Read the full transcript of geopolitical consultant Kishore Mahbubani’s lecture titled “What Happens When China Becomes Number One?” at Institute of Politics Harvard Kennedy School on Wednesday, April 08, 2015 – 06:00PM.

Listen to the audio version here:

TRANSCRIPT:

DAVID ELLWOOD: Good evening, everyone. My name is David Ellwood, and I want to welcome you here to the John F. Kennedy Junior Forum at the Harvard Kennedy School. This is a special occasion for a number of reasons. The first is that this is the Albert H. Gordon Lecture, which was established in 1987 through a gift from Mr. Gordon, who received his undergraduate degree from Harvard in 1923 and his MBA in 1925. The lecture focuses on the fields of finance and public policy, with special attention to internationalization, and the terms of the lecture specify the speakers should generally be chosen from outside the Harvard community. Well, I think Singapore is a bit of a distance, although this is someone who’s very much been a part of our community in so many different ways.

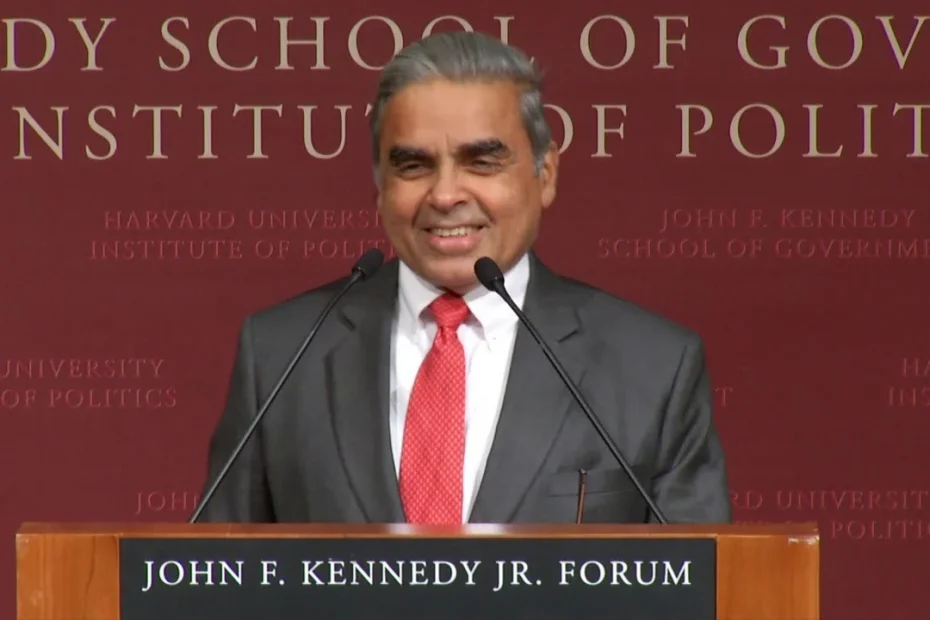

I will definitely say that our speaker is a remarkable man. Kishore Mahbubani’s career in public service spans government, academia, and exemplifies the commitment of advancing the greater good and spirit of innovation that we here strive for. He graduated with first class honors with a degree in philosophy from the University of Singapore. He then went to Dalhousie University in Canada where he received a master’s in philosophy and an honorary doctorate. He’s also spent a year here as a fellow at the Center for International Affairs at Harvard University.

His first part of his career was with the Singapore Foreign Service where he served between 1971 to 2004. He’s had postings in Cambodia, and he actually served during the war in Cambodia there, 1973 to 1974.

Now I think I know a thing or two about what it means to be a dean in a school with a name of an iconic public figure of whom the nation is proud. And I certainly have been enormously honored to be here at the Kennedy School. Kishore took over the school in the name of a living legend. And talk about high expectations. Lee Kuan Yew was a remarkable leader and was vigorous and engaged throughout his life.

He was one who believed very deeply in the power of education and the notion of a strong, merit-based, highly accountable government with essentially no corruption to be tolerated at any cost. And Kishore took over that role of running a school with a living legend. And honestly, the Kennedy School has enjoyed a very close relationship with the Lee Kuan Yew School for many years, including through the Lee Kuan Yew Fellows program in which mid-career students in public management from the LKY School spend a semester here as residents. We’ve benefited immeasurably from that association as well as learned so many lessons from watching Singapore emerge as a remarkable nation at a remarkable time. And I too have had this enormous pleasure of getting to know Kishore.

I remember the first time I met him was in Davos. And, again, we had just both become deans. I think we were both a little concerned—I was, I’ll just be straight, I was scared. And here’s this guy, and so we sort of compared what we’ve done before. And, you know, so I’m meeting this guy who’s, “Oh, well, I was president of Security Council, ambassador to UN, various things and so forth.” I say, “Well, I studied poverty.” But a great friendship was born. And throughout the years, we’ve spent a great deal of time together.

Obviously, Lee Kuan Yew, the remarkable leader of Singapore, passed away very recently at the age of 92, and we certainly share the grief of all the people in Singapore. And what a remarkable man he was.

I would also just say that one of the things I comforted myself when we were meeting in that first time in Davos was, “Well, okay. But, you know, I’m going to be the dean of the Kennedy School and so forth, and we’ll just see what he does after he becomes dean.” Well, what he just did was write book after book after book that was on the bestseller list, that was talked about, argued about. These include “The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World,” a series of books including “Can Asians Think?”

And constantly, he has pushed and challenged us to think about what a world will look like when the center of gravity shifts from the United States and the West to the East. And indeed, now there’s all kinds of talk about what’s next for Singapore in his forthcoming book, “Can Singapore Survive?” It is no surprise that this man who’s done so many remarkable things both in running an institution and in his writings was listed by the British current affairs magazine Prospect as one of the top fifty world thinkers in 2014, and he’s won so many different awards, I cannot mention them all. But I think the simplest way to frame this is to indeed say, Kishore is by far the best way to answer the question posed provocatively in your book, “Can Asians Think?” So with no further ado, Kishore Mahbubani.

Kishore Mahbubani’s Lecture

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Thank you, David. The trouble with having such a generous introduction like that is that after that everything is downhill. The best I can do is sit down and keep quiet. But anyway, it’s a great pleasure and delight to be here. And I’m really glad you highlighted the very special relationship, David, that our two schools have.

And indeed, frankly, the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, which began in 2004, has been successful because it inherited a public policy program that was set up by the Harvard Kennedy School in Singapore in 1991, I believe. So we’ve inherited a lot from the wisdom and advice from the Harvard Kennedy School. I want to thank you very much for that. I also want to thank you for mentioning Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, who passed away. I think I’m not giving a big secret away if I say that he was a great fan of Harvard.

And he really treasured the relationship that the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy had established with the Harvard Kennedy School, and he strongly encouraged me to keep it up. And I think he’d be very happy to see that the Lee Kuan Yew School is being recognized here again at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Now let me try to begin my remarks in twenty-five minutes to answer the question. I do have actually quite a long text but I would not think we could put up on your website of the Harvard Kennedy School and on my website too. What I’ll give you is a kind of a summary of the lecture.

Three Financial Stories

But let me start at the beginning by saying that, you know, in America, I know you begin with a joke. Unfortunately, we Asians, we don’t have jokes. I think the title of my next book would be “Can Asians Joke?” But I’m going to steal, frankly, literally a joke that was told by one of my predecessors in this Albert Gordon series. His name is Richard Fisher.

And this is how he began his lecture when he gave this Gordon lecture in 2009. He said, quote, “Yesterday morning as I got on the plane to fly up here, I turned to Nancy (his wife Nancy) and said, ‘In your wildest dreams, do you ever envision me following in the footsteps of Mikhail Gorbachev, George H.W. Bush, David Rockefeller, and Ban Ki-moon in giving the Gordon lecture at the Kennedy School?’ And Nancy replied, ‘I hate to let you down, Richard, but after thirty-five years of marriage, you rarely appear in my wildest dreams.'” I think my wife if she were here would say exactly the same thing.

So, anyway, to begin in the spirit of the Gordon lecture who said we should talk about development in the financial sphere, the way I’m going to deliver my remarks is that I’m going to first tell you three stories from the financial sector and then later at the conclusion I’ll explain to you why these three stories are important.

And in terms of explaining and trying to answer the question, I’ll first try to answer the question, of course, what are China’s goals and aspirations as it tries to emerge and rise? Secondly, how is the relationship between United States and China played a role in influencing the rise of China? And finally, try to make the point—which is I guess the critical point I’m going to make at the very end—that how China behaves as number one will be very strongly influenced by how America behaves. That’s number one. And that’s why these three stories are important and this is why I’ll begin with them.

# Story One: The Global Financial Crisis

The first story is about an event that happened at the height of the global financial crisis in 2008-2009. And until that financial crisis came about, the Chinese were very happy that they had developed an interdependent relationship with the United States of America. So that while China relied on America to sell its exports and to buy its products, America in turn relied on China to buy US treasury bills and to make sure that the US could continue to sell these treasury bills overseas. So they both felt that as Tom Friedman said in one of his columns, that they were joined at the hip in a mutually interdependent relationship.

And indeed, I can tell you this, as a matter of fact, at the height of the crisis, when things looked really bad, the Bush administration actually sent an envoy to Beijing in 2008 and said please continue buying US treasury bills because that’s what we need to preserve global financial stability. And the Chinese were happy to do so, and I suspect the Chinese even felt a bit smug. See, Americans depend on us.

But then lo and behold, about a month later, in a move that completely shocked the Chinese, the US Fed announced the first round of QE measures in November 2008. And as you know, with the QE measures, essentially, the US could print money to buy US treasury bills. And lo and behold, the Chinese said, what’s happened to this interdependence? The Americans can just turn on the printing press and take away this dependence on China.

And indeed, one commentator at Axel Merck said, “The US is no longer focusing on the quality of its treasuries. In the past, Washington sought to promote a strong dollar through sound fiscal management. Today, however, policymakers are simply printing greenbacks.” And Merck said that by relying on the Federal Reserve’s printing press, the US has effectively told other nations, “It’s our dollar, but it’s your problem.” So that’s one story about the financial relationship between US and China.

# Story Two: Extraterritorial Application of US Laws

Let me mention a second story from the financial world, which I think not many people notice. Now I think you must have heard that the United States has been prosecuting several foreign banks, including HSBC, RBS, UBS, Credit Suisse, and Standard Chartered. Now for example, Standard Chartered Bank was fined three hundred and forty million dollars for making payments to Iran.

And most Americans reacted with equanimity to this fine paid by Standard Chartered Bank and thought that the bank was just being fined for dealing with the evil Iranian regime. However, few Americans actually noticed that Standard Chartered Bank, which was domiciled in the UK, had broken no British laws and had not violated any UN Security Council sanctions. But because the payments made through the Standard Chartered System went through the New York clearing system, the US dollars entered the territory of US laws, and so Standard Chartered Bank was fined. And this is what is called, by the way, extraterritorial application of domestic laws. Again, remember this story when I come to the conclusion.

# Story Three: The SWIFT System

And the third story is about the SWIFT system, S-W-I-F-T. I think many of you may know what it is. It’s a system for clearing payments between countries. I think it’s centered in Brussels. And when things got very rough between United States and Russia recently, as you know, the United States said that it might consider denying access to Russia to the SWIFT system.

And in a column by Fareed Zakaria, one of our mutual friends, a graduate of Harvard, he described the Russian reaction to the possibility of being denied access to the SWIFT system. And interestingly enough, you know, most of us, when you look at Russia, we think Putin is the bad guy, Medvedev is a nice guy, good guy. But it was also the good guy, Medvedev, who said the Russian response to any denial of access to SWIFT will know no limits. So clearly, again, this was a global system for clearing payments and the United States was trying to use it for bilateral relations in terms of punishing Russia.

Now these are the three stories I’m telling you at the beginning and I’m going to conclude with these stories at the end.

China’s Goals and Aspirations

Now first of all, let me now answer the three questions that I mentioned earlier. First, what are China’s goals and aspirations as it emerges as number one? And here, the most obvious point that I need to make and emphasize at the outset is that even though China, as you know, is still run by the Chinese Communist Party, I can assure you one thing. The Chinese leaders, unlike Stalin or Lenin or Khrushchev, have no desire to prove the superiority of the communist system.

In fact, as you know, Khushchev famously said in November 1956, “Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you.” Now the Chinese don’t have the kind of aspirations that the Russians have to in any way prove the superiority of the communist ideology. So if it’s not communism that they’re trying to promote, what is it they’re trying to promote? And the simple answer is that they would just like to revive Chinese civilization.

Indeed, if there’s one thing that motivates the Chinese leaders, it is their memory of the many humiliations that China has suffered for over a century. As you know, from 1842, the Opium War to roughly 1949 or you can even go beyond that. And the one thing that drives the Chinese is a simple credo which says, no more humiliation for China. That’s the great motivation. And indeed, Xi Jinping, when he spoke to UNESCO in March 2014, this is what he said are the goals of the Chinese people.

He said: “The Chinese people are striving to fulfill the Chinese dream of the great renewal of the Chinese nation. The Chinese dream is about the prosperity of the country, the rejuvenation of the nation, and the happiness of the people. It reflects both the ideal of the Chinese people today and our time-honored tradition to seek constant progress. The Chinese dream will be realized through balanced development and mutual reinforcement of material and cultural progress. Without the continuation and development of civilization or the promotion and prosperity of culture, the Chinese dream will not come true.”

And I think in those few sentences, he brilliantly captured what is the heart of the aspirations of the Chinese people. To move away from an era of having been humiliated for a long time to an era where they once again feel proud about Chinese civilization and what it can accomplish. And indeed, if the CCP, the Chinese Communist Party could change its name to CCP, the Chinese Civilization Party, then I think it’d be a more accurate description of the goals and aspirations of the CCP. But, of course, while this may be the motivations, many in the west continue to believe that China’s approach is flawed because it is not changing its political system. And, you know, you can read in whatever Wall Street Journal, New York Times, The Economist, there’s this constant belief that the best thing that can happen to China is to have a collapse of the Chinese Communist Party and have a democratic system.

The Paradox of Chinese Democracy

The one slightly provocative point I’m going to make here is be careful what you wish for. Because if the Chinese political system becomes more democratic, it could very well become far more nationalist and far more aggressive as a power. And the great paradox here is that the Chinese Communist Party is actually delivering a global public good by restraining Chinese nationalism. And if you didn’t have a strong Chinese Communist Party in charge, you might actually get a more nationalist, a more assertive China. So I believe that it’s actually in global interest to allow the Chinese Communist Party to evolve and change in its own way. And that way, I think we will have China that focuses on economic growth and focuses on strengthening its civilization.

US-China Relations

Let me now turn to the second question I said I will discuss, which is US-China relations because clearly, the relationship between the world’s number one power, which today is United States and the world’s number one emerging power, China is a key dynamic. And here, it is actually remarkable how stable the US-China relationship is. You know, in theory, when the world’s number one emerging power is about to surpass the world’s number one power, and as you know in PPP terms, China did surpass the United States in 2014. You should be seeing naturally, logically, and I think Steve Wall might agree, rising levels of tension between US and China. But instead, quite remarkably, we’re seeing a very stable and indeed a calm relationship.

And of course, the question is why. And here, I think we have to give a lot of tribute to the United States for having managed very well the relationship with China. Indeed, the United States has been remarkably benign over the years towards China starting from the days of 1990s. I mean, of course, starting from the Cold War and Kissinger’s trip and America’s efforts to bring China on board in the Cold War alliance against the Soviet Union and then opening up the American market, as I mentioned earlier, to Chinese products. And even after the Tiananmen episode of 1989 when relations between US and China could have taken a nosedive, US-China relations continued on an even keel.

Actually, I remember vividly in 1992 listening to the election speeches of Bill Clinton when he said famously in his campaign, “I will not coddle the butchers of Beijing if I become president of America.” And when he became president, we could have very well seen a sharp nosedive in the relations between US and China. Instead, to my surprise and I actually saw this with my own eyes, in November 1993 at the first APAC leaders meeting which was held in Lake Island of Seattle. That’s the first time that Bill Clinton and Jiang Zemin met face to face. And I could see that Jiang Zemin was incredibly uncomfortable, tense, and nervous and trying to figure out what the US president would do to him in this small close meeting where I was present. And to Jiang Zemin’s surprise and to my surprise, Bill Clinton coddled the butcher of Beijing.

And it was a very wise decision on his part. And by the end of the day, if you had watched the body language of Jiang Zemin and Bill Clinton, amazingly, they were almost good friends at the end of the day reflecting the great charm of Bill Clinton at the time. But this pattern has continued. United States has helped China by getting it into WTO. The United States has helped China by being sensitive on Taiwan, indeed coming down very hard on the leaders of Taiwan when they tried to push for independence of Taiwan.

So these are various ways in which the United States has demonstrated its wisdom and generosity towards the Chinese. And of course, speaking in Harvard University, I have to mention it is actually quite remarkable that the world’s number one power is training the elite of the world’s number one emerging power by allowing it to send two hundred and seventy-five thousand students to come and study in American universities. I think future historians will be wondering why was America so generous in supporting the rise of its number one emerging power. But all this has led to this geopolitical miracle that we have today where you have a stable relationship between US and China. And also, by the way, I also have to mention that Chinese themselves have been very careful and sensitive and from time to time actually bent over backwards to keep the relationship on an even keel.

I was just in Belgrade literally two weeks ago, and it’s the first time I’ve gone to a modern city and saw the results of bombing by NATO on skyscrapers. And, of course, Belgrade is significant. As you know, the Chinese embassy in Belgrade was bombed in 1999. Almost all Americans I speak to believe that it was obviously an accident, but hundred percent of the Chinese I’ve spoken to are convinced it was deliberate. But despite the fact of their belief that it’s deliberate, they swallowed the humiliation and said, our relations with the US are far too important.

We will swallow our humiliation this time and proceed. So both sides you can see have made an effort to keep the relationship on an even keel.

America’s Influence on China’s Future Role

So all this brings me to my third part. How American behavior and actions will have a significant influence on China’s role as a number one power. And here, I must confess to you in all honesty that even though I’m normally quite provocative in things I say, I feel a certain trepidation here in saying some of the things that I’m going to say in this section.

Because as you know, famously Bob Zellig many years ago called on China to emerge as a responsible stakeholder of the global system. But when he made that call, I think he assumed that, of course, the United States is a responsible stakeholder of the global system. And the hard part here is to try and tell the American audience that that’s not how the United States is often perceived overseas. And that’s why I told the three stories from the financial sector, at the beginning of my lecture because the rest of the world quite often sees the United States acting unilaterally, acting in its own interest and often at the expense of global interest. And David mentioned that I’ve been the ambassador to UN twice.

I was there. I’ve served there for almost ten years. And it’s rather tragic to watch in the UN as I did it firsthand to see that the institutions that were essentially created by the United States after World War II with the guidance of FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt and all that. These were basically American-inspired institutions which have then been undermined by American policies. And I think in many ways, the United States has been very unwise in undermining these global institutions because every action that the United States makes in undermining these global institutions could then be replicated by China.

And that’s why in my latest book, “The Great Convergence,” I decided to begin the book by quoting from a very wise speech that Bill Clinton gave in Yale in 2003. And this is what Bill Clinton said: “If you believe that maintaining power and control and absolute movement and absolute freedom of movement and sovereignty is important to your country’s future, there’s nothing inconsistent in that. The US is the biggest and most powerful country in the world now. We’ve got the juice, and we’re going to use it.”

But then he added a but. He said, “But if you believe we should be trying to create a world with rules and partnerships and habits of behavior that we would like to live in when we are no longer the military, political, economic superpower in the world, then you wouldn’t do that.” So Bill Clinton was being very wise in saying, you know, as long as America thinks it’ll be number one, yes, we can go on undermining multilateral institutions. But if we can conceive of a world in which we are number two, then surely it is in America’s interest to strengthen multilateral rules and processes. But what is strange is that Bill Clinton only gave the speech once and never repeated that again.

Because I’m told it’s political suicide in America to speak about America being number two. So most politicians tend to veer away from that possibility. But I think the time has come for the United States to think very hard about a world in which it might become number two and China might become number one, then surely America’s interests change dramatically. And that’s why if America wants to see a China emerge that plays by global multilateral rules and processes, the best way you can do so is not by giving speeches or saying eloquent words about how you should preserve the global system. The best way you do it is through your deeds.

And here, of course, I’m going to conclude by mentioning briefly the latest episode that has happened in US-China relations and which is, of course, as you know, is the Chinese decision to set up an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which unwisely the United States decided to oppose. And as you know, and this is in many ways a sign of the times, in the past, a veto by Washington DC would have meant that all the allies would have stood firmly behind the United States, and the United States veto would have held. But even to my surprise, the first country to break that veto was the number one ally of United States, which is the United Kingdom. And that’s a sign of the times that countries are now preparing for a world in which United States will no longer be number one. So we want to have that world to be a peaceful and orderly one.

The time has therefore come for the United States to ask a very simple question. Would the United States feel comfortable living in a world where China behaves just as America did when it was the sole superpower? Thank you.

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: Thank you, Kishore. So we now have time for questions.

As you all know, there are microphones in four locations, one here, one right there, one there, and one there. And the characteristics of a good question at the Kennedy School have three characteristics. One, you identify yourself. Second, it is short and has but one point. And third, it ends with a question mark.

So why don’t we start right over there?

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Good evening, sir. My name is Nico. I’m a mid-career student here at the Kennedy School. I’m also the cofounder of the Future Society at Kennedy School, which is a new student club.

And my question regards the role of China, the future role of China in the Middle East. We’ve seen the Middle East being the big area of tension for the past decades. And, I was surprised to see if I recall it properly that the first trip of the newly elected Egyptian president, Mohammad Morsi, at the time was to go to China, not to the US, which I saw personally as a big sign. And I was wondering whether you could share with us your perspective of how the region, the Middle East could change in this new era of Chinese rise. Thank you.

Middle East Policy

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: This is actually a very difficult question to answer. The tragedy about the Middle East is that it is the great exception in a world that, as I tried to demonstrate in “The Great Convergence,” is actually prospering and doing very well. Because that region is a great exception and, to be very candid with you, it has a very dysfunctional dynamic, it is a very difficult region to have any kind of long-term posture plans.

I am very confident that the Chinese want to see stability in the Middle East, but the Chinese will never try to play the role of the United States, which is to go in there and intervene directly and try to influence the political development either inside countries, as with the invasion of Iraq, or in the relations between countries. When the Chinese emerge as the dominant power, the one thing they will not try to do is to replicate American policies in the Middle East.

So next question is right over here. Do note there’s microphones here and here. And since I just go around, if you’re standing in line, head to one of the other microphones.

The Role of Millennials

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Hello. My name is Patrick. Thanks so much for this very thoughtful and inspiring talk. As a German, I try to be the diplomat between the U.S. and China. So my question is, how can millennials contribute to, as Kissinger would say, a peaceful coexistence between the US and China?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I think the millennials have an enormous contribution to make. And the first thing they should do is read my book, “The Great Convergence.” I’ll tell you, and it’s a serious point I’m making here. I mean, I’m selling my book, but I’m also making a very serious point.

The one key point that many people have not understood is that there are many respects in which the world has changed fundamentally. I use a simple boat metaphor to explain this change. In the past, when seven billion people lived in hundred and ninety-three separate countries, it was as though they were living in hundred and ninety-three separate boats with captains and crews taking care of each boat and rules to make sure the boats didn’t collide. That’s the old world order.

Now what’s happened is that the world has shrunk and it’s become small, dense, interdependent. So the seven billion people in the world no longer live in hundred and ninety-three separate boats. The seven billion people literally live in hundred ninety-three separate cabins on the same boat. But you only have captains and crews taking care of each cabin and no captain or crew taking care of the global boat as a whole. And that’s why you have global financial crisis. That’s why you have global warming. That’s why you have global terrorism. That’s why you have global pandemics happening also.

So I think my generation’s problem is that we’ve got so used to the idea that the only way you solve the problems in the world is by getting independent sovereign countries to talk to each other and resolve the problems. But the world has changed so much that our ideas about how to handle the world of tomorrow are still bound by seventeenth century Westphalian concepts.

So the millennials have to persuade the leaders of all the countries that the things that make us interdependent in the world are far greater than the things that divide us. And you’ve got to find a way of throwing away all the textbooks you use in the Harvard Kennedy School and write new textbooks.

China’s Universities and Global Influence

AUDIENCE QUESTION: I’m a mid-career MPA student here at the Kennedy School, and I’m a big fan of yours. I’m so glad to see you. My question is, I’ve been following your readings and Thomas Friedman and Fareed Zakaria, everybody talking about the post-American world. When you look at the world’s top twenty universities, not a single university is from China or at least top ten universities. There’s not one from China. Universities are not like stadiums that you are preparing for Olympic games. It takes you ten years to prepare stadiums. Look at institutions like Harvard or Yale. It has taken three hundred years to establish institutions like Harvard. How is China planning to fill that gap of universities? Because you so religiously talk about the power of higher education institutions. So how is China going to address that issue if it’s going to be the world number one power when not a single university from China ranks on the top ten universities in the world?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, since I see quite a few questions, if you don’t mind, I’m going to give very short, quick answers.

Firstly, I’m very pleased to inform you that I think about two, three weeks ago, the New York Institute for International Education, IIE, came out with a new book called “Asia as the Next Higher Education Superpower.” And the introductory essay was co-written by me and the fellow author, Thiamine, by the provost. Please read that essay because it actually gives you a lot of data to talk about trend lines.

Yes, it’s true that the largest, the best universities in the world are still in America. And so it’ll take some time, but the trend line is very powerful in terms of development of new universities, institutions of higher education and so forth.

But the second point, which is a very critical point that I need to make here is that America has been remarkably generous to the world by training the elites of the world in American universities. And I always say that one reason why East Asia has defied all conventional wisdom and why East Asia remains peaceful is that the elites in East Asia, including the Japanese, the Koreans, the Chinese, the Taiwanese, the Indonesians, the Thais, the Singaporeans, and Malaysians have all studied in American universities.

And you know what happens? They use the same concepts, they understand each other, and they can get along with each other. Now this is a remarkable contribution that American universities have made towards peace in East Asia that no one has fully recognized. So it’s in fact good for the world that America retains the best universities as long as it continues to train the best minds from the rest of the world in these universities.

The Future of Hong Kong and Taiwan

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Thank you very much. My name is Peter Wu. I’m a junior at Harvard College. My question is when China or if China becomes number one, what is the future for Hong Kong and the future for Taiwan?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I think both will do very well. For the simple reason that there is what I call a rising tide of prosperity in the region. Now they will have short-term political challenges. Hong Kong, unfortunately, never developed the art of managing and resolving political disputes. So it’s going through a painful learning phase. And in the same way, I think in Taiwan also you might have short-term political problems, but by and large, both will remain more or less as autonomous economic entities benefiting from the growth of the region.

And I want to emphasize since I come from Singapore and Singapore and Hong Kong are seen as competitors all the time, it is actually in Singapore’s national interest to see Hong Kong thrive and succeed because we need competition from another city state, and therefore, we can both do equally well.

Bridging Perception Gaps

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Hi. My name is Chi. Last name, Ji. I work for the internal think tank unit of a large American company. Thank you for presenting a view that, perhaps not to the sophisticated audience here at Kennedy School, but I think perhaps in the US in general, that is a little bit different. I follow non-Western, specifically Chinese press as well. And I think the point of view that you presented is quite normal from a non-Western press coverage point of view. But if we look at the average Western press and the public discourse here, and hence policy here, that point of view perhaps is odd. Just like you highlight with the Belgrade embassy bombing, we can actually have US and China looking at things from two totally different angles. So my question is, how do we bridge that public perception gap to then move toward more harmonious bilateral relations?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I mean, I must say that that’s a very difficult question. The thing is that as I get older, I get less and less surprised by things, that’s quite normal. But one thing that’s really surprised me is that on the one hand, the United States has clearly the freest media in the world, the best finance newspapers, the best finance television stations in the world.

But I can tell you this, as someone who travels to at least thirty, forty countries a year, when I come to the United States and I go to my hotel room in Charles Hotel and turn on the television, I feel that I’ve been cut off from the rest of the world. And literally, the insularity of the American discourse is actually frightening. And this is also true with the New York Times. This is true with the Washington Post. This is true with the Wall Street Journal. There is an incestuous self-referential discourse among these newspaper journalists and so on and so forth. And they reinforce each other’s perspectives and end up misunderstanding the world.

Because the one key point I emphasize is that the era of Western domination of world history was a two hundred year aberration. It’s coming to an end. And as a result of it, you’ve got to learn to understand non-Western perspectives in the world. And it’s actually quite frightening that in many ways, I find American intellectuals behind intellectuals including in Serbia where I just was or Greece or in Istanbul because they are much more aware of what’s happening in the world than most American intellectuals are. I don’t know how to solve that problem.

China’s Military Rise

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Thanks. My name is Ziyat Raza. I’m a mid-career MBA candidate here and also from Malaysia. So both Malaysia and Singapore and countries around East Asia have been benefiting greatly from the economic rise of China. We trade with China. We benefit from that. But there’s also the specter of security. China’s nine-dash claim on the South China Sea, some skirmishes along the way. And also, the increasing militarization of China is growing defense budget. So my question to you is, I think the entire world is looking to see whether China is true to its rhetoric of peaceful rise, but it’s particularly relevant for East Asia. We’re so nearby and we’re directly affected by this. So what are your thoughts on China’s rise as not just an economic power but also potentially a military power as well?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Again, very quickly. Number one, overall there’s no doubt that China has been rising peacefully. But for some strange reason, in the years 2010 to 2012 or 2013, China began to make serious mistakes in its foreign policy.

The one big mistake it made, for example, was when the Japanese arrested the captain of a Chinese fishing trawler. The Chinese put enormous pressure on Japan to release the captain and they succeeded. And then, foolishly, they asked Japan for an apology. And I told my Chinese friends, you already humiliated the Japanese by forcing them to release the captain of the Chinese fishing trawler. Why humiliate them further by asking for an apology?

Then as you know, they made mistakes in the South China Sea. In the ASEAN foreign ministers meeting in July 2012 in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, the ASEAN countries wanted to have the usual reference to South China Sea. China put pressure on Cambodia, the chairman, to block it. And then for the first time in forty-seven years, the ASEAN countries failed to produce their usual boring long joint communique because of Chinese pressure. So they made serious mistakes.

But what is astonishing to me is how quickly they learn from the mistakes. And I can tell you one of the most surprising things I did in 2014 was to be invited to Beijing by two separate Chinese think tanks in fully recorded conversation. And they only asked me one question: “Please tell me what mistakes has China made in its foreign policy.” I was stunned by that because I’ve never been invited to Washington DC to talk about mistakes in American foreign policy, but I get invited to Beijing. That’s a sign of the times that is how different the world is today.

So I think the Chinese themselves have not clearly made up what kind of power they want to be, and they are torn by contradictory impulses. And how we react to them, how we act as a role model for them will make a huge difference.

And here in the area of the military, I can tell you one key point I keep saying: it is now in America’s national interest to stop aggressive naval patrolling twelve miles off China shores because if you do that twenty years from now, there’ll be aggressive Chinese naval patrolling twelve miles off California shores. Let’s not push for that. Let’s work towards a new world where we no longer have to use the military. And I think at the end of the day, there will be no war between United States and China. Why not gradually de-escalate the military competition? I think it can be done.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Thank you. Thank you, David, and thank you, Kishore, for the great presentation. My name is Xing Chai Zhang. I’m from China.

Audience Q&A (continued)

AUDIENCE QUESTION: It’s a great honor to have this opportunity to ask questions. I’m the founder of My Lab Tea Company. My question is: you talk about Mr. Xi Jinping and his purpose to revive Chinese culture. What do you think is China’s core culture? How can Chinese core culture contribute to the world? And what can we learn from other civilizations through this process? Thank you very much.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I suspect there are many more experts in this room on Chinese culture and civilization. But I can tell you that there are obviously many roots of wisdom in traditional Chinese culture.

If you look back over the longer history of China over the past two thousand years or so, it’s actually surprising how few military adventures the Chinese had overseas. Within the Chinese Confucian ethos, the guy who’s a soldier is at the bottom of the value chain. So maybe developing an ethos in which the military is not so important is one possible thing that can emerge from Chinese culture and civilization.

But you’ll see things coming in many areas. For example, in the medical area, I think Chinese medicine will become more and more important. Just as Western medicine looks at the human body and tries to slice it up – looks at your kidney, your liver, your heart – the Chinese look at the whole system of the body. In that sense, as Chinese medicine rejuvenates itself, it’ll also make a development.

There are many other such places like this. Chinese poetry, Chinese painting, all that will come back in a much stronger way. One of the happiest things I look forward to in the next twenty years is that there will be not one but many major Asian cultural renaissance taking place in the world. And one of them will be from China.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Hi. My name is Tubin Kim. I’m a student at Harvard Law School. Thank you for coming to talk to us today. It was a great lecture. Some say AIIB is, in some sense, a stepping stone towards possibly undermining US dollar’s position as a reserve currency and preparing itself as the new reserve currency for the world or at least a competing alternative. I’m curious about your response to such arguments.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I don’t think the AIIB is a step towards replacing the US dollar as the global reserve currency. It’s actually the Chinese basically using the AIIB on one hand to find a use for the money that they have. On the other hand, there’s also a demand in Asia for more infrastructure. Even the ADB has estimated that Asia needs seven trillion dollars of infrastructure, and that’s what it’s using its money for.

But at the same time, I do agree with you that the Chinese have begun thinking about how long they can rely on the US dollar as the global reserve currency. Because traditionally, the reserve currency is always the reserve currency of the world’s number one economic power.

Now China is not yet in nominal terms the number one economic power. But within five years, ten years, depending on your guesswork and what the rates of growth will be, China will become the world’s number one economic power, let’s say within ten years. And then in that world, if you have a world in which China is the number one world economic power and the US dollar remains the global reserve currency, that will be a major global contradiction.

So it’s actually better for us now to find a solution to that global contradiction before it becomes a big problem because this will definitely be a big problem ten years from now.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: My name is Charles Dutta. I’m a student here at the Kennedy School. Arguably, in the era of US superpower, democracy could be argued as the main value that the US has been pushing around the world. How about when we imagine the day that China will be a superpower? What do you think will be the main agenda that will be pushed around the world?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Let me begin with the good news. They will not ask any country in the world to set up a communist party. I guarantee you that.

I actually believe in the long run, China itself will eventually become a democracy. The destination is not in doubt. It’s only the route and timing that you take. The Chinese learned so much from the collapse of the Soviet Communist Party because Soviet Union went overnight from a communist system to a democracy. The Russian economy imploded, became smaller than Belgium. Infant mortality rates went up, life expectancy came down, and the Chinese saw that and said, we don’t want to see that in China. So they will not make an immediate transition towards democracy. But in the long run, I think they’ll move in that direction.

But unlike the United States of America, the Chinese do not believe in proselytizing their beliefs. They do not believe that you have to copy or emulate them to succeed. And they also believe that it is far better for people to admire and respect them for their deeds rather than to pay attention to their words. So in a sense, we will have a very different world when the world’s number one power is no longer a missionary power in the world.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: From a technological institution down the river. My question is similar to the one that was just asked. I think your point is very well taken that you learn how to behave when you’re number one by looking at the person who’s now number one. We’re good to our parents so our children will take care of us in our old age. But how many years after China becomes number one do you think there would be real press freedom or artists would have freedom or the Dalai Lama could come to Tibet? How will that ever really happen with the communist dynasty that you praise, which you can only get away with in Cambridge, by the way?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: The question of freedom in China, I think, is a very critical question. I first went to China in 1980 and I arrived in Beijing. For a start, there were no skyscrapers. There were big roads. There were no cars, only bicycles. People at that time could not have the freedom to choose where to live, where to work, or what to wear – no kind of personal freedom.

Today, you go to China, the Chinese people can choose where to live, where to work, what to study, what to wear, where to go. When I first went to China in 1980, there wasn’t a single Chinese tourist leaving China. Last year, hundred million Chinese went overseas freely. And a hundred million Chinese returned to China freely. Now if there’s no freedom in China, if China was this despotic, oppressive state, would a hundred million Chinese come back to China? So clearly, there has been an explosion of personal freedoms in China on a scale that the Chinese people haven’t experienced.

You mentioned difficult things like the Dalai Lama. And I agree with you that China should deal with the Dalai Lama. But isn’t it shocking that the United States of America, which is the world’s freest society in many ways, actually prevented some Islamic scholars from coming to teach in American universities barely ten years ago? That’s shocking.

So all I can say to you is no country is perfect. Every country has got to learn to improve itself.

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: Kishore, I wanted to take advantage of my position here to ask you a question that no one else has seemed to ask, but since you asked it rhetorically yourself: after Lee Kuan Yew, can Singapore survive?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: My favorite answer is “buy the book.”

No, actually I did launch a book three weeks ago in Singapore called “Can Singapore Survive?” The answer I gave is very simple. The probability, of course, is that Singapore will survive. I mean, will not just survive, Singapore will do very well. Because Mr. Lee Kuan Yew and the founding leaders of Singapore created some of the strongest institutions in the world in some areas.

The quality of mind of the Singapore civil service, I think, is number one in the world. The quality of mind of the Singapore judiciary is also probably number one in the world. The quality of the Singapore military is probably among the top ten in the world. Singapore’s education system is already ranked among the top three or four in the world. We have the world’s best airport, the world’s best functioning port. So we have created a whole ecosystem of excellence in Singapore.

With that ecosystem of excellence, Singapore is poised to take advantage of a major historical opportunity that is coming its way because just as London served the European century and New York served the American century, the one city in all of Asia that is comfortable with all the major civilizations in Asia – with Chinese civilization, with Indian civilization, with Islamic civilization, and also Western civilization – is Singapore.

So Singapore is going to become the New York of the Asian century. So it’s a great time coming ahead for Singapore.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: My name is Yehabu Gamal. I’m a mid-carrier from the troubled area of the Middle East. My question to you is: do you have any doubt about China’s economic growth going forward? The rise to the number one is based on a wonder story of 8% growth year over year. Demographically, there are challenges. There’s a lot of challenges in the economy. Do you see the story really continuing to become the nominal number one in the world?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I’m really glad you raised that question because I’ve been here for forty-eight hours. And I must say almost every person I met in Harvard, the first question they ask me when we talk about China is, can China sustain its economic growth?

Of course, it’s possible that there could be a massive slowdown in China. They could grow at three, four percent or whatever. That’s possible. But if I was a betting man, I’m prepared to take bets with you all that I think China will be able to sustain growth of seven percent.

There’s a very good reason why the Chinese have decided to slow down their economic growth because they are now shifting from one model of economic growth to another. They used to rely a lot on export-led growth. They can no longer do that because there are no longer the big markets in the west that they can rely on. They’re trying to switch to internal consumption-led growth. It takes time to do that. And if you are running a fast train around a corner, it’s best to slow down and do that.

Secondly, look at the amount of investments that China has put in the infrastructure, the world-class infrastructure that China has built in their ports, airports, roads, rail and so on. That kind of world-class infrastructure reaps dividends. Plus, the Chinese Communist Party is in many ways one of the most meritocratic organizations in the world and the quality of mind of key Chinese policymakers has never been as good as it is today.

Now you have a government staffed by remarkably good minds taking advantage of a world-class infrastructure. I would say the possibility of maintaining good growth is there. And within Asia, China is big but even beyond the Chinese 1.3 billion people, in all of Asia there are 3.5-4 billion people. That market is becoming more integrated too, so they also benefit from the integration of that region.

So there are many other sources of growth apart from the export growth that they had in the past. So if I was a betting man, I would say they can sustain the seven percent growth.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Hi. My name is Jack Mulhern. I’m a former tour guide at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. It’s a great honor to have you here, first of all. I attended the law school about six months ago, and Tommy Coe, the US ambassador to Singapore, posited a theory that eleven times one country has always been on top, and they’ve always, in the history of humanity, been superseded by the country in number two. I’m just wondering if this is inevitable due to what I’ve noticed China is doing. They’re buying factories in Indiana that are producing rare earth elements that we need for our cell phones and our F-14 and F-16 fighter jets and so forth. And I’m not saying that they’re not benign. I’m just saying that this is what’s happening. So I’m wondering if it’s a bit of inevitability that the country who’s always number two supersedes the country that’s now economically number one.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Tommy Kho, by the way, is a Singapore investor, former Singapore investor to the US, a brilliant guy. In fact, I succeeded him as ambassador to the UN.

I mean, of course, it’s never inevitable that the number two will overtake number one.

China’s Path to Becoming Number One

As you know, Japan was supposed to overtake America, and Professor Ezra Vogel wrote the famous book saying “Japan is Number One,” but the Japanese never became number one. That happens from time to time, and it’s conceivable that China will not become number one. It’s conceivable. But the probability is very clear that if you have a country with a population of 1.3 billion people (China) and a country of 300 million people (United States), if the average Chinese can perform at 25% the level of the average American, China will have a bigger economy.

And if you have any doubts about the capacity of the Chinese mind to do well, look at the exam results of Chinese students in any leading American university. Look at the list of PhDs that come to collect, you see the success of the Chinese intellectuals.

What’s happening here is that Western education was developed for the Western mind. But one thing we haven’t noticed is that in the last ten years, when you take Western education and you combine it with the Asian mind, including the Chinese mind, it has an explosive effect.

So the Asians are thriving with Western education. And inevitably, this is going to fuel the rise of China in a big way. I’m very confident that the average Chinese can perform more than 25% the level of the average American. And that’s why I think China will have a bigger economy.

Final Questions

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Hello. My name is Mabo M. Weislav, a student at the Business School. Thank you for being here this evening. My question is: how would you characterize, in all likelihood, the US-China relations specifically in the range of 15 to 25 years where while China will likely be the number one, the US will likely be a close number two?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: It’s possible that the United States will be a close number two to China. But many of the projections that I’ve seen—for example, Goldman Sachs has projected that by 2050, the number one economy in the world will be China, and I’ve been speaking a lot about China. The number two economy in the world will be India, and the United States will be number three.

It’s actually surprising that so few Americans speak about that world. It’s already impossible to speak about being number two. It’s even harder to speak about being number three. But that frankly is also going to happen.

I wrote an essay recently in which I said that if you look at the most successful ethnic community in the United States, I would have thought in the past it would have been the Japanese or the Chinese or the Koreans or the Jews. But the most successful ethnic community in United States by far is the ethnic Indian community. And if you look at one statistic, if the average Indian in India can achieve half the per capita income of the average Indian in America, India’s GNP will not be $2 trillion but $25 trillion. And if you go to India as I do, the sense of optimism about the future is phenomenal.

So I’ve been talking a lot about China, China, China, but there’s actually another bigger Asian story. There’s also India and other states that are doing very well.

In that world of tomorrow, it is just by sheer mathematical logic. The amount of space that 300 million Americans have carved out for themselves politically, economically when they represent less than 5% of the world’s population has been phenomenal, has been exceptional. But it cannot carry on because the rest of the world has stopped underperforming.

And if they start performing normally, America will continue to remain a strong, dynamic, successful country, but its relative share of the global GNP can only shrink.

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: Kishore Mahbubani, thank you so much. I should say we’re going to have a reception here momentarily. So those of you who would like to stay and chat a bit more, Kishore has a flight, I think, has to leave here by 8:15, but at least be around for a little while for those of you who didn’t get a chance to question. Thanks again.

Related Posts

- Transcript: ‘Quite a Shock’ Trump and Mamdani ‘Bro Up’ in Oval Office – Piers Morgan Uncensored

- Transcript: Kamala on Marjorie Taylor Greene’s Rebellion – Bulwark Podcast

- Transcript: Hungary’s Viktor Orbán on Putin vs. Trump – MD MEETS Podcast #5

- John Mearsheimer: Bleak Future of Europe – Defeated & Broken (Transcript)

- Transcript: ‘Ukraine Is A Corrupt MESS’ Trump Finalizes Russia Peace Deal – Piers Morgan Uncensored