Read the full transcript of a conversation between Bronwen Maddox and Dr S Jaishankar, External Affairs Minister of India, at Chatham House on March 5, 2025… on India’s Rise and Role in the World: A Conversation with Dr. S Jaishankar…

Listen to the audio version here:

TRANSCRIPT:

Introduction

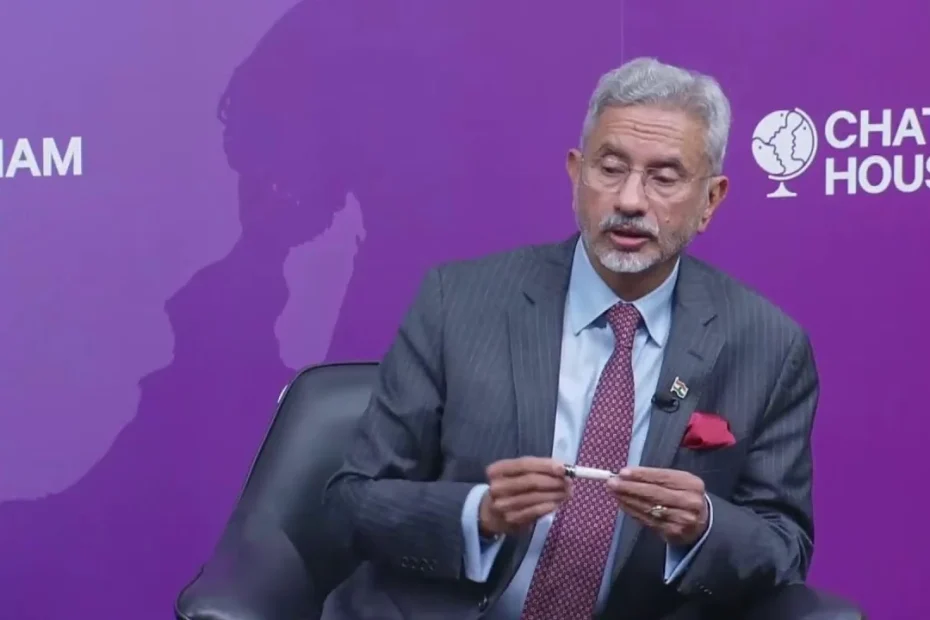

BRONWEN MADDOX: Thank you. A very warm welcome to Chatham House, everyone. I’m Bronwen Maddox. I’m the Director. And an extremely warm welcome to Dr. S Jaishankar, External Affairs Minister of India, who’s going to talk to us about India’s rise and role in the world.

He needs, I say this sometimes about our guests, but I will say that he needs no introduction. But let me just add a few things to the things that you will know about him. One of the, I’m going to say, longest standing foreign ministers around. He’s survived longer than many since 2019.

And he’s also a member of the Upper House of India’s parliament from Gujarat, was foreign secretary from 2015 to 2018, ambassador to the U.S., China, Singapore and the Czech Republic and has also served in other diplomatic assignments in Moscow, Colombo, Budapest and Tokyo. And I say that because people who have a span of the world are particularly valuable these days. And, we’re very, very glad that you have come here to talk about a wide range of things.

So I was saying to you upstairs, I want to start with geopolitics and then go on to some things about the British-Indian relationship and then come to some questions about India at the end.

Please, everyone, do start thinking of your questions. We’re going to chat for about half an hour, and we have a clean hour here. It is, just to make the point, on the record being recorded and live streamed.

U.S. Foreign Policy and India’s Position

BRONWEN MADDOX: So with that, welcome. Thank you. Let’s start with what we can call geopolitics, but that one word is standing for rather a lot these days. What do you make of the first forty-one days of the U.S. new foreign policy. Is it good for India? Is it good for the world?

DR S JAISHANKAR: Well, it’s interesting. And I think some of it, I must say, in all honesty, is not surprising. If you actually tracked it and assume that most of the time, political leaders at least do much of what they promised to do. They do not always succeed or they do not always get everything they want. But as a general principle, when political forces or political leaders have an agenda, and particularly if it is one which they have developed over a fairly long period of time and have been very articulate even passionate about it, then I think much of what we have seen and heard over the last few weeks was to be expected. So I’m a little surprised that people are surprised.

Now that said, is it good for India? In many ways, I would say yes. My prime minister was in Washington about two weeks ago. I had accompanied him. I was myself there for the presidential inauguration. And when I look at our interests and our expectations of the relationship, I think there’s a lot of promise we see there. Conceptually, I think we see a president and an administration, which in our parlance is moving towards multipolarity. And that is something which suits India.

BRONWEN MADDOX: When you say that they are moving towards multipolarity, do you mean accepting or even encouraging there being many poles of power in the world?

DR S JAISHANKAR: I think practicing and by practicing, promoting. Since 1945, one tends to think and talk about the United States as US and the Western world. So it’s more like a block rather than a nation. I think what is quite clear is the US’s own self-perception is now more as a nation and perhaps a little less as a block. Not entirely, you know, at one and not the other, but definitely the needle has moved in the direction of a more national personality and a more national analysis of its self-interest.

One looks at our own relationship politically, to be very honest with you, we’ve never had any issues with American presidents at least in recent times. There’s no baggage which we carry or burden that the relationship carries.

I think from President Trump’s perspective, the one big shared enterprise that we have is the Quad. And the Quad is an understanding where everybody pays their fair share. So there’s no spat about who’s paying for whom. There are no free riders in Quad. So that’s a good model which works, which was restarted during President Trump’s first time.

And if I were to look at some of the big priorities of this president, many of them actually work for us. He seems to be, for example, committed to keeping energy prices reasonably affordable and stable. We welcome that. He is putting a lot of emphasis on tech, on the development of tech, on the use of tech as a game changer in global politics. I think that offers a lot of possibilities for us. He appears open to connectivity initiatives of a certain collaborative nature. We have deep interest in that. So I would say and of course, he has a certain view of trade, as you may have—

BRONWEN MADDOX: I was sitting here thinking we’ve got this far without mentioning trade or indeed tariffs. And I was wondering where you thought India would come out, this tariff—

DR S JAISHANKAR: Yes, I was coming there, but probably.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Good. I’m just making sure we get—

DR S JAISHANKAR: We had a very open conversation about it. And the result of that conversation was that we agreed on the need for a bilateral trade agreement. And our trade minister, in fact, is there in Washington doing exactly that right now.

The West and Multipolarity

BRONWEN MADDOX: I was thinking as you were talking, the piece in the Financial Times by Martin Wolf this week saying the West is over. You think that’s right?

DR S JAISHANKAR: I wouldn’t put it so sharply. But I would say today, there are clearly—I mean, American interests are more sharply defined. And I suspect so are European interests. I’m not sure where exactly Britain is, probably non-aligned between the two. But it’s very clear—

BRONWEN MADDOX: It’s possible that it has not yet sharply defined its interest. But we might come on to Britain in a moment. But just staying with this picture, I would love to hear more about where India is going to position itself. Multipolarity, as you said. There is China. We still don’t know exactly what the U.S. might choose to do with China. It’s clearly bringing Russia a bit more in from the cold. Where is India going to put itself in this position? Vis-a-vis the U.S.? Vis-a-vis China?

DR S JAISHANKAR: All this is shifting. Our endeavor, at least for the last decade, has been to try to see if we can actually develop all the big relationships in a way and the non-big relationships as well. In parallel, we understand that each one of them is different. Sometimes the issues are different. And I mean I’m not saying that it means being equidistant or behaving the same with everyone.

I think in each case it has to be customized, it has to be assessed. And then you look at what are the advantages and what are the challenges and what are the benefits and what are the risks. And you arrive at a certain position or equilibrium. And if we can do that successfully with all the major powers and groupings, that actually puts you in a much better position in a world which we could see was heading towards multipolarity.

Think of it really as in a sense from what used to be said was a very bipolar world, which wasn’t entirely true. And then a unipolar, which also wasn’t entirely true. But today, if you have many more centers of decision making, many more sources of influence, many more discussions with multiple players to really address any solution or any situation. I think that’s the kind of world and I think the country which has some maximum flexibility and the least problems is obviously better off in that world, and that’s our endeavor.

BRONWEN MADDOX: It’s a really interesting point. I remember you saying on the platform at the Munich Security Conference, not this year, the big JD Vance year, but last year, you were on the platform with Antony Blinken, which seems a long time ago. And, you were saying, well, look, we’re going to trade with Russia to some extent, oil and to military support and we’ll trade with you. And he looked, meaning the US, and he looked startled at that. But that is the kind of flexibility you’re talking about.

DR S JAISHANKAR: I don’t think, to be fair to him, I don’t think he was startled. I mean, by that time, we’d been doing it for some time.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Yes. And I don’t know. Maybe not surprised, but still I’m going to stick with startled for the directness of your position.

DR S JAISHANKAR: Look, we’ve always been very honest about it. And I must say, even in 2022, we had discussed it at some length with the American administration. And I say this to their credit, they were also quite understanding about it because one issue which has been in a sense distorted the whole energy trade.

The fact is that after 2022, you did not want the Ukraine conflict to trigger a global energy crisis. We did not want to see global inflation and which meant that somebody had to buy Russian oil if the oil markets had to be kept at a decent at a reasonable price. So I think there was an understanding about the need for that.

And in fact, I remind people that was one of the reasons why there was a very conscious decision not to mix that trade with sanctions. So I think people have been very sober and very, I would say, sensible about insulating the global economy from that particular aspect. So we have been very honest about it because I would rather tell our partners and the rest of the world upfront what we are doing. I see no reason why we should be less than direct in any way.

BRICS and India’s Role in Global Conflicts

BRONWEN MADDOX: What about the BRICS? What would India like the BRICS to be? Economic grouping or ideological one? What’s the value of it going to be?

DR S JAISHANKAR: Look, it’s hard to put a label on it. And we all like putting labels. I mean that’s what we do for a profession. I mean that’s why you do what you do and I do what I do. But some things are not so easily defined, and BRICS is one for this reason.

I can’t say that it’s—I couldn’t put an ideological label on it in the sense if you look at the BRICS members, even the original members, we are a very diverse group. We are an exception to the normal rules on which groups are formed. I mean, normally, countries who approximate geographically to each other or have some particular shared history or some kind of ethnic or linguistic commonality. This is normally the basis to create a group.

Now BRICS defies all those assumptions. So it is not like the Commonwealth. It is not like NATO. It is not like the G7. It is not like anything which had been conceptualized early. What it had, I mean if I were to really look at what brought BRICS countries together, it was a sense among very major powers that they were not getting their due place or due share of global conversations and decision making. And they would be better off if they came together and then shall I say sent a collective message. So that is how BRICS started.

And since then I think clearly they must be doing something right if so many countries want to join BRICS and so many countries actually have joined BRICS. So we’ve had an expansion from the original four. South Africa joined, and then it has become a double digit membership in Joburg in 2023. And in 2024, last year in Kazan, we also added dialogue partners, the concept of dialogue partners. So the group has grown.

Yes, we do discuss economic issues. We also discuss political issues. It’s not like we—So I wouldn’t straightjacket it. I won’t as I said, it’s hard to find a single objective which would do BRICS justice.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Do you see a role for India in acting as an intermediary in any of these current conflicts? I’m thinking of the role that Saudi Arabia has taken on in at least bringing the U.S. and Russians together in Riyadh. India has been carefully not committed itself on Ukraine. But do you see a role for India in this?

DR S JAISHANKAR: I’m not sure. I’m not sure. I’ll only tell you what we have been doing so far. It would be hard for me to predict what could happen in the future. We have been one of the few countries who have been regularly talking to both Moscow and Kyiv at various levels.

My prime minister has been talking to President Putin and to President Zelenskyy. We have met with the presidents, the ministers, the national security advisers, the defense ministers. So and at various points of time, if there was a moment or an occasion when our weighing in was useful we have tried to do that. Mostly it has been very specific.

For example, in the summer of 2022, at that time, the Black Sea Green Corridor was sought to be constructed. And there were some hesitations in Russia. So a few other countries approached us including Turkey, which had the lead to press the Russians on that. We did that. When the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant came under firing, we actually were approached by the Ukrainians to pass messages on to the Russians, which we did, and they had something to say, which we communicated back.

# India’s Foreign Policy and International Relations

India’s Role in Global Diplomacy

DR S JAISHANKAR: We worked a little bit with Mr. Grossi in IAEA on that. So wherever there’s been a sense that India can do something, somebody has come to us and said, would you be willing to do that? We’ve always been open-minded about it. To the extent we preferred advice, we have largely done that in the privacy of a room.

We have spoken our mind to both countries, both leaders. Our view has been that they need to do direct negotiations. That’s been our consistent position. We have never advised them what should be the format and what should be the terms of the negotiations—that is their business. And I would say this, every time we’ve had a significant and useful conversation with either of them, we have taken the approval of President Putin to share this with the Ukrainians and President Zelenskyy to share it with the Russians.

So we have kept that going. But beyond that, as I said, we have never done a peace plan or put out a particular view. We don’t think that is appropriate. I think this is an issue where the parties involved have to decide for themselves.

And we also understand the stakes that Europe has in this matter. We understand the interest that the United States has in this matter. We hear it from the Russians that they too feel that there are other parties to be engaged. So I think we have done whatever was the right thing to do in the most helpful manner, and we’ll continue to do this.

UK-India Relations

BRONWEN MADDOX: Let’s come on to the relationship with the UK. You saw the Prime Minister yesterday. I believe you’re going to Belfast and Manchester tomorrow. You’ve seen David Lammy today. Is that right?

DR S JAISHANKAR: Yes. Was with him yesterday.

BRONWEN MADDOX: With the Investor Day as well. Lots of David Lammy. Right. Where does this stand? And let’s start with the free trade agreement. I was in fact, the last time I saw you in your office in Delhi eighteen months ago, and there was a great buzz around, was there going to be signing of the deal then? Would Rishi Sunak come over? Could he tuck in the cricket as well? There’s a whole fuss around it. Then eighteen months goes on. Is it intellectual property on pharmaceuticals? Is it visas again? Where is this?

DR S JAISHANKAR: I think some progress has been made in the negotiations. I mean, first of all, let’s understand this is a negotiation. And it’s a serious negotiation because when you do an FTA, you’re really locking in your country into a long-term arrangement with another partner. So you don’t do that in a hurry. You don’t do that frivolously.

So there is a lot of homework. There are a lot of forward projections made of what are the benefits and what are the costs. So it’s a fairly complicated process. It’s not just like going to a shop and buying something. So given the complexity, to me, it’s natural that it would take—

BRONWEN MADDOX: We were discussing upstairs, though, how this can burn up decades of people’s lives.

DR S JAISHANKAR: Well, I’m not sure I think it should take decades. I mean, with the EU, we are into our third decade. It’s not an experience I recommend to anybody else. But we would like to accelerate this. I got a clear message.

I also met Secretary Reynolds. So I think from Prime Minister Starmer, from Foreign Secretary Lammy, from Secretary Reynolds, I got a consistent message from all of them that the British side is also interested in moving it forward. We had a round last month in February in Delhi when Secretary Reynolds was there. We remain in touch. I had a few points to convey on behalf of my concerned colleagues as well.

So I am cautiously optimistic that the pace will quicken. Hard to say when it would come to head, but I certainly would hope that it doesn’t take that long.

BRONWEN MADDOX: And in the broader relationship with the UK, how do you see that changing?

DR S JAISHANKAR: Well, look, if we actually do conclude the FTA, which I’m optimistic about, I think it will have not just economic or a trade impact. I think it would have a larger relationship impact. I think people will see many—they would be encouraged to explore a lot of other possibilities. And there are possibilities.

I’ll give you an example. We’ve had a British university actually open a campus in India. Now that’s a big deal. It’s a big deal because when we have a few successful cases, these numbers would grow. Now we’ve allowed foreign universities. We’ve opened up the education sector to foreign universities fairly recently.

And if you look at the numbers, I mean we have today about a million plus, maybe a million and a quarter Indian students studying abroad at any given time. There would be at least twice that number of people who would have been interested and had they had an opportunity would have liked to explore that. And in addition to that, there would be many others if they saw instead of them going out, they actually saw the universities coming to their homes or close by, they might be interested as well. So I can think of the education sector as a completely new area which would open up.

So when you have something momentous happen in a relationship, I think it will have a ripple impact on a whole lot of other sectors. I see that similarly, we are considering making some significant changes to our nuclear policy, including amending our liability legislation and also contemplating the possibility of private sector operators in the nuclear field. Now that too is a potential area of collaboration.

Could give you a whole lot of areas. Now I think many of these are waiting to happen. We need something like an FTA would provide that sort of tailwind.

BRONWEN MADDOX: It would be quite wrong for me to ask you in detail everything the Prime Minister said. But nonetheless, what is the stumbling block at this point on the FTA?

DR S JAISHANKAR: And there is no such stumbling block. Look, if there are negotiations sector by sector, I mean, let me say this, I mean, pretty much everything I have read about the FTA in the press is inaccurate.

BRONWEN MADDOX: So Visa not a problem. Pharmaceutical IP is not a problem.

DR S JAISHANKAR: Excuse me, you asked me that. Visas have nothing to do with FTA. I mean the only visas the FTA is concerned with are the visas for intracorporate transferees, business people going to take up jobs in their particular branch of the same business. So I saw these stories or these reports that somewhere there are visa demands. That’s not the case. And I could give you a whole lot of other inaccurate examples.

So look, it’s not that there’s some big boulder out there which we need to get out of the way. I think these are painstaking negotiations. And they are painstaking because as I said, these are serious commitments which are being made, which have economic consequences, which will affect the lives of people in a way. So I think there is a sense of responsibility with which negotiators go about that business.

India’s Economic Growth and Demographics

BRONWEN MADDOX: Thanks very much indeed for that. Let me just ask you a couple of things before we go to wider questions. So a couple of things about India itself. And I’m very struck by a whole line of discussion in the Indian media at the moment, summarized by the question, will India get old before it gets rich? Not the country so much as its people, but the question of whether its growth is really managing to keep up with the aging and size of the population.

DR S JAISHANKAR: That’s not a question which is unique to India. I mean people have been asking that question on China. They ask it about some other nations. They ask you about this one too, but yes.

So I think it’s a natural question to ask about any economy which is growing rapidly and which is consequential for the rest of the world. My sense is the pace of progress in India, I mean, is just me talking, will actually surprise people because we have—I mean, look at it today, we are roughly, I would say, about three thousand dollars per capita economy, okay? Think back on the rest of the world when it was at that level.

What is different for us is we have the access to technologies and practices and possibilities which others at that point did not have, for example digital. So there is a great possibility to leapfrog in terms of our development. And I think I’m pretty sure that the growth of India will follow a pathway or a trajectory which would not be taken by any significant economy before us simply because many of those possibilities did not exist for those economies at that time.

BRONWEN MADDOX: I press you on it because so much hope has been attached to India’s development, its trajectory, as you said. And yet there are a lot of questions about whether that can continue or, as you said, leapfrog.

DR S JAISHANKAR: Look, again, I don’t think any of us doubt that it will continue. I mean we are fairly sanguine that we have multiple decades of growth at, let’s say, seven percent ahead of us. But naturally with urbanization, with prosperity, there are demographic consequences to that. That’s a universal rule.

Why would we be an exception to that rule? But I think if you look at the numbers, I think there will be a demographic trajectory. There will be a prosperity trajectory. I am not sure that there is grounds to be as alarmed as your observation would suggest.

Minorities in India

BRONWEN MADDOX: Thank you. We might come back to that in the questions. Let me just ask you one more, something that comes up in parts of the certainly with the British media with parts of the British government about whether India is still a place where minorities feel that they can thrive. The argument being, look, it’s great if you’re part of the Hindu majority, but becoming a less comfortable place if you’re Muslim, Tamil, Sikh, whatever. Does that come up in your conversations with Britain? What is your answer to it?

DR S JAISHANKAR: I’m a Tamil. I feel completely comfortable. And I think I can say that for the high commissioner too.

So look, there is a politics prevalent in some parts of the world. Very driven by a kind of a vote bank consideration, very driven by creating identity lobbies, actually pandering to them, stalking a certain attitude. And we don’t think actually that’s very healthy politics.

So if the idea of good politics is good politics is all about how do I look after cater to minority demands. I think to me good politics is actually about treating your citizens equally. And when I look at the last ten years and I see many of the big transformations on the way, let us say, housing entitlements, loan entitlements, business entitlements. I think as a polity, we’ve been very, very fair.

And to me, that kind of tokenism is actually very destructive politics. So I would actually dispute the idea that somewhere that’s an ideal to which we should all aspire. I think that is a model which we actually reject.

BRONWEN MADDOX: On that note, let’s go to wider questions. I don’t know if the question will come up again, but thank you.

Q&A Session

BRONWEN MADDOX: Forest of hands up immediately. Let me start at this far side. I’m going to take two at a time, Please. And could you wait for a microphone to come and please identify yourself as well?

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] My name is Shelby. I’m a journalist from South China Morning Post. So my question is will Modi come to attend a SCO conference in China this year? And as of currently, there’s no direct flights between China and India, it’s very difficult to get visa. And as of China and India are having very few journalists on in the ground in each other’s country, and how and when will those issues be resolved?

BRONWEN MADDOX: This is about direct travel. All right. Do you want to answer that one? Let me just sum up that question. You asked me on flights, on visas and journalists? And also would Modi be there for the SCO?

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] Yes.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Could I take one more? Yes. Go in the middle. Yes, you.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] Sachin Ravikumar with Reuters. In the context of Europe trying to boost its defense capabilities, would India’s defense industry have a role to play in bolstering those capabilities? And is this something you would be promoting in the coming weeks and months? And secondly, if I may, vis-a-vis trade with the U.S., would India be open to lowering tariffs on car imports?

BRONWEN MADDOX: You’ve knocked past my usual guard of saying only one question, but you’ve got two in, which were Defense and Cars.

DR S JAISHANKAR: She got three in.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Yes. We’re going to go to one question rule.

DR S JAISHANKAR: So on the first question, look, there was a certain context for why relations between India and China were disrupted. And the context was what China did along the line of actual control in 2020 and the situation which continued after that. Now in October 2023, we were able to resolve many of the urgent issues, the pending issues pertaining to that what we call disengagement of troops who had been deployed upfront.

So after that, there was a meeting between Prime Minister Modi and President Xi in Kazan. And I myself have met Foreign Minister Wang Yi, our National Security Advisor and our Foreign Secretary have visited China. And we are discussing with China some steps to see how the relationship can go in a more predictable and stable and positive direction.

One of the steps which you did not mention, so let me do your three questions add a fourth one, which was the resumption of pilgrimage to Mount Kailash, which is in Tibet, which Hindu pilgrims have been going to for ages. So the resumption of pilgrimage, direct flights between the two countries, the journalist issues, all these are being discussed. But there are some other issues. For example, we had a mechanism about transborder rivers that mechanism had stopped to meet because the relationship was very badly disrupted after 2020.

# India’s Foreign Policy Perspectives

India-US Defense and Trade Relations

DR S JAISHANKAR: So we are looking at this package. I think people tasked with that mandate are dealing with each other. It’s hard obviously we would like to see it done sooner rather than later and then we will see what happens after that.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Your question: Can Indian defense industry profit from your new need for defense?

DR S JAISHANKAR: We have a substantial Indian state-owned defense industry but also now a growing Indian private sector defense industry.

They are global in their interests and aspirations. Even the state-owned ones, these are enterprises. They make the decisions depending on where there’s demand and what the market opportunities are. Normally, leave it to them to make the business, the corporate decisions that they should unless our national interest or our security interests are involved in some way. So I think if some of them wish to look at demands in Europe, I think that is a business decision that they should be taking.

On the issue of tariffs, as I said, we have understanding that we would be negotiating a bilateral trade agreement with the United States. So that process would unfold. Our trade ministers, they’re holding discussions right now. So one has to see where that goes.

Questions from the Audience

BRONWEN MADDOX: Another forest of hands. Right. I’m going to take the woman on the aisle there.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] My name is Palmosha. And I wanted to ask about you mentioned BRICS and India’s role in BRICS. Do you see India’s role in the Middle East because you spoke about Ukraine. Well, what about the Middle East in specific to Gaza?

BRONWEN MADDOX: Thank you very much. Here in the front, Chitish. I’m going to take three this time.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] Shitej Bachpe, Senior Research Fellow for South Asia at Chatham House. Many thanks for your very insightful remarks. I had a question about India’s neighborhood. India resides in a region in which three countries are in the midst of IMF bailouts, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Two countries could be regarded as potentially near failed states, Myanmar and Afghanistan and two countries with which India has a history of difficult relations, which also happen to be nuclear weapon states and it also has active territorial disputes, of course, I’m referring to China and Pakistan. You also have a relatively low level of regional economic integration and institutional integration, at least compared to other regions in terms of intra-regional trade. So my question is: do developments in India’s neighborhood hold back or undermine India’s global aspirations? Or to put it more bluntly, can India rise without its region?

BRONWEN MADDOX: Thank you. And I’m going to take one more right here in the front.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] Thank you very much. I’m David Lube, I’m an economist here at Chatham House. I wonder if you could comment on India’s aspirations for the internationalization of the rupee or more generally, you and the Indian government have a problem with dollar dominance in the international monetary system?

BRONWEN MADDOX: Great. Thank you. We have the Middle East, Gaza. We have whether India can rise without its neighborhood, without relations with its neighborhood and the internationalization of the rupee.

India’s Role in the Middle East

DR S JAISHANKAR: On the Middle East, obviously, we have significant interest. I mean, depending on how you define the Middle East, if you were to include the Gulf in it, we would have more than ten million Indians actually living there.

Our trade with the Gulf would be today our exports to the Gulf alone would be close to one hundred billion dollars. Our trade with the Mediterranean is close to eighty-five billion dollars. The Mediterranean has almost zero five million Indians living in the littoral states of the Mediterranean.

So if I were to look at the footprint, the economic footprint, I mean, whether it’s the Mediterranean countries, whether it’s the MENA countries, whether it’s the Gulf, there isn’t a country where there isn’t today some kind of significant Indian project, business, infrastructure activity. So yes, we would like to see a stable, safe, prosperous Middle East, but we do understand. I mean right now the situation is very complicated.

Again, we have a position which is obviously in my view very objective and balanced. We do condemn terrorism and hostage taking. We do believe that countries have a right to respond to that but we also believe that humanitarian law should be observed when undertaking operations. We do think there is an urgent need to get relief and rehabilitation done in Gaza. And we strongly advocate for a two-state solution. So we have, I would say, a broad spectrum but consistent and in our view an objective position about it.

Again, if there is a – and Indian peacekeepers by the way are deployed today both in Lebanon and in Golan Heights. So if there is some way or something we should be doing, we are open to looking at it. We have been engaging pretty much all the players, Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf countries on that. So our sense right now is really it’s largely the countries in the region who have the initiative and the United States. So if there are countries who have that initiative and doing something, it’s good that they are doing something. But our interests are that there is some kind of lasting solution found to the crisis.

India’s Neighborhood Relations

On your question, Shitej, about the neighborhood, again there are a lot of things happening on the ground. This may or may not fit into a theoretical construct. For example, if one looks at connectivity, and by connectivity I am talking here of roads, of waterways, of electricity grid connections, of fuel supplies, of movement of people. In fact, the last ten years has seen an extraordinary pickup that whether it is Bangladesh, whether it is Nepal, even Myanmar that every one of these countries today in some form compared to where they were five or ten years ago are either importing or exporting more energy, are trading more, are seeing a much greater flow of wagons, buses, people, you name it, much more goods transiting through countries or to countries.

So in many ways, actually, on the ground, the real economy is experiencing a very, very profound change. Now in terms of regionalization, perhaps in a sort of conceptual way, it may not be that visible. But then do bear in mind when Sri Lanka had a very serious financial crisis, while the rest of the world largely sat on its hands, we actually came forward with a package of more than four billion dollars which was almost twice the size of the IMF package.

And if you rewind a bit and look even at COVID, that region, like any other region, has had a COVID crisis. It’s had a Ukraine crisis fallout. There have been issues coming out of the global economy because it relates to your question about availability of dollar, trade issues, liquidity crisis, we’ve actually stepped forward for pretty much every neighboring country, whether it was supply of vaccines, whether it was supply of food grains, whether it was supply of fertilizers, supply of fuel. And as I said in Sri Lanka, actually a huge economic package.

So we do see today a regional responsibility. We do believe that our neighbors must do well and that their prosperity and our prosperity are linked. We think our own growth could be a lifting tide for the rest of them.

But while we are a larger economy and by and large we are generous and non-reciprocal, we have interest like any nation. So we also expect our neighbors to recognize that and to cater to our sensitivities as well. So I am not saying that it has to be an equal give and take, but there are gives and takes. And I think just like we have a responsibility to our neighbors, I think our neighbors also have a responsibility to us.

Internationalization of the Rupee

The third question, the rupee. We are clearly promoting the internationalization of the rupee for the very simple reason that we are actually promoting the globalization of India.

There are more Indians who travel out. There are more Indians who live abroad. India’s trade, India’s investments, India’s tourists have all grown. So along with that, the practice of using rupee will also grow. So in many cases, for example, we have established mechanisms for cashless payments between India and some other country.

We have, in certain cases, supported trade settlements, but we have also supported trade settlements because there is a shortage of hard currency in many countries, especially of dollars. So in a way there is a steady, I would say, externalization of rupee transactions that’s part of the globalization of India.

But where the role of the dollar is concerned, I think we are very realistic about it. We have never had a problem with the dollar. Our relations with the U.S. are probably the best ever that they have been. So we have absolutely no interest in undermining the dollar at all. On the contrary, I think a lot of the problems in our region is the lack of the availability of dollars. So I would say many countries want to see more dollar, not less.

More Questions from the Audience

BRONWEN MADDOX: Thank you. Take a gentleman here on the aisle. Yep.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] My name is Nisar. I am an author and a journalist. Let me make you a little nervous, Your Excellency. Thank you very much for your dissertation. Kashmiris are up in arms because India is occupying Kashmir illegally. That’s the reason why they are protesting. Given Donald Trump’s zeal for striking peace deals, can Narendra Modi use his friendship with Donald Trump to solve out the problem of Kashmir? There are one million soldiers stationed in Kashmir to control seven million Kashmiris. So what are you going to do about the Kashmir problem? You haven’t spoken about it.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Can we just capture the question there? Thank you. And there was a similar one from Naomi Canton of The Times of India pegged to the debate in the UK Parliament today mentioning Kashmir. All right. Kashmir, what are you going to do to solve it?

Woman on the aisle in black and white, I think.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] Thank you. I’m Vedika, and I am a student at King’s College London studying international relations. So my question is that when we talk about Global South aspirations and at the same time, we talk about India and China’s rivalry. So sometimes, because of this rivalry, the Global South aspirations are somehow diluted. Do you think this rivalry can sort of reduce the impact of the Global South in the larger context? And what measures can Indian foreign policy and the decision makers take to make sure that this does not happen.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Thank you very much indeed. And let me add one from online. Ishan Devala, do you see an opportunity for better relations with China in a multipolar world, which relates to that last one.

Everyone online, you’re asking terrific questions, but they’re really long. They look a bit like essays. Really good points. That was a nice short one. We have Kashmir. What are you going to do to solve it? We have Global South losing impact or not, diluted impact or not. And we have détente, the word used with China.

On Kashmir, Global South, and China Relations

DR S JAISHANKAR: Okay. Look, on Kashmir, actually, we have done, I think, a good job solving most of it. I think removing Article 370 was one step number one. Then restoring growth and economic activity and social justice in Kashmir was step number two. Holding elections, which were done with a very high turnout, was step number three. I think the part we are waiting for is the return of the stolen part of Kashmir, which is under illegal Pakistani occupation. When that’s done, I assure you, Kashmir is solved.

The second question, Global South. You know, look, there are different ways of looking at it, and I give you a perspective. What do countries in Global South largely want? They want more options. They want more experiences to compare relatable experiences. They would like to get into relationships which actually help them build their society on a sustainable basis.

So forget India or China for a moment. I think what is happening is that much of the Global South in the previous decades had very limited options. They either had western options or they had multilateral development banks which were in a way associated with it. Within the western options they had maybe some subsets out there. Then over at some point, they had Soviet/Russian options. Then you had a set of China options.

Now today, if there are Indian options, I would argue that actually it is better for the Global South. It’s not worse because they now have many more possibilities to choose from. They will be in a position to evaluate which of these options and which of these relationships somewhere fit into their growth aspirations.

And I can certainly say where India is concerned we have today projects in almost eighty countries of the Global South. We have delivered actually about six hundred significant projects in the last many years. And I do think that by doing so, I mean obviously the partner country is benefited, but it also strengthens the hands of the partner country dealing with other relationships.

So I would not put this negatively at all. In fact just like I say for India’s positioning a multipolar world is helpful. I think for Global South as well a multipolar world is helpful and it actually increases their negotiating ability.

The last question, what kind of relationship we want with China? Look, we actually have, by any standards, a very, very unique relationship. I mean, first of all, we are the only two billion plus populated countries in the world. We have, both of us, a very long history. We’ve had the ups and downs in our history. You have today both countries on an upward trajectory.

And here’s the challenge. And it so happens we are actually direct neighbors. So the challenge is this that when any country rises, its balances with the world and with its neighbors obviously change.

India’s Global Perspective and Foreign Policy Challenges

DR S JAISHANKAR: Now when two countries of this size, this history, this complexity, this consequence rise broadly in parallel and obviously they have an interplay with each other. I think the issue is how do you create stable equilibriums and then transition into the next set of equilibriums or next phase of equilibriums. We want a stable relationship, but we want a relationship where our interests are respected, where our sensitivities are recognized, where it works for both of us. So I think that is really been the challenge in the relationship.

And obviously, for us because of the border, the management of the border is crucial. The assumption for the last forty years has been that there must be peace and tranquility in the border areas if the relationship is to grow. If the border is unstable or is not peaceful or is not tranquil, obviously, it will have consequences on the growth and direction of the relationship.

Q&A Session

BRONWEN MADDOX: Okay. Let’s just squeeze in a few more hands. All right. I’m going to sit here. The gentleman right in the middle who’s been very patient.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION]: Anish Nase, retired banker. Dr. Jaishankar, one huge question for you. A lot of talk has been emanating from BRICS group to replace dollar and have its own payment system. Do you think in view of fast changing demographic in respect of politics and economics, is this likely to happen in the next five, ten years? Thank you very much.

BRONWEN MADDOX: I’m going to go to Ashish Goyal right on the aisle here. Ashish, if you can wait for a microphone to come to you, which is coming now. You got it. Brilliant.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION]: Thank you, Dr. Jaishankar, for your thoughts. I’m Ashish Goyal. I’m a global macro investor. I’m going to continue on this dollar theme actually because you spoke about the idea of multipolarity being a good thing, and that’s where we are headed towards. So why not multipolarity of the dollar as in, in the sense, currencies across the world, payment systems across the world?

And just one perspective is that if the US did not have the dollar reserve status, by now, you would have trashed the currency because look at the fiscal deficit, look at their external deficit, all of that. So I understand that that’s been the stable guiding force for the last eight years. But I think going forward, India needs to prepare itself for a multipolar world even in the dollar settlement system or the currency system in the world. So would love to hear your thoughts on that.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Okay. There’s those two. And then I’m going to just take a different tack because there really are quite a lot online about human rights. I’m going to say from Hamed Safraaz saying, and he’s speaking for many here online, “India has positioned itself as the world’s largest democracy, but concerns about its human rights record have been growing.” The statement, how does India plan to address this issue? Does it acknowledge any shortcomings? And there are various others in that line, Shahid Ahmed as well. There is a cluster.

So we have dollar, and we have human rights. I could take a few more.

DR S JAISHANKAR: I could take a few more because my answers would be pretty short on both.

BRONWEN MADDOX: You don’t know what I might then say. I will take this gentleman on the aisle then.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION]: Hello. I’m Bhanu Pranav, and I’m studying theoretical physics in King’s College London. So my question is in that direction, in education and especially in the pure sciences. I’ve always aspired to be back home but receive international level education. So what are your thoughts on us reaching out into the world more accessibly and India becoming a center for global level research, especially in the Pure Sciences.

BRONWEN MADDOX: Let’s take those because we need to stop at seven. Thank you for your generosity, but we actually respect the time. So we can close with this, right?

On Global Currency and Dollar Dominance

DR S JAISHANKAR: I’ll take the two dollar questions together. First of all, I don’t think there’s any policy on our part to replace the dollar. As I said, at the end of the day, the dollar as the reserve currency is the source of international economic stability. And right now, what we want in the world is more economic stability, not less.

I would also say in all honesty, I don’t think there is a unified BRICS position on this. I think BRICS members—and now that we have more members—have very diverse positions on this matter. So the suggestion or the assumption that somewhere there’s a united BRICS position against the dollar, I think, is not borne out by facts.

And again, to me, it’s kind of deterministic that if there is multipolarity, multipolarity has to translate itself into a currency multipolarity. It doesn’t have to. Again, even when I was explaining multipolarity, my point was that if there are multiple players, it’s not that India’s relationship with each player is the same. There are different considerations in each relationship.

For us right now, we think that the United States has really, in many ways, clearly the largest economy in the world. In many ways, almost the fulcrum or the key player in the global international architecture. Our own relationship is growing. It’s very positive. We do believe today that working with the United States and strengthening the international financial system, economic system is actually what should be the priority.

So I think that both a strategic assessment as well as our sense of what is required today by the international economy will really guide our thinking on this matter.

On Human Rights Concerns

On the human rights concerns, I think a lot of this is political. It is political because we have—Political is not necessarily a bad word. I mean, it’s how people express their desires for their country.

Allow me to complete. We have been, for political reasons, at the receiving end of a lot of, I would say, expressions and sometimes even campaigns on human rights. We listen to it. If we are not perfect, nobody is perfect. There can be situations which require redressal and remedy.

But I would actually argue that if one looks around the world to be very honest, I think we have a very strong human rights record. We as a democracy, as a credible democracy where people still have faith and in fact growing faith in that democracy, where actually representation has broadened in every conceivable way over the last many decades, where the state has been very fair in terms of treatment of its citizens. I think any sort of sweeping concern on human rights is really misplaced. Don’t see justification for it at all.

On Research and Innovation in India

And the last question on global level research. Today, there is a big spurt, I would say, in the innovation culture, in the startup culture in India. We also have a lot of global capability centers. In fact, I think about forty percent of them globally are actually located in India.

My sense is in the coming, say, five years, I actually expect to see both at an enterprise level as well as in terms of our own entrepreneurial tendency. I expect to see a much more energetic innovation and research culture. This is quite apart from what the government is doing. We have set up national research foundation. There is a much greater push for various enterprises and agencies to invest more in research.

There are some standout sectors. Space would clearly be one where you can see really what has been a very youth-driven, often almost outside the government innovation which has paralleled what have been enormous steps taken by the government-led program as well. But it’s happening in a whole lot of other areas. And I think for young people in India today, there are possibilities and opportunities out there, which probably didn’t exist in the previous decade.

BRONWEN MADDOX: We are going to have to stop there. There was a forest of hands up. There are loads of great questions online, very few which I could squeeze in, but many of them are thought provoking, some of them charming. I’m looking at Raghu Ramachandran saying, “What is your personal desire or vision for the world in the next twenty-five years,” which I didn’t bring in. Might have to wait for your next book. Everyone, can you join me in thanking Dr. Jaishankar.

Related Posts

- Transcript: Trump-Mamdani Meeting And Q&A At Oval Office

- Transcript: I Know Why Epstein Refused to Expose Trump: Michael Wolff on Inside Trump’s Head

- Transcript: WHY Wage Their War For Them? Trump Strikes Venezuela Boats – Piers Morgan Uncensored

- Transcript: Israel First Meltdown and the Future of the America First Movement: Tucker Carlson

- Transcript: Trump’s Address at Arlington National Cemetery on Veterans Day