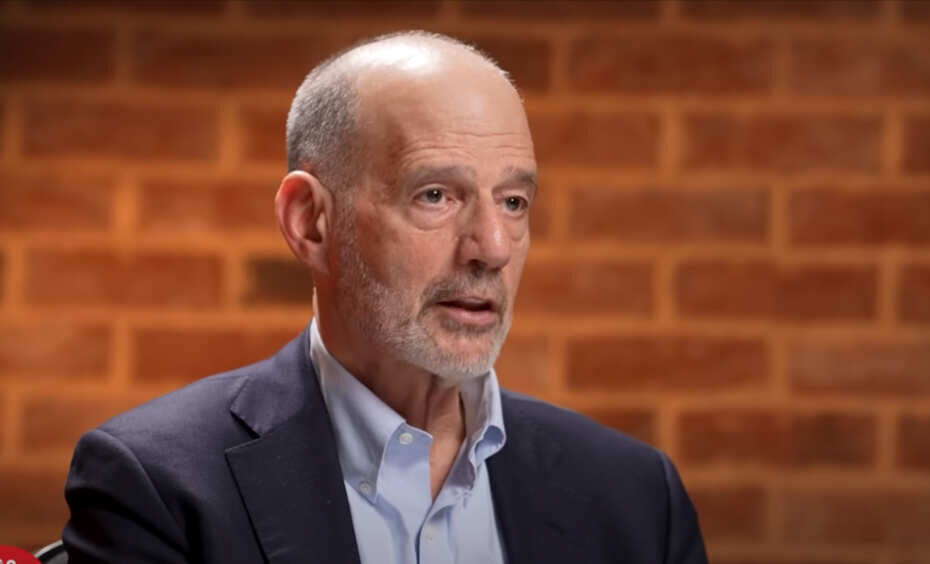

Read the full transcript of American historian specializing in ancient military history Barry Strauss’ interview on TRIGGERnometry podcast titled “Why Rome Collapsed”, May 28, 2025.

INTRODUCTION

INTERVIEWER: Barry Strauss, welcome back to TRIGGERnometry.

BARRY STRAUSS: Thank you. It’s great to be here.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, it is great to have you. We had you on about a year and a half ago. We talked about the great generals and military leaders. It wasn’t an interview that did huge numbers, but it’s genuinely probably one of our very absolute favorite interviews that we’ve ever done. And I hope more people go and watch it now that you’re on. But what we want to talk to you about today is Rome: the Decline and Fall.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: Before we do, we might want to tell people what Rome was, what was this great civilization, what were some of the key beliefs and values. And perhaps that will lead into why eventually, a decline and fall.

The Greatness of Rome

BARRY STRAUSS: Rome was a great empire. It stretched from Edinburgh all the way to Syria and Arabia, and for a short period all the way to the Persian Gulf. The Romans were some of the greatest soldiers in history. They were conquerors, they were tough guys. And they conquered this empire of about 50 million people.

They’re also extremely good at politics, at bargaining, at making friends, at using carrots and sticks. They’re ruling 50 million people. They’ve conquered them all. They only have 300,000 men in their army, which isn’t a huge army when you have an empire that stretches 3,000 miles and 50 million people. So they had lots of revolts, they were civilized.

Rome was originally a city state, very influenced by Greek culture. And the Roman ideal was an ideal of cultivated gentlemen who were public spirited, who were educated.

Citizenship was a major part of what made the Romans great when Rome was a republic. The fact that there was a core of citizens who all had military service, who all served the republic, who’d be called on to fight for the Republic. That was the basis of Roman greatness.

Also, Roman government was not a democracy. It was what the ancients called a mixed regime. The Romans referred to themselves as SPQR, Senatus Populusque Romanus. The Senate and the Roman people, they’re not just the Roman people, they’re the Senate and the Roman people. Senate is a word that we now have, the word senility. It means elders. The Senate is the council of elders.

INTERVIEWER: Quite appropriate, actually.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah. They didn’t consider themselves senile, of course, but these are supposed to be the wise men. They’ve served in a variety of public offices. Many of them have served in more than one. And they have huge authority in guiding the Roman state.

The people have assemblies, they’re politicians, there are elections. The elections are raucous, they’re wild. They’re a bit like our elections nowadays. And so with this political system which is very solid and very able to call on the responsibility and the loyalty of the people to fight for Rome, they also create this great army which is flexible, it’s orderly, ultimately becomes a professional army.

The Price of Success

Ultimately, Rome suffers from its success, pays the price of success. And conquering an empire turns out to be too big a burden for one small city state in central Italy to govern. Also, all this money pouring in, huge numbers of slaves pouring in, competing with free people, free labor, which can’t compete with it, huge turmoil.

The army goes from being a citizen militia to a professional army. And the soldiers go from being middle class farmers to being poor people. The Roman word for poor people is breeders. They’re mere breeders. Latin for that is proletarian. That’s where we get the word proletarian from.

Ultimately, these proletarians follow the strongest generals and you get people like Marius and Sulla and of course Caesar. And there’s a series of civil wars. And when the smoke clears, Rome becomes an empire, a monarchy. It’s no longer a republic. There’s still a Senate, there’s still citizens. There’s still a sense of loyalty to the center, loyalty to the emperors, even when they’re a bit wacky.

External Pressures and Internal Reforms

But in time, Rome faces more and more pressure from invaders from abroad, from both sides of the empire. In the west, various Germanic tribes. In the east, various Iranian regimes. First the Parthians one dynasty, and then the Sasanians another dynasty. The pressure grows greater and greater.

And the Roman Empire should have died in the year 260. That’s the year that the Roman Emperor is captured in battle by the Sasanian king. And the Sasanian king to humiliate the emperor uses him as a footstool to climb on his horse and he carves this in a big stone relief which you can still see in western Iran, this humiliation of the Roman Empire.

The Empire was in terrible trouble. There were plagues, there was inflation, there were assassinations, there were revolving door emperors. But a series of soldier emperors, strong men, rose to the occasion. They saved the empire by making it more authoritarian, by raising taxes, by taking away freedoms, by ultimately abolishing the power of the Senate, making it more centralized.

And finally, the one thing they did was they felt that the gods were no longer with them. The Romans were pagans, of course, like the Greeks, and they felt the gods are no longer with us. We either have to return to the old gods, bring back the old time religion, or try something new. And they tried a variety of things until they finally settled on one thing. Christianity.

Constantine is the first Christian emperor. And although he doesn’t require that everyone become Christian, he and his successors make it pretty clear that the way to success in the Roman Empire is to become a Christian. And people will convert, either out of sincere religious belief or because they think the God of the Christians must be right. Because after all, look how successful it’s been.

The Final Collapse

And so the Roman Empire is revamped, retooled, into the 300s AD with these new dynasties. But then trouble arises. The Germanic peoples in the west and in the north organize themselves. They group themselves into what one historian has called “supergroups.” Instead of being 50 different Germanic tribes, they’re now really only four different Germanic tribes. They learn the art of war from the Romans, they covet the Roman lands, they’re raiding the Roman lands.

That might have been the end of the problem. The Romans might have been able to handle that, except for a couple of things. One, the Huns arrive on the scene. Attila the Hun and his warriors from the steppes arrive on the scene and they are attacking the Germans in the various lands in which they live and driving them into the Roman Empire. And they find themselves forced to fight the Romans. And they’re very successful at defeating the Romans.

Nonetheless, the Romans still have strong armies and they still have terrific generals who might have recouped. But there are two other problems. We get a series of incompetent emperors. In fact, for 50 years in the 5th century, we’re now in the 400s AD, Rome is governed by these two incompetent emperors, two child emperors when they start out, boy emperors, and there’s rot at the top.

Second problem is that once these barbarians come and settle in the empire and Rome’s forced to let them settle in the Empire that they take away the tax base. If you don’t have the tax base, people aren’t paying taxes to Rome, but they’re paying taxes to the barbarian chieftains instead. You can’t have the professional army.

So now we turn to the old Roman way of doing things. We turn to the Roman citizens, but there aren’t any Roman citizens anymore. Citizenship. Of course, technically they’re Roman citizens, but the bond between the citizen and the state is gone. The loyalty of the citizens to the state is gone.

When Rome was rising, Rome and then all Italy supplied soldiers to conquer this empire. By the time we get to the 400s AD and well before that, there are no soldiers in Italy anymore. The Romans are becoming the Italians. They’re enjoying the good life. They’re not fighting. They use people from the outskirts of the empire and often Germans to do the fighting for them. So this is a ship that’s very hard to turn around. In fact, it turns out to be impossible to turn around. That’s the big picture.

The Roman Dictatorship System

INTERVIEWER: Well, that’s so interesting and it’s a breakdown, but we want to delve into it a little bit. One of the interesting things for me is, am I right, that the Romans had, even in the republic period that you could at times of war appoint people who were temporary dictators effectively, is that right?

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes. So the dictator is a temporary office. It’s a six month office. And when a dictator is appointed, it means that normal republican government stops and the dictator has supreme power for the period of war only. So it’s an office the Romans used.

There’s something like this in Britain in World War I when the Defense of the Realm Act was passed. And there was a sense that ordinary government business would have to be put on hold for the sake of the country or in the civil war in the United States when President Lincoln suspended habeas corpus and people said, “You can’t do that, you have no constitutional right to do that.” And his answer was, “I want the Republic to survive, so I’m going to have to do it.”

From Republic to Empire

INTERVIEWER: And how did the transition happen in terms of, you know, what was the culture and the history and the events that led up to the fact that this society which was a republic, became, you know, a monarchy or whatever you want to call it?

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah, well, I think in part, as I said, it’s the problem that success spoiled the Romans. They bring in so much wealth that you have people who now feel if I’m so wealthy and I’ve conquered kings abroad. Why don’t I get to be a king? You have series of generals like that.

You also have the problem of the poor, because another thing that the Romans get is they get slaves, massive numbers of slaves. And Roman Italy becomes one of the most egregious slave societies in history. This is a problem if you’re a poor free farmer because you can’t compete with this slave labor anymore.

And there are some very unscrupulous wealthy people who are snatching up the common land that’s needed for poor people to pasture their sheep and cattle and goats on, that disappears as well. And in some cases, they confiscate the farms of the ordinary people and the poor.

So you have huge extremes of wealth. Very, very wealthy people who have ambitions beyond those of their fathers and grandfathers. You have very poor people who are looking for some way to make a living. And you have all these slaves as well, who are skewing the economy. So these are the preconditions for a series of civil wars that they’re waged on and off for nearly a century until the end of the Republic comes.

Modern Parallels

INTERVIEWER: A lot of people listening to what you just listed might be thinking, that sounds a little bit familiar. I mean, we have in our societies extreme wealth inequality. We, you might say we have a slave class which is illegal. Often immigrants or new immigrants who are being paid in a way that means the local population can’t compete. We’re fat and wealthy. You’ve got these billionaires who are wealthy beyond the aspirations of any human in history, et cetera. Historians like to draw comparisons between what they see in the west today and the Roman Empire. Is there a legitimacy to that?

BARRY STRAUSS: Absolutely. I mean, I think one of…

INTERVIEWER: I was kind of hoping you’d say no, but…

BARRY STRAUSS: I’m sorry, I have to agree with you. One of the lessons of the Roman Empire is that societies with strong citizenship can weather the storm. And once that bond goes, they’re in deep, deep trouble.

So earlier on in the third century BC, when Hannibal invaded Roman Italy and inflicted some of the worst defeats in war that the Romans ever had. The Romans are able to bounce back because they have this strong citizenry. And they also have a series of alliances with people in Italy, especially in central Italy.

The Romans are very good at making deals, at saying, “One hand washes the other, you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” And they’re quite good at making ties with these allies.

One of the things that the Romans do. So the Romans come in and they conquer you and they say, “Who are the wealthy people in town? Who are the important, wealthy, influential people in town?” They say, “Look, you didn’t want to lose the war, but you lost. And we’re going to confiscate 10% of your land. But I’ll tell you what, if you behave, we’ll let your sons marry Roman women and their children can become Roman citizens. And we’ll let you, and people like you in your country will let you do business with Rome without paying any extra taxes. We’ll give you privileges.”

Romans are very clever at this. They’re very clever at co-opting people. So they build these bonds of loyalty that hold the empire together. But citizenship is the core of it.

INTERVIEWER: And isn’t the problem though is that you keep granting more and more people citizenship. You dilute the meaning of citizenship.

Roman Citizenship and Social Hierarchy

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes, they do, and that’s very insightful. So in the beginning of the third century, I think the year is 212, the Roman Empire emperor decides, you know, we’ve been giving citizenship, we’ve been doling out a little bit more, a little bit more over the years. Let’s cut to the chase and make everybody Roman citizens. And they’re all going to have to pay taxes now, but it’s diluted.

Now that everyone’s a Roman citizen, it loses its meaning. And in fact, the Romans come up with a new distinction. Because I want to have distinctions between the greater people and the lesser people. I’ll translate that as. And that replaces in a way the distinction between citizen and non citizen.

INTERVIEWER: And so the distinction between a citizen and noncitizen is what you get as a citizen. What do you get as a non citizen? Because also the problem comes, Barry, is that I imagine if there is no pathway for a non citizen to become a citizen, the problem is, is that you’re going to get resentment, anger, frustration, social instability.

BARRY STRAUSS: You do, you do. But the Romans are rather elitist people and they can’t imagine how you can have a society where everybody shares in the privileges. They think that it makes society more effective if you dole out the privileges little by little. And that’s how you get people to buy into the system and to work for you.

But an example of, answer your question, what do you get? So St. Paul, he’s in Judea, he gets in trouble with the authorities, they’re putting him on trial and he says, “civis Romanum sum,” I am a Roman Citizen, which he was, and that entitled him to a trial in Rome. So he goes to Rome. So it means you’re going to be treated better than someone who’s not a Roman citizen. If you’re punished, you can’t be whipped, you can’t be crucified. If you’re a Roman citizen, you have to get better treatment and you have certain tax privileges as well.

Corruption and the Fall of Rome

INTERVIEWER: And when we’re talking about the fall of the Roman Empire and we talked about many things, what about corruption? Because corruption seems to me the, as I’ve seen a society fall in Venezuela and corruption was the main reason why it fell.

BARRY STRAUSS: No society corruption’s not. I mean, you’re right, there was corruption in the Roman Empire, but corruption was endemic to ancient governments, as it’s probably endemic to all governments. There’s no reason to think there was more corruption in the 400 AD than there had been earlier. So I don’t think corruption was the reason for the fall of the Empire. I would say much more the loosening of the social bonds, the loosening of the notion of citizenship and citizen responsibility.

INTERVIEWER: Because there’s people who frequently talk about the collapse of the Roman Empire and we’re talking about corruption. This is a point where the foamy mouth conservative smashes the table and they’re going, they’re having too many, too much sex with the wrong people. That’s why it all went wrong.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah, but they’ve been doing that for hundreds of years and they had their empire. So I don’t think we can say that.

INTERVIEWER: Oh really? Because there’s also other people who go, well, you know, it’s all about once a society starts playing with gender, that’s a sign that it’s in terminal decline. Is that another conservative fallacy?

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah, it is. I mean, the Romans will only tolerate so much of this. So when you get someone like Nero who’s playing very interesting games, he offends Roman sensibilities, he offends the conservative morality of Roman society. There’s a bunch of things he does and ultimately he is informed that he should commit suicide. That would be the honorable way out. He’s forced, he’s forced to do it. But I don’t think the case, the situation, the case of Rome is a case that these people were sexually corrupt and that’s why the Roman Empire fell.

Roman Moral Sensibilities

INTERVIEWER: And what were the Roman moral sensibilities around sex, sexuality, women, et cetera?

BARRY STRAUSS: Well, they were pagans. So I mean, on the one hand they can be pretty conservative. They have nuclear families, they have clans as well, on the other hand. And women had to be chased or they couldn’t be married. But on the other hand, they had the double standard. Roman men could fool around just as long as they weren’t fooling around with someone else’s wife, especially not another citizen’s wife.

INTERVIEWER: So they’re Italian? Basically.

BARRY STRAUSS: Basically, they’re Mediterranean. This is a Mediterranean society.

Key Differences Between Roman and Modern Society

INTERVIEWER: Yes. Well said. Very interesting. And in what other ways? What I’m really curious about, Barry, is to try and understand, you know, we do this in the modern world too. There’s this thing called mirror image bias where we assume that everyone’s like us. Right. But I imagine the Romans as a culture were quite, even though we are to a large extent descended from them, were quite different to us. What would you say are the key differences about the way they thought about things and the world and all sorts of things?

BARRY STRAUSS: Well, okay, some key differences. First of all, family was much more important to the Romans than it was to us. And your ancestors were much more important to the Romans than they are to us. The wealthiest Romans, when a member of the family died, maybe just the men, they would make a wax effigy, a funeral. Max and I kept these effigies in special closets to keep them cool in their houses. And whenever there was a new funeral in the family, they would parade these effigies of the great ancestors who had died. So the wealthiest Romans had this sense of ancestral responsibility and ancestral pride in their family.

Honor was immensely important for the Romans in a way that it’s not for us. I mean, we talk about reputation. But I think even reputation has faded a bit in our society from what it was 100 years ago. But honor was immensely important for the Romans.

Authority. So in our society, in our political system, we have constitutions, we have laws, we have traditions. The Romans had all that, but they also had something called auctoritas, from which we get our word, authority. But this is authority on steroids. Auctoritas. Auctoritas is the honor and respect you pay to someone, not because of the legal power that person has, but because that person is great and noble and powerful.

So the Roman Senate, for instance, had very limited legal power, but in the Republic, it was all powerful because of its auctoritas. It was understood that these were people that you needed to respect, you needed to pay attention to. Now, of course, having a system like that, originally there’s 300 senators, and there was one point there, as many as 900. Having a system like that, of course, is anti democratic and it is elitist. That’s the bad side.

The good side of it is that you get a number of people to buy into responsibility. And here you have all these wealthy people who are not saying, what I really only care about is my corporation. They’re saying, I care about the government. It’s important that I be part of the ruling group of the state. And societies that have an institution like that really have a leg up, because you have these people who are responsible. They’re not going to go sit, cultivate their own gardens, they’re going to be public spirited.

Another factor that makes the Romans different from us is their system of clientage. So Roman society has been described as a pyramid or a series of pyramids. And it gets narrower as you go up at the top are a few very wealthy people. And as you go down, as you go down the pyramid, you get, of course, poorer and poorer people. Everyone in Roman society has a patron. And everyone in Roman society, with the exception of the emperor, is a client. He’s somebody’s client. And it was felt that the responsibility of clients to their patrons and vice versa, was sacred.

So how would it work? Okay, so you’re a Roman senator and you’re going to want to go out to the Forum and you want to make an impression. Your clients are expected to accompany you. They might even have to be there when you wake up in the morning. Like Louis XIV, La levee du roi. There was something like that in Rome that you would be there for the senator or the emperor. And if you have a case in court, your client is supposed to be there to cheer for you. If you’re running for public office, your client is supposed to support you and get other people who support you.

The other side of the coin is what happens if there’s a crop failure and your clients are starving. You, as a patron, are expected to take care of your clients. So it’s a much more vertical society than ours. It’s a much less egalitarian society than ours, but it’s a society with all these ties.

The Roman Myth and Destiny

INTERVIEWER: Barry, was there a central myth to Rome in the same way that there’s a central myth for America, the American dream, that anyone can come, they can make it, if you only work hard enough and you believe in yourself and your abilities. Did Rome have that?

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes. Not that anyone could make it and anyone could be rich, but that Rome had a destiny. Rome had a destiny to rule the world, to tame the proud, as one Roman poet said, and to teach laws to other people. So there was a sense that Rome was greatness. And if you wanted to buy into this greatness, you wanted to become a Roman citizen and you wanted to be part of this great enterprise.

As I said, there were all these rebels, there are lots of rebellions against the Roman Empire, but people who are not buying this, but there are a lot of people who think it’s not just the Romans are powerful, they’re great. Look at what they’ve achieved. Look at their army, which is like no army that the world had seen before. Look at the city. Very early on, they think of Rome as the eternal city.

So it’s not a myth that the Roman dream, everybody gets to have a house in the suburbs and two cars in the garages. But rather that if you buy into Rome, if you can be part of Rome, you become part of this greatness. I think that’s a big part of it.

Roman Superiority and Conquest

INTERVIEWER: And sorry to jump in, Francis, I’m curious. This idea of Rome being essentially bringing civilization to other people, was this accurate? Were the people that they were conquering really quite inferior to them? You know, technologically, culturally, militarily, et cetera?

BARRY STRAUSS: They were militarily inferior. They weren’t technologically or culturally inferior.

INTERVIEWER: And some really.

BARRY STRAUSS: Well, technologically, the Romans had a few things that others didn’t. They were incredible road builders. And the Romans, to take the technology of the dome, I don’t know if they invented or not, but they take it to places where it hasn’t been before. Roman law. It’s not as if the Romans are the only people in the ancient world, but the Roman law code becomes particularly orderly and codified.

I would say the one thing the Romans have over others is they just have this fantastic military and they have a political system that’s immensely flexible and that draws on the loyalty of its own people and that is able to make ties, make new friends in the places that the Romans conquer. Romans are very good at this. These are not Nazis coming in in jackboots and killing everyone. Although the Romans are capable of genocide when it’s absolutely necessary. But we’ve had to do things nice. We don’t have to do things nasty.

INTERVIEWER: You really have to civilize.

BARRY STRAUSS: Cigarette? No. The Romans, they do engage in genocide from time to time.

INTERVIEWER: Well, Carthage would be one example. Right.

BARRY STRAUSS: Carthage, Jerusalem, Corinth.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, there are quite a few, then.

BARRY STRAUSS: There’s quite a few. There’s a small city in Italy whose name is escaping me. I’ll come back to me early on. Numantia in Spain. When the Romans conquer Gaul. Caesar brags that he’s killed a million people and enslaved a million people. But that’s probably a vast exaggeration. So maybe he’s only killed 100,000 and enslaved 100,000.

INTERVIEWER: And why did he do that? Was it because they resisted as much as they did?

BARRY STRAUSS: They resisted, right.

INTERVIEWER: Yes. So it’s kind of like the Mongols. Like, if you don’t resist us, we will. We will tax you and leave you. Leave you be, basically. But if you resist us, we’re going to slaughter you all.

BARRY STRAUSS: That’s right.

The Nature of Ancient Warfare

INTERVIEWER: And is that how basically warfare was always conducted in those times, or is that quite original? Unique?

BARRY STRAUSS: It depends.

INTERVIEWER: Unusual.

BARRY STRAUSS: If you’re fighting war against people who you consider your kin, like the ancient Greek city states, in general, no. In general, war was – I wouldn’t say it’s bloodless, but the casualties are much smaller. The wars typically are fought by battles, just one day. One day battles. It was much more civilized. It was much more like an athletic game, like an athletic competition, like a sport.

If you’re fighting people who you consider to be inferior to you, then the knives come out. And we see that again and again. So Alexander the Great, for instance, when he invades Central Asia and India, he engages in a kind of atrocities he hadn’t engaged in by and large, further west. Although he did engage in some atrocities there as well.

Christianity and the Roman Empire

INTERVIEWER: And Barry, did this change when the Roman Empire turned into the Holy Roman Empire? Because obviously the religion of Mars and the other gods is very, very different to the religion of Jesus Christ and Christianity, right?

BARRY STRAUSS: Well, really good question. Gibbon, Edward Gibbon about the decline and fall of the Roman empire in the 18th century, famously says that the empire was ruined by “barbarism and religion.” He blames Christianity for turning the Romans soft and making them incapable of resisting.

This is nonsense for a bunch of reasons. First of all, the entire Roman Empire was converted to Christianity with a few pockets that weren’t. But most – the whole thing was. The most Christian part of the empire is the eastern part of the Empire. That’s where Christianity has its deepest roots. That’s the part of the empire that’s not conquered by the barbarians. That’s the part of the empire that survives.

So if Christianity makes people weak, it makes them only selectively weak. It only makes them weak in the west, not weak in the East. For another thing, Christianity was a fighting faith. Christian language in the later Roman Empire is infused with militarism. And the idea of Christian soldiers, of soldiers of Christ is a very big metaphor. So the Roman Christians absorbed the militarism of pagan Roman society. So I don’t think Christianity has anything to do with the fall of the empire.

The Division of the Empire

INTERVIEWER: And when did it move from Rome to Constantinople?

BARRY STRAUSS: Great question. So Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor – even before him, the Romans had realized that the burdens of running this empire, I mean it’s a big empire 3,000 miles with pre-modern technology and that’s facing attacks on two frontiers, both east and West. It’s too much for any one individual.

So they decide they will split it. And they have emperors in the east and the West. Constantine doesn’t – he wants to rule the whole shebang. But more and more they’re dividing the empire. And ultimately by the end of the 4th century, the empire is now permanently divided between Eastern emperor and the Western Empire.

Constantine creates the city of Constantinople. Constantinople means Constantine City. He names it after himself, as many emperors made cities they named after themselves. And it becomes the new Rome, as it is ultimately called. It becomes the capital of the Eastern Empire. And in many ways it’s a wealthier city than Rome.

Rome itself ceases to be the capital of the Western Empire. Rome is something like Disneyland. It’s a place that people respect. It’s a university town in a way. But the real capital of the Western Empire is first Milan in Italy and then Ravenna in Italy. Milan is a base for the land army. Ravenna is a base for the Roman fleet also. For a time, the Roman Empire is governed from the city of Trier in Germany, in the Moselle river valley off the Rhine in what’s now Northwestern Germany. So the Western Empire is governed more and more from the frontiers, and Rome fades into the background.

INTERVIEWER: So then that becomes the preemptive capital, that becomes the main capital. And then how does that change the empire? Because the moment you change from an empire with one central location where everything is governed from into almost three, that must change practically everything, doesn’t it?

BARRY STRAUSS: Well, not everything, but a lot. It means there is a giant sucking sound of money and power going to the east, because Constantinople, Milan and Ravenna are military bases as well as cities. Constantinople is not just a military base. It’s a magnificent city. And also it has the best fortification walls in the world. And it has a fantastic location on a peninsula on the edge of Europe with Asia across the way. It’s very defensible and nobody takes it for almost 1,000 years after it’s founded.

The Fall of the Eastern and Western Empires

INTERVIEWER: And so when did that empire begin to degrade and fall?

BARRY STRAUSS: The Eastern Empire?

INTERVIEWER: The Eastern Empire, okay, so the Western…

BARRY STRAUSS: Empire falls in the year 476 A.D. The Eastern Empire continues in one way or another for almost a thousand years. Constantinople isn’t finally defeated until the year 1453, when the Ottoman Turks conquer the city.

However, the Eastern Empire remains a big empire for about 150 years after 476. New people come in and they conquer a lot of it, and that is the Arabs. The Islamic conquest conquers most of what had been the Eastern Roman Empire. And the Byzantine Empire, as we call it, is reduced mostly to what’s now Turkey, Anatolia, and part of what’s now Bulgaria and Greece and some of the islands as well.

They lose most of their territory, but they’re very well organized. They really are the heirs of the Romans. And they hang on, as I said, for almost a thousand years after the fall of the Western Empire.

Constantine’s Conversion to Christianity

INTERVIEWER: Barry, in terms of Christianity, coming back to this discussion, how does it happen that these people who throw the Christians, the early Christians, to the lions and suppress them by any means they possibly can, then adopt this religion as the state religion? Because I imagine Emperor Constantine, great, but I imagine by the time he says this is what we’re doing, there’s quite an upswell already of whatever.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah. We don’t know how many Christians there were. But you’re right, Christianity has spread quite a bit. Some people would say 10% of the empire, some people would say 30% of the empire, certainly not the majority, but we don’t know. But there are a lot of Christians and they’re in strategic places.

The Roman elite is divided. They’ve concluded, after all the problems they have, they concluded that the gods are no longer on their side and they need to do something. And the first thing they do is they create a worship of the sun. The S-U-N. They worship the sun as a God. And the next thing they do is to say, we want to double down on the old gods. We want to revive the cult of Jupiter, the chief God of Rome.

And while we’re at it, they say, do you know why the gods don’t like us anymore? It’s because we have these atheists who live among us, who – we have these people who don’t believe in the gods. They think there’s only one God. Those are the Christians. And so they turn on the Christians.

And the emperor before Constantine, a man named Diocletian, undertakes the great persecution of the Christians. When he tries to wipe out the church, it doesn’t go as he had planned. It turns out, although some Christians do recant and they accept the pagan gods again, there are a lot of martyrs. And as the saying goes, the martyrs, the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church. The martyrs impress people that this church ain’t going anywhere. And these people really believe.

So after Diocletian, there’s another civil war or two, and Constantine comes to the throne. Before he conquers the city of Rome, he has accepted Christianity as his religion. And the famous battle that he takes Rome, the battle of the Milvian Bridge, a bridge north of the city over the Tiber. He sees a vision. He sees a vision of the cross in the sky. And it says “in this sign, you shall conquer.”

And so when he becomes emperor for the first time in Roman history, not only are the Christians not persecuted, but they are supported by the emperor and his taxes. And now Constantine’s building churches. He builds the Church of St. John Lateran, which is still the Basilica of the city of Rome. He builds St. Peter’s, he builds a variety of churches.

He sends his mother, Helena, St. Helena, for most Christians. He sends her to what is then Palestine, the Holy Land, to find the places where Jesus walked and where the apostles walked and to build churches there and to try to convert the Jews who are still there and the pagans who are there, into Christianity and to encourage monks to move to the Holy Land and set up shop there.

And he closes pagan temples, or he doesn’t close them so much as he takes away public support from them. We’re not giving you any tax money anymore. You want to sacrifice expensive bulls, that’s your problem, buddy. But you’re not going to get any money from the Roman state anymore.

INTERVIEWER: Smart.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah. And so quickly people begin to convert to Christianity.

Constantine’s Motivations

INTERVIEWER: And why is Constantine himself? Is he just a true believer and this is what he’s doing or are there political and cultural reasons?

BARRY STRAUSS: I think all of the above. I mean, Constantine is a very powerful man. He’s a politician, he’s a warrior, he can be very violent. And why he becomes a Christian, we think his mother was a Christian. Christian tradition is that Constantine converts to Christianity and his mother then converts after him. But there are ancient sources who say otherwise in that his mother was Christian first. His father, we know, was friendly to Christians. He was not a Christian himself. There seems to be some family background for this.

Constantine sees, I believe it’s an eclipse of the sun. Maybe not an eclipse of the sun, but it’s a solar phenomenon. I’m afraid I don’t remember the scientific term, but the sun does funny things and he wants to – he says, I went and asked the priest to explain what was going on and they couldn’t answer it for me. The only people who could, the only people who could are the pagan priests. That is, the only people who would explain it to my satisfaction were the Christian priests. And he says that’s one of the reasons he becomes a Christian.

And the sun is really important because as I said, an earlier emperor had tried to establish the worship of the sun. Constantine’s father was a worshiper of the sun. He was a general, very high in the service of this earlier emperor. So Constantine is saying in a way, the Sun hasn’t saved Rome. So maybe the Son of Man, if you will, will save Rome. Maybe Christianity will save Rome.

Christianity as Both Compassionate and Militant

INTERVIEWER: And why did Christianity, which we now most people would conceive it to be a religion of compassion and mercy and the meek and all of that stuff. You mentioned that actually it was a very warrior religion at the time.

BARRY STRAUSS: It was both. That’s a really great question. It wasn’t just a fighting faith, although it was a fighting faith. But Christianity, like most religions, was extremely flexible.

Christianity arose in opposition to a lot in the Roman world. After all, Jesus was crucified by The Romans and St. Paul, St. Peter are killed by the Romans and the Christians are in trouble with the Roman state in big ways from earlier on. But by the time of Constantine, Christianity had become Romanized.

And Christian intellectuals, Christian thinkers had to a certain extent made their peace with Rome. If you would have looked for Christians in Roman society before the conversion of Constantine, you would have had a hard time finding them because they looked like everybody else. They dressed like Romans, they talked and acted like Romans. They just didn’t go to the temples. And they met mostly in private houses because by and large, churches were illegal.

One of the appeals of Christianity was Christian charity. And so Christians would “love each other,” as they said. And this was quite appealing to many people. That doesn’t go away. That’s still part of it. But what’s not a part of Christianity in the Roman Empire is “turn the other cheek.” They’re still Romans, they’re not going to turn the other cheek.

And one of the reasons for Christianity’s success is that it makes these compromises. And you can imagine why. Christians might say we can’t have everything that we want, but we don’t live in a perfect world. We live in the real world. So maybe we have to be warlike and maybe we have to have soldiers, but we can also do good deeds. We can also have charity, we can also spread the faith.

The Complexity of Early Christianity

BARRY STRAUSS: It’s complicated.

INTERVIEWER: It works. So it’s pragmatic and staying on the theme of Christianity. We have the Christian Church in Rome, which I associate with Catholicism, and then we have Christianity in Constantinople, which I associate with the Orthodox Church. Correct me if I’m wrong and I’m being silly, is that accurate that there’s two forms of Christianity being practiced in both of these?

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes and no. There are many forms of Christianity and as soon as you get Christianity, you get Christian heresies. We don’t have the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church yet. That comes later.

The Bishop of Rome does have a certain authority, and the Bishop of Rome is very important in turning back Attila the Hun. I mean, there are many stories about that. But the papacy, as we’ve come to know it, is still in its formative stages in this period. Likewise, the Orthodox Church is still very much in its formative stages.

But there are a variety of heresies. There is a Christian thinker, I believe, a monk from Egypt named Arius, who had a view that eventually becomes heretical. Don’t ask me what it was, because I’ve forgotten. But many barbarians, when converted to Christianity, are converted to Aryan Christianity. By the way, it has nothing to do with the Aryans and the Nazis. It’s named after a guy named Arianus.

And so there are all these disagreements. And even in the east, when the Eastern Empire survives, there are those who insist that Jesus was only of one nature, not of two natures. And they don’t believe in the Trinity in the same way that people do in Constantinople. And there’s huge disagreement, bad blood between the different groups in Christianity.

INTERVIEWER: But this must have destabilized the empire because what you’re now introducing is essentially potentially the beginnings of a religious civil war like we see with the Sunni and the Shias in Islam.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes, but I would maintain that it doesn’t destabilize them to the point where the Romans are incapable of fighting the barbarians. I think the reason the Roman Empire… I basically buy the military explanation for the fall of the Roman Empire, and behind the military explanation, the political, economic and social and cultural factors that made the Roman army unable to deal with the task. I don’t think religion played a very big role.

The Erosion of Citizenship and Military Decline

INTERVIEWER: And prime among this, from what I understood, and correct me, is that you’re not actually saying the Romans got worse at fighting. But what happened is because the concept of citizenship eroded, people were far less committed to the country in which they lived, and therefore they wouldn’t go and fight for it. Therefore they had to get essentially outsiders to fight on their behalf. And outsiders will never fight for your land the way that people who actually live there would.

BARRY STRAUSS: That’s absolutely true. That’s one factor. Another factor is you have to pay professional soldiers. And if the barbarians have come in and taken your land and you can’t collect taxes to pay your professional soldiers, you got a problem.

I would really contrast it to me like the opposite case is Britain in the Second World War. So here’s Britain that goes on fighting against the Nazis. When everyone else has surrendered, they’re out of the game. The Brits are doing it alone. They have a whole of society effort and it only works when you can mobilize all of society to do this again. I think the Soviets do the same thing. They can mobilize all of society. They do it, of course, in very different ways. The British aren’t shooting a lot of people for not going up to the front.

The Romans can’t do that anymore. They have this new challenge. The barbarians have gotten better, much better than they ever were before. And the barbarians have even worse. Why? They learn how to fight from the Romans and they, as I said, they start out in 50 tribes. It’s not so difficult to defeat 50 tribes. Divide and conquer is the principle the Romans always follow. But what if you now have four tribes? That’s it. And they’re organized, they’re grouped together and they’ve learned to fought because many fight. Many of them have fought in the Roman armies all their lives.

And they’re looking across the Rhine river and they’re saying “it’s pretty rich and soft over there. The pickings look good.” But the Romans still have a professional army. It’s not so easy. But then, oops, here come the Huns from Central Asia and they are really barbarians. They make the German tribes look kind of peaceful. They’re pushing them across. And these German tribes said, “we’re crossing the Rhine, we’re crossing the Danube, we’re getting into Roman territory. We don’t care who we have to kill because now we’re pretty good at fighting. And now we can take on the big boys, we can take on the Roman army.”

And now if you’re the Roman government, what are you going to do? You can’t call on the loyalty of your people in a way that Rome could have in an earlier period.

Warning Signs of Imperial Decline

INTERVIEWER: So what would you say if such a thick question is reasonable? I’d like warning signs that an empire or civilization is starting to trend in the wrong direction, what would you see?

BARRY STRAUSS: I would say we have these warning signs today. When you have a society in which the concept of citizenship fades, when you have a society in which in the earlier generation young people were taught civics as they were in the United States, but now they’re not taught it anymore. When you have a society in which young people were taught their country was good and they should be loyal and serve it.

You know, when I was growing up in the US we had to say the pledge of Allegiance every day in the classroom. But when you have a society, when that’s gone and when it’s not cool to do that, I think you’re in trouble. I think that’s a sign of society that’s in trouble and is going to have a hard time being resilient.

When you have a society that trashes its institutions, and when you have a society where you don’t have strong leadership, then you’re in real trouble. The Romans had all those problems. They had these warning signs. It works fine until… Well, it may be not fine, but it works until somebody outside comes along and says, “you know what? I think I’m going to conquer you.”

And we have that. Now, China. China is aiming at the United States. Maybe they don’t want to conquer us, but it sure looks like they want to conquer us.

INTERVIEWER: And why, why do you throw America off its pedestal? Maybe. But conquer really?

BARRY STRAUSS: Okay, maybe not. Maybe not occupy the United States, but definitely knock it off its pedestal. Definitely drive the United States out of the western Pacific. And they’re doing it in ways that are very threatening to the United States. The Chinese are very good at war. The Chinese way of war. If this is this too off topic.

INTERVIEWER: No, no, no, no, we love it.

BARRY STRAUSS: Okay.

INTERVIEWER: This is right on topic. This is where our audience have woken up.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah.

INTERVIEWER: Finally, another video about the collapse of the West.

The Chinese Way of War

BARRY STRAUSS: The Chinese way of war is based on the writings of Sun Tzu. If you haven’t read Sun Tzu, everybody should read Sun Tzu. It’s a great and important book. And Sun Tzu says the art of war. The art of war. “War is the art of deception. Deception is at the height of warfare.” He also says that “the greatest victory is not crushing your enemy.” He’s not Conan the Barbarian. “The greatest victory is getting your enemy to surrender without you fighting a blow.”

Now that’s kind of mind boggling if you think about it. And it’s not as if deception isn’t something that we have in the west, but it’s never been essential to the Western way of war as it is to the Chinese way of war. You familiar with the book Unrestricted Warfare?

INTERVIEWER: No.

BARRY STRAUSS: Oh, you should. I got to read it. It’s available online for free. It’s a book that was written by two Chinese colonels, I believe, in 1999, but in the late 1990s. And it basically says “we’re at war with the West. And the way to win this war is there are no limits and we have to subvert them from inside it’s not a matter of attacking them frontally, although eventually we’ll be able to do that. But it’s a matter of subverting them, subverting their institutions, subverting their culture.”

And this is the Chinese way of war. It’s a big part of the Chinese way of war. And this is the challenge that faces the west and particularly America today.

INTERVIEWER: So it’s a process of demoralization.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: Which is what Yuri Bezmenov talked about, who was a Soviet defector who basically made all those very same points. That’s what the KGB was doing.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes. I mean, the Russians were and are very good at this. As you know, Russia has no natural boundaries, at least not in the West. And so for many centuries they’ve used propaganda and they’ve used head games as a way of getting themselves a boundary maskirovka is something they talk about a lot. Camouflage. That’s a very big part of the Western, of the Russian way of war.

The Crisis of Citizenship in the Modern West

INTERVIEWER: You know, when you talk, Barry, I’m always… I was reading about this stat about this. I can’t quote the exact numbers, but the percentage of young people who are willing to go to war for their countries in the west are dismally low.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah, it’s… I think it’s even lower in Britain than it is in the United States. But it’s low. It’s low in both places. I mean, for me, the legacy that the central lesson of the classical world is citizenship and the importance of having a citizen state.

You know, the Greeks and the Romans don’t invent the city state. The Phoenicians had that, the Sumerians had that. But they do invent the citizen state. And that is a society in which there’s a notion of citizenship and there’s a notion that the citizens have a stake in the society and they’re willing to give something back to their society.

And that’s what the Romans lose. And as I said, they can survive without that until really bad times come and really bad times came. And then they were, you know, they were shooting blanks. They didn’t have what you needed in order to survive.

Restoring Citizenship: A Path Forward

INTERVIEWER: So let’s say I had the power vested upon me by the United States. I crowned you. Please, dear God, listen, I make it great again, but I anoint you Emperor Barry Strauss.

BARRY STRAUSS: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: Using the lessons that we have learned from the ancient world, what would you do to the United States? Or what would suggest, would you suggest policy wise, that could prevent us from going down this particular path?

BARRY STRAUSS: Well, I think we want to reintroduce the idea of citizenship. I mean, I do a lot of the things that we’ve talked about at this conference, the ARC conference that I just attended, we’d want to absolutely revitalize the idea of citizenship. And we have to do it when they’re young. Education is absolutely central to classical civilization and classical notions of citizenship.

So you have to educate people in what to me was like, not even controversial when I was growing up. Love your country, be patriotic, Find out what’s good about it, and certainly also learn its history and find out what’s bad about it. But say that on balance, as I think anyone in a Western society should. We live in good countries. We live in countries that we should love.

And as citizens, we have a stake in this society and we have certain rights, but we also have certain responsibilities. I think we have to go back to that. We have to educate people that way. We can’t go on. We won’t survive if we have an educational system and a culture that says, “we’re bad, we’re terrible, we’re the worst ever, they’re victims, we’ve done it, we’re bad, we deserve to do penance. And if we’re going to be conquered by outsiders, so be it, because we deserve it.”

They don’t really mean that. They have no idea what they’re talking about. Yes, but that’s the road on which I think societies that give up believing in themselves, that’s the danger that they’re exposing themselves to.

Rights and Responsibilities in Ancient Democracy

INTERVIEWER: It’s really fascinating you talk about rights and responsibilities because it seems to me that everybody always wants to talk about their rights. “This is my right. Don’t do that now. I have the right to this.” Very few people talk about the other side of the coin, which is responsibility. So let’s focus on that. What do we mean by that?

BARRY STRAUSS: Well, for example, in classical Athens, in Athenian democracy, one of the mottos was, “In Athens, we don’t say that people who don’t take part in public life are minding their own business. We say they have no business being there at all.”

Do you know what the ancient Greek word for somebody who doesn’t take part in public life is? Idiot. That’s idiotes. Idiotes is somebody who does not take, who is not a citizen, who does not take citizen responsibility seriously.

So the ancients didn’t really have a developed notion of the rights of citizens. It was mostly the privileges of citizens and the responsibilities of citizens. For the Greeks in particular, citizenship was, in a way, it’s analogous to our idea of owning stock in a company. If you are a citizen of Athens, you have a share in Athens. They actually use that language. You have a share in Athens, and as part of your share, you have to do your duty.

Christianity and Individual Rights

INTERVIEWER: Can I play devil’s advocate a little, Barry? I’m curious. Just thinking through this logically, firsthand, so first impressions. So it could be totally off base. But isn’t that really the problem with Christianity? Because Christianity says you’re made in the image of God. You have value and worth by virtue of the fact that you are human. You are endowed with these inalienable rights by your Creator.

And we seem to have a society in which we really do practice that. Like you’re born, therefore you have a whole bunch of rights and a bunch of things you’re entitled to. And you’re entitled to healthcare and food and shelter and all of these things, which goes completely at odds with what you’re talking about, which is your rights ultimately do come from your responsibilities. These two things are matched. And so you don’t get stuff until you do stuff.

BARRY STRAUSS: That’s a great question. I don’t think that Christianity says that you’re entitled to health care. One of the reasons the west has succeeded is that in the Middle Ages in Western Europe, they developed a notion of the separation of church and state.

It’s often been said by some really great historians that in a way, the defeat of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire was good news in the long term because what it meant was there was no longer a central authority, but rather there were a series of these small petty states. And the only reason culture survived in these barbarian states is because of the church. Beginning with the monasteries, and then later on in more open church institutions such as the university.

Universities were established by the church, but the church leadership and the secular leadership were at each other’s throats. And that turned out to be a really good thing because it created space. It didn’t allow either one of them to become supreme. And citizenship and the rights of individuals kind of sneaks in between the church and the state.

Human Dignity and Limited Government

One of the things that Christianity does give is it gives the idea of human dignity. And this gets from Judaism, of course, the idea that human beings are created in the image of God. That’s what it says in the beginning of Genesis. The Greeks and Romans didn’t believe in human dignity.

In Latin, the word dignitas, dignity means rank or station in society. Julius Caesar, when asked why he’s going to go to civil war rather than obey the Senate which wants him to stand down, he says it’s because “my dignitas is dearer to me than life itself.” My rank is dearer to me than life itself. It’s not a notion of human dignity.

But Christianity takes this notion from Judaism and it spreads it to everyone in the Roman Empire and ultimately all mankind. So people have inalienable rights, but those actually the declaration says unalienable rights, but we say inalienable. Now those rights, as the Declaration goes on to say, are the rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Those are real rights, but they’re also kind of limited rights.

And so from this conflict of church and state, ultimately the notion of limited government comes out. And so citizens have responsibilities to their government, but they also have responsibilities to their God. And those responsibilities are pre-citizen. They’re separate from being a citizen and ultimately they’re more important than being a citizen. But I think what’s good about the west is that we have a balance.

Balancing Historical Truth and Patriotism

INTERVIEWER: Well, speaking of balance, my other devil’s advocate question was going to be, I love devils. Well, I guess from, with my Russian background, I’m always trying ideas on in my head as I listen to them and as you. Well, I agree with you about the greatness of the west and the importance to teach children correctly about that.

And then I also think about what’s happening in Russia today, right, where a historian like you isn’t allowed to investigate or research certain things about Russian, well, particularly Soviet history, the Gulags and all of that. The crimes of Stalin are covered up. And in fact now there are lots of people who think that he was a great guy who did lots of great things. The huge atrocities that the Soviet Union committed in World War II.

Now look, without the Soviet Union, I think it’s very clear that we don’t win World War II. And so the sacrifices that were made by my ancestors, among others, were hugely valuable. That does not eradicate the terrible atrocities that also happened that we should be able to talk about. But in Russia all of this is prevented from being talked about.

So how do we balance our desire to give our children a clear eyed view of our history with also being avoiding that trap of becoming these militaristic, nationalistic people who think they’ve been perfect their entire history?

BARRY STRAUSS: Yeah, well, great question. But of course the Russians have a very different heritage than Western Europe does. They didn’t have the separation of church and state. They didn’t have this space where individual freedom and liberty could develop.

I mean, we want our children. The other value that we have to give them is freedom of speech. And in the ancient republics, the ancient city states, this was absolutely essential freedom of speech. And that’s another thing that fades under the emperors. Freedom of speech is taken away from the Romans bit by bit.

There is no freedom of speech in Russia. There’s limited freedom of speech in the Russian tradition. Maybe ironically, it was at its height in the late tsarist empire. Even then it wasn’t complete. There was a secret police, et cetera and so forth.

But I think we have to teach our children about the west, about its achievements, about this balance and about the classical heritage. And we should also teach them. It’s very fragile, it’s very precious. I guess it was Ronald Reagan who said something like, “Freedom is always only one generation away from being lost.” And I think that’s absolutely true.

Education and Western Heritage

You can’t have a citizen society, you can’t have a republic without educating the young. And one of the terrible things that’s happened in the United States in the last 40 years is that education has been taken over by people who don’t believe in the country’s good and who don’t believe in freedom of speech in the same way.

I mean, I think they should be absolutely allowed to have their opinions. I think it’s great that we have a clash of opinions, but we have to be very careful what we teach the youngest children. And I think it’s very dangerous to take the youngest children and just expose them to propagandas and expose them to woke ideas.

I think we want to build them up slowly to where they have the freedom of speech and thought, where they can judge for themselves. I never want my students to mouth the party line back to me. How boring is that? I want them to be able to stand on their own two feet and to be able to have the strength of mind to do that. And to do that, they need to learn about the Western heritage.

Property and Civic Participation

INTERVIEWER: There’s probably a millennial or a Gen Z listening to this on the bus or on the subway or whatever. And you’re talking, and you mentioned about having a stake, the Greeks talking about having a stake in the city.

BARRY STRAUSS: Right.

INTERVIEWER: And for a lot of young people and people in our societies, they see having a stake in society as owning property. So they’re probably thinking, well, I’m not being allowed to own a stake in society, therefore why should I believe it? They feel excluded. I think that’s probably a big part of it as well.

BARRY STRAUSS: I think it is. And I think here we have the problem that we talked about earlier, the concentration of wealth and the growing extremes between the rich and the poor. We have to have prosperity. It’s very clear that an Athenian democracy was based on prosperity for the middle class and the notion of citizenship as it develops in Greece.

And then Rome is based on the idea that you’re going to have a solid middle class. And so if the middle class is threatened, I think that’s the whole ball game is threatened. So I’m really glad that you made that point. And we have to bring prosperity back.

Closing Thoughts and New Book

INTERVIEWER: Barry, it’s been a superb interview. Thank you. We could do one of these every weekend. We wouldn’t run out of things to say. So thank you.

BARRY STRAUSS: You’re very welcome.

INTERVIEWER: Thank you very much for coming back on the show. Final question is always the same. What’s the one thing we’re not talking about that we really should be?

BARRY STRAUSS: You’re not talking about my new book, which is this great and wonderful book that’s going to be appearing in August 2025. “Jews versus two centuries of rebellion against the world’s mightiest empire.” And these two centuries, from 63 BCE to 136 CE are some of the most pivotal years in history. It’s the years when the temple is destroyed, Jerusalem is destroyed, when Judaism retools, and when Christianity is born. Few things are more important than that. And if you want to know where it came from, read my book, which is also a great read, if I do say so.

INTERVIEWER: Sounds fascinating. I cannot wait to read it.

BARRY STRAUSS: Thank you.

INTERVIEWER: Also, I cannot wait to go to Substack where you get to ask Barry your questions. So follow us on over there. Right now, what is your favorite what if moment from the Romans or Greeks? Are any particular stupid, drunken horny moments that changed your history that you particularly enjoy?

Related Posts

- How to Teach Students to Write With AI, Not By It

- Why Simple PowerPoints Teach Better Than Flashy Ones

- Transcript: John Mearsheimer Addresses European Parliament on “Europe’s Bleak Future”

- How the AI Revolution Shapes Higher Education in an Uncertain World

- The Case For Making Art When The World Is On Fire: Amie McNee (Transcript)