Read the full transcript of neuroscientist Dr Iain McGilchrist’s lecture titled “The Sovereignty of Truth” on Saturday 26th October 2024 at the Royal Institution, Mayfair.

Listen to the audio version here:

TRANSCRIPT:

Introduction

DR. IAIN MCGILCHRIST: Well, thank you very much. Thank you for those words of introduction. And thank you for your welcoming applause.

I’m very aware that we are facing a real crisis, and I feel my fragility, my weakness, really, in having anything useful to say about this. I’ve put together some thoughts about the importance of truth, and I’ll try and convey as much as I can in the time that I have. In a way, this is my “il pensoroso,” and the other lecture will be “l’allegro,” because in this one I’m putting forward the shadow side, and in the other I’m hoping to put forward a much more hopeful side.

So don’t cut your throats before you’ve heard the after-lunch talk. I read yesterday that almost a third of young French people have lost faith in democracy, according to a poll. Why? I think the roots go deep, and we’re no longer remotely what we were born to be.

The Diminished Human

Emerson, as it happens, we didn’t confer, said in his 1836 book Nature, a very profound and interesting book, “Man is a dwarf of himself.” What did he mean by that? What he meant was that we are destined to, we have the potential to, achieve a really important role in the cosmos, not just for ourselves, but for the existence of what is good, beautiful, and true. And in my lifetime, I’ve seen each of these important transcendental values sidelined, decried, debased, destroyed.

Why is there life at all? Well, I’m not going to say much about this now. I’ll say something more about it in the second talk I give today.

And now, of course, there is an attack on all three, and I’m mainly going to be talking about truth for now. I think the sheer trashiness of our culture is killing us. It is distracting us from everything that is important.

Every time somebody tries to raise a question that is really important, it is dismissed, ironized, or becomes the object of some kind of political targetry. And it’s not just that we’re distracted from truth, but we demand protection from truth, in case it hurts us, in case life hurts us. We’ll grow up and live, because life is tough.

Everybody’s life is tough. Life is a challenge, a challenge we should rise to. We are resilient.

We have in us resilience. And yet we are all the time being encouraged to think about what we believe might have determined us in the past, and so we are traumatized and of no use. But instead, I think we should think of what we will allow ourselves to be drawn towards in the future, which is all we have to mold our own and that of humanity.

A Culture of Lies

We live in a lying culture in so many ways. In government, in the universities, alas, and across a whole range of public debate, mediated by social media, of course, at its worst, but even by the once trustable sources of integrity, which seem to have become partisan. I was very struck by a book I read in 1978, when it was first published, called Lying, and it’s by Sissela Bok, a philosopher, and she talks about lying and deception of all kinds in public and private life, across government, medicine, law, academia, journalism, in the family and between friends.

And she rather controversially argues that there are no situations, and I think she’s wrong about this, but there are no situations in which a lie can be excused. I think a better way of putting it is that the price of lying is enormously high, and that only the most extreme circumstances make a lie justifiable. We can’t live by lies.

And this is the book, simply entitled Lying, and it’s still in print. But actually, eight years before, I had heard what David had referred to, Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech. He was a man who had been tortured, imprisoned, subjected to inhuman circumstances, and wasn’t allowed to go and receive his Nobel Prize, but his lecture was read for him.

And I remember hearing it through the radio in the kitchen, and I was completely electrified. I’d never heard anything like this. Not that I had an education that wasn’t interested in morality and in philosophy and in the face of humanity, but the urgency of the way in which he described the importance of truth struck me very deeply and has never left me.

The Power of Truth

There is the man. Interestingly and amusingly, when you go looking for pictures on the Internet, and I did go looking for this picture, when you download it for a slide, a little thing at the bottom, a little bar pops up, alt text, something like this, and it says, “person with beard.” And there we are.

This is the book. I have this little pamphlet. I’m sure it’s been reproduced, but his quotation was of a Russian proverb, “One word of truth outweighs the whole world.”

I want you to think about that, because at the end of my second talk, I’m going to talk about what we can do. And one of the things that people are downfounded by is, I’m so small, and it is so big, what impact can I have? I think the answer is, you can have an enormous impact locally, but I don’t want to anticipate what I’m going to say later. And then, of course, there’s another person with beard.

It doesn’t dare say a man with a beard, but a person with a beard. And this, of course, is Fyodor Dostoevsky. And amongst many things that he had to say was, “Above all, do not lie to yourself.”

And it’s a very important point, because the point that he makes is, and I hope you can see the text up there. I can’t actually see it to read it, but you can read it yourselves. It’s rather annoying when a lecturer puts up a text and starts reading it to you.

So read it and take it in. But the point that he is making is that when you lie to yourself, you become less than human, and your relations with others are falsified, debased, and that ultimately the reason for not lying to yourself is love. Without truth, we cannot trust.

Those words, of course, are cognate in their origin. And without trust, we cannot love. But we live, above all, in an age in which we don’t know what or who to trust.

Truth, Trust, and Belief

Truth and trust are central, and they are related to belief. Because when we say true, we are really analogizing with the relationship. Everything in the cosmos, everything is relational.

In the matter of things, I argue, and I’m not alone in this. Fortunately, physicists say this, that relations are prior to relata, the things that are related. And that sounds very odd to our mind.

How can there be relations if there aren’t already things to relate? But, of course, those things only become things because of the web of relations that they’re in. You are only you because of the context of everything else that you experience and the society in which you grow up and to which you hope, I hope, to give back. And beliefs are like this, too.

The root of belief is Lieben in German, and we had the word Lief in Elizabethan English. So Shakespeare will have a character say, “My Lief, Lord, my dear Lord,” whatever it is. Now, belief is, and the German word Glauben, which means to believe, is also rooted in Liebe, love.

And what one is saying is not that I can prove that this thing is true in a kind of laboratory sense, but I give it my fidelity, I give it my trust. I place my trust, my truth in it. Unfortunately, a lot of people approach religions as though they were a sort of test in how many impossible things you can assent to before breakfast.

But that’s not really, it’s not really a matter of propositions, although it’s often put in that way. It’s a matter of dispositions. And this is actually a difference between the left hemisphere state.

I want to have this absolutely black and white. What is the truth here? And the truth is a thing that you can find by following steps. And the right hemisphere sense that it is a relationship.

It is one of trust, but that trust is not blind. It’s no more blind than if you are fording a stream, and someone on the other side reaches out a hand to you. You don’t take a blind leap of faith.

You answer to the hand that is stretched towards you.

Beauty and Truth

Dostoevsky also said “The world will be saved by beauty.” And that’s a puzzling saying.

How could the world be saved by beauty? Beauty is, is it not somehow an add-on? Well, I don’t think it is. I think it’s at the core of everything that matters. And what he meant, I think, is that though truth can be debased, good can be produced.

It can be turned into following a certain doctrine, assenting to certain approved beliefs. But that is not being good. Good comes from the heart. And so it resists the lie. The beautiful cannot be faked. And whatever certain artists now claim their work shows, that is not what art is doing.

Art is bringing into being for us, in a metaphorical sense, a beautiful truth which the soul immediately recognizes. Cognition is bypassed. And it’s through our ability to distort cognition that we are misunderstanding truth and misunderstanding goodness.

Interestingly, I think utilitarianism is, although it’s very fashionable in philosophical faculties and in universities, is the quintessentially corrupt way of estimating good, doing a calculus. But that calculating mind is exactly the mind that goodness calls us to lay aside. So we in the West have descended into utter mediocrity, I believe, as a result of the ways we’ve just dismissed goodness, beauty and truth in recent years.

But no, this is not just another attack on the West, but to point out how it has fallen short of what it once was and has the potential to be. In other words, we have become dwarfs of ourselves.

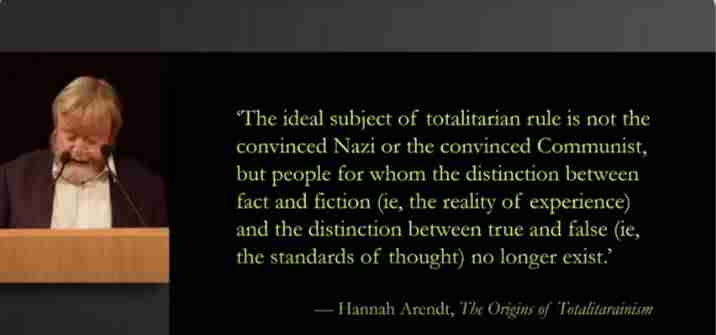

Hannah Arendt on Truth

Now, as well as the people I’ve mentioned, there is also Hannah Arendt on truth, a person with cigarette. But in this case, no beer. None I can detect. I don’t know how she got in, actually.

As far as I’m concerned, Hannah Arendt is almost a saint. Her work is so important now, there’s almost nobody that, if you haven’t read them, I would more urge you to read. And although her great works were published in the 50s and 60s and some of them even earlier, they are so prescient of where we are now.

And they’re not prescient because she could imagine something happening, because she’d seen it happen. She’d seen totalitarianism. She was at a little distance from it, but she was able all the more readily to see how it had happened.

So what she says is, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction, i.e., the reality of experience, and the distinction between true and false, i.e., the standards of thought, no longer exist.” That should make us sit up, I think.

The Decline of Political Discourse

The level of political debate these days is lamentable, and I’ve seen it plummet during my lifetime, both in Britain and in America.

If you look at some of the politicians, the caliber of them and the way in which they were able to discuss among themselves in a reasonably harmonious way is so much of a wake-up call when we look at the caliber of politicians we have now and the kind of easy mudslinging that seems to be substituting for serious thought about the predicament we’re in. And there’s also an unfortunate tendency to talk down to the population, which I blame a certain caste of middling intellect, middling politics, middling whatever. People who have taken over the big institutions and their mediocrity dictates everything for us.

It’s common that whenever people persuade, finally, Channel 4 to put on a marvelously interesting documentary or film, everybody says, why can’t we have more of this? But when the same filmmakers, because I’m talking about this, because I know this has happened in my experience, go to them and say, here’s another one. “Oh, no, it’s too difficult. They won’t get it.”

So we’re all being dumbed down all the time. And the trouble is, when you dumb people down like that, they behave as though they’re dumbed down because they actually become dumbed down. And the idea of people being held to high standards is now something that is considered undemocratic.

But without it, a civilization simply will quickly collapse. And those standards are being not met all around me every day. The idea of a democracy is not that we should all be equally crass in our taste and throw away anything that requires dedication and talent, reward the lazy and dull, or seek amusement in the basest of the most trivial distractions.

The Distraction of Society

But what we’re being offered is a sinister-looking pact. I don’t have some sort of paranoid theory. And I’m going to talk about where all this comes from.

But there is a sense in which we’re being offered metaphysical or metaphorical opiates, Huxley’s Soma, to keep the people distracted from the real issues and, above all, keep them from having a life. Because then they might act spontaneously. They might even learn to love one another.

They might form cohesive opposition to the powers that be, even notice that they’re being ripped off and disempowered. And so the need to divide, to encourage resentment, grievance, discord, aggression, disgust, and contempt, division, where there should be tolerance and patient attempts at mutual understanding. Self-interest and greed are there in the place of pride, in the spirit of collaboration, that builds a functional society.

And all this is very typical. I’m not going to go into hemisphere theory at all, because I assume that, probably, if you’re here, you either have already read or will very shortly read something I’ve written that will make it clear. But this is all very in keeping with the left hemisphere, particularly the emotional time.

So the left hemisphere is not unemotional, as people used to say. It’s the locus primus of aggressive feelings. And its general attitude is disgust, contempt, and the fueling of me, me, me, and discord.

The Dangers of Passivity

DR. IAIN MCGILCHRIST: So it is a serious point, but I’ll just put it before you and pass on. We’re being made passive. So Hannah Arendt again, for even now, laboring is too lofty, too ambitious a word for what we’re doing or think we’re doing in the world we have come to live in.

The last stage of the laboring society, the society of job holders, demands of its members a sheer automatic functioning. The only active decision still required of the individual is to abandon his individuality, the still individually sensed pain and trouble of living, and acquiesce in a dazed, tranquilized, functional type of behavior. Ring any bells? It’s quite conceivable that the modern age which began with such an unprecedented and promising outburst of human activity may end in the deadliest, most sterile passivity that history has ever known.

So we must not be passive. Arendt warned, as you know, that loss of faith in the institutions is a precursor to totalitarianism. And I’m afraid I have lost faith in institutions I once felt pride in.

Our great universities that I was honored to be a member of, our health care system that I was honored to serve in, our police, our armed forces, our government, no longer command respect, no longer seem to know where they’re going or what they’re doing. And part of this is a loss of innocence. In other words, nobody thinks innocently anymore about things that have value in themselves.

In its place, there’s a shallow knowingness, a cynicism, which seems clever, but interestingly, psychological experiments show that people who are cynical are of lower IQ. So it’s not clever. Those who are intelligent don’t need to be cynical about things, but people who are protecting themselves because they don’t really understand adopt a cynical view.

And I think of those great lines of Yeats from The Second Coming: “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned.” In other words, there’s an instrumentalizing of everything, and it changes its nature in that process.

The Problem of AI

AI compounds the problem a thousandfold. AI-generated evidence may support whatever narrative the international conglomerates wish to propagate. I say the international conglomerates because although traditionally there has been a sort of opposition, perhaps, between the public sector and the private sector, I believe that they now embody exactly the same drives and work in a kind of combination which is very hard for us to resist.

They are working at supranational levels, at global levels, where they’re no longer accountable to a population that elected them and can carry on the fantasies that the World Economic Forum, as David was saying, proposes. So, at the same time, it may propagate a narrative and claim there is evidence, from the point of view, that suits those conglomerates. But it may also, of course, monitor and suppress any kind of thinking that doesn’t align with that narrative.

Above all, of course, AI has no conception of what I mean by innocence. It doesn’t really believe in anything, of course. It doesn’t think.

It can’t actually, in any way, help us humans, except by taking work that is tedious out of our hands. And even there, it is not succeeding, as I shall explain. We don’t want to be more machine-like. We need to be better humans. And none of that will help us become better humans.

Pathways to Truth

I’m not going to do a lot about epistemology. I wrote about it at great length in the second part of The Matter With Things. But effectively, I’m asking, where do we go to find truth? And I’ve suggested that there are four main pathways. They are science, reason, intuition, and imagination.

And, in short, I show that each of these has its value. Each of these has its limitations. But, ultimately, we’ve been obsessed with science and reason as the only way to achieve insights into the nature of reality.

And, indeed, certain people have become very famous, like Dan Kahneman, who even got a Nobel Prize for writing a book which decries intuition. His own work can be easily falsified. And, although intuition can deceive us, so can lines of reasoning.

So can science. In fact, one way of thinking of science is it’s the process of untruth towards truth. So, science is always provisional and in process.

Now, some people might think that I’m, therefore, attacking science and reason. Quite the opposite. I believe they’re terribly important. And I believe they are under attack now.

So, for example, in the humanities, when I was growing up, the process was started by Marxism, in which everything was diminished and compressed and chopped off on the Procrustean bed of a certain political doctrine. And then this was followed by deconstructionism, which basically said, there is no truth and whatever I want to say is fine.

This is utterly irresponsible. It was wrong. And it was taking the basis from under the really important fruits of human creativity.

So, I do think that truth is very important in the humanities. But truth is also very important in science. And I regret to say that Nature, the oldest and most prestigious science journal in the world, has recently adopted a line that if research reveals uncomfortable truths that don’t fit with whatever the approved politically correct narrative is, they won’t publish it.

Now, once that happens, where are we? Science is our lodestar. When we can’t trust the science, we can’t trust them to just tell us what they found, but instead to go, no, well, these are things that are unsafe for you to know. Then we’ve lost something very important.

And of these, I mean, when Reason too is being suborned, Marcuse argued that rationality was being transformed from a critical force into one of adjustment and compliance with the system of life created by modern industry. Those were his words.

The Right Hemisphere and Language

Now, the real world, precisely because it is a presence, it’s a living presence, not a representation. That’s the distinction between what the right hemisphere knows and the left hemisphere’s map. But the very presence of life, it cannot be represented in concepts and language without distorting its essence. We can write about things, we can argue about them, but we should always be aware that what we’re doing is grossly simplifying what experience has told us and cannot be fully articulated, has often to remain implicit because once it’s made explicit, it becomes something else.

I mean, this is obviously true about all the things that really matter to us. Love, poetry, music, architecture, art, ritual, myth, story, religion, all these things have truths that once they’re reduced to the language of the dishwasher manual, is betrayed. It no longer has the power that is in its essence.

So that is, it’s not a weakness of the right hemisphere that it doesn’t have language. It realizes that language was a kind of a virus that had got in and it sequestered it in the left hemisphere largely. The right hemisphere understands language, understands it actually better than the left hemisphere, but it doesn’t compose the sentences that make for, you know, scientific prose.

And both of these are okay, but it’s not a weakness in the right hemisphere that it has decided not to use language because it realizes that language will distort.

The Nature of Truth

So the left hemisphere misconception is that truth is simple, can be fully known, is single, black and white, all or nothing, and independent of context. But as Oscar Wilde said, “truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

Mistaking part of the truth for the whole is one of the problems. I’m trying to think of the exact quote, but Whitehead said, “all truths are partial truths. It’s treating them as the whole truth that plays the devil.”

And I often think of the insight of John Stuart Mill that where there have been arguments in philosophy, it has most often been not that people were wrong in what they asserted, but that they were wrong in what they denied. And if we could remember that, that there may be more than one truth about something and that both points of view or all points of view need to be heard, we might be less in the pickle we’re in. And actually that sentiment was voiced by Leibniz over a century earlier in one of his letters.

So it’s a point that has a good pedigree. And context changes everything. The context of a remark can completely reverse its meaning.

And context is what we don’t take into account when we think that there are things that are in themselves absolutely the truth. As again Whitehead said, the real question to ask is not is this true or not, but in which circumstances can it be said to be true and in which can it be said to be false. And often just because a move we’ve made in one direction works, it doesn’t follow that making more and more steps in that direction will make things better.

Often it makes them manifestly worse. Truths always come with their opposite truths, something that the great physicists of the last century understood, that obviously the everyday truths don’t carry with them a shadow of an untruth. Either I had milk in my coffee this morning or I didn’t.

But when it comes to the really big questions, the really big truths, every angel has its devil and every devil has its angel. So what is real is in process. It’s an encounter.

Everything that we experience and know is out of an encounter of what I have in me with what the world that I’m encountering gives to the meeting. And so truth is always happening. But it is not the case that it is made up, emphatically not.

You can’t just say anything and say, well, that’s my truth. I mean, that’s just a ridicule the whole idea of truth.

The Importance of Imagination

Now, here I want to just say something about the importance of imagination.

So we are obsessed, of course, with newness as novelty. But there’s another way of newness which is newness of further unpacking the truth that is there. And that requires imagination.

Imagination is the opposite of fantasy. Wordsworth and Coleridge wrote about this very persuasively. So fantasy is what takes you away from reality. But imagination is the only chance you have of entering into reality. If you don’t use your imagination, you remain remote from whatever it is that you are encountering.

So all is changing and making a new all the time. But not from nowhere. It’s not like we should uproot everything and just start again. It’s an unfolding, like the unfolding of a bud in a plant, like the movement of a stream.

Is what is new good or bad? Well, it depends on the goal, the nature, and the degree of the change. So that’s what I say. And this is also… Thank you.

And this is true of everything, including AI. It depends on why it’s being used, how it is experienced by the humans who interact with it, and the degree to which it is allowed to intervene or interfere. So truth, imagination, and creation go together.

All our experience is an act of creation. We are always creating the world, not just out of ourselves, but out of a stream that comes from the past, of which we are the product, and goes towards the future that we have a duty to preserve and hand on in reasonable order to those who come after us.

The Creative Cosmos

So the creative… I think this is the nature of the cosmos. One thing you can say about it is it’s always creating stuff. It is always unpacking something new. So we start with a very simple thing, and then it explodes, and all kinds of things come into existence.

And the one and the many are a very important dipole to bear in mind together. It’s not all one, and it’s not all many, but the many is not an opposition to the one. People go, “Man, all is one.” And I go, “Yeah, and all is many. So now what?” And the thing is that this business of the unfolding of what is implicit into the explicit is the cosmos discovering its own nature. It may be the divine ground of being, exploring what it has the capacity to make, and feeling it reflected in another.

So it’s like this. The unfolding bud doesn’t destroy the plant. It fulfills the plant. It’s unfolded now, but it’s not lost. This process is important. And of course, there’s David Bohm’s work on the implicit.

The Implicit Order, a famous book he wrote about the physics of the cosmos. And what is sometimes forgotten is that he believed that it not only was a matter of unfolding what was enfolded, but then further unfolding the new whole so that it could unfold again into something new. So there’s always this dance of coming together and separating.

Goethe said, “Dividing the united and uniting the divided is the whole work of nature.” My God, did that man know something. Imagination also helps us see things afresh.

So the famous lines from The Defense of Poetry by Shelley: “It purges from our inward sight the film of familiarity which obscures from us the wonder of our being. It compels us to feel that which we perceive and to imagine that which we know. It creates anew the universe after it has been annihilated in our minds by the recurrence of impressions blunted by reiteration.”

So imagination is the faculty whereby we nurture reality into being. It’s not the faculty whereby we fashion an already existing reality. It’s not sort of in a cupboard waiting to be discovered. It is actually coming into being in our process of contact with it. Imagination is inextricably bound up with reality in a way that its bedfellow fantasy is not.

Data vs. Understanding

Now, there’s a lot of confusion about what we can know. And this comes from the fact we live in a world of data, of enormous quantities of data. And this leads to many misunderstandings when we come to AI.

Quite clearly, there’s a difference between data, information, and any capacity for this to have any meaning. It only has meaning when a consciousness that’s able to put these things in a context can create knowledge or at any rate an explanation. So one up from data is an explanation.

But explanation is not to understand. You say, I don’t really understand music. I can explain to you how harmonics work, how composers write, how these things are brought into being when they’re played, but I can’t help you understand the music for that something else.

The Sovereignty of Truth (continued)

In other words, imagination and intuition is required. Above explanation, which is just unfolding something within a certain context, as long as I imagine that the world is a sequence of events that trigger one another, then I can explain how something comes into being. And that’s valuable.

But it’s restricted. There’s further knowledge. And knowledge is of two types, which in most languages other than English are distinguished by different verbs.

So for example, in French, there is a distinction between savoir, to know the facts, and connaître, to know from experience. And in German, the similar distinction between wissen and kennen. So for example, I know savoir that Paris is the capital of France.

But I know Paris, connaître, because I spent three years living there and had an embodied experience of it, which gave me a different kind of path to understanding. It’s a more royal road to understanding than its partner. And here there are requirements for intuition and imagination.

And when it comes to wisdom, a fortiori, we need intuition and imagination.

The Hemispheric Imbalance

Now in a left hemisphere dominant world, and those of you who know my work will know that I believe that there is a gross imbalance between what the right hemisphere could tell us. We’ve stopped listening to it.

And it knows far more and is more intelligent, literally, both emotionally and socially, yes, but also cognitively, in terms of IQ. It is more intelligent. It is far more in touch with reality than the left hemisphere.

The left hemisphere is good for purposes of grabbing and getting, and that is what it is specialized for. But it is not specialized for understanding. Now this left hemisphere dominated world rejects truth for four reasons.

The left hemisphere is just less veridical. In fact, it’s often frankly delusional. And it’s not just me saying that.

I can quote numbers of neuroscientists or neurologists to be more truthful, those who actually understand what goes on in the lab in terms of what happens with human beings. When people have a right hemisphere and they’re trying to construe reality just from the left hemisphere, they become deluded in the most striking way.

Secondly, the left hemisphere only has a map, which is a very diminished version of reality.

And of course, it’s not important for it to have all the other information. A map is not more useful for having more and more information on it. In fact, it becomes unusable at a certain point.

Its great strength is that it selects only a skeletal structure of reality. And thirdly, it prizes internal consistency over new evidence. So if it discovers something, oh God, that means I’ve probably been wrong about this.

It goes, no, no, no, that must be wrong. I’m going to find a way of fitting it into my picture. And fourth, its sole value is utility and power.

It’s the exertion of power over the world to control it. All is instrumentalized. And tools of power, governmental or technological, are self-selected to go to the very hands in which you don’t want power to reside, who most commonly seek control? Psychopaths.

Hierarchy of Values

But utility is not the only value. So at the bottom here, this is Scheler’s Pyramid of Values that those of you who know my work will have seen probably more than once. I think it’s terribly important.

He thought there was a hierarchy of values and at the bottom were the values of utility and power and pleasure, which is like, this is good for me. Above those are the Lebenswerte, which are the values of life. So they’re things like courage, magnanimity, generosity, forgiveness, greatness of mind, all these things that are very important in a society.

Above them were the Geistige Werte, and interestingly in German, which often makes distinctions we don’t, intellect and spirit come together in the word Geist. But these are basically the platonic virtues of beauty, goodness, and truth. And at the top of the pyramid is das Heilige, the holy.

Now, I’ve shown here and elaborated that in what I’ve written, that effectively the right hemisphere sees that the lower levels support the top, but the left hemisphere sees the top as merely an excuse for finding utility and power and so on down this. Only fools and suckers, espouse virtues that will cost them because they aid others in society. But who but a loser would do a thing like that?

So I’ve talked about the humanities and truth and all of that.

And I note en passant in the way the debates in the humanities now go, the emotional timbre of the left hemisphere, anger, disgust, narcissism. In our world, wrote Orwell in 1984, “There will be no emotions except fear, rage, triumph, and self-abasement. There will be no laughter except the laugh of triumph over a defeated enemy.”

The Importance of Humor

Last night, I was talking to someone who’s undoubtedly in the auditorium today. And he was saying, if you had to redesign a curriculum for doctors, what would it be? And I said, well, actually the first thing to do is to select the right people because there’s things that can’t be taught if you either get them or you don’t. And he said, sense of humor.

And I thought, absolutely spot on. Sense of humor is so important. And sense of humor is being censored and driven out of our lives.

And you know, I’m a great fan of, and a friend, I’m proud to call myself a friend, of John Cleese. And I think his humor is one of the reasons for living. And you know, he went to Sarajevo and he was greeted by somebody who said, you know, you saved my life.

And he said, how did I do that? Well, when we were under siege, my daughter was murdered. And we just didn’t know how to live, how to sleep, or anything. But in the basement of a multi-story car park, we set up a cinema and we invited everybody we knew in.

And we played largely Your Monty Python and Fawlty Towers and all these things. And they filled us with a sense that, okay, it’s worth living. I think that is such a wonderful story.

Education and Intolerance

So, no educated person, I think, should be unwilling to engage in civil, respectful discussion. To quote Soros Nietzschen again, “It’s a universal law. Intolerance is the first sign of an inadequate education.

All ill-educated people behave with arrogant impatience, whereas truly profound education breeds humility.” And I think the new religion of wokeness shows discord in place of love. Speaks of freedom, but is coercive in opinions that it will allow to hear expressed, is superior, self-regarding, mocking, and aims to ruin the lives of those who dare to disagree.

The goal is absolutely not tolerance for all, but intolerance. There is a frontal assault on any standards by which you can appeal to reason or truth. If my truth is as good as any other truth, there is ipso facto no truth.

And if there is no truth, we are utterly lost. Education, I had thought, was about enlarging, not narrowing the mind. As is well known, the Greek word for truth, aletheia, means an unconcealing.

So it’s not that truth is there, sitting on a table, and I take the necessary steps and I find truth. But truth is a matter of clearing away, as Michelangelo produces David. He didn’t put it together.

He just threw away stone for years, and at the end of it, there it was. What has since time immemorial been accepted is ipso facto inverted, and its opposite made obligatory. We’re not progressing in intellect.

We’re throwing away the hard won, and I mean hard won, through hardship, through battle, in many cases, the hard won knowledge, skill, and insight that could have helped us out of our folly. What does the crisis of mental illness and the sheer scale of unhappiness in our society tell us about our experiment in destroying a society?

And why do scientists value truth at all if they believe the universe is meaningless and pointless and simply lump and matter coinciding and hitting and bouncing and so on? Why worry about truth? Surely in that world, the only decent thing to do is to increase pleasure. And if lies will make people happier, why not follow them? But amazingly, these people know.

They think truth is very important. I think truth is very important. I think it’s absolutely important, in science and everywhere.

But why would somebody who had no belief in anything beyond the material think it’s important? Both humanities and science should be in pursuit of the evolution of the new and the vital, but this requires encouraging an organic growth, not a cutting off from our sources, but like chaining a plant. You can make it go many places, but you don’t do it by breaking the stem and sticking it on a wall. You chain it there.

Technology and Creativity

But the left hemisphere produces something that is the opposite of creativity. It produces sameness. And in two senses.

So one is that the manifold becomes the uniform. And the second is that it endlessly repeats itself. Now, this is interesting because a number of commentators have noticed that technology peaked in its value around 2015, 2016.

Up till that point, it has shown itself to be indeed very useful. But since then, it has mainly impeded progress, taken up more time, unnecessarily complicated what intuition can lead us towards, and has generally starved us of time and energy. So tech has become less helpful and is now slowing us down and getting in the way of creativity.

And interestingly, about the same time, the internet had been, up to that point, interested in what people seemed to like and giving them it. But now it refers at a different level to what the internet gathers we like. So there are algorithms that dictate it that are no longer in touch with what people really like.

So in a way, this is the beginning of many vicious circles. When you ask ChatGPT a question, it goes out and does a trolley dash around the internet and comes back with a vanilla milkshake, which is a kind of mishmash of received acceptable opinion. But of course, for us to be alive intellectually, we need to debate.

We need to have different points of view represented. Wikipedia is appalling in this. It treats anything that is not already mainstream science as, quote, pseudoscience.

So how is it going to get to be the science of the future, which it sometimes may well be? Most things that we believe now that science shows us at one time were not what science thought. Science has to evolve. And once AI becomes our source of knowledge on reality, let alone our path to understanding it, all variety of views, all freshness of thought is banished from the world.

This is because it’s programmed to favor consensus views. This is thought control on a whole different level from anything predicted by Orwell and Huxley. And the left hemisphere specializes in vicious circles.

I mean, this is true about the brain structure, and I haven’t got time to explain it, but effectively, the right hemisphere has much more broad-ranging connections across many areas. So it is constantly seeking different points of view from different parts of that hemisphere, whereas when you exercise thought in the left hemisphere, it narrows down concentrically to an area where it thinks the truth lies. But of course, it may not.

It might be like that man who was found looking for his keys under a street lamp. Where did you leave them? Oh, I lost them over there. Why are you not looking over there? Because there’s no light over there.

So that is the way we are now regressing, not progressing. And by the way, I just want to say that nothing I’m saying has anything to do with left or right in a political sense. I think those labels are completely mistaken, and I think there are left hemispheric people on the right and on the left, and right hemispheric people on the right and on the left.

Capitalism and Bureaucracy

What I’m talking about is something that embraces capitalism and bureaucracy. Both drain our vitality. Capitalism trivializes, disregards the preciousness of all it exploits and helps to destroy, thrives on aggressive competition and discontent, promotes atomism and unrest.

Meanwhile, bureaucracy wastes our creativity, our freedom, and our time, which is all we have. It is our life. And things that used to take five minutes because you could ring and speak to a person, now you waste a whole morning going round and round up to another platform.

And, you know, it’s extraordinary because, of course, we now cannot bypass this and we cannot get to real people. And if we do, they’re equipped with an algorithm, which means that they’re more or less working like… So impoverished society adopts these harmful policies such as DEI as though this were a substitute for virtue. And both think, the big businesses and the bureaucracies, that we cannot see through that as a ploy.

Both propagate the left hemisphere mentality in the world, which AI now hardens up. And at the same time that we’re minutely controlling the minds of people, we’re not actually controlling their actions where they are harmful. So the police no longer seem to be able or willing to prosecute people for violent behavior in the street, for shoplifting, for crime that is escalating, probably because they’re too busy back in the station going through people’s Twitter feed in order to find a non-crime thought crime incident.

And then recording it somewhere. Any society other than ours would have found this and a host of other fantasies now banded around as gospel truth unimaginably absurd. Which one is the blind one? All those wise people who live before us? Or we? Just in the last 15 years have suddenly become terribly wise.

I’m not sure. And I think AI is like putting machine guns in the hands of toddlers because in order to use it properly we need to have wisdom. And wisdom is plummeting at the same time that power is growing.

So is it a servant or a tyrant? Well it’s always presented as your servant. But I might point out that any harmful innovation you like to name was without exception presented as for your benefit. It’s the sinister and serious aspect of those silly letters that you get.

The Fairyland Spell of Modern Society

DR. IAIN MCGILCHRIST: In order to improve our service to you we’re going to stop doing all the things you wanted us to do. And here Hannah Arendt is interesting. So in her marvellous book On Violence which you should all be reading as well as The Human Condition she wrote: “It’s as though we’ve fallen under a fairyland spell.”

Remember this is, I don’t know, 80 years ago. “We’ve fallen under a fairyland spell which permits us to do the impossible on the condition that we lose the capacity of doing the possible. To achieve fantastically extraordinary feats on the condition of no longer being able to attend properly to our everyday needs.”

So yes, you can always point to some machine that does something quite unnecessary and is extravagant on energy and time but can simulate walking about a room and look like a person. But actually you can’t do simple things like pay your gas bill. So this is a colossal expense of time and resource.

Pavel Kolhut, a Czech thinker who corresponded with Gunter Grass, foresaw a world ruled over by an elite that derives its power from the councils of intellectual aides who actually believe that men in think tanks are thinkers and that computers can think. Quote: “The councils may turn out to be incredibly insidious and instead of pursuing human objectives they pursue completely abstract problems that have been transformed in an unforeseen manner in the artificial brain.”

Can it bring us leisure? Well again Hannah Arendt: “It is a society of labourers which is about to be liberated from the fetters of labour and this society no longer knows of those higher and more meaningful activities for the sake of which this freedom was won.”

“Within this society which is egalitarian because this is labour’s way of making men live together there is no class left, no aristocracy of either a political or spiritual nature from which a restoration of the other capacities of man could start anew.”

We need seedbeds of people. The term hierarchy is a little unfortunate but what she’s really saying is there is excellence, there was excellence, we need that excellence and we’re losing it.

The Parasitic Nature of Modern Systems

DR. IAIN MCGILCHRIST: We’re in the grip of an ideology yes, but it’s not even that we’re a force of some kind we know not what that is not political but perhaps a cerebral malaise of what kind? Are we knowingly and willingly attacking ourselves or does the drive come from somewhere else? Well I would say both.

In other words it’s rather like cancer or parasitosis. So bureaucracy is like a cancer that draws the resources that were destined for teachers, for doctors or whatever and builds a shiny big building, awards itself huge salaries and proliferates at the expense of the host organism which it is supposed to serve. And AI is a parasite – it has ripped off human creativity and all it can do is try to imitate it.

This is an incredible impoverishment which we’ve never been consulted about and it feeds back to us a very basic person. So the thing about cancer is it is ourselves, it’s not somebody else’s self. The thing about parasites is they get into our system and we are a host to I think it’s 36 trillion bacteria on many of which our life depends.

We need them, they’re commensal organisms. In other words literally they sit at the same table with us. But this is a parasite.

And it’s expressed in managerialism and it’s both external and internal. And this is entirely consistent with the idea of a drive that is frankly evil. I don’t flinch from that word because I have never bought the idea that evil is just an absence of good.

Evil, I have experienced it. I’ve been a psychiatrist, I’ve led a life. I have definitely experienced evil. It has a drive of its own which it is to diminish to say that it’s simply an absence of something. It is a presence. And it doesn’t mean it’s necessarily outside of us – it acts through us as good acts and can only act through us.

So the big corporations, institutions simulate diseases in this way. The right hemisphere explores but the left hemisphere merely exploits – in other words it is parasitic. And what’s more it only wants and only understands what it itself has made.

It’s not in tune with whatever else exists with what for reasons of brevity one might call nature. And evil is not just greed though and again it’s an irrational lust for power for its own sake. And according to Hannah Arendt a distinctive feature of radical evil is that it isn’t done for humanly understandable motives such as self-interest but merely to reinforce totalitarian control and the idea that everything is possible.

I hope, yes. This is a cartoon by George Grosz from Between the Wars. It says a lot in a very small image.

Life No Longer Lives

DR. IAIN MCGILCHRIST: The future man says Hannah Arendt “whom the scientists tell us they will produce in no more than a hundred years seems to be possessed by a rebellion against human existence that it has been given a free gift from nowhere secularly speaking which he wishes to exchange as it were for something he has made himself.”

And as a result we come to this prescient phrase from the Austrian novelist Ferdinand Kürnberger: “Life no longer lives.” When I read those words, even saying them now they send a chill down my spine, but who of us does not understand that vitality is draining away, that spontaneity is being taken away, that choice and freedom are being taken away, that the characteristics of life are being supplanted by mechanism.

The birth rate is falling. Physical sexual relations are now too dangerous so teenagers prefer to indulge in pornography and do themselves to the internet rather than dealing with people who may suddenly turn on them and ruin their career or sue them. Dance has become solipsistic. Art has become cynical.

And what has happened to the ability to do something just on the spur of the moment? The right hemisphere was the dominant feature of the great periods of human creativity in both art and science as I explored in The Master and His Hemisphere.

What does live is the lie. And it’s been pointed out that in the war between the real and the bogus, the bogus is now preferred. So on the internet if you go for an image of somebody it will give you one created by an AI before it will give you the photograph of the real person.

Psychopaths actually prefer to lie and do so needlessly not for benefit but just because they’re addicted to the power of a lie. And so do utilitarians those who cannot understand goodness.

Coming together then, AI and capitalism exploit us, are parasitic.

I gather there was a woman with 713,000 TikTok followers who generated 11 million views for her videos. And this is all to do with the money that is paid for advertising associated with these things. And she got paid $1.85. The CEO of Spotify which is purely parasitical is reportedly richer than any musician in history.

AI requires piracy on a vast scale sucking dry human creativity. If AI were, as we’re told, revolutionizing fields such as healthcare, life expectancy should be rising not falling as it is. Mental health should show progress rather than a catastrophic decline the like of which we have never seen before.

If AI were all it’s claimed to be wouldn’t we see human society thriving not becoming less stable and less benign with every passing day? Disempowerment has hit us with the confluence of three important forces: global conglomerates, the central state, and above all the international bodies and forces that are not accountable to any country where there are citizens. The nature of unaccountability is wonderfully explored in Dan Davis’ book The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions and How the World Lost Its Mind.

So my last reflection is from Hannah Arendt: “The greater the bureaucratization of public life the greater will be the attraction of violence. In a fully developed bureaucracy there’s nobody left with whom one can argue, to whom one can present grievances, on whom the pressures of power can be exerted. Bureaucracy is the form of government in which everybody is deprived of political freedom, of the power to act, for the rule by nobody is not no rule and where all are equally powerless we have a tyranny without a tyrant.”

No one is responsible anymore, but we must be responsible and in my second lecture I will talk about how we do that. Thank you very much.

Related Posts

- How to Teach Students to Write With AI, Not By It

- Why Simple PowerPoints Teach Better Than Flashy Ones

- Transcript: John Mearsheimer Addresses European Parliament on “Europe’s Bleak Future”

- How the AI Revolution Shapes Higher Education in an Uncertain World

- The Case For Making Art When The World Is On Fire: Amie McNee (Transcript)