to sign. You can use any computer, don’t keep giving me that futuristic thing.” And so all of us, Michael certainly—Michael Dell, Steve Jobs, we’re in on the ground floor. The fact that our companies endure, okay, that’s—there’s something more going on there because there’s a lot of early companies. I mean, in fact, either around this museum or in their warehouse, there’s 30 minicomputer companies.

There’s 30 personal computer companies that nobody’s heard of, because it was a very dynamic time. I think it’d be a lot harder now. I mean, you’d basically have to have an insight that the existing companies don’t get. And in the case of AI, is there—well, of course, OpenAI is kind of new—NVIDIA’s success, although he was in graphics chips for a while. But the fact he’s in the Magnificent Seven, he’s—and he’s not young, but his company is newer.

And so it shows that, okay, there is some fluidity. Intel did not do AI chips. And who knows? It’s weird because Intel, for me, Intel is mythic. I mean, they are the place—when we would come to see Gordon Moore and Andy and give each other a hard time about things.

That was so important. This Wintel, the Intel chips and the Windows partnership really from—in the ’80s and ’90s drive all of this stuff. So I don’t think we’ll see quite as many companies started by dropouts in this area. It’s more—

PATRICK COLLISON: So I just about made it at the last—

BILL GATES: No, I’m always impressed how young you are. It’s—

PATRICK COLLISON: I’m getting more gray-haired by the day.

Influence of Psychedelics

PATRICK COLLISON: But since we run a financial services business, I think it’s helpful. So Steve Jobs used to describe in sort of in public remarks and so forth how dropping acid and doing LSD had influenced him and, I don’t know, gave him a more transcendent sense of beauty at Apple or whatever it was. In the book, I read that you also partook. Did LSD change your outlook on anything?

BILL GATES: Definitely not.

Paul Allen, who’s two years older than me, always got a kick out of—he was into this Jimi Hendrix song, “Are You Experienced?” So Paul gets me drunk. Paul gets me pot, hash, eventually, acid. Just—he gets a kick. That’s Paul.

PATRICK COLLISON: Checks out from the photo.

BILL GATES: And the insult that Steve Jobs said was that if Bill Gates had dropped acid, maybe his products wouldn’t be so poorly designed. And I said to Steve, “Look, I got the batch that was good for engineering. You got the batch that was good for design. I’m sorry.”

I wish I’d had that—your batch too. Would have been a nice extra skill set to have. But no, I mean, you always think you’re thinking profound thoughts, and then afterwards, you wonder if your brain has been permanently damaged. So I gave that up fairly early on. The worst thing was I—one time, I took it, and I had a dental operation the next day, and I decided that was a bad combination.

Diet Coke and Productivity

PATRICK COLLISON: So speaking of pharmaceutically active substances, so, well, I’m curious kind of when did the Diet Coke start? But more importantly, there’s a theory that my friend expounds that I think does bear some explanation of how John Carmack and Buffett, Sheryl Sandberg, Bill Fenton, all these people of titanic productivity, what do they all have in common? Of course, they are prolific Diet Coke consumers. And so is Diet Coke an important part of the Bill Gates productivity story?

BILL GATES: Yes.

In the early days, it was—

PATRICK COLLISON: How many are you talking a day at your peak?

BILL GATES: Twelve, fourteen. A normal number. I mean it all has to do how often you want to go to the bathroom. That wastes time.

So my main way of getting calories was I would get bottles of Tang. And instead of using water, I would just pour the Tang onto my hand and eat it. So I would always have kind of an orange thing on my hand and my face that people found unattractive. But I have to say in terms of efficiency of getting calories into your body, it was phenomenal. I was in my 30s when I switched from normal Coke to Diet Coke.

When I was young, I was just so hyperactive that people were worried that I was too thin. They would try to get me to eat more. I would go to meals when we were talking about Microsoft. And at the end of the meal, be like, “Well, I don’t think I’ve eaten anything.” I was kind of talking the whole time.

And adrenaline helped me through. And we’d stay up nights and do work, which I can no longer do that. But—

PATRICK COLLISON: More advised than the next—

BILL GATES: Now Diet’s fine, it’s still got the caffeine, which is the key ingredient.

PATRICK COLLISON: So you were 16 in 1971. And there’s a website, I’m sure some people here are familiar with this, wtfhappenedin1971.com, showing how all these long-run trends pertaining to society writ large, the trend line inflected around 1971.

Historical Trends and Societal Changes

PATRICK COLLISON: You see that maybe most basically in TFP and total factor productivity, but you also see it in things as diverse as fertility and just like this incredible cornucopia of different society-wide metrics. And so you had an adolescence before 1971. Experienced and remember the late ’60s, and then obviously you’ve been here for many years afterwards. So what happened in 1971?

BILL GATES: I don’t know.

I think it’s a little bit to attribute it to a single year, you have to stare at it a bit. Okay. A bit around then—did it feel like society changed in any recognizable or characterizable way?

Well, the ’60s were a period of incredible economic growth. ’50s and ’60s are America’s really incredible periods. The ’60s were very tumultuous.

Have the—John F. Kennedy is killed, Robert Kennedy is killed, Martin Luther King is killed. And so actually—

PATRICK COLLISON: And you have this generation of—these are very kind of peer events in your childhood.

BILL GATES: Yeah. And you have hippies and drugs and a real feeling of, okay, the country has this divide.

Not as bad as we have now, but, back then, it felt like, okay, are we breaking off into two different ways of looking at things, the so-called silent majority? And you have a lot of unrest in the inner city during the summers that people are concerned about. You start the war on poverty. I think in terms of innovation, the ’70s are amazing because as the chip comes in, the underlying digital fabric, it’s really hard to overstate how inefficient things were before we had that. And actually, the way economic figures work, because they have a hard time adjusting for quality, it doesn’t really show up in the economic figures.

You get all—as Solow said, you get all the way into the ’90s before you really start to see that, okay, this must be personal computers coming in and changing these things. In the technology sector, the way they measure productivity, it did show it. But then it starts showing up outside of just our narrow industry. It is weird to think back then we were very afraid about Japan. Japan was almost like China is today where you’re like, “Oh, they must be cheating.”

No. They never really invented anything. Have to stop them. Oh, they must be subsidizing it or something like that because Japan was so incredibly strong. In fact, Microsoft in the 1970s, we had several years we did more business in Japan than we did in the United States.

PATRICK COLLISON: Really?

BILL GATES: Yes. We had incredible—a number of great companies over there, Hitachi, NEC, that were buying our software. And it was phenomenal. And it was—for us, it was fantastic because learning how to do business globally, that’s incredibly valuable because we have a scale economic business with huge fixed R&D costs and no marginal costs.

So if we sell to 7 billion euros versus 330 million euros—that’s a very, very big deal. And Japan really got us into that, in a big way. So the ’70s, eventually you get to the end of that decade, people are worried about inflation. And Jimmy Carter is wearing a sweater telling people to turn their temperature down. It’s so funny because when you’re in a company that’s growing so fast, the idea of what’s GDP growing at, I couldn’t even tell you year by year in the ’70s what the GDP growth was because it was so irrelevant to somebody coming in—

And we were basically, we were able to double our sales every two years for about 18 years there.

Global Risks and Nuclear Threats

PATRICK COLLISON: In the book, I was struck, and you tell a story about the explosion you heard when—I can’t remember what age you were, but young. And you’re worried about some kind of attack or something, military or nuclear war or what have you, and it turned out to be a tornado ripped through your garage. But I’m curious, that was such a looming present risk and danger in the 1960s and I guess through the 1970s as well. With the foundation, you think about global risks. You know you wrote the pandemic book, etcetera.

Is nuclear war like—nuclear war now has this kind of anachronistic, atavistic feel to it. It’s a thing that people worried about in the ’60s and ’70s, but we don’t really think about as very central or present today. In the context of the foundation, global risk, do you think at all about it?

BILL GATES: Well, I’d still put—there’s about four or five things that are very scary. And the only one that I really understood and worried about a lot when I was young was nuclear war.

Today, I think we’d add climate change, bioterrorism slash pandemic, and keeping control of AI in some form. So now we have four footnotes. In terms of nuclear war, it is very scary to me that people are complacent because we have done so well. We haven’t—we’re here. Since World War II, we haven’t blown up any nuclear weapons and killed people.

And yet, you know, there was kind of an assumption that you’d have really calm, thoughtful leaders who weren’t going around threatening each other, that you would renew these treaties and avoid wasting. The U.S. Government has the plan to, I would say, waste many hundreds of billions of dollars redoing not just one leg, but all three legs with new weapons. It’s unbelievably expensive.

It causes other people to do the same thing. So nuclear, it’s even stronger if you talk to Warren Buffett that that is the thing, you know, and that’s probably why you fund nuclear threat initiative. But it shouldn’t be taken off the list of things to say, this could be a problem. And the idea of making fissile material, there are now techniques for making fissile material using lasers that are completely undetectable. So it’s different than when you have to use centrifuges and things that require a lot of energy and fairly unique steel alloys to do.

Now a non-state actor can make an atomic bomb quite easily.

Neurodiversity and Personal Reflections

PATRICK COLLISON: In the book, you say at the end, you say that today, if you were growing up today, that you might have been diagnosed as on the autistic spectrum or neurodivergent or something. Peter Thiel, in his book, Zero to One, said that autistic founders do better because they are more contrarian and they don’t pay as much attention to what other people think and so on. Thoughts?

BILL GATES: Peter is a contrarian.

I will grant him that. And for me, the ability to concentrate, to get fascinated with something and really dig into it, which as I got older, I could choose what I concentrated on. And when I was in high school, I was okay at it, but I remember being down in my room thinking, okay, I’m going to work on my homework and do really well this year. But then there were these Tarzan books that were so interesting. And then by the time I got to Harvard, where I would do this thing that I—I didn’t go to class and try to do the work at the end, then I could, every time, you know, when it came to it, did manage to not read the Tarzan book equivalent of that time, but really work on that course.

So I think being a kind of student who can take, say, a 400-page book about a new topic and really spend the time, take notes, admit to yourself, okay, I’m confused about this, I don’t understand this, to be as a really concentrated student, I think it’s super valuable. And so the mix of things that I got by almost certainly being on the spectrum, late social skills, very fidgety. I rock sometimes that bothers some of the people around me, because I don’t even know what I’m doing, but apparently, it’s not that attractive. So I’m at age 70 now, I’m going to—I turned 70 this year, so that’s part of my resolution is to give up rocking. We’ll see.

PATRICK COLLISON: I thought you were going to say the opposite. It’s like with Don Knuth with TeX, where I guess the versions are converging on e. But at some point, he said that, okay, we’re done. And from now on, all bugs are features. So I think you can also adopt that mindset.

BILL GATES: Might have to. Exactly. All bugs are now features. So it definitely implied—been given the ability to get rid of those things so that I would be normally socially in those things, it would have been to my detriment. And nowadays maybe getting that diagnosis is helpful to people to understand that, okay, why they’re better at some things and worse at other things.

Amazingly, my parents actually did send me to a therapist not because of any understanding of mental conditions, but just because I was being a bit tough on them. And they wondered if this therapist could help, which at first I thought—

PATRICK COLLISON: And did they?

BILL GATES: Actually, the therapist was brilliant. He, over the period of a year, gave me various tasks, had me read Freud. And he was explaining to me it was not a sign of merit to be able to bother my parents, that any dumb kid could do that because they loved me.

And if I wanted to kind of take on something hard, my parents were actually my allies at helping me with the outside world. And at first, that was frustrating to me. But then I realized, okay, this guy is right. This is a fake thing. Like when my parents would say, go to bed at this time, and I would say, that is truly arbitrary.

That was not the path to the future. And about that time, I have the therapist helping me out and also the computer shows up. And so my energy—I realized, okay, I can pour my energies into this thing instead of giving my mom a hard time.

Trust in Universities

PATRICK COLLISON: So you mentioned Harvard. Trust in universities, I’m not going to ask you too much about your time at Harvard since you only spent how long there?

BILL GATES: Two years.

PATRICK COLLISON: Yes, exactly so. We’ll ask you at university today instead because your kids spent more time at Harvard or at university, I mean.

BILL GATES: Yes. I have a daughter who got out in three years, but the other two used all of four years.

PATRICK COLLISON: Okay. You’re a relative expert in contemporary universities, so at least vicariously. So trust in universities has declined by 20 points since 2015 in the higher education sector. This is kind of the long-running, longitudinal Gallup trust survey. And so trust in universities now sits at 36 percent.

And so like one-three of people trust—trust universities—trust higher education. What do you think is going on?

BILL GATES: Well, I’d say two things there. The first is a general phenomenon about trust. You know, so when they ask the Chinese people, do you trust your government, you know, like 80 percent say yes.

The—those are the people who don’t pick their government. We’re the people who do pick our government, and we have a 9 percent trust level. So there’s a broad phenomena that applies to basically every institution, a little bit less to the military, until very recently, a little bit less to the judiciary, but now that’s come down a lot. So in a way, it’s not that surprising that higher ed is part of this. But then there is some specific things going on in higher ed where certain doctrines can’t be questioned.

And if you question them, then maybe you shouldn’t speak at all. And this countermovement against that, although we have to be careful that we don’t throw out a lot of good things, as we swing the pendulum back the other way. But, my son chose U Chicago because they were—the first. One of the first who said, if you think there’s a thing called the microaggression and if you think somebody standing up in front talking to you about history is going to bother you, then you should not come to the University of Chicago. We’re just not going to be engaged in that, so we’re going to pick a student body that’s ready to debate things.

And I think that fortunately, they were able to slowly but surely—and even Stanford’s going through some things now about, okay, what were they doing in terms of allowing speakers? So will those trust numbers go back up? Trust numbers rarely go back up. And that’s got to be concerning as you have big change in society coming primarily from AI and people saying, okay, here’s how we should change the job market or taxes. Well, if you don’t have somebody you trust who’s helping to think that through for you, that is a bit concerning.

And so I hope and I think universities, particularly U.S. Universities, are an incredible asset for the country and for the world. I support, the Gates Foundation supports a massive amount of medical research at places like Stanford. The understanding of the immune system that’s coming out of that group is not just for the diseases, the infectious diseases, but for all diseases is going to be incredible.

And so I hope we can renew the trust because we do need fair arbiters who are thoughtful and take a very long-term view and aren’t profit focused.

PATRICK COLLISON: So I’m a big fan of Tyler Cowen’s interviews, and I was thinking, preparing for this, what would Tyler ask. And so you mentioned University of Chicago. William Rainey Harper, the founder, I think he was a Baptist minister before founding the university. Two of your parents were Christian Scientists.

Religious Influence

PATRICK COLLISON: Well, my—

BILL GATES: So all grandparents. Yes. All four of my grandparents are devout Christian Scientists. So my parents are raised as Christian Scientists, which is a form of Protestantism that has a lot of great things, but it’s very strange in that it doesn’t believe in seeking medical help. And they—my parents bonded over their rejection of Christian Science.

PATRICK COLLISON: So my Tyler Cowen question is, in what way was Microsoft culture influenced by Christian Science?

BILL GATES: Well, all my grandparents would sit in the morning and read—there was a daily lesson from Mary Baker Eddy, and it’s about—it’s not so much about don’t go see doctors. It’s more about your values and how you help other people in your life. And so the strong influence of my mom’s mother, who was widowed when I was five, so she and my mom was the only child, so she was very much in our family. Her sense of values and morals influenced me both through my mom but also very directly.

And when I got into a potential disciplinary thing at Harvard because I’d taken Paul Allen in to use this computer, and then when they finally audited this computer, they realized the sophomore had used 60 percent of the time. And they were thinking, okay, how do we explain that to the government? Because we were simulating the 8080 microprocessor, which is a brilliant thing that Paul Allen came up with so we could have these incredible software development tools. Anyway, when I was under examination by Harvard, she wrote me a note to say, “Hey, please be careful. You’ve got to worry about your reputation.”

And so I think the good parts of religion and Christian Science in particular were helpful to me. Obviously, I believe in the science of medicine. Not all cabinet members do, but that’s okay.

Communication and Business Practices

PATRICK COLLISON: So in the book, again, you describe chatting back and forth with various people you’re doing business with, like, again, Steve, but also others over phone and exchanging letters. And I guess one did business differently in the ’70s as compared to today, where it’s, I don’t know, texts and emails and Zoom chats and so forth.

Are there any redeeming merits to those now antique technologies? Or is it—are the new modes we use today just all a free lunch?

BILL GATES: Well, I think it’s even harder today to step back and really spend time thinking about things. The news is bombarding you all the time, and it seems kind of interesting. And it’s even worse if you’re a CEO where there’s some customer or employee that something’s going on all the time.

PATRICK COLLISON: And you didn’t even have Slack in your time at Microsoft.

BILL GATES: Not at all. And we became an email culture company very early on. But, when I would get time every year, which was two weeks a year to take these ThinkWeeks where I wouldn’t be on email the whole time. I would just be reading papers and writing strategy memos.

PATRICK COLLISON: And no smartphone blinking beside you?

BILL GATES: Nothing. No TikTok and—none of it. I just took literally things that were either in books or printed out and sat there and thought. And then at the end, I would write a long memo about what the Microsoft strategy should be.

So I think even more today, pulling yourself out of that constant stream is very, very important.

AI’s Impact on Microsoft and the Gates Foundation

PATRICK COLLISON: Will AI be a bigger deal for Microsoft or for the Gates Foundation?

BILL GATES: Well, AI is such a big deal for everyone. I think of the digital revolution that got us up to this point as sort of just the free computing, storage, communications, so all the digital stuff essentially free. What’s still scarce is intelligence.

When you say, okay, how do we eradicate malaria? How do we finish polio eradication? Those are things that I enjoy working on and assemble very smart people and talk about, okay, what’s going well, what’s not? Do we need new tools? We don’t have as many medical experts, people who can stay on top of everything or people who can do math tutoring in the inner city.

We have a shortage of intelligence, and so we use this market system to kind of allocate it. AI, over time, and people can argue about the time frames, will make intelligence essentially free. So even a question like design a drug to do this thing, the digital system will do a faster, quicker, more thorough job than any set of humans could. And so that’s so profound, it almost gets you into philosophical territory. I think for the Gates Foundation, the idea that AI, instead of being available in rich countries and then 20 years later in these developing countries, that we can play a role that patients in Africa may have AI medical advice even sooner than the highly regulated, rich world markets do is actually very cool.

One of the projects we have, we do a lot in agriculture because that is important for nutrition and incomes. I want the poorest African farmer to have better advice about whether, when to plant, what to plant, all of these practices than the richest farmer in the world has today. And by using AI, and it’ll be assembled for many companies, Google has some great stuff, Microsoft has great stuff, we can empower that farmer. So I think the answer to your question is even though it’s existential for Microsoft, the ambition level that the Gates Foundation and everybody who wants to help in developing countries should have is so much more aggressive, so much more exciting than it was before AI came along.

Childhood Influences on Philanthropy

PATRICK COLLISON: Is there anything about your childhood, if I’d known you, when you were 16, that might have led me to predict that you would undertake the particular kind of philanthropy with the Gates Foundation that you have?

BILL GATES: No. I mean, you’d see that my parents volunteered a lot and were very, very involved in the community. My dad’s book he wrote was called “Showing Up for Life,” where he always wanted to be part of the community and helping out. They were very involved in United Way. That’s why I’m giving the proceeds from the book to United Way.

And so you would have seen a strong set of values there. But even I remember when my mom was saying to me, “Hey, you need to do this payroll deduction.” I’d be like, “We’re really busy, mom. And a lot of our employees don’t come from this community. So do they really know these things?”

And she was very convincing. And so Microsoft, to this day, which I’m very happy, is very engaged in United Way. But no, my—certainly until I get into my 30s, my mindset was there’s all sorts of other wonderful stuff going on. I’d love to be polymathic. I’m reading about the latest in many different sciences, but I am going to focus on Microsoft.

And so from my 20s, was monomaniacal. I did not read broadly. I definitely intimidated my competitors. My favorite panel was one about graphics interface where it had people like Mitch Gabor or Fred Gibbons. And at the end, everybody’s telling me that graphical centerpiece is a mistake because the computers aren’t fast enough, the memory’s not big enough.

And at the end of the panel, Mitch said, “Bill’s wrong, but he worked so much harder than us. He’s going to win. And so we should just give in.” And I thought, well, that’s nice. Thank you.

And eventually, in my 30s, in the year 2000, actually, that’s in my 40s, I turn over the CEO job. And then I let myself go back to reading about a broad set of things. And it’s been a great joy, all the things I’ve gotten to learn at the Gates Foundation. But even in the ’90s, when I think, okay, what am I going to give this money back to, the idea of, well, have all the philanthropists taken the high impact things, and so what I’m going to find isn’t going to be that good. You can say it’s a tragedy that—take something like malaria.

When I do the first $30 million gift for malaria, I become the biggest funder of something that kills a million children every single year. And it’s like, what? Okay, they did leave this one for me to work on. So I think we can get a Microsoft-like result, i.e., leverage of dollars spent will be gigantic, even though it’s weird that that wasn’t being taken care of.

Energy and Nuclear Power

PATRICK COLLISON: You write a lot about it. You think a lot about energy. And we’ve—we’ve debated it. Solar and wind were two quantitative questions, but you like math. So solar and wind were 30 percent of electricity generation in Texas in 2024, up from 10 percent in 2014.

What’s that number in 10 years?

BILL GATES: Well, the big thing you have to predict is what happens with nuclear. Nuclear, of course, comes in two forms, nuclear fission and nuclear fusion. And I’m of the belief that in the 2030s, early in the 2030s with fission and later for fusion, that that electricity can be cheaper, as cheap as solar energy and nearer to where it needs to be used and less weather dependent. And so there really is no floor to how cheap fission or fusion can be.

Now people make fun of the fact that every such prediction in the past turned out to be utterly wrong, and the nuclear industry basically went bankrupt because the reactors were too expensive and they hadn’t solved safety, waste, proliferation. But, so I think those will come in, and I may be biased because I’m very involved in both fission and fusion activities. For solar, there are potential ideas of how you do storage. It’s very hard because it’s not 24-hour storage. Any pool can do 24-hour storage.

This is annual storage for extreme conditions, and the economics of that are very difficult. We’re making an amazing amount of progress on geothermal energy. Companies like Fervo are coming in. That’s a Breakthrough Energy backed company. But I’d say it’s the exact mix, there’s a path dependency here.

If we don’t get the nuclear paths to work well, then you better hope that some miracle of storage takes place. Because if you want to have no emissions and electricity cheaper than it is today, those are really the only—it’s—it’s nuclear playing a big role or some miracle of storage that makes it come together.

PATRICK COLLISON: One of the first times I ever met Bill, I sort of tentatively and nervously put forth my theory about the possible future success of solar. And he told me it was the stupidest thing he’d ever heard. And so if any of you worry that Bill is not—and by the way, of course, he then proceeded to explain in great depth and with references of extensive calculations how it was, in fact, poorly founded idea.

So if any of you worry that Bill is not applying himself with the same level of intensity to problems today that he did to in the past. I would like to fully reassure you.

AI and Labor Economics

PATRICK COLLISON: So the labor share of GDP today is about 60 percent, and it’s been stable since World War II. Do you—given AI and all the rest, what do you think that number is in 10 years?

BILL GATES: Well, all these economic systems are kind of designed for this shortage situation that we’re talking about, a shortage of doctors, a shortage of food.

And the whole idea of you have individual actors and you use this price mechanism to discover these things. When you get into the world of AI, it’s very, very different. And labor will not be a scarce input. Now there are social reasons in terms of motivating people and organizing society that you want jobs. Jobs are not another input like coal or wood where, okay, it’s not competitive.

Too bad. You really do have to think, okay, how do young people get motivated to learn and engage and how do we do things? But it’s always strange to me when you read—you’ll read in the same publication, “Oh, we have aging societies, that’s a big problem,” and “We have the robots are coming.” Well, the aging society problem is solved by the robots are coming. So you can stop worrying about the aging society problem.

If we didn’t have AI, you could have fun thinking through how Japan and China are on the cutting edge of something that, other than Africa’s, is happening in the entire—

PATRICK COLLISON: In those scary population pyramid charts, we just need to add robots, then it’ll look much, much more reassuring.

BILL GATES: Well, you may not put it on the same chart. But in terms of output per human, the robot output will—without adding humans, it will raise that number very, very dramatically. And so it’s a very different economic system. The labor share goes down a lot.

In fact, you need things like the tax credits, EITC tax credits, that kind of encourage the use of labor even when if without that incentive, you wouldn’t use the labor. And so we may see tax—we have taxes on labor today. And, in the future, we’ll have subsidization to labor. So it’s a very different tax system in that the—what I call the robot tax that some observers didn’t fully understand. But a tax on capital, that is the non-labor piece, you’ll get all your taxes from the capital sector, and you’ll use that to subsidize into the labor sector.

And so that’s almost the opposite of the tax system that we have today, and that helps you make the transition.

Microsoft’s Location Decision

PATRICK COLLISON: Four final questions. Would Microsoft have been more or less successful if it had been started or had moved when you, I guess, moved from Albuquerque if you’d moved to the Bay Area rather than Seattle?

BILL GATES: Yes. So when I—my first customer is in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

I didn’t know how to spell Albuquerque, but that was our customer. And so when I drop out in 1975, we’re in Albuquerque, New Mexico until 1979. That customer, MITS, gets bought by a California company. That’s quite a while.

PATRICK COLLISON: That’s quite a while.

BILL GATES: Quite a while. And so we know that we can’t hire the people we want to hire into Albuquerque. And so I—that’s—yes, those are our offices. And it’s just not the best hiring track.

BILL GATES: Around the corner, there was a massage parlor, but it wasn’t the high rent district. And so I had three ideas. One was to go and be right next to the Dallas Fort Worth airport because they had good connections to Tokyo. That I dropped fairly early on, although I got a kick out of it. And so is Silicon Valley versus Seattle.

And I knew Silicon Valley, and you’ve got Stanford, you’ve got a lot of partners there. But I just didn’t think we’d get enough distance in terms of our unique take on the industry. And my concept was to be a software factory and just write lots of software. So we had the best hiring process, the best compilation, debugging process. It wasn’t about any individual piece of software.

We were just going to write software faster than anybody else. And most all my competitors, literally until Google comes along, which is way more than a decade later, I’m competing with single product software companies. So Ashton-Tate has dBase, MicroPro has WordStar, WordPerfect has WordPerfect. These are single product companies. And they’re just not moving when it comes time to do graphics interface.

They can’t do it fast enough. When it comes time to do Office, which is a bunch of software working together over your exchange data, they can’t do it. So I didn’t want my concept—

PATRICK COLLISON: I’m sad we never had to compete with you.

BILL GATES: I didn’t want this concept. Like I always had this thing that if you edit code, can you be debugging it two seconds later, which is incremental compilation and linking and all sorts of ways of doing testing that are very software intensive, which are just factory kind of things.

And I didn’t want people in Silicon Valley to understand how we conceived of these tools and go and duplicate these tools. Unfortunately, unfortunately, that never happened. Google just decides that hiring lots of smart people and letting them do lots of projects because their search business is such an incredible business, they come in and they’re like us, like, okay, we’re just going to do any kind of software. And they were even more lax than us. They didn’t even need to write a business case.

If they thought something was cool, they would fund it. And I envied their kind of way of going about that. Anyway, so I ended up picking Seattle. And there was a slight bias there in that my parents were there, Paul’s parents were there, and I—that was a community I knew. It was strange because I had told my parents, “I’m not coming back” when I left because there was no industry in Seattle that was going to engage me.

So I hadn’t contemplated that I could decide where to be. So I think it worked slightly better, but I doubt it would have made a big difference. I mean, and eventually, we have fantastic offices down here.

Microsoft’s Success and Competitors

PATRICK COLLISON: So there’s an amazing and I guess you just named some of them, cornucopia of software companies and competitors and Wang and Digital and Lotus and all these folks. Microsoft is, I guess, depending on the day, but often the largest company in the world, those companies are defunct.

Why did Microsoft survive?

BILL GATES: Well, our basic concept of writing lots of software and selling it globally, that was correct enough, and we were more serious about that than anyone else. And so we—the number of products we did is myriad. And you’re in the learning loop. If you have a very popular software product, your customers are telling you how to improve it.

Your customers are getting used to your user interface. You make it extensible, so there’s some add-on things that are actually not necessarily going to be portable to whoever tries to come into that category. And I remember when we were competing against 1-2-3. 1-2-3 from Lotus owned the spreadsheet market, and we’d go into a meeting and people would say, “Hey, we’re making a better spreadsheet.” And I’d say to them, “There is no spreadsheet market.”

There’s only a 1-2-3 market. You have to make a better 1-2-3. You have to run those macros. You have to superset everything about it. And somebody thought we should name our columns differently and that it was better for some theoretical reason.

And I was like, “No, that’s because you think there’s a spreadsheet market. There is no spreadsheet market.” And so we were reasonably hardcore. And there were junctures like when the Internet comes along where people say, “Oh, Microsoft doesn’t get the Internet, Netscape gets the Internet, and Microsoft doesn’t get the Internet.” It was true.

We had to really adjust to stay on top of it. There were people who thought workstations, like Sun Microsystems workstations, were interesting. They were just expensive personal computers from my point of view. And Scott was not the friendliest towards Microsoft. But it was inevitable.

I mean, what was unique about these workstations? They were just very expensive personal computers. And so we didn’t think—honestly, though, we didn’t think as much about our competitors as they thought about us, because we just had a lot of profitable products and we’re doing things broadly. We were also running scared. I mean, literally until the late 1990s, I thought, okay, the next year, we could mess up, somebody could get ahead of us.

So we always ran scared. We were good at controlling our costs. And then it’s amazing, yes, we are very successful, but so is Amazon, Google, Apple and Nvidia. I mean it’s incredible that these companies that shared in the digital revolution with us are the seven most valuable companies. When I’m growing up, it’s oil companies, car companies, banks, NTT DoCoMo, the most valuable—does anybody know them?

Most valuable company in the world. And so the digital revolution, collectively, we were so right that we did build the world’s most valuable companies.

Windows Card Games

PATRICK COLLISON: To the point of building all the software for all use cases, you mentioned your grandmother’s affinity for cards and how she’d win all the games, etcetera. Is that why Windows has the card games?

BILL GATES: Yes.

I mean, I—the first thing that I actually figured out there were algorithms, kind of hidden algorithms, that if you thought about them carefully enough could help you was playing cards even before I got into math. We put that card game in there. Apple, the Mac, also had had some. So it’s kind of a goofy thing to stick a few free games in with the software. Bridge, we still don’t have good software for playing Bridge, but that will get solved.

Childhood Today vs. the Past

PATRICK COLLISON: Last question. Is it better or worse—so this is a book about your childhood and adolescence and, I guess, at least the first couple of years of Microsoft. Is it better or worse to be a kid today, growing up in the U.S. today than it was when you did in the ’60s?

And will it be better or worse in 20 years?

BILL GATES: Well, it’s certainly better today than it was in the past. It—

PATRICK COLLISON: And specifically when you were growing up?

BILL GATES: Yes. I mean, if you happen to be grown—go to Lakeside School like I did, okay, that was pretty good.

That’s better than the average today. But my childhood, because of luck and my parents, was substantially better than the average childhood today. It just had so many things that nurtured me and encouraged me, you know, friends, teachers, all of those things. But if you say on average, you know, being born in 1955 when I was, the—you know, we are so much better off. If you want to learn something today, they—you could just go on and learn anything.

I had to read the World Book, and it’s, you know, in this funny alphabetic form, and there’s no videos to really describe things. And—

PATRICK COLLISON: You know LLM to ask clarifying questions?

BILL GATES: Yes. And so it’s really ahistorical. It’s fine that people are worried about the problems we face, including how we shape AI and polarization.

And we’re less—we’re arguably less ready for a pandemic now than after the last one because of the divisiveness that’s come in around that and the way that’s being staffed. So it’s weird the things that we all wish would be better and the things that we worry about. But if anybody thinks it was better back in 1955 for women or people who are gay or people who got heart disease or cancer. I mean, it’s just insane. The big headline is people are living longer.

People are learning more. People are more literate. And so when you say 20 years from now, absolutely, I’ve got my footnotes, a nuclear war or a super bad bioterrorism event or not shaping AI properly or not sort of bringing society together a little bit around the polarization. Those four things, yes, the younger generation has to be very afraid of those things. And they and they and, I forgot.

Let me change. And they find they’re—they’ll actually, to some degree, exaggerate the likelihood and maybe the impact of some of those things in order to activate people to make sure we steer clear of those things. So it’s not an automatic thing. But because humans do worry about those things, and even though I can’t see the solutions to those things, if I could, believe me, I would provide those. Although in pandemics, it’s pretty clear what we need to do.

It’s a—that’s a political will problem.

PATRICK COLLISON: People should read the book to get the prescription.

BILL GATES: Yeah. I read—yeah. That’s my book that really didn’t sell well.

It was my pandemic book. The climate book sold better than I expected, but the pen—people were not interested in reading about. By the time my book came up, that was like, “No. We’re—we had enough of that topic,” which okay. It’s—it’s fine.

I’m not—I’m not complaining about that. So, you know, absent not solving some of these big problems, things are going to be so much better off. Alzheimer’s, obesity, we’ll have a cure for HIV. We will have gotten rid of polio, measles, malaria. The pace of innovation is greater today than ever.

And I’m lucky I still get to back incredibly smart people who are doing all of that work.

PATRICK COLLISON: Well, on that note, Bill, thank you very much.

BILL GATES: Thank you.

Closing Remarks

MODERATOR: Well, oh, well. All right.

Just take a moment and thank Bill and Patrick one more time, please. Two things strike me. There aren’t very many people on the planet that know how to use a microscope and a telescope with incredible skill. And I think Bill is one of those human beings that can see things at a fine grain but also at a distance. And his work and his life’s work in this chapter of his life, which was nicely presented in the book and a nice conversation today, is indicative of sort of the breadth of his skill.

It was 20 years ago when he was on stage with John Hennessy here, and they had a similar discussion. And lots has changed in 20 years. The second thing is something that I was struck by in a book that I read a long time ago, and that is—and it’s a quote attributed to Albert Einstein, and that is that creativity is the residue of wasted time. And he clearly wasted a lot of time. Again, well, thank you all for coming today.

We really appreciate your support. And hopefully, you had a good time. So thanks for coming.

Related Posts

- How to Teach Students to Write With AI, Not By It

- Why Simple PowerPoints Teach Better Than Flashy Ones

- Transcript: John Mearsheimer Addresses European Parliament on “Europe’s Bleak Future”

- How the AI Revolution Shapes Higher Education in an Uncertain World

- The Case For Making Art When The World Is On Fire: Amie McNee (Transcript)