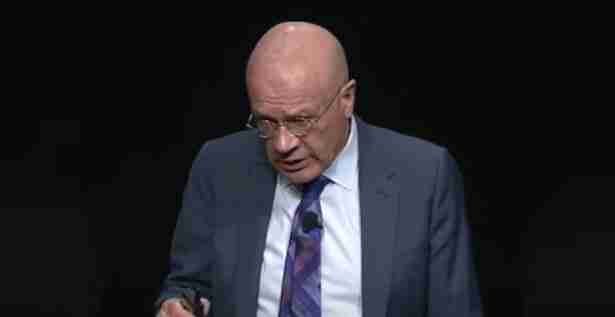

Read the full transcript of author Martin Jacques’ keynote address titled “What China Will Be Like As A Great Power” at the 32nd Annual Camden Conference in Camden, Maine, US on February 22, 2019.

Listen to the audio version here:

TRANSCRIPT:

MARTIN JACQUES: China, what’s it going to be like as a global power? Well, ten years ago, we probably wouldn’t have asked this question with a sense of imminence. We could see China rising dramatically, but we didn’t see it at that stage as a great power. Ten years later, the situation is very different.

First, there’s the decline of the United States, following or accentuated by the Western financial crisis. And secondly, there’s the rise of China, again, following the Western financial crisis, and the doubling in size of China, the Chinese economy, in the subsequent ten years, compared with the American economy growing by about 10% in that period.

And as a result of these changes, under Xi Jinping, there’s been a shift in Chinese foreign policy, which I think we’re all aware of, which is moving from the Deng Xiaoping’s idea of moving carefully, quietly, hiding your capability, hiding your leadership, to something which is much more outgoing and expansive, moving to the idea that China was not just a recipient of globalization, a player in globalization, but was also a maker and shaper of globalization. We’re in a new situation.

One of the difficulties, I think, that we’ve had in the West is we’ve always been on the back foot, we’ve always been a bit on the defensive, we’ve always been a bit behind the game when it came to China. We didn’t really believe in it beyond the point. We didn’t believe it was sustainable. And now, I think, we have to face the fact that this is a remarkable change that’s taking place, and we somehow have to be able to make sense of it, to understand it.

But the Achilles heel in the West has been that really, we don’t understand China.

Now frankly, this is no longer a sustainable position. It hasn’t been a sustainable position for a while, but it’s absolutely not sustainable any longer in the world, because we see not only the transformation of China, but so many developing countries which do not come from the same historical, political, cultural roots as the West. And we have to now try and understand, in this context, the difference that is China.

China is Not Like the West

China has never been like the West. It isn’t like the West, and it never will be like the West. I don’t mean that there aren’t connections, similarities, and so on, but there are some fundamental differences which are enduring differences. Now I want to make three points in this context.

The first is that China, we think of countries being essentially nation states, but China is not in any simple way a nation state. China, this was at the beginning of China, these are the crude maps I’ve got here, but 2,000 years ago, over 2,000 years ago, the beginning of China as a polity. The Han Dynasty, still over 2,000 years ago, you can already see is occupying a large part of the eastern part of China. It was only at the end of the 19th century, when China got into big, big trouble and became very divided and occupied in parts, that China finally conceded that it should be a nation state.

In other words, it adapted to the European, then European norms of the international system, and it began to call itself a nation state. So you know, that’s what, 120, 130 years ago, something like that? That’s a sliver of time when you consider a 2,000 odd year history of China. So to understand China, we’ve got to understand it, in my view, primarily not as a nation state, primarily as a civilisation state, that its inheritance is a civilisational inheritance.

Ideas about the relationship between the state and society, Confucian values, the role of the individual within Chinese society, traditions like Guanshi, a certain type of relationship networks in China, or even Chinese food for that matter, Chinese language, are civilisational inheritances of China, which way predate the period of it being a nation state. So China is a civilisation state and a nation state, and this marks it out, I think, in all sorts of ways, if we tease the different aspects of China properly, tease out the differences that China is about.

And there’s another example of this, you know, China of course is huge, those four provinces of China are bigger, have a bigger population between them than that of the United States. But the point I want to make here is that China, we think of China, we think of China as often, you know, a very centralised country, run from Beijing and so on, which isn’t true actually, it would be impossible to run a country the size of China, 1.4 billion people nearly, from Beijing.

China has many different customs, many different cultures, although its primary language is Mandarin, many different languages spoken, and so on. And so China learnt over a long historical period, pre-communist period, I mean I’m talking about the imperial period, that the only way that China could really operate and could hang together was if it was on the basis of a certain sort of respect for difference, if you like, or to put it another way, one civilisation, many systems.

And so for example, this lives on today, if you look at the handover of Hong Kong in 1997, Deng Xiaoping’s idea was “one country, two systems.” Very different way of thinking to that of a nation-state, drawn from the tradition of Chinese civilisation. A nation-state would never think like that, I mean German unification, it was one nation, one system. That’s our tradition in the West, that’s where it comes from our history, likewise the tradition of “one country, two systems” comes from a different civilisational tradition. So this is very fundamental.

The Relationship Between State and Society in China

Or take another crucial difference about China, which is the relationship between state and society. Now we, and I understand this, and I’ve been through this myself, we think of governance in countries as essentially about universal suffrage, multi-party system. And China doesn’t have that. And for that reason we’ve long believed in the West that the Chinese system as we know it today is unsustainable, is illegitimate.

But I don’t think if you look at the work that’s been done on Chinese governance, if you look at the Pew Global Attitude Surveys and so on, about the levels of satisfaction amongst the Chinese with Chinese governance, that’s a really sustainable position. It’s clear that the Chinese governing system, different though it, hugely different though it is from our own in the West, enjoys a great deal of support and legitimacy.

But what is the nature of this legitimacy? It can’t be the same as ours because we see it in terms of that democratic position that I’ve just described. Now in China the difference is, I think, crucially based on three factors.

First of all, the state is seen as the guardian and the embodiment of society. This is inconceivable that this will be the case in the United States, but in China it is the case. And it goes back a long time. We’re not just talking now about periods since 1949, we’re going back 2,000 years for this tradition.

Secondly, the idea of governance in China is drawn powerfully from the notion of the family. I mean, Confucius’ idea of the role of the emperor was that the emperor should model himself on a good father. It was a patriarchal tradition, of course, then. And so it was a family unit that acted as the microcosm, if you like, of China as a country.

Well, thirdly, the tradition of meritocracy, the importance of meritocracy, which goes at least back to the Tang Dynasty, 1,500, 1,600 years ago. So these are things which together the Chinese see governance in a different way to the way we see it. And it can be, as we’ve seen, extremely effective.

China’s Place and Role in the World

And the third and the final difference, which brings me to the subject of my talk tonight, is China’s place in the world, China’s role in the world. Now, you know, it’s strange to say that Europe and China shared a very important thing in their prime period. They both, in a sense, regarded themselves to be universal, that they were superior forms of being, if you like, to those that existed elsewhere. But the way in which they interpreted this proposition was very different.

Europe interpreted this proposition essentially as an evangelizing mission to transform the world, to take the message of civilization to those who were not civilized, through the colonial mission, through Christianity, through language, through the culture, and so on. And I suppose the prime, most extreme expression of this was the height of European colonialism prior to 1914.

Now China’s interpretation of universalism was entirely different. China did not see it in terms of externalizing itself. Because the Chinese idea of their universalism was, “we are the Middle Kingdom. We are the land under heaven. We are the highest form of civilization.” So why leave China? What’s the point of leaving China when, as it were, we are all that could be?

So the Chinese interpretation of universalism was essentially a stay-at-home universalism, whereas the European version was to go overseas, to go around the world. That’s why the United States is the United States, because it was a product of that evangelizing mission of European civilization and European colonialism.

Now these differences are very important to understanding today the difference between, I think, the Chinese way of seeing the world and China’s role in the world, and that of the West. The United States in particular, of course, is by far the most important Western country.

Now the characteristic forms of all countries that expand are firstly economic, that you cannot become a great power unless you have a powerful economy. Therefore, the major players globally, historically, in the modern period, Britain, then the United States and China, have all shared this characteristic in varying degrees. So that is an important commonality.

But beyond that, I think, I would say, looking back at the history of the West on the one hand and China on the other, here we have a marked difference, a marked disparity. Because military power and political power and political control have been extremely important in the Western tradition. I mean, maybe the highest form of this, as I said before, was colonialism. But it’s been extremely important in the way in which the Western tradition has related to the rest of the world.

Now China is rather different. China didn’t, I mean, do you know, in the 500 years from the mid-14th century to the mid-19th century, China only fought one major war with another country, which was Vietnam, which they got a bloody nose and eventually were defeated and had to retreat. There were only two major wars, actually, in that whole 500-year period between major nations or countries in Asia, compared with, say, 142 wars just between Britain and France. I say it’s true, in that same 500-year period.

So for the Chinese, actually, you know, the Chinese have this system called, it’s become called, at least in Western terms, the tribute system. And the tribute system lasted for probably about 3,000 years, the longest existing international system or partial international system in the world.

And this was essentially, it was not a military system. The Chinese did not, apart from that Vietnamese example, invade other countries. It did not, by and large, interfere in the politics of other countries. So there isn’t a strong tradition, or any real tradition beyond a point in China, of exercising military or political power.

What mattered to the Chinese was cultural power. If you were going to be a tribute state of China, then you had to recognise the role of the emperor, the superiority of the emperor, the land and the heaven, the Middle Kingdom and Confucian values. You were required to do that. And as long as you did that, you could more or less do anything, up to a point. But that was essentially the Chinese system.

So we have here a very interesting point of departure in comparing the Western tradition historically and the Chinese tradition. Strong emphasis on military and political power in the Western tradition, strong emphasis on cultural power in the Chinese tradition.

The economic power is shared, but it’s also, I think, got to be said, that in the future, Chinese economic power, because of demography, is likely to be much greater than anything we’ve historically seen. Much greater, relatively speaking, than compared with the United States, even in its prime at the end of the 40s and 1950s.

Okay, so this brings me, slipping through history, to the present. What are going to be, I can’t cover all this ground, obviously, because there’s a lot of things to say, but let’s say, if I’ve got time, the seven key characteristics or elements of China as a global power. Of course, they are, well, partly they’re rooted in reality, we can already say, partly I’m speculating and who knows whether I’ll be right or not.

China’s Economic Power

My first point is, indeed, about China’s economic power. And I think that, well, we have to recognize, and I think we do recognize, that China’s economic transformation has been remarkable, even now, but well, as of 2015, it already represented 15% of global GDP, and I think the figure now is something like 16 or 17% of global GDP, which is remarkable, given in 1980 China represented about 1% of global GDP.

And the prospects, well, who knows whether this will become true, but these are some figures from Huang Gong at Tsinghua University, and this is based on GDP measured in terms of primary purchasing power, not exchange rates, it would be different if it was exchange rates. But in 2030 or 2035, you know, these projections are always speculative, China would account for a third of global GDP, which, by the way, is what China accounted for in 1820.

So there is a tradition, if you go back far enough, of this, followed by India then, and of course, second here is India, at 90%, but the Chinese economy, bigger than the American and the EU economies together, and twice the size of the American economy. Now, you know, many a slip tricks cup and lip, these kind of projections, I think, broadly speaking will come true, but maybe significantly so, I mean, there’s lots of things that could happen in the meantime that could change that situation.

But I think that we would be, given recent history, we would be mistaken in not taking these kind of possibilities very, very seriously. And I think it immediately emerges here that, actually, China’s economic power is going to be, as I mentioned, disproportionate, disproportionate compared with anything we’ve ever witnessed in modern times previously, disproportionate even compared with that of the United States, and certainly with Britain.

I mean, did you know that Britain never accounted, even at its highest point, it accounted for about 8.5% of global GDP, and never larger than that, but was able to have an empire which controlled a fifth of the world and a fifth of the world’s population, but it never had that strong an economy.

China’s Relationship with the Developing World

So, my second point about China, China as a global power, is about its relationship with the developing world. Now, there is no doubt at all that the most important bilateral relationship to China is that with the United States, and it also regards its relationship, although in a rather different way, with the European Union to be very important. But strategically speaking, I don’t think that is an accurate way of seeing how China views its relationship and its priorities in terms of the world.

I think that China’s most important strategic priority in its thinking is its relationship with the developing world. Now, I think that a key part of the explanation for this is where China’s come from. China, of course, in 1978, when Deng Xiaoping’s reform started, was extremely poor, and was poorer than a lot of African countries in terms of per capita income, and so therefore it’s seen itself as having a certain affinity with the developing world, that it understands the problems of the developing world.

Furthermore, of course, there were other attractions of its relationship with the developing world. For example, China, like other East Asian countries, Japan, Korea, is very poor in natural resources, and China, to fuel its industrial transformation, needed large amounts of raw materials. So, the relationship with Africa, which actually dates back a long time, to the 1950s, was very important to China.

But I think, above all, it feels also that it understands developing countries. It understands what the problems of developing countries, and I think this is a fair proposition. China is obviously much closer to that situation, that experience, and that need, than the United States or European countries, which are much richer, and so the mind of the population in our countries, in the rich world, is very different, is in a different place to that of those in the developing world and in China.

So, China, I think, sees its future very much in terms of its relationship with the developing world. This explains why, for example, it’s developed such a strong relationship with African countries. Now, there have been a lot of criticisms of China’s relationship with the African countries, but I think that if you look at public opinion, for example, in Africa, according to Pew and so on, the majority attitude, 60-65% of Africans have what’s called a favourable attitude towards China.

And one of the things China’s done is, by becoming a serious source of demand for African raw materials from those countries that produce a lot, has boosted the prices, and one of the reasons why I think African growth rates over the last 10 years, probably the biggest single reason why African growth rates are now very strong in some countries, is because of this relationship with China.

Also, I mean, China, unlike the West, the Europe and America wasn’t really involved in this, but European countries, has been generous in terms of, and recognised the importance of providing infrastructure and so on. It’s made mistakes, it’s criticised, and so on. But I think that you can see from this, you know, the role that China has been playing. Unfortunately, the American relationship with Africa, the trade has been falling, but you can see that China’s been a very important player. And I think this is unlikely to continue.

And just bear in mind here, a very important point. Do you know that in the mid-1970s, two-thirds of global GDP was accounted for by the Western world, which is roughly 15%, it’s been declining, but let’s say 15, 16% of the global population. And only one-third by the global, by the developing world, where 85% of the world’s population lives.

Today, the figures are, this year, are 59% is now accounted for by the developing world. And I’ll get my figures right here, 39% by the developed world. And the projection for 2030 is that the developing world, called South here, will account for 67% of global GDP and only 33% by the rich world. So China’s relationship is a very populous developing country itself, but now an upper middle income country. You can see, thinking of the future, how important this is going to be to China as a great power.

The Belt and Road Initiative

Third point. Belt and Road. Now, of course, this is not, in a way, you know, in a way, I think, China sort of learnt a lot about dealing with the developing world, cut its teeth with Africa in the period of the last 20 years or so. And Belt and Road is, as you, I’m sure, are all aware, is a hugely ambitious project to transform the Eurasian landmass, where there are many, many very poor countries, although there are also rich countries at the end of the Eurasian landmass, is somewhere called Europe, which is certainly not poor.

But the idea, I think, is this. The Chinese thinking in relationship to Belt and Road is, look, we, how do we transform our country? We transform our country by economic growth based on very large scale, usually state investment, and especially directed at infrastructure. I mean, you know, China does have, for a developing country, an extraordinary infrastructure of expressways, of railways, and a larger high-speed rail network than the rest of the world put together.

China have really majored on infrastructure in a big way, and I think this has been so important to the development of China, because it’s created a connectivity across China, which has drawn the country together and allowed the market to develop in the kind of way that it has. And I think the Chinese thinking in relationship to Belt and Road is, if it worked for us, why can’t it work for the many countries of Central Asia, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and so on.

Well, that I think is essentially the Chinese thinking in relationship to Belt and Road, and bear in mind that about 65% of the world’s population lives in this landmass. Now how has it gone? Well, you know, they came out of the traps running hard, and a lot of money, a great deal of money has already been invested, and there’s been a lot of enthusiasm, hitherto, from not all the countries in the Eurasian landmass, but I think there’s 71 countries are lying along the route of, I should have put the, sorry, that helps us, doesn’t it?

It’s always good to have a map, I find. And you can see the green lines are the land routes, well, the green lines and the red lines are the land routes, and the blue is the maritime route, so Belt and Road, I know it’s crazy language, but believe it or not, I always get confused about this, the Belt is the land route, and the Road is the maritime route, can you imagine that? So I don’t know why they just didn’t stick to the name Silk Roads, because we all kind of know what that means, but there you go.

So a lot of enthusiasm from many countries for the project, because they can see the possibilities of how their circumstances could be transformed. The two key countries that have not signed up for it are Japan and India, and they were not represented at the big summit two years ago in Beijing, but many, many countries were at very high levels, often at the highest level of all.

Western Europe has been, well, it was represented, most governments, but not at the highest level, usually, and I think that gives you a sort of picture of what the support, what the attitude was. The United States’ attitude, as it was on the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, was to not get involved, not join in, and so on, and has recently been to develop an alternative approach. Personally, I think this is a mistake.

I think the United States should get involved, because if it’s not involved, then it’s not a player in terms of the rules, the regulations, the projects, and so on, and personally, I think the alternative program will just be too weak in terms of its funding. I mean, China’s throwing a lot of money at it, and I don’t think America’s in a position to do that at the moment or for the foreseeable future.

Now, it is also true, and must be emphasised, that China’s run into some serious problems in different countries with Belt and Road, notably Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Malaysia, some criticisms in Pakistan. So what is the problem here?

Well, the biggest criticism of China in this context is, the most recent criticism anyway, is that in extending loans to these countries, usually very good interest rates, around about 2%, these countries have taken on debt burdens, which will see them in big trouble. And I think that China has a problem in this context. Why?

Well, you know, this is a vast program, so some Chinese companies, some state-owned companies and so on, they rush into it, they want to do a deal, the Chinese banks are backing it, China Development Bank and so on, and they take on commitments which are excessive under the circumstances, where they need to go slowly rather than very quickly.

I think a lack of political awareness, political nous, I mean Malaysia, classic example, Malaysia historically has been quite close to China, Mahathir, I know, who I happen to know, is very pro-China, but he’s been very critical of China in this context. Why? Because the previous government of Najib undertook these big commitments, brought in, got lots of loans from China, and put the country in a lot of debt, and Najib was a particularly corrupt figure, and now Mahathir has cancelled, or not yet cancelled, but suspended some of the key projects like the East Rail route.

So I think that there’s a certain degree of sometimes greed, sometimes corruption, sometimes just, you know, rushing into things, lack of knowledge about the political circumstances of different countries, lack of awareness of the importance of civil society and civil society organisations and so on.

So I think that is very important. What’s going to happen? I think what’s going to happen is the Chinese will renegotiate all these agreements where they’re under a lot of pressure, and this will, I don’t think it will bring Belt and Road down, I don’t think the Chinese will let that happen, I don’t think they can let it happen, but it is a warning to them. But in the longer run, what do I think?

I think that Belt and Road basically is going to be successful. On what scale? I don’t know. Remember we’re talking about a very long-term project, I mean, I don’t think we’re talking about 10 years or 20 years, we’re talking about 50 years or more than that. This is a most extraordinary objective.

But what I think is going to happen is, you can see this map here is by Danny Kuo, who was at LSE, London School of Economics, and he tries to understand, try to work out, very complex econometrics, where the centre of the global economy is. And he estimated that in 1980, it was yellow spots just off the African coast, and he’s seen it moving and now he thinks it’s just above the Arabian Peninsula, that is now the centre of the global economy. And he predicts it’ll be, by 2050, on the Sino-Indian border.

And the transformation of the Eurasian landmass as a result of Belt and Road can only accelerate and underline that kind of development. That’s one point I would make. The second point I would make is that don’t underestimate the kind of transformation in governance that is likely to come from Belt and Road. Many countries, at the moment, there aren’t really strong regional organisations across large parts of the landmass.

And I think what we’re going to see is a transformation in the idea of the nation-state, new regional entities being created, in other words, a revolution in governance across the region in ways that, at the moment, I can’t predict exactly what they’ll be, but I think there would be inevitable consequence of this process.

And the other thing I think is almost inevitable, especially if Europe and the United States are not particularly involved in it, and that is increasing importance of the Chinese renminbi as a currency in these areas, increasing importance of Chinese ideas about how these kinds of projects should be organised, their legal basis and so on. Two courts are being established, one in Xi’an and one in Shenzhen, to hear commercial disputes in Belt and Road projects, which is an illustration of this point. So that is Belt and Road and a very important project.

China’s Military Expenditure and Political Meddling

Now, this brings me to just a couple of points that I want to make, which is, very quickly, I don’t think, I think in terms of US-China relations, we shouldn’t exaggerate the importance of Chinese military expenditure. China is not Russia. The Soviet Union was believed in military competition and the arms race, and you can see even today, when the country is much weaker and much poorer, it still places a disproportionate emphasis on military expenditure. I don’t think China is like that.

Takes me back to the earlier point about history and China not essentially regarding military power with the same priority as is true in the West and certainly in the case of Russia. And the other point I want to make, before just finally making some points about US-China relations, and that is, China is also not going to be a political meddler. Why? Because China thinks it’s different, it’s unique, it’s not a model for others, and it has an agnostic attitude, actually, a relatively agnostic attitude towards political systems wherever they are.

US-China Relations

This brings me to my final point about the United States and China. We are now, as we all can see very clearly, in new waters, in new territory, as far as the relationship between the United States and China is concerned. The era that started with Nixon now, in 1972, has come to an end. Why has it come to an end?

Because the United States has shifted its position. Not just Trump, I think, but more widely across American society. Why has it shifted its position? Because I think for a long time, America saw China not as a rival beyond a point to the United States. It was a very, very unequal relationship, but we can all see that that balance has changed, and now there’s a feeling in America that China, in some ways, is a threat, or certainly a challenge to the United States.

I would say, first, that it is impossible for the United States to stop the rise of China, unless we’re talking about nuclear war, but then we’re all dead anyway. The rise of China is one of these great, quite unusual, historical moments of a fundamental transformation taking place in the world. The rise of Europe and the decline of China in the 17th and 18th century was also one of these great historical trends, historical periods. The United States cannot stop the rise of China. This is impossible. So it has to try and find a way of relating to China in this new context.

Second point I want to make. The problem of the relationship between, the competitive relationship between China and the United States is not fundamentally about trade. It’s fundamentally about innovation. Now there has been a very strong view in the West that China was not capable of serious innovation, that China was good at copying, good at imitating, but when it came to creative change, radical change, China would not be able to succeed. Now I think this was a profound misconception.

You see, ever since 1978 it’s true that in the early decades China was by and large taking existing technologies and applying them to the new circumstances in China, but even that kind of approach is not simply copying. It involves a process of incremental innovation, not radical innovation, but it’s nonetheless innovation. And I think across Chinese society, when it was growing at 10% a year or now 7% a year, this led to an enormous build-up of innovative capacity, of innovative thinking across Chinese society.

This was not just, you know, this has been going on for a long time, and now China’s reached the point where it is capable of competing in areas which you and I, certainly I didn’t expect China to emerge as a serious player in the world. I mean, you know, the United States has had a monopoly, basically, of a lot of technologies, particularly those coming from Silicon Valley. And yet within a very short space of time, maybe 10 years, less than 10 years, firms like Tencent and Alibaba have emerged as, you know, on a par with the top American technology firms. So the monopoly has to be included in this category. So China is, China’s rise, economic rise, is going to be a formidable challenge to the United States.

And the only way that I think America, I think it’s a mistake for America to react in a protectionist way to this. I mean, I’m not saying don’t do any protection whatsoever under any circumstances, but in general, the danger of protectionism is that you withdraw as a defensive response, when in fact, basically, for example, it’s very, very important that American firms are competing in China because China is becoming such a competitive, ruthlessly competitive and dynamic economy. So you have to be part of it to learn from it, because learning is going to be very important in relationship to how we in the West respond to the rise of China.

My last point, and I’ll finish with this, is the key question, I think, for us in the West is, and particularly for the United States, is to find a way of relating to China based on a different assumption. The assumption can no longer be we are number one in the world, and we will just defend what we have achieved, because the situation has changed. China is a serious competitor in many fields now to the United States.

So we have to do what my country has not been good at, my country being Britain, which is learning to live in a world which is not the same as we’ve lived in for a long time. And we’ve found it very difficult in my country, the Brexit debate is a fantastically good illustration of this, we’ve found it very difficult to move on.

And I think the great challenge for the United States will be how to live in a world where China is a peer, a peer competitor. What are the forms of cooperation, and what are the forms of rivalry? This is the question raised in Thucydides’ Trap by Graham Allison, you know, how does the United States deal with this challenge, other than putting up the barriers and becoming more military, for example, in response. This isn’t going to work, this cannot be the future, so this is the great challenge that faces the West, but particularly the United States, in response to the rise of China as a great power.

Thank you very much. Thank you.

[Moderator]: All right, Martin, thank you very much for that very thought-provoking opening setting of the table with your thoughts. I want to start out by interrogating one premise of your argument, and that’s not the part where you say that China is on the rise, that’s fine, I think most people would agree with you that China is indeed on the rise and has been for more than 20 years now.

But I would like to interrogate the part where you presume that the West is in decline. Life is still pretty good for many people throughout Europe and for a large proportion of the population in the U.S., and life is still quite, in fact, very difficult, I would say. As a reporter, we get to see these things.

For most people in China, notwithstanding the many, many, many millions of people who’ve been risen out of, who’ve been lifted out of poverty in China. The Communist Party continues to tighten the screws, and a lot of that bureaucracy and other things endangers China’s economic rise. And China has actually, I think some would say surprisingly, proved to be quite vulnerable to U.S. pressure on trade, whatever one might think of President Trump and his rhetoric and methods and him as the messenger.

So how do you actually back up that argument that the West is in an inexorable decline compared to China?

[Martin Jacques]: Well, it’s not, it depends on how you define decline, obviously. I define decline as not absolute decline, which is quite unusual. It does happen to countries, but it’s very unusual. But decline as relative decline.

That is, for example, what proportion of global GDP does the United States account for?

[Moderator]: Purchasing power parity, of course, though, as you say. Could be either. In the graph that you showed, though, where PPP.

[Martin Jacques]: PPP. But it’s true of exchange rates. It’s just that exchange rates is slower than, but again, if you do the graphs, they’re more or less parallel to each other.

So now, in terms of relative decline, I mean, the United States, for example, its highest ever proportion was, not surprisingly, during the Second World War. But even in the 1950s, American GDP, proportion of global GDP was just under 29%, something like that. And now it’s well below 20%. Now, that is a very significant decline.

It doesn’t mean that American living standards are falling, because by and large, for most people, but not all people, as we’ve found from the politics of the last few years, but basically, you know, American life has got better. Meanwhile, China’s relative, as I explained, relative proportion of global GDP has been rising very quickly.

So that’s what I mean. If you take Europe, it’s exactly the same position in relation to Europe. In fact, European decline has been more accentuated than American decline. And you know, there are other problems to worry about for the West. I mean, growth rates are very low.

I mean, you asked me this question 10 years after the global financial crisis, you know, and the impact on the West was, you know, was very bad.

[Moderator]: Even so far as to have hit Beijing as well, growth rates in China are also considerably lower than they were 20 years ago, 15 years ago, when you and I were both living in China. So give us the flip side of some of what you’ve explained to us in the keynote. What do you see as some of the major barriers and obstacles that China is likely to face in its rise?

[Martin Jacques]: Well, multitudinous. I mean, you know, if I’m giving this talk in China, especially five or six years ago, and the Chinese reaction was, oh, you know, we’ve got, you know, you’re exaggerating where we’ve got to, you’re underestimating the problem. So that, and it is true that if you live in a developing country, then, and China is still a developing country, then you’ve got many different problems.

You know, the economy is imbalanced, it’s, it has serious funding problems, all sorts of difficulties the economy has. What do I think the biggest problems are? I think the debt problem is a serious problem. This is, this is internal debt, it doesn’t have external debts, but it has internal debts and the internal debts are to, well, to banks, basically.

Excessive lending on the part of, particularly state-owned companies, not individuals, it’s, and also by local governments and provincial governments, especially local municipal governments. That’s one area. Secondly, I think that the growth of inequality in China is an underestimated problem, in my view. And the divide between rural and urban, and interior, coastal.

[Martin Jacques]: Well, yeah, I mean, this is part of the problem of a developing country, because what, the way, Deng Xiaoping’s strategy was a sort of spatial strategy, in a way, which was let, develop the south, the coastal regions, which is, you know, Guangdong, near Hong Kong, Guangdong province, Fujian province, and then up east, eastern coast, Shanghai, and so on. So their living standards are much, and their growth rates, but they’re not, no longer their growth rates, but their living standards are much higher than, for example, central China, so central China being, for example, Sichuan province, Chongqing, and so on, and much greater than western, western region of China.

Now, probably the consequences of that kind of inequality, providing it doesn’t persist indefinitely, because then it would affect the unity of the country, in my view, are not so serious. When it, because people don’t, people, someone living in Chongqing or Chengdu, don’t know, they don’t measure themselves against someone living in Shanghai, because it’s, like, so far away.

But when that inequality becomes, for example, inequality in Shanghai or Beijing, then, and it, you can see it, you can see it, it’s very vivid, then that can become a serious problem. And add to the mix the migrant workers, who’d be extremely important for China’s transformation. I mean, they’ve done, let’s face it, in labor terms, a lot of the heavy lifting of it.

And they still are not, they still can’t, you know, if they’re living in Shanghai, they still can’t get access to Shanghai education, hospitals, and so on. So they, then, you know, they have, because their, their, their household rights are from their hometown, and so on. And there have been, they’ve been talking about, as you know, reforming the hukou system, this registration system, but they haven’t got very far with it.

So I think those, those kind of, I mean, you know, you could, you could add, one of the good things about the Chinese is that when they face a serious problem, they do do something about it. So corruption, for example, corruption was a really serious problem in China. And they did, and I think that they’ve had, they’ve made a singular dent on this problem. Inequality, I don’t think they’ve really done very much at all on it.

[Moderator]: Well, I’m looking forward to tomorrow. Our first speaker is an expert on the Chinese bureaucracy, and I’m sure we’re going to press her on how much of the corruption push is corruption versus elite Chinese bureaucratic politics, because we could have a whole conversation about that. Also, the economists who are going to be joining us throughout the weekend can tell us about the Gini coefficient, and all the relative inequality, so we’ll hear a lot more about it.

All right. Let’s start out with some of our questions here in the audience. I saw this gentleman here raised his hand, someone’s going to be bringing a microphone right to you, sir.

[Audience Member 1]: Jim Matlack, Rockport. You gave a spectacular overview, thank you. But given the long civilization tradition as you described it, with the dominance of a paternal model, Confucian model, how would you describe the role and status of women in this modernizing China? Do they have, or can they ever reach, parity?

[Martin Jacques]: Thank you for that question, Martin. Mao, who said, women are holding up half the sky.

[Audience Member 1]: Yeah, well, that’s tough. It wasn’t very true then.

[Martin Jacques]: Actually, I think that, of course, if you look at many professions and so on in China, they’re very unequal, very gender, gender equality is very powerful. But, if you look, but I think there is a, I mean, there’s going to be, I think, a lot of conflict, gender conflict in China in relationship to this, which has already begun to express itself over the last five years, in various developments.

But I also, I mean, I think it depends on the professions. I mean, if you go now, in journalism, for example, there’s a very large number of women journalists. And, in fact, I mean, I don’t know the statistics for it, but this is based on my own, you know, my own circumstantial evidence. There’s been a big change.

And if you look at the composition of students, for example, I mean, I teach at, in China, Tsinghua Fudan University and so on. And I don’t know what the exact gender breakdown is, but there’s, you know, there’s a formidable proportion of women amongst them. So I think that there is change. But if you go to the party, if you look at the, you know, if you look at the picture of the Congress, you know, it’s almost male-only.

[Moderator]: Yes. And if you would like to know more about that, I would recommend you to read a new book that’s just come out by Leta Hong Fincher, who’s a journalist turned academic who has her degree from Tsinghua University. It’s called Betraying Big Brother. And it’s about feminism in China today. The book just came out a couple months ago. And it’s all about these last, say, three to five years of this rise of a feminist movement in China. So we get a lot of information from that.

We have another question right here.

[Audience Member 2]: Thank you. Don’t forget to identify yourself.

[Moderator]: Sorry.

[Audience Member 2]: Tom Remington from Cambridge, Massachusetts. You’ve argued that we shouldn’t regard China through Western eyes, that Western models of development don’t apply very well. If you accept the premise that Marxism and Marxism-Leninism are a Western import, what do you think is the future of communism, the ideology, the Communist Party, especially given that Xi Jinping is intensifying China’s commitment to communist ideology?

[Moderator]: Oh, great. We got a double political science question there. The unacknowledged Western import.

[Martin Jacques]: Well, you’re right. Clearly Mao and the Chinese Communist Party, you know, was founded on the basis of the Marxist tradition at the same time as most Communist Parties were founded. I think the Chinese Communist Party was founded in 1921.

But I think that one of the great successes of Mao was his ability to indigenize Marxism in a way that the Russian, the Soviet Communist Party failed to do. And I mean, and one of the consequences of this was growing friction, which we should not forget, between the Chinese Communist Party and Stalin and the Soviet Communist Party later on as well, leading to the breach at the end of the 1950s between them.

So, for example, the traditional Marxist position was that the working class is the leader of the socialist revolution, is the vanguard class and all that kind of stuff. Now, Mao’s position was the opposite to that. Mao’s position was that the peasantry in China would be the mainstay of the revolution. And of course that is exactly what happened, which is the opposite of what happened in the Soviet Union.

And one of the reasons why the Soviet, the Russian Communist Party, from immediately after the revolution was in big trouble was because it represented such a minority of the population, so it was very dependent on authoritarianism. Now, the Chinese Communist Party, I’m not saying it wasn’t authoritarian, but because it had a mass basis in the countryside, it enjoyed much greater support than happened in Russia.

And I think one of the reasons, you know, if you’re, how does a, you know, is a party, whatever the party is, whether it’s communist or, you know, your party or whatever, is it able to change? Is it able to move with the times? This is the great question, I think, facing political parties. And the Chinese Communist Party, you know, we’ve got to be objective about this, has clearly changed enormously, hugely. It’s abandoned a lot of its old ideological positions, but not everything.

So I think that the success of Mao was, you know, originally, was this ability to give the Chinese Communist Party Chinese roots.

[Moderator]: Well, socialism with Chinese characteristics was the phrase, of course. But if we’re going to have a conversation about the peasantry, well, then we might have to bring up the whole Cultural Revolution Great Leap Forward. That could take us down a whole other path.

[Martin Jacques]: That’s another few questions.

[Moderator]: That’s another few questions. I got a signal that we have a question from one of our remote locations. The question is from George West in Newbury, New Hampshire, who says, who attends Dartmouth, it looks like, will the success of China force a change in our democratic system? And what are the chances of this happening?

[Martin Jacques]: Well, I think, you know, this is a very important question. Nice and brief, but a big question. Which is, to what extent is what’s happening in the West now a consequence of the rise of China? It’s not a stupid question.

You see, you know, we’ve had the financial crisis. We’ve had the impact that that had economically, which was dire, the worst hit since the 1930s. And then we’ve had the political consequences of those economic consequences. And the political consequences have been a very big challenge to the governing classes right across the West, including here.

And a serious decline in support, certainly in Europe, for all the major parties, social democrat and right-wing, conservative parties. And a loss, a growing loss of faith of people, or a shaking of faith of people in the democratic system. Why?

Now, I do think that it’s not the example of China, because China isn’t, I don’t think people in the West see China as an example, and I don’t think they’ll learn certain things from China, but we’re never going to go down that path politically, because our traditions are completely different.

But the impact of the relative decline, the relative decline of the West, you know, you can feel this, the angst in the countries. I mean, the decline, for example, take European leaders, you know, or leaders in my own country, are diminished figures now. They’re seriously diminished figures. People do not respect them in the way that they used to. Why not? Because they don’t have command of the societies, authority in the societies that they used to have.

[Moderator]: But when you use the word command and authority, I hope you’re not suggesting that authoritarianism is a preferential, is a preferable system.

[Martin Jacques]: No, I’m not making any value judgments like that. I’m just saying, look, the question is to understand what the consequences might be. So in that sense, we need to be good analysts and observers. We don’t just, you know, fatal politics is just to, you know, only notice the things you like and ignore the things you don’t like. Then you’re in big trouble.

[Moderator]: And we’d have to put some big blinders on all over the world for the last several years. I think we have time for one last question up here in the balcony. Go ahead.

[Audience Member 3]: Could you stand up, please, sir?

[Moderator]: If I try to stand, I’ll probably fall down.

[Audience Member 3]: Oh, please don’t. No!

[Audience Member 3]: Sarge Cheever, Wellesley, Massachusetts. Sir, could you comment on China’s treatment of its minorities, which seems to range from historical toleration to enforced conformity?

[Moderator]: Are you specifically referring to the Uyghurs?

[Audience Member 3]: Uyghurs and Tibetans.

[Martin Jacques]: And detention camps in the West and Tibetans. I think that this is a very good question. I mean, I think it’s a very complicated question, actually. The reason it’s complicated, in one sense, I think, to me, it’s simple, and in one sense, it’s very complicated.

The complicated part of the question is, look, China is an extremely diverse country. Extremely diverse. Many, many different ethnic and racial minorities. But the most extraordinary feature of China is the way in which, over a very, very long historical period, the great majority, well over 90% of the population, by general agreement, have come to regard themselves as Han.

So, the Han is, you know, of course, ultimately, race, ethnicity, is a cultural question, not a physical question. Now, that is, and they embrace many, many different people. So, many minorities now regard themselves to be Han. And that’s not through repression. That is through the process of, you know, cynicization, if you like, over a very, very long historical period.

And I think Confucian, you know, the Confucian tradition was, had two sides to it. One was very open to difference and minorities. And that was when, essentially, they were confident. And at other times, very defensive and exclusionary, which was when they were on the back foot.

So, I think this, so, in many ways, I think China is, I’d say, has ethnically been a very successful country. But, I think, since 1949, there have been two, in my view, the biggest failure of the Chinese government has been in relationship to Xinjiang and Tibet, where this old defensive mentality, the old Confucian defensive mentality, has been, had the upper hand. And therefore, a lack of proper recognition of cultural rights, of religious rights, of the practice of those, has been very clear in Tibet and in Xinjiang.

Now, we should distinguish between the two, I think, as well. I mean, Tibet, I can’t, beyond a point, I can’t understand why the Chinese don’t pursue a different policy. Because Tibet is not a threat to China. It’s not. Xinjiang is a more difficult problem. Because Xinjiang is, is, you know, bordering on the other Central Asian republics. There is a serious Paris problem.

I was in Urumqi four years ago now, which is the capital of Xinjiang province. And it did remind me of my visits to Belfast and Londonderry during the Troubles. Because there were, you know, there were sort of semi-armed patrols and vehicles and so on all over. And so, it was clear that there was a serious Paris problem.

[Moderator]: Although one wonders whether that feeling was caused by the repression. The figure that you used of 90% of people feeling happy to be Sinified. I’m not sure where that figure comes from. I can certainly say traveling in Xinjiang and in Tibet and in minority areas in southern China, in Yunnan province, for example, those minorities don’t feel Han. And they feel sad that their culture is being suppressed. I’m thinking of Nashi culture. I mean, as a reporter, that’s the observation. So, I’m curious where the 90% figure came from. I don’t think it’s true in a province like Yunnan and so on. It’s repressed.

[Martin Jacques]: No, no, no, not repressed at all. What happens with industrialization and modernization is customs do get lost. You know, it’s not a question of political repression. It’s a question of the way in which commercialization, for example, of people’s lives and so on, leads to the loss of certain forms of customs and identities. And that has been true. That’s not just true of China. That’s happened rampantly across the West.

Now, you know, we may lose lots of languages and so on. We may very much regret this, but it’s not an easy thing to deal with. What I’m talking about, and I think the question is directed at this, is what about the clear political and social repression of people? And that is a different question. I think this is a big one.

I don’t go along with all the stuff that’s been said about what’s happening in Xinjiang. I don’t think that that is necessarily exactly what’s happened. But I do think the Chinese over quite a long period have got the treatment of the Uyghurs and the treatment of the Tibetans wrong.

[Moderator]: And is there a solution to that? Do you see a way, because I think the questioner seemed to be asking, why are they doing this? Is there a way that China can be convinced that these are not threats to them? These large minority populations. And I don’t know if in Urumqi, was that because I haven’t been to Urumqi in the last four years. I don’t know if that feeling of Londonderry, Belfast, which I didn’t know during the Troubles, I was never there. Was that because those people were politically repressed? Or what was the chicken and what was the egg? In Urumqi, what was the feeling there?

[Martin Jacques]: What happened in Northern Ireland was that the Catholic minority population basically had inferior circumstances to the majority Protestant population. It wasn’t just about religion, but shorthand, we’ll use the religious terms. And there was a long yearning, unsurprisingly, for unification with the Irish Republic. And hence the IRA and the Terrace Acts and so on. And eventually, of course, the solution was found in this. Well, there were. It’s not yet properly found, but there will be, in my view, a united Ireland. That will be what happens.

[Moderator]: I doubt we’re going to have a Senator Mitchell doing a Good Friday Accord for Xinjiang. But I don’t know. All right. I don’t know if we have time for one last question.

[Unseen Other]: No.

[Moderator]: I’m being told we do not. All right. Well, then let me thank everyone for being with us tonight and remind you that the Opera House doors here are going to open tomorrow morning at 745. In the morning, seating will be available at 815. The conference will begin promptly at 845. And just a nice note is, if you don’t know this, the two-hour parking rule in town does not apply on Saturdays or Sundays, so park to your heart’s delight. Please join me in thanking Martin for sharing all of his time with us. And we look forward to seeing you tomorrow.

Related Posts

- The Art of Reading Minds: Oz Pearlman (Transcript)

- Transcript: India’s NSA Ajit Doval’s Speech on Regime Changes

- Inside India’s Astonishing Solar Revolution: Kanika Chawla (Transcript)

- Is The AI Bubble Going To Burst? – Henrik Zeberg (Transcript)

- Why Writing Is the Ultimate Rehearsal for Public Speaking