Here is the full transcript of a conversation between Professor Klaus Larres and Professor Jeffrey D. Sachs on “Who Rules the New Global Order? Trump’s Tariffs, the Ukraine War & Russia, the Role of China, & the Future of the West”, originally recorded on 22 April 2025.

Listen to the audio version here:

Introduction to the Krasno Global Event Series

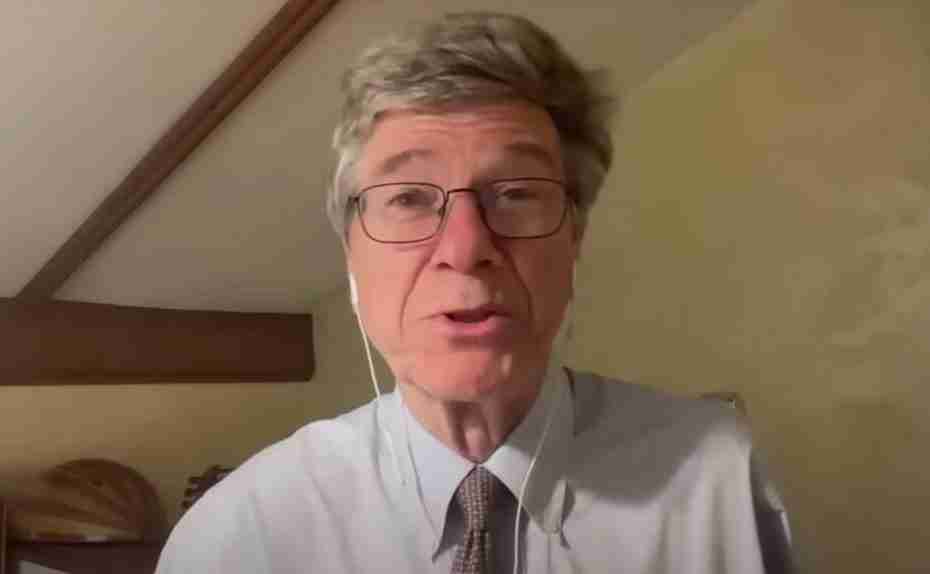

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: I would like to welcome you to the Krasno Global Event Series. It is great to see that so many of you have joined us by ZOOM today. I’m Klaus Larres and I’m the Rich Jam Krasno Distinguished professor of History and International affairs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I’ve run the Krasno Global event series since 2012, and as you can see, we are still going strong today. Our eminent guest is Professor Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University. However, today Professor Sachs joins us from Rome. Jeffrey Sachs, how are you doing today?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I’m doing very well and wonderful to be with you. Thank you for the invitation.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: You’re more than welcome. Thank you for joining us. Today we are talking about whether or not there is a new global order, whether one is emerging or has already emerged, and if so, who is in charge of that global order.

We are in the middle of a world in turmoil. US President Trump’s imposition of massive tariffs on many countries and above all, on China has greatly contributed to making the global chaos even worse. At the same time, climate change and environmental protection is going out of the window. And AI artificial intelligence seems to be taking over, at least according to some, the role of China in global affairs is becoming ever more important, not least as the Trump administration seems to be withdrawing from many parts of the globe, such as Africa, for example, and China is stepping in.

But the Ukraine war is still continuing.

I’m glad that Jeffrey Sachs is our honored guest today. There’s no one better to shed light on these and many other economic and geopolitical issues than Jeffrey Sachs. I know most of you are very familiar with Jeffrey’s work, but let me introduce him to you briefly.

Jeffrey Sachs is a world renowned economics professor, a best selling author, an innovative educator and a global leader in sustainable development. Jeffrey is widely recognized for addressing complex challenges in a creative way, including the escape from extreme poverty, the global battle against human induced climate change, international debt and financial crisis, national economic reforms and the control pandemics.

Jeffrey Sachs serves as the Director of the center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, where he holds the rank of University professor, the university’s highest academic rank. Sachs was Director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University from 2002 to 2016. He holds many other leading positions for the United Nations, the Vatican and universities and think tanks. He was also a Special Advisor to three UN Secretary Generals.

Jeffrey has also authored and edited numerous books, including three New York Times bestsellers. Jeffrey Sachs is a 2022 recipient of the Tang Prize in Sustainable Development and he was a co-recipient of the 2015 Blue Planet Prize, the leading global prize for environmental leadership. He was twice named among Times Magazine among the hundred most influential world leaders. And he has received 42 honorary doctorates, a very impressive number, I have to say. And he also got the Legion of Honor by decree of the President of the Republic of France and the Order of the Cross from the President of Estonia. Welcome Professor Sachs. It’s great to have you here at the Krasno Global Event series.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Thank you.

Trump’s Tariffs and Economic Policy

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: You’re more than welcome. Let me ask you straight away, as an economist, what do you make of the tariffs and economic policy of the Trump administration? Does that make an awful lot of sense or does it really create a lot of chaos?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Oh, my God. Chaos. That’s, that’s an easy one. I don’t believe it makes any sense at all. I don’t think the markets believe it makes any sense at all. We’ve lost trillions of dollars of market capitalization since President Trump began on this.

The stated purposes of the tariff, which are many stated purposes, are not going to be well served by the tariff. By stated purposes I mean the various explanations that have been given in justification. For example, to end the trade deficit or to rebuild the manufacturing sector, or to renegotiate the trading system or to punish China. These are variously given as explanations. I don’t think they stand up to scrutiny.

The international trade order, which is the global division of labor, we could say is there because trade is a mutually beneficial activity. As Adam Smith taught already in the wealth of nations in 1776. History has borne that out. The United States has benefited from the open trading system. The developing countries have benefited enormously from the open trading system.

Causing this kind of instability by breaking international trade relations will lower living standards in the United States. If this is maintained, it will create many problems for short term macroeconomic management by the Fed, which the Fed has pointed out and is the reason why President Trump has been attacking the Fed vociferously in recent days. They’re just doing their job, pointing out that these tariffs are going to make matters more complicated.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Because of that, do you see that the tariffs will actually have to be abandoned, that some compromise with the major trading partners in the world like the European Union and China will have to be achieved?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes, that’s already happened because just in the first days of the so called reciprocal tariffs, they were basically suspended because the financial markets began to react very dangerously. Not only the stock market, which fell worldwide, but the bond market, which started to fall in price and meaning to rise in interest rates, very significantly signified the fact that there was an aversion to US Denominated assets, including the treasury bills.

And that is what provoked a so called suspension of the tariffs. In other words, the markets worldwide gave this a very strong thumbs down. Trump backed down immediately. It said that his lead protectionist adviser, Peter Navarro, who somehow claims a PhD at Harvard, but he certainly didn’t take my class in international trade. He was away from the White House and supposedly other advisers rushed in to see President Trump and said, this has to be suspended. And so he suspended these tariffs.

There’s lots of talk about how we’re going to reach trade agreements with different parts of the world. I think all of it is to signify that the tariffs that were announced as these reciprocal tariffs are never going to really happen. But in the meantime, we’re in a real trade war with China. By real trade war, I mean China is not going to back down. Trump has not backed down. We basically have a break in this major trade relationship between the two countries.

Trump partly backed down immediately by saying these things. My iPhone, that’s going to come in tariff free because the consumers were starting to freak out and Apple was starting to freak out. You’re going to break your best consumer goods, Mr. President. And he said, no, no, no, no, we’ll give an exception for this one. We’ll give an exception for that one.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: So you don’t see that the whole tariff policy is a clever strategy to decouple from…

US-China Trade Relations

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Well, decoupling from China to my mind, is not a clever strategy at all because I regard US China trade as a win-win proposition. It became known as a win-lose proposition where China was winning and the United States was losing for strange reasons.

The US has made a lot of income gain nationally by having strong relations with China, by producing a lot of goods in China. Silicon Valley has invented a lot of products and those are then manufactured in China. And that’s a win-win. China has bought into a lot of intellectual property, so called service income of the United States. The United States has gotten a lot of consumer goods very inexpensively produced from China.

Of course, there are losers in trade relations as well. No doubt some companies that are in the direct line of imports from China have reduced their production and jobs have been lost in those sectors, but huge gains have been made in other sectors. And if we were a rational political system, we would say open trade is benefiting America enormously. Yes, there are some who are hurting and we should make sure that the winners help to compensate the losers.

This is what we teach by the second day of trade theory, that overall the economy gains, but winners do need to help compensate the losers so that the winning is across the board, or what we say, Pareto, improving rather than dividing society. But America is not very good at that. We don’t do redistribution. We leave losers to their fate. Losers in quotation marks. And Trump has appealed to them in both the 2016. Well, actually in all three election campaigns, and he won a lot of swing states in the industrial Midwest on the argument that you’re being hurt from the outside rather than being hurt by our domestic policy shortcomings.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: But listening to Trump, he argues that the trade deficit with China, for example, but also with other countries is of serious concern. The loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States needs to be addressed. And also some unfair trade practices by China and others about subsidies and unfair plagiarism and the pinching and stealing of international property and so on and so on. Does he have a point, or does he have no point whatsoever?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: He has a very funny idea. And the idea is that the trade deficit is a measure of cheating by other countries. Now, I’m a macroeconomist, and I teach what’s called an identity, in other words, a statistical relationship that that has to be, and that is that the trade deficit measures how much more we spend as a country compared with how much we spend, earn as a country.

And so if you go to the store and use your credit card and spend money you haven’t earned to buy something from the store, you run a trade deficit and you run up your credit card debt. In Trump’s world, you should be blaming that store for selling you things rather than saying, my God, maybe I should cut down on my indebtedness. I should watch my bank balance. I should not run up credit card debts. Instead, I should blame all the stores that I’m buying from. That’s Donald Trump’s vision of the world.

It’s frankly absurd to say that because the United States spends $1 trillion more per year than our GDP in essence, or our GNP, technically speaking, the American…

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Consumer is to be blamed. Is that what you say?

# Who Rules the New Global Order? Trump’s Tariffs, the Ukraine War & Russia, the Role of China, & the Future of the West

The U.S. Government as a National Credit Card

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Well, the one to be blamed, actually, is Washington. In the following way. Our government is like our national credit card. The government runs a huge deficit. It’s almost 7% of our GDP. It’s unbelievably large. The government’s running up debt. The government borrows on the markets and then transfers payments to Americans that are not coming from tax revenues. They’re coming from borrowing. And then Americans, both companies and households, spend.

So the American consumer is basically using that. They may not realize it, but the government’s their credit card. It’s our national credit card. We’ve run up 100% of our national income in debt. So if you, as an individual, run up debt equal to your one year’s income, that’s equivalent to what the United States has done. Is it manageable to pay that? Yes. But the interest costs are getting pretty steep. They’re about 3% of GDP just on interest now, and that will rise over time.

So what has happened is the government is used as a credit card. We spend more as a nation than we produce and earn. And as a result of that, we have this chronic trade deficit with the rest of the world, which Donald Trump then has inventively blamed the rest of the world. It’s incredible. It’s a little bit bizarre.

You can look up the following. If you do technically exactly the right calculations, you can add up how much we spend. That’s our consumption by the private economy plus the consumption by government, plus the investment by the private economy, plus the investment by government. And you subtract off the national income, which is the gross national product, and you will get exactly the current account deficit, which is the comprehensive measure of how much we spend abroad, minus how much we sell abroad in goods and services.

So it’s not even an analogy. It’s literally the definition of that comprehensive imbalance. But Trump has inventively said, oh, our current account imbalance, our spending income imbalance is the fault of everyone else.

Kind of bizarre. The markets don’t buy it. The rest of the world is befuddled. The economics community is scratching its head saying, this is pretty weird stuff, but we also have one person rule right now.

The Constitutional Question of Tariffs

And so I should just say something about that, which is that our trade system should be a matter of legislation as well as international negotiation. We actually have global treaty arrangements that established the WTO and that were negotiated with other governments about what the tariffs should be. We’ve ripped all of that up.

But we also have, under the US Constitution, Article 1, Section 8, the clear statement that taxation, including tariffs, which is the tax on imports, is the responsibility of Congress. If you go to Article 2, which is the executive branch, there is no responsibility at all of the executive branch for setting tariffs.

So already something is weird now, of course. What is weird, you can find out directly by going to whitehouse.gov and clicking on the executive orders about trade. And they all start out in the same way. It says, by the powers invested in me as President of the United States, and under the following emergency legislation, I declare an emergency. Trump is declaring a national emergency.

That’s not the kind of country I grew up in where a single person declared a national emergency. And what is the emergency? Well, it turns out it’s a trade deficit that we’ve run for 20 years. That’s not an emergency. That is a problem. But a problem that should be dealt with by the legislative branch, the Congress, and the President of the United States by law, not by emergency decree.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Yeah, I think you have a full point that Congress is not really standing up to its responsibilities and has abdicated responsibility to the executive. But there have been complaints about other trading partners for many years. Well before Trump, you know, I mentioned the subsidy culture of China, but also other countries, the stealing of intellectual properties and so on and so on. How do you address that? Because that seems to be quite valid.

The World Trade Organization and U.S. Hypocrisy

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Well, I don’t think it’s valid in a couple of senses. First, the United States abuses its trade policies all over the place, not just with Trump, but any time it wants. So there’s already, yes, abuses by the United States and by others. Simply pointing the finger at others misses the point.

And the point is that we created a system called the World Trade Organization. The United States actually led the creation of WTO. And we created a system where if countries are violating the terms of WTO, they can take measures against those other countries. And if the other countries say, no, no, I’m not violating the rules of WTO, there is an adjudication at the WTO. And if the adjudication rules for one country, another, that gives a right of response to those countries, for example, anti dumping duties or other measures.

And if the country on the losing side of that disagreement feels that the adjudication was mistaken, there’s an appellate court. Now, the United States has broken that process. Amazingly, it has blocked filling the appellate court of WTO. So it has said, we’re not going to have an international standard to judge. We’re going to be the judge and jury of anyone we want, rather than going to an international tribunal to decide these things, which is how properly this should be done. The United States points fingers at others. And this, to my mind, is seriously wrong.

I often say, by the way, in many different dimensions of foreign policy, I subscribe to Jesus’s foreign policy, if I may say so, because in the Gospels, Jesus says, why do you point to the moat in the other’s eye, when you have a beam in your own eye? And of course, what Jesus is preaching there is, don’t be hypocritical, clean up your own act.

And this, I believe, is a general principle for keeping the world safe, but it absolutely applies to trade policy as well. We’re very good at pointing out the moat in the other’s eyes, but when it comes to our own actions, we don’t even want to discuss it. And we certainly don’t want a judge to judge. We want to be the judge and jury. We don’t want the proper international procedures that we help to establish. We don’t want to be judged. And that is a sign, in my view, that we’re not abiding by the rules of the game.

The Ukraine War and Trump’s Approach

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thank you. Let’s move on to some other geopolitical issues beyond tariffs and economic policy. The Ukraine war is still continuing. The Trump administration is now putting pressure on both Russia and Ukraine to arrive at a ceasefire, but they have done that for quite a few weeks now without much success. So today we hear the new momentum seems to have developed. You’re quite critical of the Trump administration regarding its tariff and economic policy. Are you equally critical of Trump regarding its Ukraine policy?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No, I think on this one, Trump has it right. And he said it in a very Trumpian way. He said, this is Biden’s war. This isn’t my war. This is a loser. I’m getting out of it. I don’t want to be shackled with Biden’s war. Now you can unpack a lot.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: I thought it was Putin’s war.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No invade.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: I believe it was Vladimir Putin who invaded Ukraine.

The Historical Context of the Ukraine Conflict

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Right. Well, you know, I take a different view of this because I’ve watched this close up for 35 years. I was on the economic advisory team of President Mikhail Gorbachev. I was on the economic advisory team of President Boris Yeltsin, and I was on the economic advisory team of Ukraine’s President Leonid Kuchma.

So I worked with both countries very close up, and they were not in any way in conflict for a long time, I believe. It’s not a popular view, I admit, but I’ve been there and I’ve seen it. I believe the United States actually walked Ukraine and Russia into this war, not suddenly, not in 2022, but going back 30 years.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: A deliberate strategy or just happened.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: It was a kind of bluff. What the US wanted, and it was decided as early as 1994, was that the US would push NATO enlargement first to Central Europe, then to Eastern Europe, then into the former Soviet Union, right up against Russia’s borders in Ukraine and in Georgia, the South Caucasus country. And I watched that process close up.

I remember because I was a guest of Helmut Kohl in 1991. I was a guest of Hans Dietrich Genscher, the German foreign minister in 1991 in Berlin, because I was a lead advisor of the Polish government at the time. They promised to Gorbachev, and to Yeltsin NATO was not going to expand and it was not going to take advantage of Gorbachev’s unilateral end of the Soviet military alliance, the so called Warsaw Pact, which Gorbachev unilaterally ended, saying, the Cold War is over. We don’t need a military alliance aiming at the West.

And at that time, actually even the date February 7, 1990, James Baker the third and Hans Dietrich Genscher, the US Secretary of State and the German Foreign Minister, said to Gorbachev and publicly, NATO will not move one inch eastward. And Genscher was asked at the time, well, do you mean, Mr. Genscher, not to move into the new eastern part of Germany, which is going to unify with the Federal Republic of Germany, in other words, when the German Democratic Republic would unify, or do you mean more generally? He said, I mean more generally, we’re not going to move eastward.

And then as soon as the Soviet Union dissolved in December 1991, the American Security state said, come on, we have no enemies anymore. No one that can confront us. Rather than saying, we have no enemies, we should end NATO, they said, we have no enemies, we should expand NATO, we should make sure that Russia never returns, Soviet Union never returns, whatever that is.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: That is, of course, you’re right. This is the debate about promises given or not given.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Which is very, you know, people have very different attitudes about that and very different opinions. And the claims are still wishy washy because no written documents are available, but probably oral promises were made. And also it is a question whether NATO expansion really should have happened or should not have happened. But even if that all was wrong, and we say that was to be criticized, does that justify invading a country and killing civilians and bombing tower blocks and civilian infrastructure and people? Of course. So did Putin have perhaps grievances, but then went well beyond to try to satisfy these grievances?

The 2014 Ukrainian Crisis

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Well, there’s one more step of this that’s very important. Again, and by the way, on this question of NATO, I encourage people to go to George Washington University National Security Archives Online, and go to a website called “What Gorbachev Heard,” because it’s got dozens of documents that lay all this out very, very explicitly. It’s a wonderful program that George Washington University runs.

But what became awful was that in 2008, after NATO had expanded to Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic in 1999, and then to seven more countries in 2004, to the Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, to Bulgaria and Romania, and to Slovakia and Slovenia, so getting pretty far eastward in 2008 at the Bucharest NATO summit, George W. Bush Jr. insisted NATO will go to Ukraine and to Georgia, surrounding Russia in the Black Sea region. That was the idea that goes all the way back to Brzezinski in the mid-1990s.

The Russians said no. And our former CIA director William Burns was at that point the U.S. ambassador to Moscow. And he wrote a famous long cable back to Condoleezza Rice where he said, the entire Russian political class is dead set against NATO enlargement to Ukraine because they view it as a national security threat.

Now, the next step that’s really important is what happened February 22, 2014, because that was when the Ukrainian president was overthrown. Viktor Yanukovych, that was quite notable because Yanukovych favored neutrality. He was considered pro-Russian. He did not want to bring Ukraine into NATO. He was elected in 2009, came into office in 2010, and he favored neutrality.

He was overthrown on February 22, 2014. The Ukrainians that came to power called it the revolution of dignity. I call it a coup, a violent coup that the United States actively supported. And I happened to see some of it, sad to say, up close because the US funded a lot of the coup and the Russians knew it.

They actually intercepted a phone call between somebody who’s now my colleague actually at Columbia, Victoria Nuland. She was at the time the Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs. She made a call on an open phone to the US Ambassador, Jeffrey Piatt, and they talked about in end of January 2014, who would be the next government. And by the way, at that point, Biden was vice president, and he was the one that was going to come seal the deal. It’s all on the tape. It’s a shocking, shocking call.

So my view is many historians agree with me, others argue the point, but my view is the United States was part of an active regime change operation because they wanted to overthrow a president that opposed neutrality.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: This is very, very controversial, as you rightly say, you know, and some people would, of course, agree with you, some people would disagree with you. And also what you didn’t say was that the Ukrainian president wanted to conclude or went back from concluding an association agreement with the European Union.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: That’s correct.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: That caused the Ukrainian population to rise up, particularly in Kiev, and that caused at least a lot of the revolution at that time. Whether it was all financed and supported as much by the United States, I don’t know personally.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Can I just mention I agree with you completely. But just to tell you, one of the groups that funded this explained it to me thinking it was, I mean, with a lot of pride, by the way, in 2014. It horrified me, I have to say. But somebody explained to me how much was given to that group, that group, that group, that group. So I found it ugly. I have to just explain, even.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: If that is all correct and all true, does that justify an invasion of Ukraine, as we saw with the takeover of Crimea in 2014 and the beginning of the infiltration of Russian soldiers or little green men into the Donbass? And then, of course, the full scale invasion, February 2022. Can that be justified by what you just described to us, or should there not have been other ways and means to resolve Putin’s grievances? Because it was also clear that NATO wasn’t about to attack Russia either, was it?

Russia’s Perspective on Crimea and Ukraine

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Well, I think what Russia did with Crimea in March 2014 made perfect sense from Russia’s point of view. Because what the Russians thought, believed, and I think they were right, is now that this coup has occurred, NATO is going to grab Crimea, and Crimea is the home of Russia’s naval base, and it has been the home of Russia’s naval base since 1783. And Russia saw this as a game going on. And it was a game. The United States participated in this coup.

And the idea, in my opinion, but based on my observations, they were replaying the Crimean War scenario. Palmerston, who led the British in the attack on Russia in 1853 in the Crimean War, had the idea of pushing Russia out of the Black Sea. This was Brzezinski’s idea, laid out in the grand chessboard in his book 1997. The Russians saw, oh my God, the Americans have just done another coup, not the first time. There have been dozens of these operations. And we’re not suckers, so we’re taking back. We are taking back Crimea. That part, I think, is indisputable.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: The Western reaction to the takeover of Crimea in 2014 was pretty well, not too strong, I would say it was pretty comparatively. And a lot of people argue that that mild reaction encouraged Putin then to fully invade Ukraine in February 2022.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No, this I disagree with, as it may.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Does it. What about the justification for the full scale invasion of Ukraine despite all these grievances, despite what it looked like from the Russian point of view? Of course, one has to see that. But does it really justify a major war in Europe and trying to shift borders by force and violence and to attack civilians? You know, all the terrible battlefield scenes we can still witness every day?

The Path to War and Missed Opportunities for Peace

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: It’s a little more complicated even than this because of the following. In 2002, the United States unilaterally abandoned the Anti Ballistic Missile Treaty. This was probably the single most destabilizing event in the 21st century for US-Russia relations. Russia thought, okay, the United States is abandoning the core principle of how we maintain deterrence. And this was done unilaterally.

In 2010, the United States started to put in, against heated Russian objections, anti ballistic missile silos, the Aegis missile systems, first in Poland and then in Romania. In 2019, the United States unilaterally abandoned the Intermediate Nuclear Force Agreement. So from Russia’s point of view, what the United States was doing step by step was coming to Russia’s border with the US military and its missile systems.

According to Ray McGovern, the former CIA analyst, he describes how in January 2022, Blinken Secretary of State said to the Russian Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, that the United States reserved the right to put in missile systems wherever it wanted as long as the host country agreed, including Ukraine. I wasn’t party to that conversation, obviously, but the interpretation is consistent with everything I know because I did speak to the White House in December 2021, begged them to negotiate rather than to continue what was a sure path to war.

I said in December 2021 to Jake Sullivan, announce that NATO will not enlarge to Ukraine and you can avoid the war. And he said to me, no, we will not announce that Ukraine cannot enter NATO. He actually said to me, don’t worry, NATO’s not expanding. I said, Jake, NATO’s not expanding, but you can’t say it in public. He said, yes. I said, well, then you’re going to have a war.

And in January 2022, when the United States refused to rule out even putting missiles, missile systems into Ukraine and when there was a continued massive military buildup of the Ukrainian army, and this we really need to understand as well, because it became a several hundred thousand NATO armed unit that was attacking the Donbasses. Everybody, including the OSCE observers say Russia said, we’re not going to permit de facto or to slide into being surrounded by the United States.

So I’m going to answer your question the following way. The war could have been avoided so many times had the United States taken an honest position. And then something that I do think is absolutely important and also not part of our understanding and discourse. What was Russia trying to do when it invaded on February 24, 2022? I’ll give you my interpretation. They were trying to scare the wits out of Zelensky that he would agree to neutrality.

Because what happened, in fact, was within about a week of the invasion, Zelensky said, oh, you know what? We don’t have to join NATO. We could have neutrality. And within two weeks, actually, the Ukrainians approached the Russians and said, you know, we don’t have to go on with this. And the Russians said to the Ukrainians, give us a document of what you have in mind. And they did. And that document went to President Putin. And President Putin said, you know what? We can negotiate on this basis.

And what came immediately was negotiations under the auspices of Turkey, and this became known as the Istanbul process. I have had extensive discussions with the Turkish diplomats about this. So on March 28, Ukraine and Russia issued a joint communique. This is March 28, 2022, issued a joint communique saying, we have a framework for peace. And it was based on Ukrainian neutrality. It was based on Crimea being outside of the agreement. In other words, Russia is not going to negotiate that. And it was based on essentially implementing the Minsk 2 agreement in the Donbass.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Doesn’t that all sound as if you were defending Putin for invading or making up?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes, I’m. Yes.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: I mean, option. But to invade?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No, no, no. What I’m explaining is that this war could have ended in about two. Well, the war starts in 2014, by my chronology, but the invasion February 24th, could have ended in two weeks because it was a ploy to force the neutrality back onto the agenda, which Putin had tried to do in December 19, 2021.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: What about the long. The long rows of tanks which were heading towards Kiev, trying obviously to topple the government in Kiev?

The Missed Peace Agreement

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No, no, I wouldn’t say that. What they were trying to do was intimidate the government, and they were withdrawn as soon as that document was exchanged. That’s what actually happened. They were trying to intimidate Zelensky. And, you know, this is really important from my point of view. I said to Sullivan in December 2021, Ukrainian neutrality is not a concession. It’s a benefit for everybody. It’s a benefit for Ukraine. It’s a benefit for the United States. It’s a benefit for Russia. Keep a buffer between the two superpowers. Don’t press your luck, Jake. No, no. Anyway, Ukraine’s NATO is not expanding. But he wouldn’t say it in public because they didn’t mean it. Of course, they wanted to do what they wanted to do because they were playing poker.

And to my mind, just to explain on April 15, 2022, this is basically eight weeks after the start of Russia’s invasion agreement was reached, with a few clauses still to be finalized. And you can find that online. The New York Times published the agreement. They were close to ending the war. Now, we know that the United States stepped in at that moment and said, don’t do it. Told the Ukrainians, keep fighting.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Boris Johnson.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Boris Johnson came physically around that time, but, you know, the British are not independent agents in this. This was a US Policy that this war should continue. And why, again, I know why. I happen to see some of it. The US deeply believed that they were about to crush the Russian economy, that cutting Russia out of SWIFT was going to bring the Russian economy to its knees. They really believed that. I talked to a lot of senior U.S. officials at the time. I never believed that. I had never seen sanctions actually lead to a fundamental political change in the sanctioned country. It usually is a reason for those governments to toughen up.

So in any event, they believe that Russia was not going to survive any of this. So they made the gamble and the Ukrainians bought into it. We don’t have to agree to this treaty. Incidentally, Naftali Bennett, who was the prime minister of Israel, was informally acting as a mediator alongside Turkey. And Bennett gave a remarkably open and kind of discursive interview a couple of years ago where he said, yeah, there is agreement was close, but the United States stepped in and said no. And then Bennett said they did it because they thought they would look weak to China. So that this became something about sending signals, looking tough and so forth.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: A lot of people would say, you have a very benign interpretation of Putin’s motives and what he was after.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I do, yeah. You know why? Because all during this 30 years, the United States had the upper hand. And the United States used the upper hand in a very arrogant way. It launched wars in Afghanistan, in Iraq, in Syria, in Libya. It made coups. It abandoned the nuclear arms framework unilaterally. So I put most of the onus on the United States.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: But not all of it.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Well, not all of it, but I put most of it on the United States. No one’s perfect.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Would you say that Putin’s invasion was totally unjustified and created a lot of misery and death, which was not necessary at all, and was really. That he needs to be blamed for that to provoke a major land war in Europe? After all, what happened before, after the two worldwide world wars we had in Europe, was, you know, basically very despicable. Cannot really be excused in any way.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No, I wouldn’t put it that way. For reasons that I’ve explained. The intention was not a major war. The intention was to get to the negotiating table and it succeeded. And the United States, similarly, was quite despicable in overthrowing a government or participating in the overthrow of a government. It was quite despicable in launching a CIA operation to overthrow Syria, was quite despicable in bringing NATO in to overthrow Gaddafi.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: We don’t want to balance now who is more despicable.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No, no. But my point is, you know, in general, in general, in life, the more powerful country calls the shots. The United States believed that it was the sole superpower. Biden, absolutely to the end, believed that. He cited this repeatedly. It’s not surprising that the powerful country makes most of the abuses, frankly. That’s arrogance. That’s the arrogance of power.

Paths to Peace in Ukraine

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Let us jump forward a little bit towards the present and the still continuing Ukraine war and the attempt to overcome it and end it, to at least get a ceasefire. And all parties apparently seem to be interested in that. Though, of course, there is a lot of suspicion in Western circles whether or not Putin is serious or whether he just says so without really meaning it, because he is militarily, at the moment, probably a little bit more successful than the Ukrainians. How do you envisage that the war can be overcome? And should Ukraine really be the loser, losing territory, having to give up its natural resources to the United States to a large extent, while Russia probably will be unsanctioned? Would that all be the right way forward to you, according to you?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I think there are three issues right now. It’s the same three issues that were on the table in 2022. It’s the same three issues, essentially, that have been on the table with the Minsk Agreements as well. One is the question of Ukraine’s military alliance or not. I have always believed that the only solution to this war is Ukraine’s neutrality. I’ve always believed Russia will never allow NATO on its border and that this should have been recognized by in the 1990s. We should.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: But NATO is already on the border of Russia in terms of the Baltic states.

Russia’s Position on Ukraine and NATO

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Right. But this is a 2,200 kilometer border, including, crucially, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. And so this is hypersensitive for Russia. And this is what Brzezinski knew all along, and it’s what Lord Palmerston knew all along. So the first point I’m saying is Russia will never allow Ukraine to be part of NATO. So either we have perpetual war or the defeat of Ukraine or an agreement on neutrality. I overwhelmingly favor an agreement on neutrality.

The second issue is security. There needs to be security guarantees for Ukraine, without question. But at the same time, it is absolutely also true there needs to be security for Russia. There needs to be collective security for Russia. This means they don’t want the CIA or the military or the missile systems on their border. And so that’s the Russian point of view. The Ukrainians, we don’t want to get swallowed by Russia. So there needs to be a security agreement. I think everyone agrees with that. The one point I personally would make is that it should be an agreement in the UN Security Council. This is the right place for it. Other countries, Germany or Turkey or India and others can join along with that, but this should be a UN Security Council security arrangement.

The third point is territory. And this is vexing, but it’s part of the tragedy of this whole story. First, Crimea is never going back, and nor should it. In one sense. The US played its hand, it blew it. It should never have done what it did, engaging in regime change. And Crimea, because of its fundamental national security importance for Russia, is not going back. Then comes the question of the four territories claimed by Russia. And here this is painful. It’s painful because Russia made no territorial claims on the Donbas and certainly not on Kherson or Zaporizhzhia until the fall of 2022. Never in 2014, never all the way through the Minsk agreements, not in the Istanbul negotiations.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: They did not annex these territories partially, four of them before the war actually started.

The Minsk Agreements and Territorial Claims

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No, no. What had happened was these were the people’s republics. They had broken away. And the idea that Russia was pursuing was autonomy for these regions. And that’s the Minsk II agreement. And it’s fascinating what the Minsk II agreement reflects. And I only understood this properly last year when I visited Bolzano in northern Italy, which is a region called South Tyrol, which is a German speaking region of Northern Italy, and it is an autonomous region in Italy, meaning that the central government of Italy does not control the governance of Bolzano. Bolzano does not pay the national taxes. It pays a kind of lump sum that’s part of an autonomy agreement. And it came about because there was a German speaking minority, an Austrian minority, that felt that it was facing discrimination by the Italians after World War II. It has a complex history, but finally it was agreed that it would be autonomous.

Now, who knew about that model very well, was Chancellor Merkel. She knew about it because she was very friendly with the politicians in South Tyrol, not surprisingly, given that it’s a German speaking population. And the governor, senior officials explained to me in detail last year that for Mrs. Merkel, Chancellor Merkel, the Minsk 2 agreement was modeled on the South Tyrol autonomy because Russia was not claiming territorial annexation. That only came from in September 2022. It was not on the table beforehand. What was on the table was autonomy.

And actually Germany and France, under something called the Normandy arrangements, were supposed to be the guarantors of Minsk too, which was voted unanimously by the UN Security Council and the United States. And the Ukrainians decided to blow off Minsk too, because Minsk 2 called for Ukraine to make a constitutional provision for autonomy of these two oblasts, Donetsk and Lugansk. And the Ukrainians didn’t want to do it. And so they never did it. It was never implemented.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: How likely is it that these three points which you just outlined, which are, according to you, the best way forward, that that will actually be done?

Trump’s Approach and Potential Peace Terms

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: So there’s two paths right now, and I believe Trump had his word on this one, which I don’t often do, but Trump says, look, either you accept the agreement that I’m putting on the table or the US walks away from this whole thing. Let the Europeans can do whatever they want, but if Russia can continue to fight, Europe can continue to support Ukraine, but the United States is not going to be a party.

This and what the US has said, apparently we haven’t seen the fine print, but it has said basically no NATO, some kind of security arrangement, though I don’t know the details of it. And some territorial exchange, maybe up to the current contact line, rather than the four full oblasts that Russia claims. We don’t know exactly the details. Now, in essence, the US is close, not far from the Russian position. Russia is saying, no, we need permanent neutrality. We need all four oblasts, and we need a security arrangement in which there aren’t European troops but are some other security arrangement.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Would that not leave Ukraine in a very weakened status?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Well, it depends. It depends what the details are. My view, my model actually for Europe in general is Austrian neutrality. In 1955, where the Soviets went home, Austria declared neutrality. We won’t join NATO, we won’t join anything. And the Soviet Union never bothered them again. Austria became an incredibly prosperous, happy country and to this day remains outside of NATO. I happen to like neutrality. I especially like neutrality that keeps the United States and Russia apart from each other. Because I don’t think superpowers should be in each other’s backyards, period.

Questions About Trust and Peace Agreements

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thank you. Whether Austria has the same or not a lower importance for Russia than Ukraine is very much the question. I think whether we can compare Austrian neutrality with the best way forward to Ukraine. I’m not sure even Putin would like that. And I’m not sure about other countries. I wanted to ask you many more questions, but we also have a few questions from the audience if I can bring in Emma, could you ask a selected question and ask it, please?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes. Dean Peterson asks, isn’t it an issue that Russia can’t be trusted to stand by a peace agreement? Ukraine talks about wanting a security guarantee to agree to peace lest they be invaded again. If Putin wanted peace on this agreement you mentioned, he could get it with Trump, but he keeps making many more demands.

Sure. Again, I think the United States is the least trustworthy country from my experience. And that goes with the arrogance of power. The US walks out of one treaty after another. Russia does not. The United States walked out of the ABM Treaty. The United States walked out of the Open Skies Treaty. The United States walked out of the Intermediate Nuclear Force Treaty. The United States has overthrown about 100 governments and regime change operations. So I’m not impressed at just pointing the finger at Russia.

There have been many, many treaties that Russia is still in that is abided by. And I go with the dictum of President John F. Kennedy in his wonderful peace speech in June 10, 1963, when he says that great powers can be counted upon to observe those treaties and only those treaties that are in their interests. And so if we make a good treaty that is in Russia’s interest and in Ukraine’s interest and in America’s interest, it will stick.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thank you. Sivan, do you have another question?

Ukraine, the EU, and NATO

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes. Along this same line, Prabha Fernandez asks if it would have been acceptable for Ukraine to join the EU rather than NATO.

Yes, I think the answer is yes. The issue, though is the EU made a bad mistake in its modern history. It became basically the same as NATO, almost informal legal terms. The EU NATO relationship is not some independent, distant relationship. Being part of the EU is pretty much tantamount to being in NATO. Being in NATO is pretty much tantamount to being in the EU.

And one of the saddest mistakes for the European Union is that it co-located NATO headquarters and EU headquarters in Brussels. And that’s not a coincidence. They became the same thing. And that is where the problem was we never had just a straight proposal to join the EU, never. Because already in 2008, the United States was pushing relentlessly for NATO enlargement. And NATO fell into line because this is a U.S. led alliance. So your question, a good one, was never tested and never asked.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: The EU is militarizing, as some people say, you know, they’re developing their own somewhat stronger defense policy. Would that not be a concern to Putin? Would he really be happy with Ukraine joining the European Union in its new, stronger military form?

European Security and Russian Concerns

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I personally believe it’s fine for Europe to have its own autonomous security and military, not to go marching off to war, but as a credible deterrence. I personally would be perfectly more than satisfied with NATO ending and the EU having its own military security. Russia’s not going to obsess about that. What they’re concerned about is the United States, which is a nuclear superpower.

We have along with Russia, we’re the only two countries that have 1600 actively deployed nuclear weapons. The United States has nuclear capacity and many other space technologies and so forth that Russia fears about a decapitation strike or other existential threats to Russia that the EU would not cause. So for the European Union to have deterrence, in my view, is fine.

And I think whether I like it or not, NATO very well may not exist in 10 years from now. In any event, Trump has little interest in it. And I think that Europe wants and needs some kind of strategic autonomy. Where I fault the European leadership tremendously is that they should engage in diplomacy with Russia. They haven’t even tried. They literally have not tried. They have not gone to Moscow, they have not met with Lavrov, they have not invited Lavrov to meet with them. They have not tried at all to have diplomacy for years.

Russia’s Responsibility and Eastern European Concerns

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Right, I take that. But we are talking about kind of all the time what the US should do, what the Europeans should do, and not wrongly, partially. But isn’t there something Russia should do as well? When you look at Eastern Europe, there’s real anxiety about Russia, real or perceived anxiety. You look at the Baltic states, they are seriously worried. Poland has pushed up its military defense, not because they like to spend money, but they feel threatened.

Norway, Finland and Sweden have joined NATO, and there is general anxiety around. And that comes not out of nothing. You know, Putin in particular has gone into Georgia, into Moldova. He still occupies part of it. Then, of course, what we discussed with Crimea and the full invasion and whether you try to explain that, that there are good reasons for all that. But there is still a lot of anxiety. And Russia is perceived as an aggressive country. What can the Russians do to actually reassure their immediate neighbors that they are not aggressive, that all that perception is totally wrong. So Putin needs to deliver something as well. And I think we haven’t talked about that at all. We only talk about what can do. What can Russia do?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I have to say just, you know, an example with Georgia. It’s not that Russia was the aggressor to Georgia. It was the same story in 2008. I don’t want to quibble in details, but I watched Saakashvili provoke this disaster. I absolutely watched it close up. It was quite shocking. The guy was crazy, in my view. I actually went left a talk that he gave at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, called my wife and said, this man is out of his mind. That was May. And then the war came the next month. So, Georgia, I don’t put as.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: We don’t want to discuss Saakashvili here.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I know the Russian.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: No, the Russians still occupy two parts of Georgia. They could have withdrawn meantime.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Okay.

Russia, Diplomacy, and Baltic Security

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Okay, what I believe, absolutely, there should be diplomacy. But one of the things I’ve always said to the Europeans is you’re worried about Russia. Okay, understandable. Ask Lavrov the very question that you just asked me. What is the security for the Baltic states? I’d like to hear from Lavrov. He’s an extremely intelligent person. What are you going to say? You’ve given a good challenge. That’s an absolutely appropriate thing to ask the Russian side. How can we trust you? Why should we trust you? What kind of security arrangement should we have?

Now, let me say something about the Baltics, by the way, because all of this requires detailed context. Latvia has a 25% Russian population. Estonia has a 20% Russian population. Lithuania has a 5% Russian population. You would think, I would think that being on Russia’s border and with a substantial Russian minority population, you would take some prudence. You would take some care.

And again, I want to explain where I’m coming from. I advise the Estonian government. I help them. I have a high national award from Estonia. I like these countries. I’m no enemy of any of these countries. I’ve worked with all of them. But they are cracking down on their Russian population. They are outlawing education in the Russian language. They are cracking down on the Russian Orthodox Church. The president of Latvia literally posted “Russia must be destroyed.” He posted that. “Russia delenda est,” you know, playing on Cato. Are you kidding? Come on, let’s be grown ups.

Let’s sit down and seriously ask the question, what can we do for collective security? It’s a very good question. I think there’s a lot that can be done. I’m a huge fan of the OSCE, by the way, or used to be, when it existed, which is very different from NATO. It’s got a completely different concept. The concept is of collective security. The concept is you don’t join a bloc that threatens your neighbor.

So in any event, I think your question is an absolutely fair one. The Russians say things they don’t get reported. I would like the Europeans at least to try. Has Kaja Kallas gone to the high representative, Vice President? Has she gone to Moscow to talk to Lavrov? No. Has she invited Lavrov to Brussels to speak with her? No. Why not? That’s what diplomats are supposed to do. I love diplomacy. I like talking with each other.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thank you. Emma, do we have another question?

Russia, NATO, and Missed Opportunities

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes. Heading back in time, Svetlana Savoranskaya asks: In 2000, Putin mentioned to Clinton that Russia wanted to join NATO. And Clinton spoke approvingly of the idea. If Gore had won and there was no war in Iraq, was there any chance of even some kind of associate membership for Russia? What was the impact of the Iraq war on the global order?

Yes, excellent questions. Putin said something in an interview in Le Figaro in 2017 that I think is really smart and interesting. He said presidents come into office with ideas and then men in dark suits and blue ties come and tell them reality, meaning the CIA or the US security state, and then he says, and you never hear those ideas again.

So apparently this conversation took place that Putin said, yes, I’d like to join NATO. And Clinton said, well, yes. And then he later quickly said, well, no, because he was advised by the US Security state. So the US Deep state, which I believe in that concept, meaning the CIA, the Pentagon, the other intelligence agencies, the NSA, the National Security Council and the Armed Services Committees in the Congress, they have viewed Russia as either a threat or a ripe piece of fruit that’s going to fall into their lap.

Ever since 1991, they were not out for good relations with Russia. They were out to basically make Russia fall apart or regime change in Russia. Brzezinski had the idea that Russia would collapse into a kind of three-part weak confederation and so on.

So, yes, if the United States had treated Russia with respect, if they had seriously talked about NATO, which never was seriously considered on the US side, things could have been different. My own experience as a much younger person back in 1989-91, working and admiring enormously Gorbachev and Yeltsin was they just wanted normal relations. They wanted to end the 75 years of this wrong direction that Russia had taken in the 1917 revolution. They wanted peaceful relations throughout Europe. Gorbachev was, if anything else, a man of peace. And the United States just couldn’t treat the other side with respect, dignity, and peaceful relations. It had to be on American terms, beginning to end. That’s, in my view, the mistake.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thank you. Have you met Putin?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Actually, I’ve met him on a couple of occasions, but never had long talks with him. But I know many, many other Russian leaders well.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: But you didn’t have the chance to look into his blue eyes.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: No, I did look into his eyes, and I said hello. That was it. But never a long conversation.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Sivan, do we have another question?

Multipolarity and the Future Global Order

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes, we do. So this comes from Brian. He asks, given current disillusionment with American foreign policy, are there historical examples of a different path that you wish would be reinstated in the new global order?

This is a fundamental question that comes to some of the big questions at the opening of our discussion. I think we are in a new era, and Secretary Rubio said it early on, as in his position as Secretary of State, that we are now in a multipolar world. Now, what multipolarity means is that there are many centers of power. The United States, Russia, China, and India, at the least, are centers of power.

If Europe ever gets its act together, it would certainly be a superpower. Right now it’s a divided 27 countries, but it’s a $20 trillion economy and a very sophisticated economy. So it would be a superpower too, with nuclear arms in France.

I think we’ve been multipolar for a long time and that the United States exaggerated its power for a long time, but now it’s recognized that we’re in a multipolar world. But what’s not agreed is what is the implication of that? Is the implication that now the great powers are going to go after each other? Is the implication that they’re each going to respect their own turf, but act like bullies in their own neighborhood?

Is it going to be that we’ll have multipolarity and multilateralism, which is a completely different concept. Multipolarity means there are several powers. Multilateralism means that there is an international rule of law. I’m in favor of multilateralism. I work for the UN. I work with the UN. I believe in the UN. It’s extremely weak. I would like to see it strengthened. To my mind, that would go a long way to making the world a safer place.

So I want to move to a multipolar, multilateral world. The United States psychologically has a hard time with this. If you read Foreign Affairs magazine, as I do every issue, most of the articles in most of the issues are to reassure the readers that America still is number one. It still dominates China. China’s still far from this. China’s economy is about to collapse and so forth. None of which I believe for a moment.

But I think the United States, psychologically, in our ideology, we have been the leader for a long time—this the American century. We’re the sole superpower and so forth. I think we have to come to the understanding that there can be other powers that are not our enemy. I don’t view China as an enemy. I don’t even view it as a threat. By the way, China can’t invade the United States. China can’t defeat the United States. But at the same token, the United States can’t invade and defeat China. This is two great powers, and I think there’s a lot of mutual benefit in good relations.

So that’s the kind of world that I would like to move to. Multilateral, stronger United Nations. I’m not in favor of the sovereignties argument, which is the Trump administration argument, that a great power like the United States requires freedom of action. We do what we want. No one tells us what to do, least of all the UN. That point of view, I don’t agree, because I believe that we rightfully bind ourselves to international agreements so that we can cooperate with each other and reduce conflict. That’s why we have the rule of law. That’s the Hobbes-Locke idea of the social contract, which I believe we need at the global level.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thank you. How can you be so sure that we are moving towards or have already arrived at a multipolar world? Doesn’t it look at the moment as if we were heading towards a new bipolar world? Only this time China and the United States, or the United States and China? Because the European Union, as you rightly said, isn’t really on the same level. Neither is Russia, I would say. And India isn’t either. So isn’t it really still bipolar with lots of disciples to each of these powers?

The Economic Basis of Multipolarity

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I tend to look at this through an economic lens. So I look at the size of the economies, at their productive capacity and of their likely trajectory. And when I do that, I don’t see China, for example, as becoming the world’s hegemon. Certainly not. I don’t see the United States disappearing from sight.

I do see India becoming much more powerful because it’s going to be the most populous country in the world by a wide margin. Maybe it will be 400 or 500 million larger than China within maybe 30 years. I don’t have the UN projections immediately in front of me, but it’s going to go to 1.7 billion, whereas China’s peak—and China’s on a trajectory to get to under 1 billion people by the end of this century.

So when I do the kind of back-of-the-envelope calculations, China’s share of world output is basically peaking about now because of the population decline that’s coming. India’s will rise, Africa’s will rise, and Europe is going to get its act together somehow. I don’t know whether it’ll be now or five years or 10 years. But Europe is a civilization, even though it’s fought itself for 1500 years, ever since the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but nonetheless, Europe will get its act together.

So we’ll be in a multipolar world, not a bipolar world. For the moment, the US and China definitely lead, for example, in AI, in many key technologies. But I was just in India last week. The progress is very rapid. The scientific and technical skills are rapid. The India space program is rapid. Technology diffuses. Smart people are all over the place. If there’s peace, there will be what we call economic convergence, which is that the poorer countries will grow faster than the richer countries.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Talk to us briefly about how you see the China-US relationship. You know, in the US there are still lots of anti-China hawks around. And also in China the suspicion of the United States is pretty high.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Absolutely.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: And so how is that going to develop? Do you see military conflict or do you believe military conflict, for example, about Taiwan, can be avoided successfully?

US-China Relations

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: First, from a kind of normative point of view, I do not view China as a threat, as I explained, and I do not view trade with China as a losing proposition. From the United States point of view, I view it as a win-win for China and the US.

I’ve been going to China now for 44 years. I’ve watched the development. Chinese people have worked extraordinarily hard and long hours. They’ve educated their young people. They have built tens of thousands of kilometers of modern infrastructure. They’ve saved at extraordinary rates. In other words, they’ve worked very hard for what they’ve achieved. I admire it. I admire Chinese civilization and I think we would do well to have good relations with China.

Is that the way things are going right now? No. The United States views China as, in Graham Allison’s description of the Thucydides trap, as the danger of a rising power coming to claim America’s crown. Of course I don’t view the world that way. I don’t think there’s one crown, I think there’s one planet and we ought to cooperate on it. But if you’re really obsessed with the question of who’s number one and who’s number two, well then China looks like a threat to you.

So the United States views China as a threat and this can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. John Mearsheimer, who I regard as a really great political scientist and a very dear friend, says yes, you know, as China rises, conflict with the United States is inevitable. He doesn’t mean violent conflict inevitable, but he says it’s possible. And I said, “John, but it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy to say that.” And he said, “Yes, that’s right.” I said, “John, why do we need a self-fulfilling prophecy of conflict?” He said, “Because that’s how the world is.” His book is called “The Tragedy of Great Power Politics.”

I refuse to accept tragedy as our baseline. I want cooperation and I want us to consciously aim at cooperation. But first, to tone down the fear mongering, I would like some American congressmen to get a passport and go see China and understand it a bit rather than just railing against it in Washington.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thank you. We have a few minutes time if you are not exhausted yet. Jeffrey, can I ask Emma to ask the next question please?

China’s Role in Global Security

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes. On the note of China, Andrew Pruden asks, China beats the U.S. in many national security industries, for example, 90% of all global shipbuilding. And the U.S. is no longer capable of acting as the arsenal of democracy in a future great power war. If tariffs are not the key to revamping US industry and manufacturing, what steps can the US take not to go to war?

This is clear. We shouldn’t think that we’re preparing for war. We are absolutely, absolutely as safe as a country can be in this world with, as Donald Trump says, two big oceans and a nuclear arsenal and a powerful military. We’re not going to be invaded. China could not invade us. China could not defeat the United States under any circumstance. And we shouldn’t plan on defeating China.

So we should engage in diplomacy because we have mutual deterrence, and that’s good. And mutual deterrence means neither side can defeat the other side. We don’t need an arms race to secure that. And we should chill out a bit. We are very powerful. And powerful enough to defend ourselves. Not powerful enough to run the world, but who wants to run the world? Let the world run for each place and let’s have peace.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thank you, Sivan.

Taiwan and the One China Policy

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Yes. So this is an anonymous question, and it asks about how you mentioned earlier the idea of neutrality for Ukraine as having worked for Austria in the past. How do you think the issue of neutrality, which seems to be impossible for Taiwan, would shape up in the kind of trilateral PRC, Taiwan and US relationship?

The difference with Taiwan is Taiwan is part of China. Interestingly, there are two governments, one in Beijing, one in Taipei. This is the legacy of China’s civil war. Both of them unequivocally said there is one China. They argued the Republic of China in Taipei about who rules China. They said, we rule. Of course, the PRC say we rule. Both agree there is one China.

When the United States recognized the People’s Republic of China, it, like every other country that has diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, which is essentially almost all the world, adopts the One China policy. It agrees that there is one China. The United States should not intervene across the Taiwan Straits. That’s the best safety for Taiwan.

Ironically, it’s analogous structurally to all the problems I was discussing about Ukraine. If the United States says to Taiwan, we protect you, we defend you no matter what, and some Taiwanese president or politician says, okay, then we’re independent because the United States has our back, there will be war. If instead there is prudence and there’s no independence declaration, there’s no attempt from the point of view of Beijing to break up China, then there will be peace.

The best way to protect Taiwan. It’s a little ironic, but it’s the same as what happened in Ukraine. The best way to protect Taiwan is for the United States to stop its meddling and especially to stop shipping armaments to Taiwan. China would lose enormously if it invaded Taiwan, and it won’t invade Taiwan unless Taiwan declares independence, in which case it will invade Taiwan. And that is the basic structural situation. The United States should not provoke a disaster.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Once again, a very controversial view that the US should not provide weapons to Taiwan.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I think it’s the most safety we could give to Taiwan.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Strategic ambiguity is still the policy you would endorse, I take it?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I don’t agree with that. I don’t agree with ambiguity as being helpful at all. I believe in clarity and I believe the United States should say clearly, we believe in one country, one China policy. We believe in peace across the state straits. We would regard a Chinese military action against Taiwan as being disastrous for China, for Taiwan and for the world, and we strongly oppose it. But we do not interfere by shipping weapons.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Taiwan, the one China policy is official American policy, isn’t it?

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: It is, but it’s not treated that way or it’s, you know, this is why the ambiguity to my mind is not so clever. I would just be explicit.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Okay, thank you. Can we take two more questions and then we go because you must get tired.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Maybe one more if that’s okay.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: One more question. Emma, would you be so kind.

Federal Reserve Independence

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Jumping back to an earlier discussion on tariffs and the Fed and criticisms with the Trump administration, will Trump succeed in replacing Jerome Powell before his term ends in February 2028? Given the GOP’s current majority in the Senate, would it make sense for Trump to try to replace Powell before the 2026 election since the Senate would have to confirm his nomination? If not, who is he likely to nominate to replace him in 2028?

Well, very good questions. Let me just say that the Fed’s independence is important and it’s very important that we not have one person rule in the United States. So if the President can set tariff rates, if the President can start or stop wars by himself, if Congress abnegates all responsibility, if independent agencies like the Federal Reserve lose their independence, we lose a lot of the functioning of our system, which going back to the brilliance of 1787 in Philadelphia was based on checks and balances, which I continue to believe in.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Jeffrey Sachs, it has been a great pleasure. We have disagreed on quite a few issues. But the last point you made, I think we all can full heartedly agree with. It has been very interesting to talk to you and thank you for your interesting and provocative views at times and thank you for making the time. I know you are in Rome. It’s even later in Rome than it is here in the US. So please have a good night and thank you so much.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Well, great to be with you and thanks to everybody for participating and for the wonderful questions.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Also, thank you very much for coming and joining us tonight. Here at the Krasno Global Event Series. I would like to thank our audience for staying with us till the bitter end. And there will be new Krasno events next semester. But for the time being, I wish you all a good summer. And thank you very much again to Professor Jeffrey Sachs for joining us today. Bye bye.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: Thank you. That was a lot of fun. I really appreciate it.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Enjoyed it too. Thank you for your interesting views.

PROFESSOR JEFFREY D. SACHS: I hope we have another occasion sometime soon.

PROFESSOR KLAUS LARRES: Thanks a lot.

Related Posts

- Nick Fuentes’ Interview on Tucker Carlson Show (Transcript)

- Transcript: Zohran Mamdani on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart

- Transcript: Zohran Mamdani’s Historic Final Rally Speech Before NYC Election

- Transcript: President Trump’s Remarks At Cambodia-Thailand Peace Deal Signing Ceremony

- Transcript: Marjorie Taylor Greene on 5 Pillars of MAGA – Tucker Carlson Show