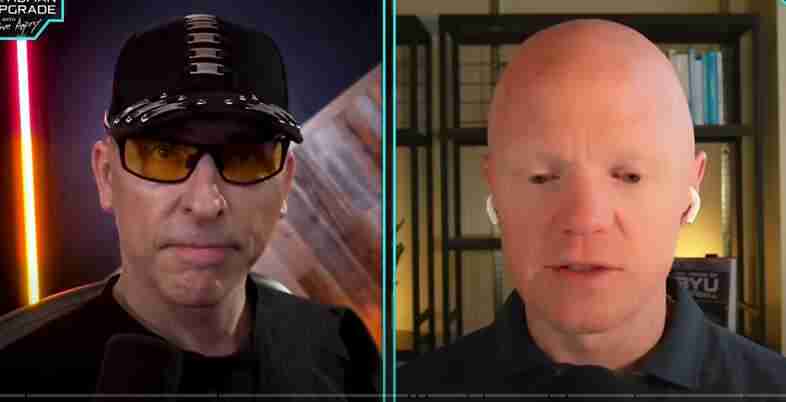

Here is the full transcript of leading expert on insulin resistance and metabolic health Dr. Ben Bikman in conversation with Dave Asprey of The Human Upgrade Podcast on the topic: “Blood Sugar Hack: The FASTEST Way to Burn Fat, Optimize Hormones & Reverse Disease”, February 20, 2025.

Listen to the audio version here:

Introduction to Dr. Ben Bikman

DAVE ASPREY: Today we are going to have an amazing conversation with Dr. Benjamin Bikman or Ben Bikman, who is an absolute boss when it comes to bioenergetics, metabolism, and the way the body actually works. And as you might know, I kind of have a mitochondrial fetish I developed in the late 90s because I had chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia and brain fog and, like, 300 pounds of weight. And I learned from people in their 70s and 80s who are running a longevity nonprofit group. And soon they asked me to run it. And I’m the only guy under 50. So mitochondria have been at the very center of biohacking. It’s like you change the environment around you so you have control of your biology because your mitochondria listen to the environment. So now we have Dr. Bikman here to talk about what’s really going on in there. He’s a fantastic teacher, that very, very learned human being. And I’m excited to share his wisdom with you today. Ben, welcome to the show.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Hey, Dave, thanks so much. It’s nice to be with you again. This is great.

DAVE ASPREY: This is our second or third interview.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: I think it’s our third.

DAVE ASPREY: I think it’s our third interview. I think your YouTube channel, the stuff I’ve seen from you lately on Instagram is so good. You’re one of the few people in academia who’s just willing to say, well, here’s what the evidence says, even though it’s not popular. And I just so appreciate that. Do you take a lot of hits? Like, do you have colleagues like, no cholesterol is bad, and then they’re like, try to not have lunch with you and eat vegan crap and all that?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, yeah. Well, that’s a funny little kind of side comment, but yeah, I mean, one of the most sobering moments of my career came as a pre-tenured professor when I had a bunch of other professors try to get me fired from the dietetics department. Actually, in particular, I was deemed a heretic of sufficient vileness that they tried to get me removed. So, yeah, there have been some naysayers, no doubt. Yeah.

Challenging the Dietetics Establishment

DAVE ASPREY: Well, thank you for fighting the good fight. And if I can just say there are a very few number of functional dietitians. All of the other dietetics or dietitians, they are the McNuggets in hospitals people, they are the school lunch people, and they are so brainwashed or maybe just downright evil, I’m not sure. But they’re the ones saying put, you know, corn syrup and canola oil in baby formula and it’s just not how you do it. By the way, I’m not saying that that is in all baby formula, but certainly around the world it is. And just my biggest critics online are like, the dietetics, the dietitians people. And I’m just like, guys, you’ve done a shitty job. Look at the health of the country and look at people who eat hospital food. Stop talking. And I just move on. Do you do the same thing or are you more polite?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Well, no, I think I definitely have to be a little diplomatic, depending on who I’m talking with. But I agree generally that while there are certainly dietitians and these licensed individuals who challenged the prevailing thought, it is probably the most dogmatic field I’ve ever encountered. And if you deem yourself worthy to step into that territory, you need to be ready for the fiery darts because they come after you.

DAVE ASPREY: Well, they’re very well funded by Big Pharma and Big Ag. So there’s that. You’ve been, I’d say, an outspoken voice on insulin resistance and how it relates to disease, and you’re doing it both in a public sphere with your YouTube and you’re doing it in your book, you know how to not get sick. So talk about insulin resistance. What is it and where does it come from?

Understanding Insulin Resistance

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, insulin resistance is best defined as a pathology with two parts. So it’s a two-sided coin. One side of the coin is the obvious side, and many people don’t appreciate that there’s another. But that obvious side of the coin is the fact that the hormone insulin isn’t working particularly well at certain places of the body. That is the insulin resistance part, that some cells of the body, not all some cells, have become resistant to insulin’s effects.

Now, all of this is compounded by the other side of the coin, which most people do not appreciate. But if you are invoking the term insulin resistance, you’re invoking two parts, the one I just described, but then the other, which most people overlook, which is hyperinsulinemia or high blood insulin. There is no separating the two, that it does not matter if insulin resistance exists in the organism, insulin levels are higher. The two ideas, they are inseparable.

So that is insulin resistance. And of course, the relevance of it is just the fact that it contributes to… Well, not only because it’s so common worldwide, it’s the most common health disorder, but it’s so connected and even in a causal way to virtually every chronic disease. All of these, what I like to call plagues of prosperity, while they do have individual noxious stimuli that can cause them, they have a common one as well. And so the drum that I try to beat so loudly is that there is a common origin to so many of these problems, and it’s insulin resistance.

DAVE ASPREY: The number one cause of insulin resistance is…

The Two Paths to Insulin Resistance

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, number one cause. So more and more, Dave, as I’ve thought about insulin resistance, which I do a lot, I’ve come to the conclusion that there are two paths to insulin resistance. There’s the fast insulin resistance and then there’s slow insulin resistance. And that’s a bigger conversation that I don’t know that we want to get into yet.

But briefly, slow insulin resistance is the result of fat cells that have undergone significant hypertrophy. So that’s the connection of how fat tissue explains insulin resistance. Now don’t assume that everyone listening, that that just means only as we get really fat and obese, depending on the ethnicity, it can be only a little bit of fat gain, and it’s already resulting in larger fat cells that are causing insulin resistance. So that’s an insulin resistance that settles in a little more slowly and it reverses a little more slowly.

Fast insulin resistance, which is the one to I think most explicitly answer your question, is the result of stimuli that can literally trigger insulin resistance within hours, but then they can be resolved within hours to days or maybe a week or so. And in that case, the one that I believe is the most relevant of all of these, what is the most relevant cause of insulin resistance? It is in that fast lane. The most relevant is too much insulin.

And so just to really bring this full circle, because it does kind of create a bit of a circle, I posit that as a person is eating chronic constant carbohydrate consumption, which is the global diet, 70% of all calories consumed globally come from starches and sugars. And so the average individual, because they’ve been told, is eating five or six times a day. It’s all carbohydrate heavy. The average individual spending every single waking moment in a state of elevated insulin, never giving the body enough time for the insulin to come down. As insulin wants to start to come down, they’ve bumped it back up again. And so it’s that chronic insulin that starts to make the body somewhat deaf to the insulin. And that’s then it starts to feed the cycle where too much insulin is causing insulin resistance, which is in turn creating more a need for more insulin, which is creating more insulin resistance.

Debunking Insulin Myths

DAVE ASPREY: I’ve read studies saying that low insulin is four times more deadly than high insulin. Is that true?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: That’s remarkable. I could not believe that to be true and would only believe it in the context of Type 1 diabetes. That might be why, if the population is a Type 1 diabetic population, then I would believe that because it would suggest the person is underdosing to the point of lethality. But in a non-Type 1 diabetic, I would absolutely not believe those outcomes.

But that’s an important point, Dave, because a lot of the confusion that people have with regards to even the insulinogenic effect of macronutrients, like they will say fat causes an insulin release. And yet every single study that has ever shown that was based on a Type 1 diabetic population, where because of their chronic hyperglucagon levels, there is this sort of unexpected quirk of eating fat in a person with Type 1 diabetes. But in a non-diabetic population, there’s zero studies to show that fat has an effect on insulin. None. And so even in my own lab, data we just have generated, we’re about to publish, I can state it authoritatively, dietary fat has no effect on insulin, and there’s never been a study that has ever shown it.

DAVE ASPREY: Thank you for saying that. When I write about fasting and intermittent fasting, I’ve consistently said, if you have some butter and MCT oil and coffee or something like that, it has no effect on insulin or MTOR. And a third party actually went out and tested 300 different breakfast options to see their effect on blood sugar and on insulin. And coffee with butter and MCT was at the very top of the list. Is having no effect whatsoever. That’s why you can do it during a fast.

Two Types of Fasting

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Oh, Dave. Yes. You and I are completely aligned, in fact, to the point that I have… I’ve actually wanted to try, and with your audience, you’re going to make it happen. I actually think there should be some nuance within the conversation of fasting that I have more and more. I consider there to be two types of fasts. One, which is a kind of true classic fast where you’re not eating or drinking any calories that I call a caloric fast. And then what you and I are just describing is what I call a metabolic fast.

DAVE ASPREY: There you go.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Which is what… What determines whether the body’s in, like, at the level of the cell, all of the biochemistry, like, the most famous effect being autophagy. Who determines whether autophagy is turned on or off? Well, it’s actually insulin for the most part. And this is why famous fasting starvation physiologists like Dr. George Cahill, who was a legend to me, he described insulin as the hormone of the fed state.

And in his estimation, which we ought to take seriously, he said, that’s insulin. That really determines whether the body’s in a fed state, high insulin, or a fasted state, low insulin. Well, what if you’re eating in such a quirky way that you are putting calories in, but you’re keeping insulin low? So ketogenesis is uninterrupted, MTOR is not turned on, and there’s no ceasing or inhibition of autophagy as far as the cells are concerned, you’re still fasting.

That’s a pretty metabolically relevant scenario where I believe more and more, as much as there are people who say we need to be doing protein fast, where you’re just eating protein during the fast, I actually think there’s more value in doing fat fasts to be honest. Now, there’s no studies that have compared those two, so I don’t mind if people disagree with. But for all the reasons you and I have just outlined, I actually think a fat fast is superior in its outcomes than any other form of fasting.

DAVE ASPREY: Having tested them all on myself and had hundreds of thousands of followers over the last 10 years, I find the same results and people get really mad. Like, well, in the mice studies, it was just water. It’s because they didn’t test the fat thing. And then I funded some research at the University of Washington around exclusion zone water and cells and how certain types of lipids like C8MCT make mitochondria work better by changing what very esoteric stuff. That’s Dr. Gerard Pollock’s work, and maybe that’s why.

But what I do know is the two types of fasting you’re talking about, like a caloric fast or a metabolic fast. I characterize them as there’s a spiritual fast where you’re okay to be maybe at a lower level performance, and you’re going to push yourself and be introspective. And then there’s a working fast where it’s the middle of the week, I have a job and kids and stuff to do. So a little bit of fat makes the fast completely painless, and you get the metabolic benefits. Because I couldn’t do what I do if I was never… If I was always just fasting on water, I think it would be miserable.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah. Yeah. In fact, because you just invoke spirituality, I will just add a hearty amen. I completely agree with everything you just said.

Insulin and Brain Function

DAVE ASPREY: I always look for alignment and areas where we maybe see things differently. Because, look, I have a perspective. I could be wrong and, you know, a lot. So let’s find the areas where… Okay, that makes sense. And then the areas where maybe I’m fully of crap. What concerns me is if you take a little bit of insulin and you put it in a nasal spray and you spray it up your nose, it’s a way of treating Alzheimer’s. It’s also a really potent cognitive enhancer. So why is it when I raise insulin, my brain works better?

Intranasal Insulin and Brain Health

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah. So I have to speculate a little bit, Dave, just because I want to. And I want everyone listening to know if whenever I mention I’m speculating, it’s because I don’t know of a specific study that I can rely on to answer.

So what I suspect is happening is that with the intranasal administration, you’re able to get that insulin absorbed directly through that upper kind of wall of that nasal cavity. So this is insulin is not getting systemic. In other words, it’s not getting into general circulation. You are just kind of shooting it right up to the brain, especially the hypothalamus, which is right in that lower part or just above that nasal cavity.

And it could be—now I’m theorizing—it could be that as the insulin perfuses directly up through that layer, the epithelium of the nasal cavity and up, it just directly opens the doors and allows a rush of glucose to come in. It would be my speculation now, it wouldn’t be contributing to the elevated insulin induced insulin resistance again, because if I had you on a table and I was measuring your blood insulin levels systemically, like from your arm vein, we wouldn’t get any. There’s no change in insulin at the level of the entire body. There’s no systemic alteration. This was such a modest and such a direct administration.

I suspect it’s just moving right up into the hypothalamus, opening the doors. Because some of the brain’s glucose uptake is dependent on GLUT4, which is an insulin dependent glucose transporter. Whereas other parts of the brain, including in the hypothalamus, it has other doors, other glucose transporters that are just always open. The moment glucose goes up in the blood, it will flow into that cell, whatever the cell may be, the kidney or the liver. But then parts of the body, including the hypothalamus, will have some of these insulin dependent doorways where insulin has to come and knock. Now the door opens and glucose comes in. So it could just be that you are just bypassing any systemic circulation and going right to the brain, saying, hey, brain, I want you to open those doors and really pull in a bunch of glucose.

DAVE ASPREY: That makes good sense to me. And I’ve always been a fan of having exogenous ketones present and doing a little bit of nasal insulin. So I’m like, all right, neurons, you’ve got your ketones, Glial cells, you’ve got your glucose. Let’s go. And that is a pretty good, darn good state of high performance. I just don’t know how often it would be safe to do it, which is why I don’t do it very often.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, I don’t either. Because too much insulin will cause insulin resistance. I do think that’d be one reason, I’d say, to use it judiciously.

DAVE ASPREY: Once a week, kind of.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, yeah. Oh, yeah, that’d be, I think, perfectly fine. But then second, there would be, there’s another part of me that just thinks, well, is that epithelium, that layer of the nasal cavity? It’s not natural for it to see insulin. Would there be some long term effect? Am I stimulating too much growth? Am I going to make the epithelium start to get a little thicker? This is of course entirely speculative.

DAVE ASPREY: Oh yeah.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: But if it’s like on the order of once a week, like you’re saying, that would have, that’s such a modest bolus, such a modest frequency, that wouldn’t have any of these effects. I’m confident.

Identifying Insulin Resistance

DAVE ASPREY: This is so fascinating and I know we’re getting a little bit nerdy on things and at the same time, there are a lot of people who are 50s, 60s, 70s, they’re getting early onset brain stuff. And if you do some research about insulin and Alzheimer’s, you’d want to be on a low carb diet, but you might want a little squirt of insulin every now and then in your brain because it seems to help. And all the metabolic stuff that you talk about and I talk about, if someone’s listening to the show today and they’re saying, well, how do I know if I have insulin resistance? How can you tell with lab tests? And how can you tell with symptoms?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, let’s start with symptoms just because they’re going to be something people can rely on a little more. Well, immediately with regards to symptoms. If you have just been told you have high blood pressure. Insulin resistance is the most common cause of what’s just called idiopathic or just run of the mill hypertension. So if you have hypertension, that’s definitely a knock in favor, a check in favor of you having insulin resistance.

High blood pressure, most common manifestation, if you have a family member with type 2 diabetes, you’re on that spectrum as well. Very likely you’re much more likely to have insulin resistance.

And maybe the final one of the symptoms, before mentioning some clinical tests, is the skin itself, where there are two distinct skin manifestations that are a direct result of insulin resistance. One is called acanthosis nigricans. Then the other one is skin tags. Skin tags is a little more obvious where it’s just like a teeny little like mushroom stalk. Like it’s not a big rounded mole, it’s a teeny little bump. People are probably thinking of it correctly right now, you can imagine there’s these just almost like a little mushroom of skin. And you tend to get them around the neck. You can also get them around the armpit, usually anywhere where there’s going to be a skin fold or a wrinkling or crinkling of skin. You can see these skin tags.

And then the more complicated term I just mentioned, acanthosis nigricans, that’s also at those same locations, like around the collar of the neck, where we all have a little bit of a skin fold. And then around armpits and groin, et cetera, the skin can get a little darker. And now, depending on pigment of skin, that may be easier or harder to see the natural pigment of the person. But the skin will also start to have a texture and appearance of like, crinkled tissue paper. So if we took a tissue paper, crumpled it up, and then opened it back up, that’s kind of how the skin might look.

So this darker, crinkled skin and skin tags, that is proof positive of insulin resistance. And then just if you’re wondering, that’s also imminently reversible as the insulin resistance goes away, the skin resolves in that regard. So skin is kind of a window to the metabolic soul in that regard.

DAVE ASPREY: I remember when I was about 13, I started growing those skin tags. I had hundreds of them. They’re around my neck, armpits, and they used to sometimes get a little irritated or they’d bleed. And—

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah.

DAVE ASPREY: —one day I was, I’m done with this, and I took, like, little fingernail scissors and I just cut all of them off because they have a tiny little stalk. They don’t really bleed when you do that.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah.

DAVE ASPREY: And it just frustrated me. I had no idea what it was. I thought maybe they’re warts. And I’m familiar with that as a sign of insulin resistance. And there’s a lot of listeners right now going, oh, my God, I started growing those. They went away when I went into ketosis for the first time. And when I did the whole bulletproof diet thing, I don’t have them. And I didn’t have to cut them off. They just disappeared.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: That’s right. Yeah. So the nice thing about the skin in this regard is that it is so dynamic. We are growing and sloughing skin literally every moment. And so as the insulin levels start to come down, that hyper excitability of that layer of skin cells, because insulin basically starts to stimulate this kind of sporadic growth. Insulin likes to grow things that is not inherently bad, we need it. Without insulin, you die.

So lest anyone thinking Dave and I are painting insulin as the villain. No, but the poison’s in the dose, if you will, where we’re talking about when it’s gone beyond normal levels, insulin’s resulting in this kind of frenzied growth of these skin cells. But again, the nice thing with the skin, it gets sloughed off so readily, literally all the time, that once the stimulus to keep growing goes away, I mean, give it like just week, just a couple weeks, and they’re likely going to start literally, just you’ll notice them smaller, smaller and they’re gone as they just wear off.

And now the clinical tests. Just for the sake of time and not getting into too much depth, I’ll just mention two. One is just getting insulin itself measured. This is, I believe, one of the greatest mistaken approaches of conventional clinical care. Despite all of its problems, we have a glucose centric paradigm of metabolic health. And the conventional clinician is content just once a year measuring someone’s glucose levels. And glucose is a late signal that while glucose levels are staying normal over years and the person’s developing hypertension and erectile dysfunction and migraines, it’s insulin that’s been the canary in the coal mine. Metabolically, it’s getting higher and higher and higher.

So look at your insulin. I generally outline three ranges. If it’s 6 micro units per mil and lower, that is, that’s really good, solid sign, absolute green light, less than 6. And then if it’s 7 to mid teens, I just say 7 to 17, then it’s sort of, you know, hey, possible problem. Now I, as a scientist, I don’t like being a little soft in my wording. I like to be very clear and definitive. But insulin is a hormone and every hormone has its own ebb and flow.

So the reason I kind of give a bit of an if with that range is if someone had their insulin measured and it’s 11 or 12, they would say, oh shucks, I’m busted. Yet that might have been just a peak moment where your insulin might have been kind of peaking up as it has a natural circadian rhythm to it. And so if it’s in that middle range, you might be alright. All the more reason to rely on the second one I’ll just mention in a second. But you might not be. And then if it’s high teens and beyond, absolute red light. Even the normal volatility of insulin shouldn’t be getting that high in an insulin sensitive person. So high teens into 20s. Warning, you’re insulin resistant. Red alert.

Now, the other metric is valuable because it’s not as volatile and it is surprisingly accurate or a good predictor, a poor man’s method. And that is the triglyceride to HDL ratio. So just take your fasting triglycerides divided by your HDL and that’s going to be really good. If that number, there is some differences across the ethnicities. So the general rule is 1.5. If that ratio’s above 1.5, that’s a red light. That’s a warning.

Now, in some other subsets of populations around the world, like East Asians, Japanese, Korean, that number ought to be actually closer to one, so it’s a little more strict. So a triglyceride to HDL ratio of one is your cutoff. Lower the better. And then in blacks and I think Hispanics, it can be a little higher where the normal cutoff’s going to be about 2.0. Okay, so it’s going to be around that 1 to 2 range. If it’s higher than that. Warning. Metabolic dysregulation.

DAVE ASPREY: Does it change for men and women?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, that’s a great question. No, no, because those numbers are pretty static across the sexes. It’s funny you bring that up though, because the one lipid that isn’t is free fatty acids. If anyone ever measures free fatty acids, which is not the same, you know, triglycerides are what the liver is making or what you’re eating. Free fatty acids are 100% a product of what the fat cells are breaking down. And women due to estrogens. Most gals don’t appreciate this, but a woman at any moment is burning 40% more fat than her male counterpart.

DAVE ASPREY: What?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: And you see this? You see this in her free fatty acid levels. Now, Dave, before we fellas claim defeat here and say we’ve been robbed, she’s also putting in more fat at any moment, too.

DAVE ASPREY: And so because she’s eating more fat or because her—

DR. BEN BIKMAN: No, no, not at all. Just because of sex hormones. So estrogens are both stimulating the breakdown and the building up. So females just have a much, much higher rate of turnover in their fat cells. You know, so it ends up. Because the overall dynamic is she will have more fat on her body than her male counterpart, which she’s supposed to. It’s by design, because she carries the metabolic burden of reproduction. She needs to have this kind of metabolic insurance before she ever commits to the metabolic marathon of reproduction. But she’s also turning it over a lot faster. So her free fatty acids will be normally about 40% higher than what you see in a guy. But the other lipid measurements are generally going to be in that. At least those ones are going to be generally in the same range.

DAVE ASPREY: What I found 99% of the time when people go on something like the bulletproof diet, which is clean, cyclical keto, the right kinds of animal fats, controlling type of protein, toxins, all the stuff that I’ve been teaching for a long time, HDL goes through the roof and triglycerides drop, which is exactly what you want for this ratio.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: It sure is.

# Blood Sugar Hack: The FASTEST Way to Burn Fat, Optimize Hormones & Reverse Disease

The Relationship Between Carbohydrates and Triglycerides

DAVE ASPREY: And when I went to my first longevity doctor when I was maybe 29, it was a long time ago and I came in with that pattern, he just looked at me, said, well your lipids are technically disordered but really good because my HDL is like how did you get it so high and why is your triglyceride low? And it was because of the idea of intermittent fasting and things like that.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, you’re doing it right, that’s the right way to do it. And it is a consistent finding that you start to control carbohydrates. Triglycerides are going to come down because it’s namely the elevated insulin that is spiking the production of triglyceride rich lipoproteins from the liver. So as carbs go up, triglycerides will go up. As carbs come down, triglycerides will come down.

Dave’s Body Transformation and Fat Loss Challenge

DAVE ASPREY: I have a confession to make about an experiment I’ve been running for the past probably year. I am down to about 5% body fat. I am crazy, crazy lean. And this is on using, you know, $26,000 clinical grade bioimpedance things and lots of different measures. And I used to weigh 300 pounds.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: So isn’t that amazing? What a testament to just how adaptable and dynamic the human body is.

DAVE ASPREY: It blows me away. And like my new book cover, I’m on there with my shirt off and I’m like the fat computer hacker who had never. I didn’t want pictures of me when I was fat. So I’m still kind of stunned by it. But here’s the problem. 5% might be below ideal for longevity. I think closer to eight is where I want to be. And I’m really having a hard time putting on fat. And I have half of a large bath towel’s worth of extra skin for when I was obese.

So I went in a couple of weeks ago, just posted about this online. And they removed a passport sized piece of skin from each side of my face and neck. This isn’t from aging skin. This is obese skin. Probably aging, I don’t know. And I’ve been healing really fast. But they’re saying, Dave, we need some fat to put in with stem cells in your face to get the volume back. So I have been pounding the carbs, Ben, like 400 grams of rice and honey and fruit and watermelon, and I have not put on any fat. They found 20cc’s when they like completely emptied my butt of all the fat they could find.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Oh, my gosh.

DAVE ASPREY: So how is it that I’m not getting fat on 400 grams of carbs? I’m doing 200 grams of animal protein. A. Okay, I’m only eating good fats. What’s going on?

The Science of Fat Storage and Insulin

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, yeah. Well, so I can’t state definitively, but generally there are going to be two essential variables that determine the growing and the shrinking of the fat cell. Now, your audience is savvy enough to know that there is more than just one variable, which is the traditional view being that it’s just purely calories in, calories out. That is so easily disproven. But, and I’m not saying, like, just so everyone knows, I’m not saying calories don’t matter, but that is the only message anyone ever hears that people think that’s what I’m saying.

And if I kind of claim any authority, and I’m loathe to do this, I have such a general disregard for higher education and terminal degrees, like a PhD, which is ironic, I know, but I’m surrounded by PhDs. And so I’ve seen how dumb many of these people are, and I hope I’m not one of them. And I don’t necessarily just mean my colleagues here. I love them all dearly. But if I’m going to make any sort of stake a claim here, I have a unique PhD. And you noted this in the introduction. It’s very uncommon. There are only, I think, two institutions on the planet that grant a PhD in bioenergetics.

Bioenergetics is a particular niche of research that combines the metabolism, biochemistry and physiology, but with a heavy focus on thermodynamics and the relevance of thermodynamics in living systems. Because, lest anyone has forgotten, thermodynamics was originally posited as a view to make the better steam engine that it is in the realm of physics. And it is an odd or it’s an awkward fit to try to fit principles of physics in principles of biology.

I actually think that I’ll make this kind of a bold claim. I consider the introduction of calories into biology as part of what got us where we got it wrong. It so thoroughly distracted us from, I think, what matters most, that it actually brought us to where we are. I think the whole war on fat, in part was born because of this improper introduction or invocation of thermodynamics.

Now, having said all that, calories matter and those carbons need to be accounted for in some way. But a cell, like, especially a fat cell, it needs to know when it’s time to eat and when it’s time to break down. And the fat cell wants to be, and everyone, pardon me if it sounds like I’m being silly. I am, after all, a professor who teaches 18 year olds, so I have to sometimes be a little juvenile in my description of things.

But the fat cell needs to know that it’s playing nicely in the entire neighborhood of the body, that it needs to know, okay, what are the demands of the brain right now? What are the demands of the muscle? There’s no direct nerve that’s connecting them. It’s hormones that generally will tell the overall orchestra when it’s the woodwinds section to play, when it’s the brass section or when is it time for the muscle to be needing energy. But you couldn’t. You don’t want muscle to be exercising and pulling in energy to break it down at the same time. Fat is taking in energy to store.

The body, in its overall balance of metabolism, wants to balance out the two parts of what is metabolism, anabolic versus catabolic. Insulin is the hormone that sends that signal. So this is my really long winded way of just saying I have right now, down the hallway in my lab, fat cells growing in petri dishes. Like literally right now, I’m not even being hyperbolic here. Those fat cells, when we first plate them and they’re sticking to the cell, to the bottom of the dish, they are in a bath of tons of calories, tons of fat and tons of glucose. Everything a fat cell wants in order to grow, but it stays small until we do one single thing, which is add insulin into the culture.

The moment insulin comes into that little culture media we call it or that bath. Now, the fat cells would say if they were part of the greater whole, ah, it’s time for me to eat. This is my signal that it’s time to store energy rather than break it down. And now we look if we look at those fat cells just four to six hours later, they’re actually thicker, chubbier. If we look at them six hours later, still, they’re bigger again.

So all of this is just to say that there must be a stimulus that tells the fat cell to grow, which is elevated insulin, and then there must be sufficient calories to fuel that growth. You cannot have one without the other. And just to really put a fine point on that, if a person had high insulin and low calories, they will die because they would become hypoglycemic and there would be no ketones being produced because the high insulin would be inhibiting ketogenesis. And then the brain would have been deprived of its two fuels and the body would shut off. The brain was shut off.

Now, in contrast, if insulin’s low and calories are really high, what happens then? Now the person is burning up almost. They burn to death, where their metabolic rate and their ketogenesis is unstoppable because there’s nothing to tell the body to stop burning energy. And so they die from ketoacidosis and hyperglycemia. But this is a scenario which is so real that. And it works, where you can eat as much as you want, that people with type 1 diabetes, some of them have learned and are so tempted that they can deliberately underdose their insulin level and be into a state of ketoacidosis and massive hyperglycemia and feel miserable and wretched. And yet they will be as thin as they want.

Just everyone imagine the temptation. You know, they don’t have to vomit up their food. They don’t have to starve themselves through traditional anorexia. They can eat everything they want. They can enjoy the sensation of eating it and swallowing it and digesting it, which has its all of its own gratification. And all they have to do is not poke themselves with a needle and inject their insulin. That’s a condition called diabulemia. And all of this is just to say there are two parts. The fat cell must be told to store insulin or to store fat via high insulin. But it needs sufficient calories to fuel that growth. It’s one thing to tell the fat cell, let’s grow. Then the fat cell has to grow.

Low Insulin, High Calories, and Metabolic Effects

DAVE ASPREY: So low insulin and high food intake equals thin and lots of energy. But I guess they feel like crap.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Oh, yeah. I mean, yeah, you can read case reports where the people will say, like, I felt. I feel like I’m dying, but I want to stay thin.

DAVE ASPREY: Wow. Yeah, That’s Unhealthy.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: I mean, just imagine.

DAVE ASPREY: Yeah, Yeah. I did notice when I was testing out the edges of the recommendations before I published the bulletproof diet. And I published that in 2014. I published online in maybe 2013. I went for about a year, and I was eating 4,500 to 5,000 calories a day on purpose, more than I wanted. Like, forcing myself to do it, eating no carbs, and I was sleeping less than five and usually less than four hours a night on purpose. Like, I’m going to set myself up to get fat. I’m going to prove that I don’t get fat the way I should.

But I kept losing weight. I grew abs for the first time on crazy amounts of this. I knew my insulin was low because I had it measured. It was actually pretty darn low. Don’t remember the number off the top of my head. And that probably explains. Well, I didn’t feel like crap until kind of maybe halfway through. I started getting cortisol effects where I would wake up dozens of times a night. My sleep quality went down. You start getting reductions in testosterone, thinning of hair, and all of that. And I stopped it.

But I meant to do it for a month to just make fun of the calorie people, and I ended up doing it for a lot longer because I’m actually in a really strong state of high performance. Why did my brain work so well when I did that, at least for the first six months?

The Brain’s Preference for Ketones

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Well, Dave, so you brought up a lot of stuff, and I don’t want to not answer the question that you started with, which is why you’re not gaining fat. So let me come back to that first part, and then to answer this part right now. Yeah. I mean, ketones are the preferred brain fuel. One of the notions I attempt, that I need to disabuse my students of is that they’ve been told the brain prefers glucose and you need to eat this much glucose. There’s multiple things wrong with this. Not true. Not true.

But just to really establish the relevance of that, I showed them research from Dr. Cahill where you can take someone with a glucose level of. I’ll use the same kind of units here. Let’s say 5 millimolar, which would be kind of 80s milligrams per deciliter. And if their ketones are at 1 to 2 millimolar, so less than half of what the glucose is, the brain’s already getting most of its energy from the ketone.

So don’t tell me the brain prefers glucose. If anything, the brain has a preference for ketones, which Dr. Richard Veech and many, many others, my own lab, has reported papers on this. It enhances mitochondrial performance. For every oxygen unit of oxygen that the mitochondria are consuming, when they’re fueled with ketones, they’re producing more ATP.

DAVE ASPREY: Yes.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: So what we described that in my publication is that the ketones were resulting in a tighter state of mitochondrial coupling, which is how much energy am I breaking down in order to produce this energetic molecule, ATP? And it was better. Now, in your case of what you’re trying to do now, one of the reasons I point the finger at carbs is because of what it does to insulin. And so in your situation, you are either now so exceptionally glucose tolerant that even though you’re eating hundreds of grams of carbs, if we were to act, you’re clearing it so quickly that it’s never resulting in substantial insulin spikes, or. Well, that’s it. You’re just that insulin sensitive and glucose tolerant.

DAVE ASPREY: HbA1c went up in a way that I don’t like. So I’m on low carbs now.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, but do you. But are you still in ketosis pretty often. Have you been measuring your ketones during this?

DAVE ASPREY: Not with a finger stick, but I just use exogenous ketones several times a week. I know there’s ketones. Ketones present a meaningful portion of the time.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Well, I would be curious if you like, in a morning. So one day, like on.

DAVE ASPREY: On.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: On a. Today you ate 500 you 400 grams of carb, but tomorrow morning, if you measured your ketones, if you are in ketosis, then your insulin’s not really going up that high.

DAVE ASPREY: Interesting.

Physical Activity and Insulin Sensitivity

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Not only. So the other point I meant to make is that you’re either. It’s a combination of you’re super insulin sensitive and you’re just maybe so physically active. I have known really active individuals who eat hundreds of grams of carbs and they’re still in ketosis the next day because they’re just burning so much of the glucose. And the magic of the working muscle is that it can pull in that glucose without the need for an insulin spike. As I mentioned earlier, insulin wants to store energy, which is antithetical to exercise, which wants to break down energy. It wants to break down what’s been stored.

And so exercise quickly lowers insulin due to the sympathetic stimulation. Basically, the body starts moving, and then the brain starts to tell the pancreas, hey, you gotta shut down insulin production. And it does so very quickly. And so all of this can combine that if a person’s already insulin sensitive, which you certainly are, combined with high levels of physical activity, if you aren’t getting elevated insulin for pronounced periods of time, it doesn’t matter if you’re eating those calories, you’re not going to store it as fat.

DAVE ASPREY: Even if my blood sugar goes up, but my insulin isn’t going up, you’re saying?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, well, it could. That’s exactly right. Yeah. So glucose is not a perfect surrogate for insulin as much as we wish it were. Yeah. It is important because while we can measure glucose so readily, it is. We are years away from having a continuous insulin monitor and they’re not the same.

Like, for example, if Dave were to take 100 grams of carbohydrate and then immediately go exercise, we would see that spike. Depending on how intense the exercise is, it may even stay high for a while. But no insulin was required during that exercise. As it starts to come down, it’s not because insulin went up, it’s because the muscles are pulling it in on its own. Because again, when the muscle contracts, it has an insulin independent way of opening its doors.

You’d mentioned MTOR earlier and I know you’re familiar with MTOR’s opposite, which is AMPK. When you start to contract and relax the muscle, it’s flooding the muscle cells with calcium. Calcium, as it goes up, will activate an enzyme called calcium calmodulase kinase or camkinase. So a calcium activated enzyme, Camkinase, will then activate AMPK. AMPK will then activate AS160, which activates GLUT4. And now we’ve opened the glucose doors and we’ve been able to pull in that hungry muscle. Basically says to insulin, hey, I’m too busy to wait for you to tell me what to eat. I’m just going to eat this because it’s here and I’m going to pull it in.

DAVE ASPREY: This is why even going for a walk after you eat carbs or doing some squats, it doesn’t really matter, not even weighted squats. Just do you have 30 air squats and you can watch. I’ve used a glucose monitor for long periods of time and you can see, oh yeah, ate carbs, it’s going to go up and then you do a little bit. And if you actually do a real workout with weights or something and real resistance, you’re not going to get much of a spike at all.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah. So that might be part of your problem. Honestly, Dave, for you to gain weight, you may have to start changing so many habits.

DAVE ASPREY: I don’t exercise that much. I do really good exercise with AI stressing the system from the upgrade lab stuff. I do about 20 minutes a week of real exercise, and it’s carefully scripted to exhaust and then recover very quickly. So I don’t think my volume is high, but my recovery is high and my intensity is high. So I’m like, I’m a weird robotic cyborg biohacker guy testing out weird stuff. And I just, like, you would probably know why. Is it possible to have my average glucose go up and eat ridiculous amounts of carbs, sometimes more than I want, and then to not gain one pound? And it sounds like you figured it out.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Well, I think that if we really need to know what your insulin levels are, it’s entirely possible that your fasting insulin levels are still in an exceptionally good range and that what you think is a big insulin spike, it could be much more modest than you realize. And if that’s the case, then you’re kind of getting into that physiological scenario of what we see with diabulemia, which is that the insulin levels are getting so low that it’s just incompatible with storing fat.

The Myth of Calories In, Calories Out

DAVE ASPREY: Mm, that makes so much sense. Okay, I want to touch on one more thing about calories in, calories out. Because you and I have both been trolled by these, like, angry 25 year olds, you know, cancel out a Snickers bar with a Diet Coke kind of people. And I just laugh like, well, if calories counted, there’s a million calories in a gram of uranium. And they go, but you have to be able to absorb it. I’m like, oh, thank you. So calories don’t count, calorie absorption counts.

And then they start twitching, usually, which helps them burn more calories, which probably is good for their weight loss. And then I say, well, do you know about Xeronol? And like, no. Well, it’s a drug derived from mold toxin that’s 10,000 times more estrogenic than normal estrogen. And if you give it to a cow, which ranchers do, the cow will get fat on 30% less food. So if the drug can exist and there’s tens of millions of dollars being spent because it works, it’s not about the calories.

I’m not saying that they are relevant in some way. But this idea that I’m going to somehow know how many calories I burned without being in a calorie chamber, that’s nonsense, because only half your calories are from moving. The rest of the stuff is respiration, temperature, humidity, stuff that no one’s going to measure. So you don’t know how many you burned and you don’t know how many you ate. Because the dumb little apps, like as a guy who makes, you know, $100 million plus of food things, the number of times that I’ve gotten in trouble because when I buy a frickin cashew, the calories per gram varies based on the time of year. So you can’t even say a gram of cashew always has the same calories.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah.

DAVE ASPREY: And so my labels have to be within a very narrow window. And so it’s complete fantasy that we can measure what we’re taking in or what we’re putting out. Which is why I’m like, this is just a distraction. Which is what you’ve been saying as well.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Well, yeah, and you can see why I feel so strongly, as much as I appreciate thermodynamics. But the problem is we don’t eat heat. A calorie is a unit of heat. We don’t eat heat. Like, if we eat a warm Snickers bar, does that have more calories than a cold Snickers bar? Because if it’s just pure calories, and it is, then drinking a hot coffee, that’s not a good example. But it’s not calories that matter.

In an ideal world, if we really wanted to have a food label that gave an idea of how fattening this food will be, which is what the calories are trying to do. The whole reason we have calories is this idea that, hey, you need to control your body fat, so look at these calories and count them all. It is such a fool’s errand. For all the reasons you mentioned, it is impossible for the average individual to capture every calorie coming in, let alone every calorie going out.

Now, by going in, not only did you mention how even on a label, it might have gotten it wrong, but you don’t know how much you’re absorbing. You don’t know what the thermic effect or the caloric cost of digesting and absorbing that food is. And again, it’s not units of heat that you’re getting.

So in the ideal world, if there, if we deemed it necessary to have some metric on a food label, it would be some combination of how much is this going to spike your glucose and how much is it then going to spike your insulin? How many other carbons are coming with it? Because dietary fat matters if insulin’s high at the same time, and because then you’re storing those carbons very readily. But it’d be some kind of algorithm that would give like a fat index or a fattening index, rather an obesogenic index that would say the combination of carbons or calories, if we have to use that term. And insulin spike means that what you’re about to eat is going to be more obesogenic than, say, something else. That would be more of an ideal scenario because, again, it’s not units of heat. Calories don’t really work in that sense.

But one other comment on this that I thought while you were explaining the scenario earlier, when insulin comes down, as I’ve mentioned now a couple times, it is so antithetical to the body storing energy that someone will say, well, where does that energy go? You have to account for it. And I agree that you have to account for the carbons, they need to go somewhere. But the body, it is so antithetical to storing carbons when insulin’s low that the body has these release valves, these pressure valves, in two forms.

One is that when insulin is low, metabolic rate goes up. We’ve known this for 100 years by studying people with type 1 diabetes, there is a substantial elevation in just resting energy expenditure, just the cost of living. The body’s just running hotter, the engine’s idling faster. When insulin’s low, my lab published a report finding that part of it is because of the effect of ketones. We found that when a person was in ketosis, and we did human fat biopsies, that their metabolic rate from their fat tissue was three times higher than when they weren’t in ketosis. So there is just this increase of metabolic rate and fat tissue itself. So when insulin comes down, metabolic rate goes up. That’s one part of it.

The second part of it is that’s the wasting in the form of heat. What I just described, then it’s wasting in the form of ketones. Everyone remember, ketones have a caloric value that is almost the same as glucose. And when you’re in ketosis, you are breathing out ketones, which is to say you’re breathing out calories and you’re urinating out calories because you have ketones that are getting excreted in your urine. And remember, ketones have a caloric value, or in other words, carbons that could be used.

DAVE ASPREY: That’s amazing.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Wasting them.

DAVE ASPREY: How did I not know that? I never thought of it. So that’s one of the benefits of intermittent fasting or being on a ketosis kind of diet. You’ll breathe out calories and you’ll pee out calories.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah. I mean, how did I miss that? The collective effect of all of this could be as high as 5 to 600 calories. Holy crap. I mean, that’s a lot of stair stepping. That’s a lot of exercise to try to get. I mean, anyone, next time you’re working out, see how long it takes you to get to 5 or 600 calories burned as opposed to just being in it. No, it’s so long. It’s so hard just being in a ketogenic state. You’re doing it without even thinking about it.

This is why you and I are able to say, don’t count calories if you’re hungry. Like to the average person who wants to lose weight, the traditional view is cut your calories. But if you’re not addressing your insulin, that’s just going to promote hunger. Hunger always wins. Before you know it, you’ll be right back where you were.

So let your first step on your weight loss journey be, I’m going to lower my insulin. Calories will take care of themselves. Just control carbs. Eat good protein and good fat. And when you’re hungry, eat. If you’re not hungry, don’t eat. And with this plan in mind, insulin will come down again. Calories will take care of themselves.

DAVE ASPREY: Are people going to lose muscle mass if they go into ketosis and they lower insulin?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: That’s a great question. I’m happy to answer it because I can rely on some good research. Two thoughts come to mind. One was the Scottish man, I think, who fasted for 384 days and then worked from my own lab. So let me start with the Scottish guy. This is a documented case report where he literally fasted for more than a year. And Dave, something I actually thought about earlier when you were describing kind of your own feeling and then the cortisol, it’s for people to understand the difference between a fast and starvation.

DAVE ASPREY: Yes.

Ketones and Muscle Preservation

DR. BEN BIKMAN: The difference between those two is fat tissue. If you have fat tissue to burn, that means you’re making ketones, which means you’re feeding the brain everything it could ever want. As you start to run out of fat, now you run out of ketones. Now the brain has to rely on glucose. And what’s the main source of glucose? It’s going to be amino acids in that state, not in the normal state. In a normal state, it’s most of the source of glucose is coming from lactate, by the way.

But with long term fasting to the point of, I’ve run out of fat tissue. Now the body starts breaking down muscle to get those amino acids to convert those into glucose and cortisol helps it happen. Now, in this guy, he had so much fat because he was morbidly obese. He didn’t lose muscle. He maintained his muscle mass throughout this entire fast.

Now, in my lab, we published a report finding. In fact, it was right after we did the fat cell study, where we looked at how fat cells respond to ketones by increasing the metabolic rate, and there’s a lot of wasting of energy. We did a comparable study, not quite as strong. We didn’t use humans, but we did a comparable study with muscle tissue and ketones. And we found that ketones enhance mitochondrial coupling of the muscle. So the muscle’s getting more efficient with its use of energy, and the muscle cells were more robust as we kind of insulted the muscle cells with some chemical stimuli to kind of knock on them and hurt them a little bit.

When muscle cells were fueled with ketones, they were more rigorous, they were tougher, they were more viable and more resistant to injury, suggesting that at the end of it all, people have long said that ketones defend muscle. Now, what they meant by that was that if ketones are up, then there’s going to be less breakdown of muscle because we don’t need those amino acids for gluconeogenesis, which is true. But my lab added evidence to this, which is to say that ketones really are defending the muscle, because when muscles are fueled with ketones, they’re literally tougher. They’re harder to kill.

DAVE ASPREY: These are really good arguments for cycling in and out of ketosis. I’ve found that when I stayed in ketosis for long periods of time, that I would develop insulin resistance. This seems like a common occurrence. So that’s one of the reasons I recommend cycling. So talk about insulin resistance and people in ketosis for long periods.

Ketosis and Glucose Intolerance

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Oh, I’m so glad I have a chance to bring this up. Yeah. So, Dave, you’ll not be upset for me to say that’s not insulin resistance.

DAVE ASPREY: Oh, cool.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: What people are describing in that case of a ketogenic diet causing insulin resistance. It’s not insulin resistance. Insulin is working exceptionally well. What it is is an acute glucose intolerance.

Now, let me sort of provide some interesting context here. People have heard of the concept of metabolic flexibility, which is this idea that when you eat a mixed macronutrient meal with carbs, you go to glucose burning mode and you can detect this. And then when you enter a fasted state about five to six hours later, because insulins come down, you go to a fat burning state. So the body shifts between sugar burning and fat burning.

Some scientists at the University of Pittsburgh, years ago, 25 years ago now, I think documented this concept of metabolic inflexibility, which is where there are people who have insulin resistance because that’s the cause of this, that when they eat, they’re in glucose sugar burning mode. When they’re fasting, they’re still in glucose and sugar burning mode because their insulin is still elevated, which is insulin resistance. So they’re stuck in sugar burning mode.

Now, in the long term, adherence to a ketogenic diet, I like to say you kind of have an inverse metabolic flexibility scenario where it’s almost like the body is stuck in fat burning. Now it’s not. What has actually happened is if you’ve been in a long ketogenic diet, actually it doesn’t even take long. Even if a person fasts for 24 hours, what I’m about to describe is happens to them as well.

So if someone goes and takes an oral glucose tolerance test, they go, drink a bunch of glucose, you measure a glucose curve and you see it come up and down and say about two hours, it’s back down to about 100 milligrams per deciliter. That’s a good response. Now if this person were to then adopt a, well, even fast for 24 hours, let alone be in a ketogenic diet, if they take that same oral glucose tolerance test now, you would say, wow, my glucose went higher and it took even longer to come down. It didn’t come down until three hours or three and a half hours.

The temptation is to say, I’m insulin resistant now. Because if you were looking at a person with type 2 diabetes, that is what’s happened. But that’s not what’s happened in this person who maybe just fasted a little too long or is on a ketogenic diet. In that case, it’s because of a lack of preformed insulin in their beta cells.

So basically, when we eat carbs, the insulin, the beta cells want to be ready. And they literally have a bunch of prepackaged insulin in the beta cells stored like on the shelves behind me, ready to go. Here I am in my beta cell office, insulin, glucose comes up. I get a knock on the door. I know, okay, I got to address the glucose. I’m going to start shipping out all of this insulin I have made right now, which is called the first phase insulin release. But I am constantly monitoring the glucose. I know this isn’t going to be enough. And so at the same time I’ve been shipping out my preformed insulin, I’ve started making more insulin. That’s the second phase insulin release.

When a person has fasted too long. Well, 24 hours or so, that’s not too long. But prior to an oral glucose tolerance test it is. Or they’re on a ketogenic diet. The beta cells are so efficient, and I’m sympathetic to this because I hate clutter, that the beta cells basically start to say, hey, I got all this stuff on my shelves here and I’m not using it, I’m just gonna get rid of it. And so it literally breaks the insulin down to its base amino acids and then just recycles them and does anything it wants with them.

But it starts to think, I don’t need all this insulin. And then all of a sudden, hold on, red alert, we need glucose has just flooded the system. Oh, crud. The beta cell says, well, I don’t have all the insulin made, so there goes that first phase insulin response that I’d normally have. But I still have the ability to make a bunch of insulin. It’s just gonna take me a little longer.

So body pardon me, beta cell, for being too efficient. It’s gonna take us a little longer to clear that glucose. But says the beta cell, to finish off this weird story, if you do this again within a 20 hour period or so, I’m gonna keep this insulin here just case we do it again.

So my long winded way of saying it’s that there has become an acute glucose intolerance because of a very temporary reduction in insulin on hand preformed. And so if a person is on a ketogenic diet or they’re going in for an oral glucose tolerance test and they think that they’re going to crush it by fasting for 24 hours, you’ve actually set the stage to get a false positive or you’re gonna fail that glucose tolerance test or get a worse score because you haven’t eaten carbs recently.

So eat some carbs eight hours or so before you go take the test. And it doesn’t have to be sugar, just eat some starches. And then the beta cells will say, ah, okay, maybe we’re gonna start getting into carb consumption again. I’m gonna hold on to some insulin so that when we do this test in 8 or 12 hours, I’m gonna be ready for it. And then you’ll pass it with flying colors.

Because a ketogenic diet will improve insulin sensitivity exceptionally well. Remember, Dave, that everyone, remember the way I described insulin resistance earlier applies every time we invoke the term insulin resistance, which is insulin will be high. If insulin is low, it is impossible for the body to have insulin resistance. So this scenario isn’t reflective of insulin resistance, but just rather a temporary state of glucose intolerance, because the body’s kind of been saying, well, I’m not sugar burning, I’m fat burning. Oh, hold on.

DAVE ASPREY: Wait.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: You want me to go back to sugar burning? All right, well, I wasn’t quite prepared, so pardon me while I just sort of make some adjustments and I’ll be better prepared next time.

DAVE ASPREY: You just taught people how to preload insulin. If you’re in ketosis and you’re going to do a life insurance test, that.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Would be important 100%. And I want people to know that, like, if I imagine, you know, a pregnant gal who’s been in a ketogenic diet to help with her PCOS and get pregnant, now she has to go in for her oral glucose tolerance test. You want to eat some carbs in at least some period of time before you go in 8 to 12 hours just to have that insulin on hand, and you’ll be just fine.

Timing of Insulin and Blood Sugar Measurements

DAVE ASPREY: Oh, that’s such a gift. Thank you for sharing. There’s some other things that affect insulin and insulin resistance, like circadian rhythm. We know melatonin going up will make you insulin resistant. We know that at night you’re insulin resistant. So does it matter when we measure our insulin and when we measure our blood sugar and when we eat?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah. Yeah, it does. In fact, tragically, measuring insulin in the morning is probably one of the worst times. And that’s why I kind of described that there’s that bit of that gray area, that kind of orange light range or yellow light range, where insulin might be a problem or it might not be.

And I actually kind of bake that into the formula because of the morning volatility, that when we’re waking up in the morning, we will have higher cortisol levels naturally, which starts to just mobilize the glucose to get ready for the brain to come back online, if you will. You know, as the body starts to wake back up and get alert. But also insulin can start to climb in response to that glucose climb. And so morning is one of the worst times, but it’s the most convenient because we’re fasting overnight. We need a fasting state. If in an ideal world, we wouldn’t measure fasted blood levels until, you know, late morning or early afternoon to let that pass.

DAVE ASPREY: Can you adjust for that? Like, let’s say you, you do your insulin test in the morning and it’s. Should you just subtract a point off of the morning score to get a more accurate.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: I don’t know. I don’t know. That’s a really, really good question.

DAVE ASPREY: That’s therapy lab. This is, this is.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, you’d want to, I mean, what you’d want to do is take that same person, measure their morning, and then measure their afternoon consistently across a group of people and then find out that, okay, here was morning, giving us a little bit of that false positive range or a false concern. Here was afternoon.

So if we make this kind of algorithmic adjustment, it allows us to get the morning, which is the easiest time to do it. Everyone wants to do their fasted tests in the morning so they can end their fast. I get it. But yeah, it would be nice to be able to kind of have an adjustment on hand to say, okay, well actually it came in at 15 microunits per mil, but based on what we see across the population, if we were to measure this four hours later, it would have come back down to seven. Okay, so you’re actually doing great. Yeah, that’s never been done.

DAVE ASPREY: Wow. Well, this seems like something your lab would be uniquely suited to do.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, we could hope for that.

DAVE ASPREY: We’ve talked about doing something squats after a meal or going for a walk to lower blood sugar, which ought to also lower blood insulin. We hope. Are there other non dietary things we can do? Biohacks like red light therapy, pulsed electromagnetics, cold plunges. What do those do?

Cold Therapy and Metabolic Benefits

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, so the only one I can speak to with some authority is cold plunge. Although I think everything you’ve just mentioned does help, including just sauna. It’s the interesting quirk of just temperature extremes with cold immersion.

The results are really remarkable across the board. And I am an unapologetic advocate of cold immersion. There are two mechanisms that cold therapy will engage. One is shivering-induced thermogenesis, and the other is mitochondrial uncoupling. Brown fat is the most famous example of that.

With the shivering, the whole body contraction of the muscles – that’s really exercise. You are contracting and relaxing muscles in order to generate heat. Well, that heat has to come from burning something and a lot of that something’s going to be glucose.

At the same time you’re shivering, you’re also sending a signal to mitochondria, particularly in fat tissue, that “hey, mitochondria in fat tissue, I need you to become less efficient,” which is to say I need you to burn energy to create heat. Because heat is a waste product, but when the body gets cold, it actually gets a little wasteful. It starts to want to burn energy just to create more heat.

So you have this uncoupling where the mitochondria – it’s basically like you’re revving the engine in your car, but you’re keeping your foot on the clutch at the same time. You’re getting high RPMs, but you’re not getting any speed, you’re not moving. So you’ve uncoupled the burning of the fuel in the engine with the movement of the car.

Earlier I mentioned that ketones help the muscle be more coupled. In that case, you’re revving the engine and you’re seeing movement with the speedometer. But with cold therapy, you’re uncoupling it where you’re revving the engine but you’re not moving anywhere.

Cold therapy is an incredible way to improve metabolism. Apple cider vinegar is also surprisingly effective. But you were asking about non-dietary approaches. So of all of those, I personally leverage whenever I can take advantage of cold immersion and sauna. They’re exceptional in this regard.

Circadian Rhythm and Blood Glucose

DAVE ASPREY: I do them a lot. The other thing that I notice has a big effect on my blood glucose stability, which is a proxy for insulin, is darkness at night. So I’ll wear the TrueDark glasses that trick the brain into thinking that it’s nighttime. And if I wear these for an hour or so before bed, especially if I’m traveling, I have much more stable blood glucose the next day. And I think it’s darkness at night to reinforce the rhythm. Work.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, it does work. Just to put a really clear statement on that, one of the reasons East Asians have such unexpectedly high levels of glucose is because these are cultures that have the highest bright blue light exposure later into the evening. That is one of the reasons.

There are some other quirks of physiology across ethnicities, but it is an absolute consistent feature of East Asian culture. Lots of bright blue light into all hours of the night, which absolutely will disrupt circadian rhythm to such a point that you’ll have higher cortisol levels the next morning and in turn higher glucose volatility.

Environmental Toxins and Insulin Resistance

DAVE ASPREY: Environmental toxins and insulin resistance. Is there a connection?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Oh, for sure, yeah. In fact, in my first book, you mentioned my “How Not to Get Sick,” which is this one over my shoulder. One step over outside of the camera is my “Why We Get Sick” book. I actually devoted a small section to, as I talked about the origins of insulin resistance, describe some of the evidence looking at certain molecules from plasticizer agents and detergent agents and more and more, even certain pesticides and herbicides.

DAVE ASPREY: Yes.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: So these are all chemicals that have varying direct or indirect effects at promoting insulin resistance. The direct effect is such like lectins have a direct effect as a kind of food anti-nutrient toxin. Lectins have a direct effect of causing insulin resistance, whereas some of the detergent molecules like diethylstilbestrol – it’s not going to have as much of a direct effect, but rather an indirect effect by promoting the growth of the fat cell.

And when fat cells grow too large, that comes back to the kind of slow insulin resistance that I alluded to earlier, where when the fat cell gets too big, it starts to generate its own form of insulin resistance. As an interesting aside, it actually starts to promote insulin resistance to try to prevent further growth, but in the process starts to kind of spread that insulin resistance with a couple different signals throughout the body.

So what we eat and drink and even breathe matters. Working with my colleague Dr. Paul Reynolds, we just published a paper late last year actually finding – this was an animal study – where when these animals were exposed to diesel exhaust particles, even when they ate the exact same amount of food as their litter mates just exposed to normal room air, their fat cells got significantly bigger.

So once again, our little rant earlier – don’t tell me it’s all about calories. There are these signals, even some things we breathe, that are going to influence the overall dynamic energy storage, the balance of metabolism.

Unfortunately, we live in a bit of a dirty world. Where people are able to mitigate some of these risks – now, I know that some people feel a little overwhelmed – I still firmly believe macros matter most. If you can just focus on one thing, focus on getting your macronutrients right.

Optimal Macronutrient Ratios

DAVE ASPREY: Give me the right ratios for macros.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, for me it’s very simply: control carbs. So don’t get your carbs from bags and boxes with barcodes as much as you can. Choose whole fruits and vegetables depending on your overall scenario. And then it’s prioritize protein and don’t fear the fat that comes with that protein and just don’t fear fat in general.

But as a reminder, in nature, all protein comes with fat. There’s no exception. So as much as we love protein, people talk about protein, there’s always a little part of me that says, and don’t forget about the fat that is supposed to come with that protein. The body digests it better. The combination of the two is more anabolic than just the protein alone.

So macros matter most and then all these other kind of more micro influences – that’s not to say they’re irrelevant, they matter. But thankfully if a person is eating fewer carbohydrates, that is the most offensive macronutrient source.

Proteins, depending on the source, can also be somewhat influenced and a little polluted, although animal proteins have much lower levels than plant proteins do. But even still, just as a person controls carbs, you end up inadvertently getting rid of things like the anti-nutrients. You’re going to get far fewer levels of pesticides and herbicides just as you’re eating less carbs, because those are the main vehicles for those kinds of things.

Whereas fats and proteins have generally gone through the animal and the animals cleaned out some of those things on their own, or they’re stored in other tissues that we don’t eat as much of. Certainly the muscle is going to be one of the cleaner tissues in the body.

So I would say, don’t expend all your energy depending on where you are at and what your financial capabilities are and your bandwidth to focus on this. If you are just managing your macros, you are, I believe, addressing the variable that matters most. But these other things do matter. But don’t let that overwhelm you would be my advice.

Seed Oils and Insulin Resistance

DAVE ASPREY: I like to outsource my liver and kidneys to cows.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: That’s right, yeah. Well said.

DAVE ASPREY: They pre-filter all of the plants for me so then I can eat them. And the results are profound when you do that. Or it can be sheep if you’re not into cows or whatever.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, ruminant meat. So if it’s a multi-polygastric animal, that to me is some of the best meat you can get.

DAVE ASPREY: So we’re aligned there. One of the potential causes of insulin resistance is excessive damaged omega-6 fats because they go into the cell membrane and they mess with things. How much of this is caused by carbs versus just eating all this combination granola, corn, soybean, and all those things?

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, so, Dave, you are putting me in a position where I am going to have… So I don’t mean for this to sound disparaging, in all sincerity. I don’t.

DAVE ASPREY: You can disparage me. Like, I’m curious.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Well, not you even. Not you. But when I say “seed oil crowd,” I don’t mean to put everyone in a little tribe here, but there are people who will say, “Ben focuses on carbs. Well, that’s not the real issue. It’s seed oils.”

I just want to remind people that my main focus is insulin resistance. It is not other problems. So within the direct realm of insulin resistance, I will claim that hyperinsulinemia is more of a problem than seed oils.

Now, at the same time, I want someone to know that if I’m actually talking about liver fibrosis, seed oils are actually probably more problematic. Cancer and damaged mitochondria that feeds cancer cells, seed oils are probably more problematic. So as much as it seems like I’m disrespecting the seed oil view, I actually am not. I’m just trying to kind of stay in my own lane where I really am kind of more of an expert.

DAVE ASPREY: I respect that greatly. And it’s possible that eating excessive seed oils contributes to insulin resistance because of cell membrane changes, but that’s not what you’re studying. You’re studying the effects of insulin directly on this.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah.

DAVE ASPREY: And so acknowledging what you’re an expert in and not going into areas that you haven’t studied, I can only respect that.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Good, yeah.

DAVE ASPREY: In my case, I think it’s advisable to minimize those. I haven’t eaten seed oils in a long time.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Totally agree. But let me answer the way you framed the question, because I do have thoughts on it. So the connection between seed oils and insulin resistance, I do not believe that it’s a direct effect.

DAVE ASPREY: Okay.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: For example, you can incubate cells with linoleic acid and they will not become insulin resistant.

DAVE ASPREY: That’s a pretty good piece of evidence.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, it is. And I want someone to hear, because I’ve literally done that. I’ve incubated cells with all kinds of stimuli, and then it’s a simple set of experiments. Now I’m going to incubate with some insulin for 10 minutes. I’m going to harvest those cells, and now I’m going to look at the signaling, the protein phosphorylation states across a handful of proteins. That will tell me, okay, how well did insulin work? So with a high degree of authority, I can tell you linoleic acid does not cause direct insulin resistance.

DAVE ASPREY: It’s fried for two weeks and then you do it.

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Okay, so now we’re not even putting on linoleic acid. So this is a really good point. If you start to just put on like the peroxides of this, that starts to change things. But just so people appreciate how difficult it is to work with these molecules, they are so reactive that they just become toxic – cytotoxic, where the cells just start to die. And so you can’t really even try to find the right dose; it’s actually problematic.

DAVE ASPREY: So the highest expression of insulin resistance is death?

The Impact of Linoleic Acid on Fat Cells

DR. BEN BIKMAN: Yeah, well, that’s right. I mean, so what if you’re insulin resistant, if you’re killing all your cells? So that’s a really, really good point. As much as I’ve just been talking about linoleic acid, the conversation really ought to be looking at the peroxides. That’s a really important consideration that I need to keep in mind.

Linoleic acid alone doesn’t appear to cause insulin resistance. The degree to which its peroxide metabolites do, I don’t know, but I bet it does. I bet there’s an effect there. But even still, the way I describe the relevance of linoleic acid is through what it does in the fat cell.

It takes me back to the fat cell, because linoleic acid is unique, that you can track it. If you eat more of it, you store more of it. And this has been shown in fat tissue from humans. When linoleic acid gets converted to these more reactive molecules like 4HNE in a fat cell, it forces the fat cell to grow through hypertrophy rather than proliferating through hyperplasia.

The difference there is that if you have more fat cells but they’re small, then you’re insulin sensitive from the level of the fat tissue at least. Because small fat cells are insulin sensitive and happy fat cells. They’re very anti-inflammatory as well. Linoleic acid converted to 4HNE, one of the more common reactive metabolites, tells the fat cell, “Hey, there’s no proliferation happening here. You’re just growing through hypertrophy.” The hypertrophic fat cell is an insulin resistant and pro-inflammatory fat cell.

So when I talk about linoleic acid or seed oils with some caution, I don’t like to say that they’re a direct cause of insulin resistance. Insulin is a direct cause. Inflammatory proteins are a direct cause. Like in that same cell culture, I can put on cytokines, they’re insulin resistant in minutes, stress hormones. I can incubate those cells with cortisol or epinephrine, they’ll become insulin resistant.

But if I do it with linoleic acid, like I said, it’s not quite the same effect. But with all of the myriad metabolites that can be generated, it is very possible that some of those could have a direct effect. But when I talk about it, I try to be a little cautious and just say, well, it might, but I don’t know if it’s direct, but I certainly believe it’s an indirect because of its effect on the fat cell.