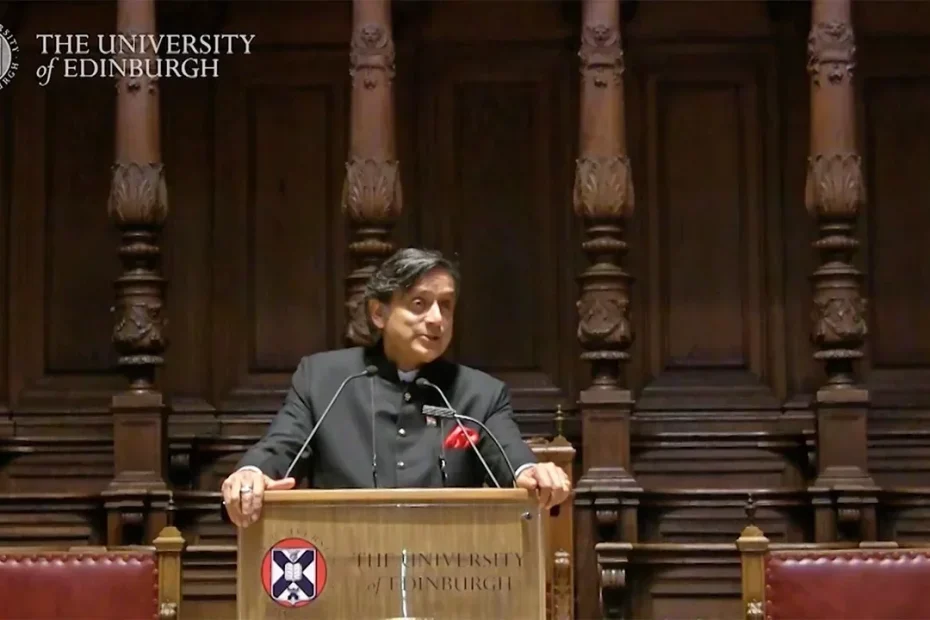

Read the full transcript of Dr. Shashi Tharoor’s lecture titled “Looking Back at the British Raj in India” at the University of Edinburg’s McEwan Hall on Monday 2 October – Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday – 2017.

Listen to the audio version here:

TRANSCRIPT:

Introduction

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: We have much to celebrate in the relationship between India and the University of Edinburgh. And I’m delighted that this year our speaker in this headline event on India Day is Dr. Shashi Tharoor. Dr. Tharoor is a globally recognized speaker and author on the economics and politics of India as well as on freedom of the press, human rights, Indian culture and international affairs. Dr. Tharoor is currently serving as a Member of Parliament in India, a role he has held since 2009.

Previously, he was Minister of State in the Government of India for External Affairs and for Human Resource Development. Dr. Tharoor also has an outstanding record of service internationally through his work for the United Nations between 1978 and 2007, where he rose to the rank of Undersecretary General for Communication and Public Information.

An acclaimed writer, he has authored sixteen bestselling works of fiction and non-fiction since 1981, all of which are centered on India and its history, culture, politics, society and foreign policy. He’s also the author of hundreds of columns and articles in publications such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time Magazine, Newsweek and The Times of India. His is a strong, clear and articulate voice and his analysis and the debate more generally about a fraught period of history are at the heart of many of my colleagues’ teaching programmes in the social sciences here at Edinburgh.

His talk today, Looking Back at the British Raj in India, will explore how the British Raj has shaped the narrative around India-UK relations.

Dr. Shashi Tharoor is one of those rare people who can be genuinely seen as a polymath. He has such outstanding credentials as a scholar, a politician, an international civil servant, a novelist and so much more. It’s a real honour and pleasure to welcome him to the lectern to deliver his talk today.

Dr. Tharoor’s Lecture

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: Thank you so much, Professor Meale and Principal Houche, distinguished members of the faculty, students, friends. I hope that covers everybody. Very good to be with you and in this magnificent hall that I haven’t stopped admiring since I stepped into it a few minutes ago.

This really is a wonderful setting to be able to speak about issues that go back as old as this building, I see. But I do want to acknowledge as Principal Ashe has just mentioned, the extraordinary connection of this university to India. The work of one of your early principals, one of his distinguished predecessors, William Robertson, in the late eighteenth century in writing one of the very first books about Indian commerce. The fact that the oldest Indian students association in the UK is yours, and that goes back a hundred and forty years. This is a remarkable legacy and it’s wonderful to be here and, in a small way, to participate in that legacy.

Looking back on the British Raj in India, at this time, which is of course the seventieth anniversary of India’s independence, is really about looking back at a tumultuous period of history on which, of course, there are various opinions. I have done so in my still relatively new book, “Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India.” And it’s a book which emerges unusually enough from a speech. I hadn’t really planned to write this book. I did do a PhD very many years ago the hard way, not the Shahrukh Khan way, if I might say so.

I know and like him a great deal. And don’t get me wrong. I think it’s a pleasure that he was here a couple of years before me. But just to say that I did the PhD the hard way, but then I went into the United Nations and have really not kept up with the academic rigor that would be required of somebody writing a work of serious history. But I was invited by the Oxford Union to participate in a debate on a topic the students said, which was “Britain owes reparations to her former colonies.”

The Origins of “Inglorious Empire”

And though I was never particularly keen on the idea of reparations for the simple reason that I think the damage done by colonialism was so immense that it is essentially unquantifiable. How do you put a value on the literally millions of lives lost, for example, just the thirty-five million Indians who died totally unnecessary deaths in British-created famines? And then you say, well, alright. So any sum of reparations that is payable would not be credible, and any sum that is credible would not be payable. So why bother with the reparations route at all?

But I agreed to speak nonetheless because I felt it might be a good opportunity to lay out some of the basics about British colonialism in India, that were in danger of being forgotten and eclipsed with a lot of the revisionist popular history that had reached the bestseller charts in the last decade and a half or so. So I spoke. And on the question of reparations, I said, well, look, since this is about reparations, a symbolic one pound a year for the next two hundred years would do it because what I’m really interested in is atonement, not money.

When I made the speech, it seemed to have an impact on the audience because we won the debate rather handily. So many members of the audience went into the yes lobby that the post-debate reception had to be delayed for half an hour. They were counting the results. It was very gratifying. But I forgot about it. And then three or four weeks later, the Oxford Union posted the debate or the individual speeches in the debate on YouTube, and my speech went viral. We suddenly had an enormous frenzy with some three million people downloading it in the first twenty-four hours alone.

And amid all the hubbub, the Speaker of Indian Parliament had some kind words to say, the Prime Minister of India, no less, said—and this is somebody who, after all, I’m a member of the opposition in parliament—he said this is an example of somebody saying the right thing at the right place, which, as you can imagine, set some of the pigeons in British chancelleries fluttering because he was two months away from his maiden visit to London. But anyway, there was all this excitement. My publisher rang me up and said, “Look, you’ve got to turn this into a book.” And I said, “Why bother? Surely, everyone knows this already.” And he said, “No. They don’t know this already because if they did, your speech wouldn’t have gone viral.” And that seemed to be irrefutable logic, and so I decided to write this book.

And this book, therefore, emerged from that speech, but it’s somewhat perhaps more thoughtfully considered, more structured, and certainly bears the imprint of considerably more research than a speech largely delivered off the cuff could have done.

The Central Argument

And what is the central argument I make about the British Raj? I state essentially that the British came to a country which was one of the richest countries in the world. In fact, in 1700, India was the single richest country in the world with a GDP that accounted for twenty-seven percent of global GDP. As late as 1800, India’s GDP was twenty-three percent of global GDP. These are figures established by the famous, now late, econometrician and historian, Angus Madison.

And a society which was a fairly sophisticated and thriving society, the world’s leading exporter of textiles for the preceding two thousand years, major country in shipbuilding, in steel making, a complex society of merchants, artisans, bankers, many thriving cities, urban developments. It came to this country, and in two hundred years of plunder, devastation, and loot, a Hindi word which the British took into their dictionaries as well as their habits. It reduced this country to a poster child for third world poverty. So that when the British left in 1947, this country was now not just poor, but ninety percent of its population was living below the poverty line. It left a country with a life expectancy of twenty-seven and a literacy rate below seventeen percent.

So the story of these two hundred years of devastation needed to be told and told whole and that’s what I’ve tried to do. But equally, I felt I had to take into account the various apologia for the empire that had been articulated by otherwise thoughtful historians like Professor Ferguson and others, more popular writers like Lawrence James and Andrew Roberts and so on, who argued that the British Empire was, in Neil Ferguson’s memorable words, “a jolly good thing” with a capital J, capital G, and a capital T. And that had laid the foundations for the globalization, from which India was so greatly benefiting at the time that he was writing.

So I decided therefore to take up the specific claims made for the benefits of empire and to refute them one by one. I can’t obviously give you all of that in the time available to us. I’ll try and give you a reasonably quick summary of the main points so that we can have an exchange in the Q&A to follow. And then if your curiosity is still not satisfied, do pick up the book, which I’ll be signing at the end of the talk, and which has something like thirty pages of endnotes, that point you to my sources for further clarification.

The British Conquest of India

Broadly, what did the British do? They came to this country and the East India Company, which in its charter, by the way, explicitly was given by the British queen the right to use force in pursuit of its economic aims, came to India. And the British has always have always had a great gift of timing.

The Mughal Empire, at that point was at its peak. There was a great deal of wealth about. The emperor Aurangzeb in 1700 had revenues that exceeded those of all the crowned heads of Europe put together. His revenues alone were greater than those of Louis the Fourteenth and Versailles—ten times greater, in fact. That’s how wealthy and opulent he was.

But in the early eighteenth century after Aurangzeb, the empire began to disintegrate. It took a couple of body blows from a pair of invasions, most famously or notoriously that of the Persian king, Nadir Shah, in 1713, who so completely looted and devastated the Mughal capital, Delhi, that it’s said that nobody in Persia had to pay any taxes for the next three years, so much were the riches that they had taken out of India.

And this weakened Mughal Empire, the various governors of the provinces around the country, had essentially then become, because of the central government’s weakness, potentates, semi-independent rulers in their own right, which meant that the British, as they began to establish themselves by force of arms, never had to take on the entire might of India, but rather could sort of expand gradually by defeating one prince after another, one Naval or Maharaja after another, and gradually spread the red stain of British rule across the subcontinent. This they did.

Deindustrialization of India

And what they did essentially then was to proceed to deindustrialize this economy. I’ll just give you a couple of examples. The textile industry was India’s great triumph because, going right back to the days of the Roman Empire, India was a world renowned exporter of textiles, particularly fine cottons, muslins, gauzes, linens. And there are accounts by Pliny the Elder of debates in the Roman senate in which senators decry that vast quantities of Roman gold were being sent off to India because of the taste of their womenfolk for these fine Indian cloths.

Not only that in the Roman Empire, but I found accounts in British, writings, English writings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of English shopkeepers trying to pass off shoddily made European cloth as “made in India” because “made in India” was what had the cachet of being highly desirable, high quality cloth, sought after by the aristocracy of Europe as well as, of course, of England. There were the Dhaka gauzes, for example, said to be as light as woven air, so fine that you could pull an entire sari through a ring.

And these wonderful textiles essentially could not be competed against. So the British proceeded to destroy them, smash the looms, drive the weavers out of employment. In one notorious incident, I’m careful to say one according to oral law. There were hundreds of such incidents, but they’ve not all been documented as British historians like to point out. But there is one that was documented by a contemporary Dutch observer.

In one notorious incident, the British chopped off the thumbs of the weavers so that even if the looms were rebuilt, they couldn’t weave again. And the textile industry was essentially destroyed. We had the first major urban centers in the world to be reduced in population, Moshidabad and Dhaka. The statistics show how these places lost people as the textile industry collapsed and the weavers were driven out of these cities, into a countryside that couldn’t support them. And of course, the British then imposed punitive duties and tariffs on the remaining cloth that Indians were exporting, essentially destroying the export industry.

The Economic Impact of British Rule in India

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: There were various other restrictions including on shipping and so on. And they lifted duties and tariffs or, since they controlled the ports, didn’t have any duties and tariffs on British cloth coming into India, thereby acquiring a vast captive market through force majeure. That was the textile story in short.

Shipbuilding had a similar story. India had two major shipbuilding industries, on the East Coast and the West. Indian wood, teak and mahogany in particular, were highly sought after and lasted much longer.

An average Indian ship lasted about twenty-five to twenty-six years of sailing on the high seas, whereas the average European ship made of fir or pine never lasted more than six or seven years. The craftsmanship was exceptional – I’ve made sure to quote British sources about the high quality of Indian craftsmanship.

The British initially said, “Well, this is wonderful. Why don’t we make our own ships here?” And they started making ships in India, but that suddenly meant large numbers of shipwrights, fitters and carpenters being thrown out of work in the London dockyards.

So the British parliament promptly passed an act that forbade ships made in India from plying the lucrative trade routes across to England and in international waters. That pretty much killed the Indian shipbuilding industry. I’m giving you short summaries. There are somewhat lengthier versions of all of this in the book.

The Destruction of Indian Steel Industry

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: India had invented an extraordinary steel making technology, called Wootz steel. The Europeans couldn’t pronounce that, so they called it Wootz steel, W-O-O-T-Z. You can look it up. But it wasn’t an East European word as it sounds from the spelling. It was a mangling of an Indian name. The technology was so highly sought after.

The Arabs came and learned it to make what was known as Damascus steel. And when the English soldiers first killed Indians in their early battles, they made sure to dismount and steal the Indian swords because the quality of the steel was so much superior to anything they could actually get in Europe.

Well, that industry was destroyed again with various restrictions on what could be made. Indians were simply not allowed to make steel under either the old technology or the new techniques that came into being in the mid-nineteenth century.

I do tell briefly the story of how in the late nineteenth century when the Indian industrialist, Jamsetji Tata, tried to manufacture steel through setting up a modern steel factory, he ran into such implacable British opposition that he spent about twenty years running around trying to get the various permissions required, being denied throughout at every stage. Finally, he did succeed in getting the permission, but by that time, he was so old that the first steel ingots were produced under the stewardship of his son.

But anyway, at that time, a senior imperial official, the then chairman of the railway board, sneered that he would personally eat every ounce of steel that an Indian was capable of producing. I only regret the gentleman didn’t live long enough to see the descendants of Jamsetji Tata buy the remnants of British steel when they bought Corus a few years ago. Might have given him a bad case of indigestion.

I mention these not to belabor the point, but just to say that India was systematically deindustrialized. Of course, the counterargument that is often made is, “Look, it’s not our fault. Your textiles were all handloom. Your steel was an old-fashioned technology. Your shipbuilding was all wood. You just missed the bus for the industrial revolution.”

Well, I’m sorry. We missed the bus because you threw us under its wheels.

The fact is that when you are the world leaders in the prevailing technology of the time, you are able to do well enough to buy whatever new technology is invented thereafter. And there is no question that India would have been able, as other countries did, to buy into the industrial revolution had it been free and allowed to do so. That’s on the deindustrialization argument.

Rapacious Taxation Under British Rule

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: But what else? You had rapacious taxation. So rapacious that contemporary accounts – and in all fairness, the historical record has been meticulously maintained by the British – you’ve got House of Commons testimony in repeated hearings in the late eighteenth century all the way up to mid-nineteenth century, in which you can read detailed accounts of how the East India Company’s officials behaved.

And by the way, don’t buy the myth that this was just a corporation ruling India and not Britain. It was very much, shall we say, a mask for the British government. First of all, from 1774 onwards, East India Company operated under a board of supervision of the houses of parliament.

Secondly, some 28 percent of the shareholders of East India Company were MPs. And thirdly, all the top officials were not only part of the British establishment but were appointed with the knowledge and consent of the British government. So for example, Lord Cornwallis, after surrendering to George Washington in Yorktown, was deployed to Bengal to be governor of Bengal. So there’s no real distance between British colonial imperial governmental authority and the so-called corporate authority of East India Company. It was British rule by another form, wearing another mask.

So anyway, you can read the accounts of their taxation policies, for example. Not only was their taxation more onerous than that of the most rapacious of those who preceded them – so onerous, in fact, that there are innumerable accounts from British sources of Indian peasants fleeing the lands controlled by the British into the still remaining Indian-ruled states where they’d lead a more decent life.

But what was worse was the taxation was exacted pitilessly with ruthless means of enforcement, including torture, as well as with absolutely no exceptions made because, of course, the British did everything by the book.

Whereas Indian rulers could be pretty nasty too and levy taxes on people, if there was a drought, for example, or if there was a death in the peasant’s family or a wedding in the peasant’s family, what would happen is that the taxes would be reduced or waived or delayed or postponed. That kind of flexibility was always implicit in Indian culture.

There was no room for that kind of flexibility in British culture. Everything had to be literally by the book. You will pay 85 percent of your crop as tax or whatever, and indeed the rates were often as high as that. And if you didn’t, some of the tortures and exactions were so severe that when they were read out in the House of Commons – I come to what was done to people who couldn’t pay the tax – in one famous incident, the playwright Sheridan’s wife (Sheridan was a member of the House of Commons) swooned in the gallery on hearing how horrible her countrymen were in India and had to be carried out bodily. And this was reported in the papers at the time. So you’re looking at some pretty awful behavior.

Famines Under British Rule

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: But taxation was just one aspect of it. Look, for example, at famines.

Now India had had droughts before, but people had rallied around to save those who were starving or help prevent them from starving or give them charity if they were starving. A long tradition of helping those who needed food. And this is why, for example, for three thousand recorded years of Indian history before the British came, you have accounts of monks, whether Buddhist, Jain, or Hindu monks going from door to door with a begging bowl, asking for food, and routinely being fed. This was the normal custom in the culture.

But what happened in this particular instance was that when the British came, they operated, whether in India or indeed in Ireland, on four sets of principles.

The first was do not give charity because charity encourages idleness. So there was simply no question of helping people just like that. You all remember Charles Dickens’ work houses for the poor. You had to work for your money. There was no charity given.

Second principle was the free market must prevail. So if you’re buying grain to fill the bread baskets of London from places where there is a drought and there isn’t enough grain to go around, and by your buying the grain, you’re driving up the price of the scarce grain there is beyond the capacity of those who need it, who are starving, to buy it, well, tough. That’s the law of the market. You buy the grain and take it off to London.

Third principle was the Malthusian one. That is, as Malthus said, that if the land cannot sustain the population that’s trying to live off it, then people must die. That’s how the natural population balance will be reasserted. Let them die.

And the fourth principle was Victorian fiscal prudence. That is, do not spend money you haven’t budgeted for and never budget for a famine.

So the result was an appalling situation when in these two hundred years of British rule, you have recorded evidence for at least thirty-five million people dying systematically as a result of British policy.

And it bookends the entire British Raj. In the first famous famine of the British Raj, the Bengal famine of the 1770s, one-third of the entire population of the province – six million people – died. In the last major famine of the British Raj, which was the 1943-44 Great Bengal famine, 4.3 million people died entirely because of decisions taken by a certain Winston Churchill.

Now when you look at this and you look at the record in between, it is, as you can imagine, Prussia Dismay. What’s striking is, I’m sure the English people in this audience are saying, “But how could we let that happen?” Well, initially, these principles applied. In fact, these principles applied, as I said, across the board.

So in Ireland, during the potato blight of the 1840s, this is precisely what occurred. The Irish died because these same four principles were applied to them, except that many Irish were able to hop onto boats and sail off to New York, and Indians didn’t have that option. They just had to stay in India and die. That was essentially the alternative.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the enlightenment had progressed sufficiently. The British people had a public opinion, had a conscience, had a free press. There are articles about this, and people were appalled to read accounts, dispatches from India, even if it became weeks afterwards of people dying.

Lord Salisbury, the secretary of state for India, later famous prime minister, talked about having sleepless nights because of the two million people who died on his watch in the Orissa famine of 1866 because he had agreed that these four principles should be applied and aid should not be given.

Indeed, not just that aid should not be given, but I have recorded in my book one instance of some poor, kindhearted gentleman, a Mr. Macmillan, perhaps a good Scot, who tried to help a person starving to death and was sternly warned by the British authorities on pain of deportation that he must stop offering charity because it was against British policy. So this is as late as the 1860s.

But this had begun to create a bit of a backlash in British public opinion. So in the 1870s, they decided, alright. We still won’t give charity, but we’ll set up work camps so that Indians can work for food instead of starving to death.

And when they did that, as Professor Mike Davis has recorded in his marvelously painful book, “Late Victorian Holocaust,” the rations given to the inhabitants of these work camps, people who had to work and toil in order to keep body and soul together, the rations given was less than half of what Hitler’s Nazis gave the inmates of the Buchenwald concentration camp before sending them off to the gas chambers. So that was British colonialism at its peak.

The Great Bengal Famine of 1943-44

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: And what about the Great Bengal famine? I should tell the story if for no other reason than that it will shock some of you.

The Great Bengal famine occurred because indeed there was a drought in Bengal and supplies of grain were not available. People started starving. But Churchill had ordered that food should be procured from Bengal and shipped off to Europe, not just to aid the war effort. In fact, not to aid the war effort immediately, but to increase reserve stocks in Europe in the event of a future possible invasion of Greece and Yugoslavia.

So, grain was sent off from Bengal. Prices became unaffordable. People started dying. The British official, this is the 1940s after all, wrote to the prime minister, Mr. Churchill, saying, your decisions are causing people to die.

Churchill’s response was, “I hate Indians. They’re a beastly people with a beastly religion. It’s all their fault anyway for breeding like rabbits.” These are exact quotes, by the way, word for word.

More people continue to die. The death tolls started mounting. Ships laden with wheat from Australia were docking at Calcutta port, and the British officials wanted to disembark the wheat to save lives. Churchill said no. The ships would sail on to Europe for these buffer stocks, these reserve stocks. More people died. The figure kept mounting.

It reached 4.3 million. When conscience-stricken British officials in Calcutta sent a memorandum to the prime minister in Downing Street about the consequences of his actions that literally millions were dying, Churchill wrote on the margin of the file, “Why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?”

And this is the man whom the British expect us to hail as some sort of apostle of freedom and democracy. As you can imagine, the very thought sticks in my craw.

So that is the British record on famines.

Looking Back at the British Raj in India

DR. SHASHI THAROOR:

And there’s more in the book, but I won’t belabor too many points because I do want to leave time for an exchange with you. That’s the best part of being in a university. But let me talk briefly about some of the arguments that are made for what the British did for India rather than to India.

One example that is often cited is that India was unified because of the British, There wouldn’t be an India today except for British rule. First of all, the very premise is laughable because there had been an idea of India, Bharat Varsha, the land from the Himalayas to the oceans, going back to the Rigveda, which is about fifteen hundred BC, a good three thousand years or more before the British got there.

What is more important was that successive Indian rulers had tried to consolidate the entire territory of today’s India and indeed more, including what’s today Pakistan and Afghanistan in their empires, and two had pretty much succeeded. The Maurya Empire under Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka controlled about ninety percent of the entire subcontinent, in the fourth century and third century before Christ. And the Mughals under Akbar and up to Aurangzeb in the sixteenth, seventeenth centuries controlled about ninety-five percent of the subcontinent at its peak. So the desire to control all of India as one preceded the British by a long chalk.

Secondly, there was always a sense of civilizational unity in India well before the British. There was, for example, Adi Shankara Shankaracharya from my state of Kerala in the extreme south traveling all the way to Kashmir in the north, to Dwarka in the west, to Puri in the east, and establishing his temples, his seats of religious learning, his mutts as they’re called.

And many, many other examples. The Harvard scholar Diana Eck writes of the sacred geography of India knit together, she says, by countless tracts of pilgrimage. And if that seems a purely Hindu idea, let me mention that the Muslims felt the same way. Maulana Azad has written of how Indian Muslims going on the Hajj were received by and greeted by other Muslims, Arabs in particular, as all being from a common civilizational space. Whether they were Pattans from the northwest or Tamils from the southeast, these Indian Muslims were all called as Hindis, people from Al Hind.

So the world saw India as one before the British can claim credit for having knitted together. What the British actually did was to divide it because what they did was to essentially create the seeds of what became the destruction of this three thousand year old idea of India in a policy that was explicitly minuted.

The British Policy of Divide and Rule

Wonderful thing, as I said, about British oppression is all these things are always written down. Lord Elphinson, after seeing Hindu and Muslim soldiers fighting side by side and under each other’s command under the banner of the infeasible Mughal monarch, against the foreign oppressor, in the so-called mutiny of eighteen fifty-seven, the Indian revolt, he wrote a memo in eighteen fifty-eight saying, “divide et impera was the old Roman maxim, and it shall be ours.” Of course, all of you good scholars in Edinburgh know it wasn’t just a Roman maxim.

It goes before the Romans to the Macedonians. Philip the second of Macedonia came up with the “divide et impera” phrase. But the British were the first to apply it in India, and they did it very systematically. Divide and rule became their ruling credo, and they decided that the basis of divide and rule must be religious, and there must be a conscious, deliberate attempt made to foment separate religious consciousness amongst the communities of India to prevent united opposition to them.

They did this systematically. They did it, as I’ve documented in great detail in the book, sometimes through intimidation, sometimes through granting of favors, and sometimes through outright bribery. One of the more amusing episodes was how, when they partitioned Bengal in nineteen-five to create a Muslim majority province in the eastern part of Bengal, the Muslim nobleman, Nawab Abdhaka, who was an Oxonian, absolutely refused and said, “certainly not. This is a beastly idea. I shan’t stand for it.” So they slipped him a hundred thousand pounds, and he changed his tune.

That was the way in which these ideas were advanced. They went right through. When the British grudgingly granted very limited franchise in elections for a limited number of people to a limited number of seats in the viceroy’s council and in provinces, so limited, in fact, that only one out of every two hundred and fifty Indians had the vote, they still did so on the basis of separate, religiously separate communal electorates. While England would never have thought of, say, giving the good Jews of Golders Green their own electoral list, in India, Muslims could only vote for Muslim candidates for seats reserved for Muslims. So this is a way of ensuring that people thought of their interests in religious grounds and thought of their political identity in religious grounds.

When the Indian National Congress established in eighteen eighty-five tried to represent all Indians—in fact, if you look at a list of their first twenty odd presidents, first twenty years, you’ll find Christians, Parsis, Muslims, and Hindus all presiding over the Indian National Congress. And these were largely genteel, Anglophile lawyers who were writing decorous petitions seeking the rights of Englishmen for the Indians. Nonetheless, what the British did was to actually set up and encourage the setting up of a rival body, the Muslim League, organized on religious lines rather than co-opting the one body there was if they were serious about any notions of responsible self-government.

I’ve been given the signal that it’s time for me to begin to start wrapping up. So I won’t go into the other examples until we get to our Q&A.

The Myth of British Benefits to India

But if any of you is interested in, for example, some of the other alleged benefits of British rule, I will give one more. The fact is that in every single case, anything you can point to that India can claim as a benefit, it is without exception something brought into India in order to serve British interests, enhance British profits, or improve British control. No other purpose. There is not one thing that was actually given to India to benefit Indians, and I’m very happy to explain that in more detail when the time comes up.

I’ll give you one example which is too often cited to be left out of this talk, and that’s the railways. One of things I always find people falling back upon is, “well, at least we gave them the railways.”

Well, yes, and you couldn’t really take all the tracks out of the ground, could you, and take them off? But, anyway, the fact is that the railways were brought in explicitly for two purposes. One was to extract resources from the hinterland and ship them to the ports to take them off to England, and the second was to send troops into the interior to quell any popular unrest.

But what’s more striking is that even the building of the railways was a gigantic colonial scam. What happened was that the British guaranteed to investors in the Indian railways double the dividends, double the profits that they could make on any other British government investment at that time.

In other words, you got double the rate of return on the highest returning British government securities. It’s the most profitable thing you can invest money in within the eighteen forties and eighteen seventies was the Indian railways. So you got the British making big profits, and all the costs were paid for by Indian taxpayers without exception. It was described at the time as “private profit and public risk,” except that the private profit was all British, and the public risk was all Indian.

So lavishly did they spend on this because they were making money out of it at every stage, that one mile of British Indian railway cost nine times what the same mile was costing at the same time in the US or Canada. That was how extortionate even the construction of railways was.

And as I’ve described in the book in greater detail than I have time for now, it was also run as a completely racist enterprise right down to the fact that when passenger wagons were eventually added, with wooden slats for benches for the Indians to sit and travel on, the Indian passengers paid the highest passenger rates of any railway in the world, whereas the British companies paid the lowest freight rates of any railways in the world to ship their goods on these railways.

It was only after independence that India reversed this pattern and made it now the cheapest form of railway travel in the world anywhere, though unfortunately also amongst the most expensive ways of shipping freight.

The Need for Atonement

But let me end by answering a question that many ask. What’s the point of all this now? It’s been seventy years. They’re gone. You know, what do you want out of this? And as I said, I’m not really looking for reparations, but I am looking for atonement. I think there is a moral debt that needs to be paid far more than a financial one.

And to my mind, that can take a couple of fairly obvious forms. The first is, as I say to my British friends, for God’s sake, teach unvarnished colonial history in your schools. It is shocking that you can do A-levels in history in England today without learning a line of colonial history. The week my book came out in India, by coincidence, there was an article by a Pakistani journalist in The Guardian about raising two children in the best and most expensive public schools in London who’d both done A-levels in history and hadn’t heard a thing about colonial history. That’s got to change.

And I think that must really change in the interest of Britain as well. I recount, for example, a passage in the book about Horace Walpole, taking a carriage down a London street and describing building after building that has been built by Indian money. He called London “the sinkhole of Indian wealth.” Nobody in London today has any idea that so much of London’s grand mansions were built by money extracted from the colonies.

All you’ve got now is either historical amnesia, no teaching of history—I mean, the schools, I know you can study Indian history in universities if that’s your subject, but obviously, for a lot of people, it won’t be. But you don’t actually learn all this there. And so there’s no sense of the colonial connectivity.

I remember being struck by a wonderful protest by a number of black and brown Britons objecting to all the anti-immigrant language in the political space a few years ago. And the photograph I saw in the newspapers was of these black and brown people holding up placards in London that read, “We are here because you were there.” And it’s shocking. It was surprising to me that the Britons actually needed to be reminded of that.

The other thing worth talking about is the fact that in a country overflowing with museums—I mean, London is a capital littered with museums, one thieves market after another. I mean, every single thing practically in all these museums was purloined from some colony over the last few centuries.

There’s even an Imperial War Museum, but there is no museum to colonialism. There is nothing where a schoolchild or a tourist or a visitor can go and see the whole story of what Britain did and gained from the various parts of the world it ruled. As I said in the Oxford debate, yes, the sun never set on the British Empire because even God couldn’t trust the Englishman in the dark. But that’s because they were there helping themselves to everything they could find in all these places around the world. And it would be good if a museum were constructed to show this.

It’d be good if there were monuments. It’s striking that in the heart of London, there is a statue to the animals that fought with the allies in the two World Wars, but there is no statue to the Indian soldiers who fought in the two World Wars. One point three million Indians fought in the First World War, one point seven million in the Second World War. Over a hundred and fifty thousand Indians perished in defense of Britain’s freedoms. And no statue.

I mean, it’s really quite remarkable actually when you think about it. I think in the First World War, more Victoria Crosses were won by Indians than by British soldiers. There was the famous Battle of Ypres, which stopped the German advance at the very beginning of the war when Britain was otherwise unprepared to resist the advance. Here you have Indian soldiers sailing to Egypt who were suddenly diverted onto Belgium because war had been declared and who were able to stop the German advance in Ypres, Neuve Chapelle. You’ve got all these stories that are essentially unknown in Britain today.

And I think, again, that needs to be told. But it’s not just about remembering. The remembering is important. I’m always saying to young Indians, if you don’t know where you’ve come from, how will you appreciate where you’re going? And I think that’s true too for British young people.

But it’s something more, and that’s perhaps the difficult part with which I’ll conclude. I think that one essential form of atonement is an apology. Now I know many Britons will say, but why should we apologize? We haven’t done anything to the Indians. What’s more, there’s nobody really alive today who profited much from the British Raj who did anything to the Indians.

The Legacy of British Colonialism in India

And in any case, there’s nobody alive in India today who directly suffered at the point of a British bayonet or whatever. So why should we apologize? To which I will point to two counterexamples. First, the German chancellor Willy Brandt sinking to his knees in the Warsaw ghetto in the nineteen seventies in apology for what the German Nazis had done to the Polish Jews. Now Willy Brandt was a social democrat. People like him had been persecuted by the Nazis. He was completely innocent of any taint of Nazi wrongdoing. But he felt as the embodiment of the German state that it’s never too late to do the right thing, that he needed to apologize on behalf of the German people.

And the second example I would point to is from somebody you honored in this university just a year or two ago, Justin Trudeau. The prime minister of Canada apologized to the people of India in the Canadian parliament for one incident, the so-called Komagata Maru incident, where the Japanese ship, the Komagata Maru, laden with Indian refugees fleeing British rule, was turned away at gunpoint from the port of Vancouver, and pretty much everybody on board later perished either on the high seas or at British hands when they landed.

That’s something that Britain has never done. And I have the perfect occasion to suggest because on the thirteenth of April two thousand and nineteen, you will have the centenary of the single worst atrocity of the British Raj in India. Not the worst in terms of numbers of people killed. The British killed some hundred thousand people in Delhi alone in eighteen fifty-seven and fifty-eight in putting down the so-called mutiny.

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

But in terms of everything that happened around it—and I’ll take five minutes just to tell you that story, and I’ll end and take your questions. What the British did was, as I said, India supported them in the First World War. And they said that they would accept the support, which, by the way, wasn’t just the one point three million soldiers. It was vast sums of money from a starving country, money paid for not just by the treasuries of the Maharajas, but by poor Indian taxpayers at the time when the Spanish flu had taken a larger toll in India than any other country because our public health under British rule was in such bad shape. But India also supplied food, clothing, uniforms, carts, pack animals, and even rail lines ripped out of the ground to go and aid the war effort in Europe and Mesopotamia.

And they did so because the British promised them responsible self-governance at the end of the war. And Indian leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi, who called for support for the war effort, assumed this meant dominion status, which was what the so-called white Commonwealth countries like Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa enjoyed at the time.

Well, Perfidious Albion broke its word, won the war, and didn’t keep its promise. Not only no responsible self-government, but in fact, Britain chose to reimpose the wartime era prohibitions on freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, freedom of speech, and so on. Whereupon protests immediately broke out across British India, the British responded by declaring martial law.

They didn’t use the word, but they sent British generals and soldiers to quell unrest throughout British India. And a man called Brigadier General Reginald Dyer showed up in the Punjab town of Amritsar to keep the peace there, declared that people could not assemble in groups of more than five. But he didn’t realize that he’d overlooked that this was the Punjabi Spring Festival of Baisakhi. And in fact, large numbers of people, both from Amritsar and from the surrounding villages, had gathered to commemorate Baisakhi in a walled garden, Jallianwala Bagh, with just one gate, one entrance to it. And these were men, women, and children.

In fact, large numbers of women and children. There was song and dance and speechifying, and maybe some of the speeches were hostile to Britain, but there certainly wasn’t a single weapon in sight. Dyer heard these people had gathered. He marched there with his soldiers, didn’t ask them why they were there, did not order them to disperse, did not even fire a warning shot. He just ordered his soldiers to assemble at the gates, the sole entrance and exit to the garden, and to open fire on these unarmed civilians.

One thousand six hundred and fifty bullets were fired, and Dyer proudly boasted not a single bullet was wasted as the wailing, screaming crowd rushed to the exits. As Dyer proudly told the inquiry commission later, “They made easier targets. That’s why I put my soldiers at the gate. Every bullet struck somebody.” The British acknowledged three hundred and seventy-nine dead.

The Indians claim the figure was over a thousand, but certainly, the bullet marks still stand. It was a horrendous massacre. But worse was to follow. Not only were these people killed, others deeply wounded and maimed, but Dyer barricaded the gates and left the dead, the dying, and the wounded to rot for twenty-four hours in the hot April sun. Those still alive were wailing pitifully for water, and their families standing at the gate couldn’t go in and help them.

Dyer ordered Indians to crawl on their bellies on a side lane. And if they so much as lifted their heads, their heads were bashed in by British staves. After all this, as you can imagine, there was an uproar. There was a commission inquiry. The House of Commons censured him.

The House of Lords, however, not only exonerated him but praised him. That flatulent voice of Victorian imperialism, Rudyard Kipling, called him “the man who saved India.” A collection was raised for him amongst the British in India and in London, and the princely sum in today’s money of a quarter of a million pounds was given to him together with a bejeweled sword.

This entire package of events—the ingratitude for the support in the war, the betrayal of promises, the cruelty of the massacre, the indifference to Indian suffering afterwards, the racism that accompanied it, and then the self-justification and exoneration of the man—all of this put together makes Jallianwala Bagh the single worst atrocity of the British Raj in India.

Now can you imagine if on the centenary of that event, a member of the British royal family, because everything after all was done in the name of the crown, and no politician from Britain is likely to do this, but if a member of the British royal family were to come to Amritsar and ideally, like Willie Brandt, sink to their knees and beg forgiveness or express remorse and seek or even apologize for the horrendous wrong that was done in that incident a hundred years earlier on that spot.

And by extension for all the wrongs of two hundred years of British rule, think what an extraordinary message that would send and what a cleansing effect it would have on the indelible stain of two hundred years of British colonialism in India. I rest my case. Thank you very much. I’ll take your questions.

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: And, what we’d like to do is take your questions one by one. And, as you ask your questions, please keep your questions as questions. Identify yourself and your affiliation. Thank you very much. Person? There’s a mic coming to you.

Q&A Session

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Good afternoon, Mr. Tharoor. My name is Usama Kamar, and I’m from Pakistan. You’ve argued time and again that Britain has a moral debt to pay reparations to India. But year nineteen forty-eight, RBI owed seventy-five crore rupees to Pakistan, which Gandhi, whose birthday is today, went on a hunger strike for, and only the first installment of that has been paid by India till date, don’t you think that India is actually following the footsteps of its colonizers right now?

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: Well, in fact, as you know, Gandhiji thought that the entire amount ought to be paid, and that was the theme of his last hunger strike. But as you probably also know, Nehru and Patel did agree and did pay the amount. So I’m a little curious as to where you get the impression that the full amount is not paid, but no doubt we both have to check our sources. To the best of my knowledge, it was all paid in nineteen forty-eight. Fifty-five crores was the exact amount.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Hello. My name is Sonali Misra. I’m from Delhi, India. And I have this question. What is your view regarding the postcolonial mindset with regards to the English language? To give a bit of context, I studied English literature at the Top Arts College of India, Lady Shriram. And I’m over here studying creative writing in English because my ultimate aim is to be a published author in the English language, which sadly, I’m now most comfortable with as opposed to Hindi, which is my mother tongue. So what is your view regarding it?

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: Well, it’s a very interesting question because, of course, we’re both in the same boat, and I’ve just addressed you in English. So, I’m not quite sure that any of us can get off the hook. To begin with, the British had no intention of teaching English to the entire Indian masses. That was simply not their plan. In fact, they had no intention of spending that kind of money to begin with on Indian education.

Will Durant, the American historian visiting India as late as nineteen thirty, was appalled to discover that the entire expenditure of the British government in India on education from the lowest levels to the highest university amounted to less than half the high school budget of the state of New York. So it really—which had one-tenth the population. So very clearly, the British are not interested in massive education. But what they did want was two things. They wanted to create a small class of Indians who would serve as interpreters between them and the masses they ruled.

Lord Macaulay, in his famous minute, his notorious minute on education in eighteen thirty-five, famously said that we need to create a class of people, “Indians in blood and color, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect,” quote, unquote. Now this objective was to be met by educating just enough Indians to serve British purposes and giving them just enough education so it wouldn’t create any trouble for the British.

Now the fact is that as it turns out, the Indians decided to take this language that the English had brought and to use it for subversion purposes. They learned English to explore new ideas, ideas that went perhaps beyond the ones the British would have intended them to acquire and to use them for purposes beyond that of facilitating British rule in India, but rather to actually explore ideas of their own freedom and autonomy that led eventually to calls for home rule and then for independence.

It’s striking, for example, that English became the principal language of Indian nationalism. Nehru wrote the Discovery of India in English. Jinnah made all his speeches in English. It’s the language in which he was most comfortable. So it is a paradox that this happened. But the second thing the British tried to achieve with the introduction of English was what one might call the colonization of the mind.

And that is, for example, the subject that you seem to have studied, English literature, was not taught anywhere in the world. It was invented to be taught to Indians. Professor Gauri Viswanathan at Columbia University has an entire thesis about how the study of English literature as an academic discipline was created as an instrument of colonial subjugation. Not just subjugation, of overawing the subject, you know, to make people feel that this is this great land that produced—Macaulay had notoriously said that the entire learning in every single books of India and Arabia are not worth a single shelf of British books. That’s essentially the approach they had.

And so that is something we have still not overcome. Those of us who went to school in India in the English language learned our Shakespeare but didn’t read Kalidasa. We may have, depending on the schools we went to, become familiar with the tales of the Iliad and the Odyssey, but not of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. You have to find those out at home. So you really have a situation in which that aspect of colonization of the mind, I’m afraid, has continued.

And it’s going to be something that each of us will have to overcome in our own ways. Not in any way to reject the extraordinary opportunities for learning and discovery that the English language has given us over the decades. And indeed, in today’s world, in the globalized world of today, English is a language of opportunity, of advancement, of employment, and so on. So I’m not at all anxious to move away from English. But for us to be able to use the language as, say, a Nehru or a Jinnah or a Dadabhai Naoroji did without letting our minds be colonized by it, to see the language as something, as a tool, an instrument for our thoughts, for our ideas, a vehicle to the destination we want to go and not where those who invented the language wish to take us.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Good afternoon, Doctor Tharoor. My name is Abhishek Takaja, and I’m from Bhopal in India, and I’m a final year politics student. I just wanted to take your views on some of the social reparations that the British objected to us, especially the fact that there was a very great limitation in free press and ironically, in democracy, which the Allies were fighting in both the World Wars. But what I particularly want to get your views on is the fact that similar depredations, especially socially, occur in India right now.

Freedom of the Press and Current Challenges in India

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: I’m not sure I caught every word. The acoustics aren’t terribly brilliant.

You wanted me to speak about particularly freedom of the press. Is that the point? Have I missed the example?

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Yes. So the freedom of the press and the social deprivations that the government of India has been subjecting, especially taking examples like the lynching of Indians…

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: You’re referring to today’s India and the events that are going on?

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Yes. Absolutely.

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: Well, as you know, I’m a member of the opposition, and I have spoken out very loudly and very vociferously against much of this. There’s no question in my mind that… they just turned up the volume on your mic as well.

Thank you, whoever did that. The fact is that we are witnessing some very dangerous tendencies in India, none of which can be directly attributed to the government other than the fact that the government has created the opportunity for unleashing a number of very unhealthy forces in our society, which it either appears to condone or not sufficiently curb.

Obviously, the government claims it’s not behind the so-called cow vigilantism that we have seen in the last couple of years. They claim that anybody who conducts a mob lynching will be subject to the rule of law. But in practice, practically no one has been convicted for any of these heinous crimes and murders.

To my mind, the frustration we have today is the change in attitude. I’ll give you two examples. There’s a horrendous story of Muhammad Aklak, father of a serving Indian Air Force soldier, who is attacked by a mob outside his house on the grounds that a bag of meat he’s carrying is actually beef. The man is beaten to death. The mob bursts into his house, breaks open his door, destroys the door of his fridge, takes out the meat in it, and rushes to the police station with it.

And instead of being arrested for murder, they’re let go while the police send the meat off to the lab to see if it was beef. I mean, is this the country that India is supposed to be about? As it turned out, it wasn’t beef. But even if it was, is that grounds to allow a mob to murder an innocent human being?

This atmosphere that has been allowed to prevail in parts of the country under the rule of our present government is something that is completely foreign to the essence of India. This is not the way we’ve lived for millennia. The last thing I want to see happening to my country is for it to turn into a Hindu Pakistan, with all reference to the Pakistanis here, who have their own battles to fight at home.

So the short answer is, if that was your question, then of course, I sympathize with you. Gauri Lankesh, one of the last things she did before she was shot was to retweet a tweet of mine in which I had shown a group of Kerala nuns performing an Onam Thiruvanam dance and talked about this being what Kerala’s pluralism and secularism is all about. She had talked about that in her Facebook post, and a couple of hours later, was shot.

I feel her loss very keenly despite never having known her as a person. This is, to my mind, a very dangerous indication of the kinds of forces that have been unleashed by our government’s refusal to take stern action.

Congress and the Jallianwala Bagh Incident

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Thank you very much. I’m Nandini. I’m from Calcutta, but I have adopted Edinburgh as my second city.

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: If you can barely be away from Calcutta… I remember the poet Pratish Nandi’s famous line, “If you must exile me, Calcutta, blind my eyes before I go.” I don’t want that to happen to you.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: It has happened. But my humble question is, when the Jallianwala Bagh incident was happening, Gandhi was there very much. And Congress was a powerful force in India.

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: No. It was a nationalist movement. It wasn’t in power.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: I didn’t say they were in power. Of course not. I only said they were a powerful force. So my humble question is, when these kinds of incidents were happening—you only mentioned about one—what was the stand of Congress as a forceful power in India? And just today, I was writing a post on Gandhi, whom I love very much, who grew and developed himself, and changed his policies throughout his career. But at that time, when Jallianwala Bagh was happening, what was his stance? And what was Congress’s?

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: I get your question. It was Congress that actually created the uproar that resulted eventually in Dyer being cashiered from the army. Congress refused to accept the findings of the British. They sent their own commission of inquiry, including a young Jawaharlal Nehru to Jallianwala Bagh. Nehru personally counted every single bullet hole on the wall.

They challenged the official account. They demanded action against Dyer. It was the Congress that stirred up a huge nationalist frenzy around the country on this incident, and it had a profound effect on a lot of people.

In many ways, it made Gandhi abandon the path of cooperation with the British. He would never again call on Indians to support the British war effort. In the First World War and in the Boer War before that, he had asked to support the British. In the Second World War, he called the British to “quit India, leave India to God or to anarchy,” as he said.

So it had a transformative effect. Sir Rabindranath Tagore returned his knighthood. This was a huge event, no question, for Indians at that time, and the Congress was very much in the forefront of it.

Forgive But Don’t Forget

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Thank you for the speech. My name is Manish. I used to study economics at the university. I graduated last year. So my question is, and I’ll quote one of your writings from “The Great Indian Novel”: “India is a highly developed civilization, which is in an advanced state of decay.” I mean, I might have missed a few words there, but do you think—and I get where this, or at least part of the decay comes from after your speech—do you think we’re doing enough today to undo the decay?

DR. SHASHI THAROOR: Well, firstly, that line is the privilege of the satirist. It’s from the opening paragraph of a satirical novel. So you do realize that one is allowed to poke fun in that process.

One could argue that we already are doing a great deal. The book was published in 1989. In 1991, our liberalization started. We took steps to actually overcome the decay. And I think literally in everything from the gleaming new airports to some of the gleaming new policies that have been instituted in the last twenty-five years or so, arguably, that sentence could not be written with the same sort of impact today as it would have had at that time when it was manifestly visibly true everywhere around.

But if we’re to say, “get where this is coming from,” my speech was not so much about that. My speech was essentially about how we are very much a forgive-and-forget culture, aren’t we? And I’m saying to the Indians, forgive. By all means, forgive. You must forgive, because not forgiving is bad for you. Nurturing hatred and bitterness actually hurts the hater far more than the hated.

But I’m saying forgive, but don’t forget. I just want people to remember. You can remember the past, embrace the past, but leave it in the past. I am not asking for this to come in, for example, and affect our relationship with Britain today. I think that today’s Britain and India are two sovereign equal nations. We don’t need to have a chip on the shoulder about each other.

We have a mutual language we can talk to each other in. Our economies are roughly the same size. So this is not about today’s India-British relations. I think we can leave that behind where it was, but we need to know. Just as every individual would like to know a little bit about their parents, where they came from, maybe their grandparents, a society should know about its past.

It’s part of who we are today, what we were before, and that’s the reason. So this speech and this book is not about that idea. It’s merely about, let’s forgive, but let’s not forget.

Related Posts

- How to Teach Students to Write With AI, Not By It

- Why Simple PowerPoints Teach Better Than Flashy Ones

- Transcript: John Mearsheimer Addresses European Parliament on “Europe’s Bleak Future”

- How the AI Revolution Shapes Higher Education in an Uncertain World

- The Case For Making Art When The World Is On Fire: Amie McNee (Transcript)