Read here the full transcript of Peter Kreeft’s lecture titled “10 Influential Philosophers and Why You Should Know What They Said.”

Listen to the audio version here:

TRANSCRIPT:

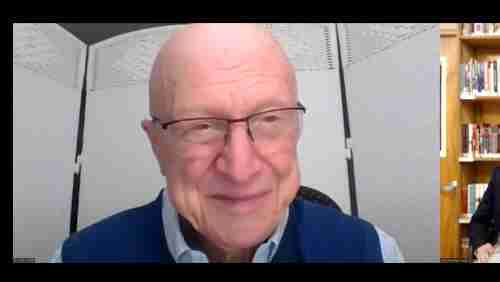

DR. PETER KREEFT: All right, well I thank you for this opportunity and I thank you for giving me my topic. It’s a very broad one, at least limited to 10. The last time I was asked to talk about my 10 favorite books I got up to 30 and then I noticed that I had used up all the time, so I’ll confine myself to the 10 greatest books of philosophy. I don’t want to use a scholarly standard.

If I were writing a history of philosophy and I can only include 10 philosophers and they were supposed to be the most influential, I would include some of the ones I’m going to talk about tonight, but I will also not be able to omit certain very influential philosophers that I would not talk about tonight because I don’t think they are as wise as the ones I’m going to talk about. For instance, Descartes, Hume, Kant, Hegel, Freud. I’m going to talk about Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Boethius, Thomas Aquinas, Pascal, G.K. Chesterton, Dostoevsky, Tolkien, and C.S. Lewis.

The last three or perhaps the last four are not usually classified as philosophers, but if philosophy is, as its inventors said it was, the love of wisdom, then that must be our standard. What delivers the most wisdom? Well, to me, these 10 thinkers and these 10 books have delivered more wisdom than any other.

Plato and The Republic

We begin with Plato. Philosophy begins with Plato. It’s amazing that Plato, who is the first philosopher whose complete books we have. We have nothing by Socrates. Like Jesus, Socrates wrote nothing.

I have tried teaching philosophy to freshmen in many ways, all possible ways, and some impossible ways, and I’ve found none that can even come close to the effectiveness of introducing them to Socrates through Plato’s dialogues. That’s not to say that I classify myself as a Platonist or a disciple of Plato or confine myself to Plato’s answers, but Plato’s strategy of doing philosophy in dialogue and Plato’s brilliant psychological understanding of human character, a dimension that philosophers often get because they’re absent-minded and impersonal. And above all, the figure of Socrates, an example of philosophy, very, very impressive.

And of all Plato’s works, by far the most important and influential is the Republic. That book is certainly the most famous and influential philosophy book ever written. Even though most of it is about politics and almost nobody agrees with Plato’s politics, it’s a kind of a benevolent dictatorship, a rather rigid class system based on a rather rigid ideological framework. Nevertheless, Plato’s charm in raising the question, whoever you answer them, is, I think, unparalleled.

There was a philosopher, I think his name was Sidney Hook. He’s a New Yorker and he was an atheist, and in his autobiography, he wrote about how he became a philosopher. He was a non-conformist in high school. He skipped most of his classes, but he was very smart. He spent most of his time in the 42nd Street Library in New York City, reading whatever book he randomly picked. And one day someone said to him, “You gotta read Plato’s Republic.” And he said he read Plato’s Republic and he was hooked.

When he got to the most famous image in the entire history of philosophy, namely the cave, the cave of the intellectual equivalent of original sin that Plato says we’re all born into, we’re all born stupid. The need to get out of that cave and to obtain enlightenment, the reality and not just appearances, he said, so captivated me that it was my conversion. He said, “If that’s philosophy, I’m going to be a philosopher.” He did. And I’ve talked to students whose contact with Plato, and especially Republic, and maybe especially that image of the cave, has had a somewhat similar effect.

Plato is the great philosopher of supernaturalism. We mean by nature, everything that we can touch with our senses, we’re talking about something very big, like the entire universe. But then there are things that we can’t touch with our senses. And they always at least have objects that seem to be supernatural. The mind, for instance, it seeks truth, it seeks certainty, it seeks truths like being is not non-being, and three plus seven are ten, and justice is a virtue. Those things have no color, no shape. Physics can say almost nothing about them. They’re natural rather than supernatural to us because they’re part of human reason. And yet they reach out to and try to understand something that is not part of nature.

Truth. Truth itself. Truth is a capital T. Each of Plato’s dialogues centers on one of these truths which Plato called forms, or consensus, or Platonic ideas. They’re not subjective opinions, they’re objective truths. And Republic is one of the most important because its idea, its subject, is di chaosune, usually translated justice. The word is used in the New Testament, often translated by righteousness, fundamental moral virtue. Justice means each person and each power in a person doing the thing that it’s supposed to do and designed to do.

Justice is the virtue that regulates all the other virtues. Wisdom or prudence for the mind, and courage for the will, and self-control for the passions, all of that is justice. And the fundamental point that Plato wants to prove about justice in the Republic, to prove now, not just to suggest, prove beyond the shadow of a doubt, is that justice is always more profitable than injustice. That the thing that none of us want all the time, namely moral righteousness, we want it all the time we can’t, is identical with, or at least the only pathway to, the thing that everybody wants all the time, happiness.

If you’re good, you’ll be happy. If you’re not, you won’t. Gratitude. But it’s a very profound gratitude. And Plato tries to prove it conclusively, both for individual souls and for states, which he says are created in the image of souls, because it’s human beings who create states in their own image.

Most of the details are political. The psychology of Plato has vastly outlasted the politics of Plato. For instance, psychology, the map of the soul, distinguishes three powers, which almost every school of psychology in some form has. Mental power, mind, reason, understanding, wisdom, on the one hand, the passions, the desires, the feelings, the emotions, and then something that Plato calls the spirit part, which we would call the will, that which chooses, and that which fights for the true against the false.

Freud’s version of them is different than Plato’s, but it’s a threefold version, the superego and the ego, and it responds pretty nicely to Plato’s mind and will and passions. And it’s significant that almost all great epics of literature in the history of Western civilization have three protagonists, each of which specializes in one of these three. For instance, in The Lord of the Rings, we have Gandalf, the wizard, who’s the brilliant one. And we have Aragorn, the king, who is the ruler, he rules by authority and strength of will. And we have Frodo, the humble hobbit, who does most of the work.

And the brother Tarazza, we have three brothers. We have Ivan, who’s the intellectual, he’s an atheist. And we have Dmitri, who is very willful. And we have Alyosha, who is the priest, the humble one.

Plato’s influence has been enormous. If there hadn’t been a Plato, there wouldn’t be Aristotle. If there hadn’t been an Aristotle, there wouldn’t have been most of the other schools. In fact, in ancient Greece, and later in Rome, every philosophical school declared that it was the true inheritor of Socrates, Plato’s hero. Just as in the history of Christendom, each church and denomination claims that it is the true inheritor of Jesus. So in that way, Socrates is the philosophy, what Jesus is the religion.

So The Republic is his masterpiece, read it, it’s fascinating. It gives you things as diverse as a reputation of Jaffism, or moral and intellectual relativism and subjectivism, an argument for the immortality of the soul. It gives you a kind of a ladder of education to move up from the lowest to the highest. It gives you a metaphysic, a theory of nature of things, what it really means, a little bit of everything in it. So that’s the thing to start with.

Aristotle and The Nicomachean Ethics

Then move to Aristotle. Aristotle is the master of common sense. Great modern philosophers very rarely refer to Aristotle. And I was once puzzled about that, until I realized that most modern philosophers are very far from common sense. They’re all very smart, sometimes very wise, but very seldom do you get a philosopher of common sense, a kind of a Western version of Confucius.

Confucius, by the way, was the single most successful social reformer in the history of the world. Probably because he’s so boring, commonsensical. It’s basically Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood for Grownups. Worked for 2000 years, until Mao Zedong replaced it with the opposite philosophy of Confucius.

So a commonsensical philosopher like Aristotle gives you a commonsensical theory that is metaphysics and cosmology, anthropology, and also a commonsensical practice, ethics. And I found that my students are very apt at picking up Aristotle’s ethics, and very unapt at picking up the theoretical stuff. They’re both commonsensical, but I think that the typically modern or typically American mind is much more into practical things than theoretical things.

In any case, I’ll leave Aristotle’s metaphysics, or epistemology, anthropology, and the rest of his philosophy out of the discussion, and just talk about his masterpiece, The Nicomachean Ethics. It’s a series of class notes taken down by students, and probably edited by Aristotle. So it has the charm of listening to a university professor go over the same thing a couple of times, and return to old topics more than once, sometimes correct themselves, and yet it’s nicely organized.

It begins with the question, what is the true good? What’s the meaning of the word good? And Aristotle gives you a very commonsensical answer to that. A good is something that is desirable, either for itself or something else. And something that’s desirable for something else is a means, and something that’s desirable for itself is the end, and the means exist in order to get to the end. So the fundamental question for Aristotle is, what is the greatest good, or the supreme end? What is it that is supremely desirable?

The answer is happiness. Complete happiness, true happiness. The English word happiness is not a good translation of the word that Aristotle used for it, eudaimonia, because it suggests something that just happens by chance, like winning the lottery. But for Aristotle, happiness is something that doesn’t happen by chance. It has two parts, the part that comes from outside you, and the more important part that comes from inside. And if you fall sick and die, and if you experience great pain, and if terrible accidents happen to you, you’re not completely happy, of course. But much more important for Aristotle is what you do inwardly with what happens to you.

The habits of the soul, the mind, and the will, and the passions, can be either good or bad. And good habits are called virtues, and bad habits are called vices. And most of the Nicomachean ethics is about what are the different virtues and vices that fit human nature, and thus are natural, and which we need the most in order to give us true happiness, true flourishing.

He begins with what Plato identifies as the four cardinal virtues, prudence, or practical wisdom, and courage, or strength, will, and self-control, or temperance, namely the right attitude towards the past, and justice, as the proper ordering of all those virtues, and then adds about a dozen more, some of them very important, like friendship, others much less important, like a sense of humor, or wit, which Aristotle regarded as a virtue, although a minor one.

The book is so checkable out in experience, so empirical, so like a laboratory test manual, just as you take this out in your in your life, that it’s a touchstone of common sense, which is why it’s so relatively unknown today, certainly in the political arena, but know more about that later.

One of the charming things Aristotle says in comparing ethics with politics is that the ruler of a state must, of course, care about justice, but there’s one thing he should care about much more than justice, because what makes any kind of human community or society, including the political one, a good one, is fundamentally something more important than justice called friendship, which Aristotle defines simply as goodwill, which is quite close to the Christian notion of love as agape. Thomas Aquinas defined love as the will to the good of the other person. That’s the kind of common sense Aristotle had.

So I predict a very satisfying reading to Aristotle’s ethics. Plato’s reading is more challenging, more interesting maybe, and more controversial. Somebody, I think it was George Bernard Shaw, said that every little baby is born a little Platonist or a little Aristotelian, and in the most famous of all philosophical paintings, the School of Athens, we see all the Greek philosophers emerging through a portico from a building down some steps, and the two main ones in the middle are Plato and Aristotle. Plato was pointing up, Aristotle was pointing down, signifying that if you want to talk about talk about nature and the natural, Aristotle’s your man. If you want to talk about the supernatural, they don’t contradict each other, they just specialize in different things.

Augustine and The Confessions

When we get to medieval Christian philosophers, there are clearly two that are superior to all others. The two most brilliant and most influential and most profound Christian thinkers of all time are certainly Augustine and Aquinas. Augustine’s The City of God is the world’s first philosophy of history, and a profound philosophy of politics, and laid the basis for Christendom as a social and visible political order.

But the book that people love the most, in fact, the most beloved book ever written outside the Bible, according to almost all Christians, and the one most often quoted, is certainly the Confessions. There is nothing like Augustine’s Confessions. It is like a volcano, you enter that world and you get thrown around and tossed and turned, and you share his darkness as well as his light, and his as well as his reason, his entire life passes before you in a brilliant way, unparalleled until quite modern times.

He’s like an existential depth psychologist. Along the way, he deals with great philosophical problems, like how is it possible for a human being to understand the nature of God, and is there an absolute and unchanging morality, and how do we know it, and what about the problem of evil?

If God is so good and so powerful, why is there evil? And above all, how can I attain happiness? And the key and the summary to Augustine’s Confessions is the single line that is quoted more often than any other line ever written by any Christian outside the Bible, the very first pages of the Confessions. Because the Confessions, by the way, is written to God, and Augustine is talking to God when he says this, he says, “You have made us for yourself, therefore our hearts are restless and no way rest in you.”

That’s the meaning of life in a built sentence. The problem is the restless heart, and the solution, the explanation, is that it’s made for an end, the end that God alone has. That’s why we all have a lover tomorrow. And Augustine tried just about everything possible as an alternative to God, and proved by his own experience that it simply didn’t work.

And then came the realization that God had to do it. He couldn’t do it. He was searching with a profound mind and a profound will, with a great heart and a great head, but until a miracle of divine grace intervened, in this case in a rather spectacular way, in other cases equally necessary but not so spectacular, the conversion was not complete. The conversion of not just the mind, but of the will.

Medieval statuary almost always has Augustine extending his two hands outwards, and in one hand you see a heart on fire, and on the other hand you see a book, an open book, presumably a Bible. I don’t think there’s ever been a single thinker in the entire history of the world who had at the same time a more brilliant mind and a more passionate heart. If you read the Confessions, maybe if you’ve read it before but in a different translation, please read it in Frank Sheed’s translation. It is magnificent.

It’s poetry in prose, and that’s because it’s literal. I once wondered why modern translations of the Bible were so boring, and I assumed that it was because they were made by scholars who preferred literal accuracy to poetic fluffing it up. Then I checked it out and I found out that the older the translation was, usually the more poetic and the more literal it was. The old King James and Douai verses are magnificent, and certainly true of Augustine’s Confessions.

I never read a book, the translation of which made more of a difference. I read it in college, I was bored by it, I read Sheed’s translation, I was transported.

Boethius and The Consolation of Philosophy

Now before we get to Aquinas, let’s take another medieval thinker who was almost as famous and beloved and well-read as Augustine throughout the Middle Ages. His name is Boethius, and his little classic, The Consolation of Philosophy, was written in prison as he’s waiting execution on false charge.

And he asks the question, how can philosophy help solve the problem of evil and the problem of injustice, and why do bad things happen to good people? In a world ruled by divine providence, why do the righteous suffer? What can philosophy tell me about this? And what he does in this book is he synthesizes the wisdom of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, and other ancient thinkers together.

And when I teach it to freshmen students at Boston College, they find that it is the most surprising and unheard of and unorthodox book that they’ve ever read, and that’s because it’s so traditional and commonsensical and orthodox. In an age when radical rebellion is a new orthodoxy, orthodoxy is the radical rebellion. So this is a summary of ancient wisdom in service of a very personal and practical problem of how do I deal with evil? And how can I see all things as somehow coming under divine providence if they don’t seem to?

Brilliant book, fascinating book, easy book really, no difficulties in it, until he comes to the end and reconciles divine infallible predestination with genuine human free will. Brilliant way, which is obviously correct but easy to understand because time and eternity are two of the most difficult concepts we can find.

Thomas Aquinas and Summa Theologica

And then comes the greatest work not only of theology but in my mind also possibly ever written, the Summa Theologica or more properly Summa Theologiae by St. Thomas Aquinas, almost 4,000 pages long.

It’s not a book you read from cover to cover like a novel, it’s more like an encyclopedia, it’s more like an encyclopedia, but although it’s 4,000 pages long it’s incredibly condensed. For example, I know of no philosopher out of the hundreds who have dealt with the problem of evil who have formulated the problem of evil in a more succinct and condensed way than Aquinas. Before he argues for the existence of God, he offers two objections. One is the problem of evil and the other is the apparent adequacy of natural science to explain everything without God.

And the problem of evil is explained this way, if one of two contraries or opposites is infinite, there is no room for the other to exist anywhere. The word God means infinite goodness, therefore if God existed there could be no evil, there is evil, therefore God does not exist. It’s wonderfully succinct.

One of the most brilliant atheists of the 20th century, Bertrand Russell, says in his autobiography that he went to the Summa Theologica to get stuff from Aquinas that he could criticize, because he’s an atheist, because Aquinas is a famous theologian, and he came away very impressed, not convinced, but very impressed by Aquinas’s honesty in listing all the objections. He says, Aquinas summarized some of the positions that I held better than I could do, then refuted them.

There’s everything in the Summa. Everything from what is the meaning of life, let’s look at different candidates for happiness and explain why some of them don’t work and only one does, to details that are sometimes very, very concrete when it comes to the specifically theological stuff, like acrobats. Summarizing the Summa is like summarizing the universe.

I heard the story once of two English soldiers in World War I, French warfare, and one wanted to go AWOL, and he said, “I don’t understand why we’re here. What are we in this mess for?” The other said, “Well, we’re by the say of Westerners, we’re here to help the poor, we’re here to help the poor.” And the first says, “What’s Western civilization?”

And the first one, well, he couldn’t define it, he just gestured around, all this. So, the other soldier went AWOL. Difficult to define a big thing like civilization. Well, difficult to define the Summa. It’s a world.

What is its primary theme, probably, is the marriage of faith and reason, philosophy and theology, revealed wisdom and natural wisdom. Wisdom coming down and wisdom going up. The two sources of truth, fine truth and human truth. No one has ever done a more complete job of that than Aquinas.

And even though it’s highly abstract, yet if you once master the vocabulary, a half a dozen or dozen important words in Aquinas’ philosophical vocabulary, everything else is simple. The arguments aren’t long, they’re short, they’re direct, they’re clear, amazingly clear. I find Aquinas one of the easiest philosophers, artist. He has a reputation that’s not fair.

So, I advise you to browse around in the Summa, just to catch his mind and his method, his habit of philosophy. It’s eminently immutable. Each article deals with a single question to which there are only two answers, yes and no. And then he lists all the objections, and at the end he answers them.

And then he gives his reason, and he gives an argument both from authority and from reason for it. And he defines his terms clearly, and almost all the arguments are syllogisms, which is the easiest kind of argument to follow. So, have a good time browsing in the Summa. You won’t drown in it, but you’ll soon place it.

Blaise Pascal and The Pensées

Is Aquinas, though, the most powerful and effective apologist for Catholic wisdom through the modern age? And the answer probably is not, except maybe to philosophers and theologians. What is then? There’s a teacher course called Perspectives in Western Culture, a two-semester course, double credit course, in which we traced all the great philosophers and theologians in history, two semesters, for double credit.

And whenever I take a poll at the end of the course, and I had asked, who is the most convincing and interesting and impressive philosopher who changed your life the most, or changed your thinking the most? The most popular answer was Blaise Pascal. We read his book The Pensées. It is not a well-organized book, it’s a series of notes.

He died before he could organize it into a book, but the notes are absolutely brilliant, like little arrows piercing to your heart. And the two parts of The Pensées are basically the bad news and the good news. The bad news is how bad off we are, how stupid we are, how wicked we are, how foolish we are. And then the good news, of course, is that there is a way out of this, and it’s divine wisdom, and it answers all the questions that are unanswerable.

Why human wisdom? And he doesn’t convince you of this through long, complicated, technical, philosophical arguments, but by little zingers. The Pensées, meaning thoughts, consist in about a thousand, well, most of them are a paragraph long, sometimes only a sentence long, little zingers. You can read them over a cup of coffee.

And he’s a great psychologist of human foolishness. You look into a mirror when you read The Pensées, and you see the good news and the bad news, just as you do with every great theologian. I think the very first piece of Christian philosophizing and theologizing is, I think, Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. And everyone, every classic one since then has followed the same structure, the bad news and the good news, sin and salvation, problem and solution.

Pascal is much more skeptical of the ability of natural reason to prove God with adequacy. So he gives you, instead of a proof, what he calls a wager. One of the most famous arguments in the history of philosophy. Even if you can’t prove that God exists, you can’t prove that he doesn’t either. So what are your chances of happiness? If God exists and you believe in him, you get eternal happiness. If he exists and you refuse to believe in him, you miss eternal happiness. And if he doesn’t exist, nothing makes a difference after all.

There’s no life after death. There’s no eternal happiness nor unhappiness. So the wager is the world’s best bet. It’s much more than that. It sounds rather crass. And he’s coming down to our level as an argument. But students find it quite convincing.

And along the way, he refuses such as diversion, living for entertainment. Students who have their nose and their soul glued to their Facebook page or their phone are always, by Pascal’s, psychologizing this as a foolish kind of addiction. And the indifference that we have to great things, and the fascination we have for little things, ignoring our eternal destiny for the sake of worrying about a couple extra dollars on our tax form or getting a parking place. He’s very good at noticing things like that. I guarantee you, you will be struck.

I’ve tried to do with these two last thinkers, Aquinas and Pascal, a kind of bridge building the 4,000 pages of the Summa Theologica and organize it into about 500 pages, the philosophical part, with a lot of explanatory footnotes. And I thought it would be maybe too formidable for most people, but it has been selling very well. And ordinary people outside of college say it helps. They can understand it very well.

It’s the same thing with Pascal’s pensées. I tried to arrange the pensées in a logical order and comment on them. And that too, I think, is mainly because I let people themselves know.

G.K. Chesterton and Orthodoxy

Now, we come to contemporary times, 20th and 21st centuries. And my next four, my last four thinkers are not usually classified as philosophers. One of them is G.K. Chesterton, who I think is one of the most brilliant and unique minds in history. And his masterpiece is Orthodoxy.

In one sense, it’s the most unorthodox book. Orthodoxy simply means traditional Christianity. But he shows how revolutionary it is, how unorthodox it is, and above all, how it turns us upside down when we are standing on our head. He loves to puncture clichés. He loves to offer paradoxes, which are not just clichés, but illuminating.

I received in the mail once a large piece of paper, a newspaper size and a newspaper thickness, on which somebody had had printed the totality of this book, Orthodoxy, about 200 pages long or so, and thought it was such a great book that they wanted, I think he said 100,000 people. Maybe it was 10,000 people. I think it was 100,000.

This was back when a stamp cost three cents, and he got the thing printed for a penny each. So for four cents each, he could send this to 400,000 people. And he had $10,000 of his own money and he did it. Somebody thought the book was that good, to send it to all the people who’ve ever heard of, and they’ll convert people.

I won’t say anything else about Chesterton except that we either love him or we hate him, because when you meet Chesterton, he smiles at you, and he takes out a verbal and intellectual sword, and he said, “Let’s fight.” And he always wins, and he’s a good guy. He always wins, and eventually, your pants are down. You’re not bleeding. He doesn’t kill you. He just gives you unanswerable insights. Something like Pascal, actually.

By the way, when Pascal wrote the Pensées, he knew he was dying, and he gave away all his books. He was fairly rich and had a large library at the time, 17th century, except for two. He kept the Bible and the Confessions of Saint Augustine. Those are the two influences on both days. In contrast, Aquinas has read and understood and remembered just about everybody who has ever written anything before the 13th century, and it’s all somehow in his films.

So Orthodoxy is Chesterton’s masterpiece. There’s a second one called The Everlasting Man, also a masterpiece. It’s about the different pieces made in history.

Fyodor Dostoevsky and The Brothers Karamazov

And now my last three books are going to be novels. Philosophers don’t usually write great novels, and the three people that I’m going to push here, Dostoevsky, Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, are not professional philosophers, but they’ve written three of the best philosophical novels ever.

The Brothers Karamazov is, well, pretty much of everything. It’s a psychological novel, it’s a detective story, it’s a murder mystery, a religious book, it’s a theater book, it’s about human nature at its worst and at its best. What Dostoevsky does in almost all of his characters is stretches you. He stretches you in two opposite directions. You find yourself in heaven and you find yourself in hell. And he sees the good in the worst of us and the bad in the best of us.

And there’s not that much overt activity in The Brothers Karamazov. It’s 900 pages long. And, of course, there is a murder and a murder trial. There’s exciting stuff going on, but most of the drama is inward. And it’s simply brilliant. It’s fiery. At first you say, these people are crazy, and then you realize that you are these people and you’re crazy.

And the fundamental issue of The Brothers Karamazov is evil, the problem of evil. Why are we so evil? Why is there such a thing as original sin? And why does it seem to happen in families? Why do we seem to inherit? It’s not just individual.

On the one hand, Dostoevsky is a profound individual psychologist. On the other hand, he is very acute about the deep dependence of everybody on everybody. There’s a Russian word, sobornost, which has no English equivalent. It’s something like solidarity. I guess in Polish, it would be solidarinost. But it’s not just political solidarity, it’s spiritual solidarity, kind of a spiritual gravity that moves us.

One of Augustine’s great sayings is that, “My love is my gravity.” Amor meos, pondos meum. Gravity moves you. Destiny. And that’s true in The Brothers Karamazov. I remember Time Magazine interviewed, I don’t know how many now, a dozen, two dozen, supposedly the greatest writers living, this was back in the 20th century, asking them, what were the 10 greatest novels ever written?

And on every single list, and the authors are very, very diverse. There was only one that appeared on every list was The Brothers Karamazov. Not only the greatest novel, but the most Christian novel ever written.

J.R.R. Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings, to my mind, is an epic, not an epic poem, but an epic that is equal to The Iliad, The Odyssey, The Aeneid, Paradise Lost, or The Divine Comedy. It is not just a book for hippies. It’s not just a better version of Harry Potter. It’s epic that has everything in it. It’s genre, it’s fantasy, but then so is The Divine Comedy. Dante didn’t literally go through heaven, hell, and purgatory.

And one of the things, one of the many things that’s in that amazing book, which is 2,000 pages long, or 1,500 pages long, and thus as Tolkien himself said, unforgivably short, one of the things in it, not the only thing, is a kind of self-knowledge. You see yourself in the characters, in the most despicable character of all, Sauron, who is never seen. You see his eye, but you never see him.

But the addiction to Sauron’s ring exists in everybody, even in the greatest of the heroes, Frodo and Sam. And you feel that attraction to the ring and repulsion of it. You feel a double movement. In this way, the Lord of the Rings is not like The Brothers Karamazov. It changes you in two opposite directions.

And one of the things Tolkien can do that almost no other author a hundred times can do is make fascinating and attractive good characters, not just bad ones. Most of the characters in the Lord of the Rings are heroes, not villains. I don’t know any book ever written that has more attractive and identifiable heroes. At the same time, it centers on what you might call the psychology of damnation.

C.S. Lewis and Till We Have Faces

Finally, I get to C.S. Lewis, who to my mind is the most effective Christian apologist of modern times. And he has written many masterpieces, but I pick his best book, by his estimation as well as mine, as one of his last. It’s a novel called Till We Have Faces. And it happens in pagan times and pre-Christian times, as does the Lord of the Rings. And it deals at the center with a fundamental Christian problem, the problem of evil. Why in a universe run by God must there be so much suffering among the righteous?

Why don’t we have an answer to that question? He says, why must holy places be dark? Why do faith and reason seem to move in opposite directions? He takes a Greek myth, the myth of Cupid and Psyche, which is basically the myth of the romance between the human soul and God, and puts it into a concrete pre-Christian pagan story of conflict.

And you gradually see how profoundly Christian it is. And at the end, it gets, quite frankly, kind of mystical. Not misty, but mystical. It’s a book that inevitably you want to read twice, levels, many levels, and you always see much more in the second time than the first.

It’s not everybody’s favorite C.S. Lewis book. Chronicles of Narnia are probably that. They are simply the best stories ever written. And probably his most influential book that has done the most good is Mere Christianity. Every Protestant evangelical and every Catholic and every Eastern Orthodox person that I have ever talked to who has read that book has said that the Master Jesus may love it. And it’s done more for humanism than any other book ever written, I think. And it’s very, very simple.

It’s a series of broadcast talks during World War II to the little old ladies in tennis shoes who are staying at home while their husbands are being killed in prayer. So it’s very simple. Misleadingly simple. The arguments and the grammar are so simple, you say that it can’t be that easy. And like the Bible, it has a very clear surface, like the ocean, but immense depths. I must have read it 12 times. I guarantee you’ll get more out of it every time you read it.

Or if there’s one last book, it might be Lewis’s great masterpiece, his version of the Divine Comedy. If you don’t want to read Dante, and Dante is great, but fairly difficult. The Divine Comedy, brought up to date with a lot of modern psychology in it, and condensed to less than 100 pages, is The Great Divorce. It’s about a busload of passengers that get a chance, I don’t really believe they have a chance, which is a fantasy, they go from hell to heaven and they’re offered a chance to remain in heaven. And all but one of them gets to go back down to hell.

And this isn’t about us, it’s about our choices. Because one of the great mysteries of human life is why, when we know that doing the will of God makes us happy, do we rebel? Why do we choose God’s left hand instead of his right hand? He says to us, every time you’ve chosen my right hand, you’ve had joy. Every time you’ve sinned and chosen my left hand, you’ve had misery. So why do you keep choosing misery? And that’s a great mystery, and that little book answers that question.

I’ve seen it performed as a play on four different occasions, in four different cities, by four different sets of players, in four different ways, some with settings, some with no settings, to four different kinds of audiences. Every single time the audience is simply stunned. So that’s highly recommended.

So I’ve cheated a little, and I’ve given a couple of extras, but I’ve confined myself pretty much to 10, and I think I’ve confined myself to 45 minutes. I’m rather proud of that. I usually talk much too much. But now I’m not going to talk much too much. I’m going to shut up, and it’s your turn. Now comes the fun part.

Q&A Session

AUDIENCE: Thank you, Dr. Kreeft. I thoroughly appreciated the depth of each philosopher that you wanted to talk about, but also under the part of Aristotle, when you mentioned the virtue of friendship, I really like that, because friendship has been a huge part of my faith journey, and just seems like a very impactful line, that it is a very important virtue. So I really like that.

DR. PETER KREEFT: Thank you very much for talking. You’re welcome. Now we’ll open it up to questions that you have submitted, and if you’re still coming up with questions, feel free to continue submitting them in the chat. All righty.

AUDIENCE: The first question we have is from Brooke. For someone who wants to learn about philosophy, how do you recommend starting without getting overwhelmed?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Read Plato’s early dialogues. There’s a nice anthology called Great Dialogues of Plato, translated by Rousse. Nice, clear, modern translation. It includes the Apology, the Crito, the Phaedo, the Republic, and the Symposium. Or, if you want the Republic without politics, read the dialogue called the Gorgias, which I’ve observed changes people’s lives. But Plato is the answer.

AUDIENCE: Great, thank you. And the second question is from Andrew. He says you mentioned that humor is a virtue, though a lesser one. Can you expand on that?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Well, let’s take something fun, easy, and small, humor, and then let’s take something profound, and difficult, and big, mystical experience. They’re similar. They both help you to transcend yourself. When you’re laughing, you’re not thinking about yourself. You’re making a fool of yourself. Your body is shaking like a jelly. And you’re not uttering rational words. You’re just giggling.

The thing is really funny. Humor is a way of getting out of yourself, transcending your egotism. And if you don’t have a sense of humor, if you’re taking yourself terribly seriously, that’s very dangerous. I think of all the creatures God created, the one with the least sense of humor is the devil.

AUDIENCE: Thank you very much. On to the next one. We have, what is the place of leisure for philosophy, and how do you think that should be inserted into college life?

DR. PETER KREEFT: That’s a very good question. The obvious answer to that is to read a little delightful philosophical classic by Josef Pieper, entitled Leisure, the Basis of Culture. Leisure is not just sitting back and doing nothing. Leisure is also not something only the rich or the upper classes can have, or something that society gives some people and not others. Leisure is a choice.

Leisure is your choice to overcome the pragmatic and utilitarian assumption that everything has to have a rational justification in something else. There’s got to be a reason for doing something. You can’t just be silent and think and wonder. Well, if you don’t, then you can’t be a philosopher, because philosophy begins in wonder.

Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle all say that philosophy begins in wonder. And wonder doesn’t happen when you’re, well, let’s say, I take that back. I was going to say wonder doesn’t happen when you’re scrubbing the floor or changing a baby’s diapers. It can.

But even then, you have to have an interior leisure, a place where your mind can freely roam and just look at the truth and look at the darkness and not make demand. We love to sit in a darkened movie theater and simply be entertained by images on the screen. But when we do studying, we do it in a kind of a technological way. Here’s how I’m going to get an A. I’ve got to study this now. And here are the bullet points that I’ve got to memorize. Nothing wrong with doing that, but that’s not wisdom. That’s not the way to wisdom.

The higher a thing is, the more spiritual thing is, the less of a technology I have for it. How do you love? Is there an art of loving? Erich Fromm wrote a book by that. It’s a totally bad book, but it’s a totally bad title. There’s no art of loving. You just do it. How do you become a saint? Is there a button pushing method? Is there a spiritual technology? No, there isn’t. You just choose to do it.

So how do you just free your mind from work, from the means and end relationship so that you have to do this in order to attain that? You just do it. You just contemplate. You just look. When you go to a museum or a concert, you think, how am I going to use this? Can it make me some money? Can it make me more famous? Will it give me an A on the test? And you’re not even doing it.

Well, there’s two ways of philosophizing. You can philosophize as a job, as a task, or you can philosophize as a contemplative experience. And that’s not just about philosophy. That’s about even higher things. One of the best descriptions of being a saint, which is the meaning of life, I heard from St. John Vianney, who observed a peasant spending hours in church praying, and he knew he had a deep habit of prayer, and he asked him what he did when he prayed. And the peasant said, “Well, I just look at him and he just looks at me.” That’s leisure, and that’s the basis of spiritual culture and religious culture.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. The next question is, if today we live in an era of post-modernism, what can we expect to come next?

DR. PETER KREEFT: I don’t know, and I don’t care. I don’t have a crystal ball, and God gives us the present moment and doesn’t give us the future. And we’re really dumb about the future. Almost all predictions become wrong. God gave us a lot of knowledge about what we’re supposed to be doing right now. We know darn well what we’re supposed to be doing.

We’re supposed to be doing what Jesus Christ is doing, giving our whole heart to God and our neighbor. That’s very clear. What will come of it? We don’t know. That’s in God’s hands. Let the chips fall where they may. You don’t know the future. That’s what’s wrong with utilitarianism, which is the most popular ethical philosophy in America.

Utilitarianism says that the good is whatever you can predict will cause the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. But you can’t predict that. That’s saying, God, live in the present, because you have to, whether you want to or not. You can try to escape the present, try to live in the past, you can try to live in the future, but it won’t work.

Because all those attempts to forget the present and live in the past, or to forget the present and live in the future, are attempts that are made in the present. So just do God’s will right now. What Brother Lawrence calls the sacrament of the present moment. Be a saint right now. Give your whole self to God and your neighbor right now.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. That was a wonderful answer.

AUDIENCE: The other question that we have is, the title of this talk, is college making us wiser?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Yeah, I was afraid to ask that. I’m not prepared to answer that question. Maybe it’s because I’m old and curmudgeonly. So if I have to answer that question, honestly, I will give an answer that I am not at all confident of. The answer is no. The answer is, my students are getting stupider and stupider. Not their fault, they’re intelligent, but the humanities are in drastic decline.

And the ability to read, and the ability to think, and the ability to imagine and appreciate, it seems to me, is radically declining. And the more digital technology takes over, and the more all our courses become technologized and quantified, and the more we sink with our souls into our cell phones, I think the worse that will be. So we have to protest. We have to look for positive alternatives.

Human nature doesn’t fundamentally change. We’ve still got the equipment. We can misuse it, but then we can turn around and use it right again. This is why a lot of these little classical colleges are springing up all over America in protest against big universities. They’re going down. They’re going up. It’s a kind of a spiritual capitalism, but that’s product self.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. The next question is, philosophy doesn’t seem to solve the pragmatic issues of our time. Why is it worth giving it our time?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Either because the pragmatic issues of our time are not terribly important, like how can we increase the GNP, or because the truly pragmatic issues of our time are indeed dealt with by philosophy. Take the fundamental problem of economics. What is economics? Economics is fundamentally the science of profit and loss. All right. I would like to quote a sentence from my favorite economist.

I think this is one of the most practical sentences ever written. What does it profit a man if he gained the whole world, but loses his own soul? Philosophy can turn into things like that.

AUDIENCE: That is a great one. The next one that we have is, what books or philosophers discuss happiness in this life, and how do we explore this topic while recognizing the priority of eternal happiness?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Well, I gave you 10 answers to the first question. Every one of these philosophers deals with what Aristotle called happiness, not just as a psychological feeling, but as a true human flourishing, a success, a way of avoiding getting A’s in all your subjects but flunking life. What was the second question besides what philosophers?

AUDIENCE: The second part is, how do we explore this topic while recognizing the priority of eternal happiness?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Well, you have already made the first great discovery, namely that eternal happiness is more important than temporal happiness. You will find that throughout the Bible and throughout the lives of the saints, you find two things. You find the two acts of the human drama.

On the one hand, there are problems, there are challenges. God lets bad things happen to good people. The second part is that he delivers it from them. On the one hand, he deliberately allows bad things, even morally bad things, much less physically bad things, into our lives. Know that. Why? Why does he do that? He loves us, because he knows that after we are delivered from them, we have more happiness at the end than if they hadn’t happened.

Thus, to go so far as to call the fall in the Garden of Eden a happy fall, a fortunate fall, because it brought about so great a redemption.

AUDIENCE: Great, thank you. The next question is, since we have no record of Socrates other than that Plato derives from his teachings, why do we not assume that Socrates is the greatest of the philosophers?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Well, we do have other recollections of Socrates. They’re not nearly as important as Plato’s, but it doesn’t much matter how much of Plato’s Socrates is fictional and how much is factual. Both scholars put the difference between book one of the Republic and the rest of the Republic, because in the early dialogues and in the first part of the Republic, Socrates is very lively, and he has people who disagree with him, and it’s not about politics, it’s about the meaning of individual life. And then Plato goes off into politics, and Socrates’ figure becomes a little more of a trick figure. He sounds a little bit more like a university professor who has a lot of answers and has a lot of lecturing.

But there’s a Socrates in all of us. It’s not that Socrates is this weird figure that I’m asking you to imitate, it’s that Socrates exemplifies a natural curiosity. The love of wisdom is a human thing, not an artificial thing. It’s not like skydiving, which may be delightful, but it’s not essential to human nature, but philosophy is.

So just tap into your inner Socrates, and as an aid to that, read Plato’s Socratic Dialogues.

AUDIENCE: Awesome, thank you. Next question we have is, I have been reading St. Thomas Aquinas by G.K. Chesterton. However, I find it difficult to understand. Should I start reading the Summa Theologiae, or what autobiographical book can you recommend to start with?

DR. PETER KREEFT: According to the three greatest poets of the 20th century, including Gilson, Maritain, and I think it was Joseph Owens, that book by Chesterton is the greatest book that any human being has ever written about Thomas Aquinas. It’s funny. It does what Emily Dickinson tells you to do as a writer. Tell the truth, but tell it slant. A lot of slant in Chesterton, a lot of slyness, a lot of apparent silliness, which is really deep stuff. It’s not a code that you have to break, not a puzzle that you have to figure out, but you have to be open to humor and indirection, and especially the use of strange images. But give it, give it a try. There’s nothing better.

AUDIENCE: The next question is, who is your favorite thinker alive today to read?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Oh dear. I was afraid you’d ask that. Ah, all the dead ones are dead. Huh. Writer to read, huh. Well, I’m going to give you a very, very strange answer. An answer that I didn’t know I was going to come up with. Pope Francis. I don’t think Pope Francis is very bright. He’s not a great philosopher or theologian. I don’t think he’s a good politician. I think he’s very naive and making some serious mistakes with the Chinese, but he’s the Pope, and he’s the Holy Spirit’s instrument for the church, and he’s a holy man, and he has a true heart for the poor and for all of us, and because he is Saint Peter’s successor, listen to him.

If I were one of Jesus’ disciples, or were able to hang around there, I would be most interested in Saint John. He’s brilliant. He’s a great poet. He’s a profound theologian. Peter, on the other hand, is a simple fisherman, and he makes a lot of mistakes. I mean, Peter has foot and mouth disease. He’s always saying the wrong thing, and Jesus chose Peter to lead the Apostolic College, so listen to Peter’s successor.

AUDIENCE: Awesome. Thank you. Next question I have is, in your own life, who has been the most influential philosopher?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Well, I guess the most obvious answer is to pick one of the ten that I’ve just mentioned, but instead I’ll pick some living philosophers that have influenced me. The first philosopher that influenced me was the one that I had at Calvin College, and he was William Harry Jellema. He was probably the best teacher I ever had, and there are dozens of people today who are philosophers because of his teaching.

Then at Yale, I had the most brilliant mind I have ever met, Brand Blanshard. He was an atheist, but a very rational and utterly fair theist. Absolutely brilliant. And then at Fordham University, I had Father Norris Clarke, who I think is the best Thomist of modern times. He’s a kind of a living Thomas. He thinks like Thomas, humble, clear. The clearest book on the most difficult aspect of Thomas is Metaphysics. I’ve read dozens and dozens of books about that subject. It’s one by Father Norris Clarke, but one of the many.

And finally, one more. At Fordham, I also had Dietrich von Hildebrand, a very profound German philosopher. But Hildebrand is a deeply Christian phenomenologist, not easy to read. No Germans are easy to read, but very worth reading. I never met von Hildebrand, but I had his disciple.

I’ve been very lucky in having good teachers. And if you ask me now, well, give me the name of one other person who’s not dead, and who’s alive, and who’s writing you love the most. I’ll give you two. A fiction writer and a non-fiction writer. The fiction writer is Michael O’Brien, a Catholic novelist in Canada, I think. And the non-fiction writer that I enjoy reading the most, I think, is Anthony Esolen. Tough, commonsensical, always sound and useful.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. The next question we have is, what book would you recommend to an atheist who is beginning to open their mind to the idea of a God?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Well, I wrote a book called Letters to an Atheist, exactly for him.

AUDIENCE: Perfect. The next question is, it seems modern critiques on many ancient philosophies and proofs, namely those for God’s existence, are just terrible yet so effective at convincing people. What would you say on that?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Do your homework. Read the originals. Even a thinker as brilliant as Bertrand Russell can make elementary mistakes. He argues, for instance, that Thomas Aquinas’s argument for God’s existence contradict themselves because they begin with the premise that everything needs a cause, and thus deduces that there must be a first cause. If everything needs a cause, then God needs a cause too. So, he’s not a first cause. The answer to that is he hasn’t done his homework.

Aquinas never says that everything needs a cause, that every change needs a cause, every event needs a cause. God is not a change or an event. So, go back to the originals. If modern philosophers are commenting on pre-modern philosophers, don’t read the pre-modern through the eyes of the moderns, but vice versa. Don’t read the text by assuming the comments.

AUDIENCE: Awesome. Thank you. The next question we have is, how has philosophy helped you develop your own faith?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Well, for one thing, it has shown me that the faith is reasonable. And reason is not just a power, not even a kind of a veto power. Reason is something so essential to us that we use it everywhere. It’s like eyesight. It enables you to see things. And if somebody shows you a lot of other things, you see more. And that somebody is God, and those other things are the things known by faith. But even faith has to be understood by reason.

So, it’s not as if faith is over here and reason is over there, but in a sense, faith is a kind of reason. And it’s the most certain kind, because God alone can’t make mistakes. Faith can. We want to know what’s true, what’s real. And our intelligence tells us much of that, and our cleverness tells us much of that, and our common sense tells us much of that, and our conscience tells us much of that. But when God tells us that, we know that that’s infallible, and none of the other things are. In other words, faith and reason are both ways of knowing the truth. They’re both kinds of light.

AUDIENCE: Great, thank you. And this is the final question. It says, I’m a college student. What can I do, practically speaking, to get other students excited to learn about philosophy?

DR. PETER KREEFT: Talk about it. Share your mind and your heart. No gimmick, no technique. Don’t come to a conversation, prepare for battle. Just do what friends do. You found something great, you share it. Hey, you’ll like this too. Try it, you’ll like it.

AUDIENCE: Awesome. Well, that’s all the time that we have for questions. Thank you again, Dr. Kreeft, for your contribution to the Newman Lecture Series, and for your years of work educating us on the topics of philosophy and religion.

DR. PETER KREEFT: Well, thank you for the opportunity, and I thank you for the very good questions. And God bless you all.

Related Posts

- The Dark Subcultures of Online Politics – Joshua Citarella on Modern Wisdom (Transcript)

- Jeffrey Sachs: Trump’s Distorted Version of the Monroe Doctrine (Transcript)

- Robin Day Speaks With Svetlana Alliluyeva – 1969 BBC Interview (Transcript)

- Grade Inflation: Why an “A” Today Means Less Than It Did 20 Years Ago

- Why Is Knowledge Getting So Expensive? – Jeffrey Edmunds (Transcript)