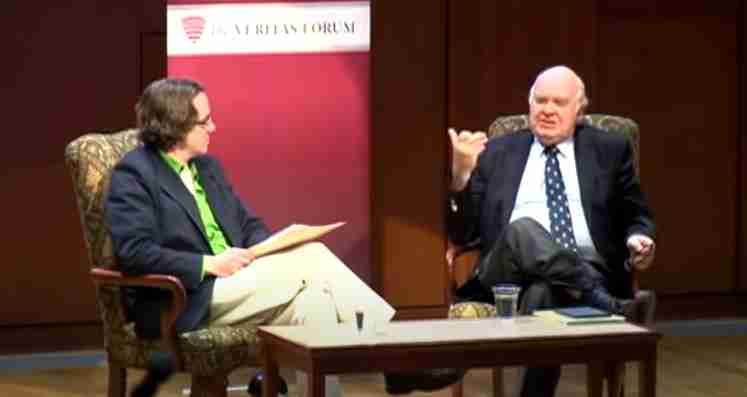

Here is the audio, transcript, and summary of a conversation titled “Why Are We Here? God, Life, and the Pursuit of Happiness” where Brown professor Linford Fisher questions Oxford scholar John Lennox on our highest values and treasured beliefs. This event occurred on 22 February 2013.

Listen to the audio version here:

TRANSCRIPT:

Linford Fisher: Well, good afternoon to all of you. It’s great to see everyone here, and I want to add my warm welcome to Professor Lennox. I’m so looking forward to this quaint Irish accent here as soon as you speak.

And I understand you came from St. Louis. It must have been the only airplane they allowed out of the Midwest. You made it here. I’m very delighted about that. It’s a privilege to have Professor Lennox here today. And it’s not often, perhaps, that mathematicians are the hobnob of historians, and certainly the same is true. I don’t hang out with mathematicians very often. And I’m desperately hoping that you don’t ask a difficult math question here on me suddenly because I won’t be able to answer it.

So Brown students have been braving the harsh weather and the storms and the snowfall over the past couple of weeks, trying to collect from their peers different kinds of questions to ask you about God, life, happiness, and purpose.

And indeed, there were hundreds of questions to sort through, many of them very, very good and difficult ones, and we won’t have time to address them all in this presentation, at least not formally. So we’ve selected the most difficult of all the questions, and we’ve saved them to ask you here this afternoon as a way of opening up a very honest and rich conversation about these topics here at hand.

So let me just reiterate that the questions I’m asking are not my own, although I have my own questions as well that maybe we can get to later on.

So to start off with, I actually have a sign from heaven even before we start. To start off with, I have a question that’s enormously important that I know has been weighing on all of our minds heavily since Sunday evening. The question is this, why did Matthew Crawley have to die in Downton Abbey?

John Lennox: Well, I understand these things catch on in America. All the goings on in English stately homes. But it’s interesting that you ask a question like that. It’s a bit like who shot J.R., isn’t it? So that dates me a little bit.

But we bring death up in the context of a soap opera or something like this, and somehow death is a fascination with people. And often we treat it in that remote sense as part of a novel, as part of the excitement and so on. But in reality, what we can be doing sometimes is substituting that for really facing the significance of death, which must, of course, inevitably come to all of us.

So I haven’t seen that episode yet. You see, I don’t like watching one episode at a time. I like to see the whole lot because I want to know what happens next. So I’ve yet to see it.

Linford Fisher: Well, now you don’t have to watch it, Eric, because you know how it ends. I’m sorry about that. I apologize. Spoiler alert.

Okay, so one thing I wanted to sort of start off with as sort of an opening question, which is not an official question, is to raise the question of why you do what you do. Here you are. You’ve debated. You’ve sat on the stage with people much more menacing and intellectually heavy than myself in many ways, Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens. You’ve debated them publicly, which not everyone would take on, certainly. And I wonder if you would just share a bit about why this has been something you’ve chosen to take on voluntarily.

John Lennox: Well, I suppose it all started when I got to Cambridge in the middle of last century. The Cambridge on the other side of the pond, as you will realize. And I come from a Christian background, and my parents are Christian, and my grandparents as well. And my first week as a student, another student said to me, do you believe in God? And he said, “Oh, sorry, I forgot you’re Irish. I should never have asked that question. All you Irish believe in God, and you fight about it.”

And of course, I’d heard that before, but somehow it was a trigger for the whole of my life. Because I thought, okay, could it be that my faith in God is simply Irish genetics, for instance? It’s just a Freudian projection. Everybody in Ireland believes and so on.

So on that day, I deliberately decided to get to know people that did not share my worldview, that had never been to church, that didn’t believe in God. And I’ve been doing that all my life. And that led me to Eastern Europe during the Cold War. And later, when the wall fell, I spent a lot of time in Russia, in the Academy of Sciences, still talking to people, to the world’s leading atheists now, about what makes them tick.

And the real motivation is simply this: I want to know what’s true. It’s okay to say that your faith in God helps you, and that’s marvelous if it helps you. But as a scientist, I’m actually interested in truth. And so I’m interested in exposing my worldview to serious questioning. So I spend my life doing that, and I’ve been very fortunate to be able to come up against some very tough questioners like Peter Singer or Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens.

And secondly, I think this because I feel that Christianity has been downgraded intellectually in many people’s minds. The default position in the Academy, in the Western world at least, is naturalism. And people assume that naturalism is true. I challenge that. And therefore, as an academic, as a scientist, as a professor of mathematics at Oxford, I want to step into the arena and say, just a moment, there is a rational alternative to this naturalism. And so I have sufficient confidence in people’s ability to distinguish, to judge. Let’s have a public debate and let the people judge.

And that is, by the way, why I’m greatly honored to be in this very famous university. I’m delighted to see that you believe in having this kind of a dialogue. It’s so important to students, particularly, that we’re exposed to different worldviews.

Linford Fisher: Thank you. I’m going to bank on the dialogue versus the big framing that you just gave. So in that spirit, the first question that does come from the students here has to do with American history, which is something that I love and know a bit about.

The Pursuit Of Happiness

The question is this: The Declaration of Independence famously describes our inalienable rights as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, which, by the way, I saw is also in the Rock lobby. It’s a John D. Rockefeller quote that he also quotes as well. For all of you who love the Rock, nobody. As a non-American then, how do you think about happiness? How much should we invest in the pursuit of happiness?

John Lennox: Happiness is, of course, like many of these terms, it’s difficult to define. It’s part of a whole spectrum of notions like joy, like flourishing, like fulfillment.

Now, from where I sit, every man and woman is a person made in the image of God and, therefore, having infinite dignity and worth and great potential. And I link happiness, true happiness, flourishing, joy, satisfaction with the fulfillment of that potential.

Now, if we follow that idea at a much lower level, here you are at one of the best universities in the world, and there’s a level of happiness in getting in. I take it you remember when you heard you’d got in? There was a joy. Now, that soon settles down. But then you begin to discover new ideas, and there’s another level of that sense of flourishing. Gosh, I could get interested in molecular biology, or I’d love to do Chinese applied basket weaving, or underwater lithography, or something like this.

And your interests grow, and then you begin to make friends. And as you mature, you have a sense of joy. I’ve got these friends, and they’re great. You can talk to them, and so on. So, I think all of those things are wonderful.

So, when the people fled from England to have a better life in America and founded this wonderful country, they had a great sense of trying to create an environment where flourishing would be possible. And I’m very aware, as I say this, that the reason they fled England was partly the persecution of the church. That’s such a horrific tragedy. We could come to that later.

But it is important to realize, and I’m just going to take this a little step further, because when you bring God into the equation, sometimes people say, well, you ought to be gloomy about God, because God’s out there to spoil your fun, and to see if you’re enjoying yourself, and being happy, and say, stop it. That’s nonsense.

God invented all the colors in the rainbow. We’ve never invented a new one. God is the one who has given us a universe utterly magnificent. I was looking up at the stars last night, and Orion’s nebula, and Jupiter’s sailing past, and just the sheer beauty and the vastness of space. And just think of your giftedness as a human being. You’re the top 0.01% of the elite of the world, by definition, if you’re here. Those magnificent gifts. I cannot conceive how people feel that God is a killjoy when He’s actually the author of these things.

So, to sum this up, I see joy and happiness at different levels. You know, when you’re about five, happiness is your face covered with ice cream. Some people older than that, I know, but there we are. But as you grow up, your joys come and go. There are things that you didn’t enjoy at seven. You weren’t probably reading Wittgenstein. But when you reach 77, you might be enjoying Wittgenstein, and so on. Joys grow.

And what I like to say about this is, we can put this in a much bigger context. I noticed the text coming in. That was most interesting. What is the most significant thing? It was friendship and family. That is relationship. Now, hang on to that. Because my firm belief, and it’s one of the reasons I am a Christian, is that God is not a theory but a person with whom we can have a relationship. Now, that’s true. And there is a God who invented and sustains the universe. Then, by definition, relationship with Him will mean the highest degree of happiness and fulfillment.

So we have all these other levels that we gain through our friends and our family, and they’re actually communicating a message to us. They’re telling us that our highest joys are found in terms of relationship, and they’re pointers upwards to the biggest relationship of all, which is the relationship with God.

How Do We Find Happiness?

Linford Fisher: Your mentioning of God as a killjoy, potentially, reminds me of H.L. Mencken’s definition of Puritanism. I’m sorry, I’m an early Americanist. I can’t help it. Which was, Puritanism is the fear that someone somewhere is having fun. Which is not the definition of Puritanism. Take my early American history class if you want a different one. And not the definition of God, I hear you saying as well.

But the question is, within religious structures and systems, there does tend to be this dour kind of killjoy mentality, right? And if happiness is a core value of our society, and indeed, Brown students consistently, nationwide, come in as the happiest students. Oh, do they? Absolutely. You can’t tell? Oh, you should have told me that before, because, you see, the obvious thing now is, if you want to be happy, go to Brown. So there’s no chance for me.

Well, that was the question, how do we find happiness? But I guess your answer is, you’ve already found it, you’re here at Brown. Okay. So let’s go back to, how do we find happiness? And I hear you saying it’s through relationships, and ultimately through a relationship with the divine. Yes. There’s a pinnacle of that. Are there other ways that even non-believers could pursue happiness that would be equally as satisfying? Is the pursuit of happiness limited to the Christian tradition?

John Lennox: Oh, not at all. Let’s get this clear. This is where part of the gloominess comes. I said right at the beginning, and this is my axiom, if you like, that every man and woman, whether they believe in God or not, is made in the image of God, and therefore, open to them, is the potentiality for all these levels of fulfillment and flourishing.

So an atheist like Francis Crick gets a tremendous buzz out of decoding the DNA, double helix. Of course, those levels are open, but by definition, relationship with God is not open to someone who denies God. And all I’m saying is this, there’s more to it than the naturalistic or atheistic worldview gives. Now that’s very different from the normal take. I see Christianity as a much bigger picture, giving me a bigger universe.

I mean, it’s pretty obvious, isn’t it? Because naturalism tells me that death is the end. So being nearly 70, I’m nearly at the end on average. And that’s all there is. What a tiny universe materialism or naturalism gives you. Whereas the Christian faith teaches me that death isn’t the end, that Jesus rose from the dead, that there’s hope that spins off into the future. And that adds an enormous dimension to that sense of happiness because as people get older, they see the end coming near, even if it’s in Downton Abbey.

As they see the end coming nearer. A friend of mine did epidemiological research on this, an old people, and he said it was very interesting. He discovered quite by accident, but then he made it an object of research, that people that had no faith in God, their event horizon collapsed very rapidly towards the end. They were living for the day, the hour, or the month.

But he said what astonished him was, by and large, people who believed in God, it was opening up, they were looking forward, not to the process of dying, but to the fact that death was not the end, and there was an eternity to be with God. That he found a very interesting thing, just as an established fact.

So, we can all flourish at some level or other. The atheist, as much as the Christian, can enjoy a NASCAR race. Especially with a woman driver, probably. No, you don’t follow NASCAR, obviously. Nor do I, but I’m proud of you.

Linford Fisher: So, let me just step back a minute. In terms of this idea of the meaning of life. So, you were saying that actually, a Christian worldview expands the possibility for meaning, not only in this life, but also beyond. Which leads into another question that people ask, which gets at the heart of this question of meaning.

So, demographers tell us that human life expectancy is at an all-time high on this planet, at around 80 years. You said 70, I think they’re saying now.

John Lennox: Oh, you’re giving me 10, thank you.

Linford Fisher: Around 80 years in the United States, at least. And it’s slightly higher in the UK. I’m not sure why that’s the case. Perhaps you can address that in your response.

But living longer doesn’t actually solve the basic problems that have haunted, or the basic questions that have haunted human beings from the beginning of time. It actually maybe exacerbates them because you have longer to think about these questions. Questions like, why are we here? What is our purpose? I’m curious what your response is to some of these questions. You’ve addressed a little bit, but if you could flesh some of that out, it would be helpful.

John Lennox: I wonder if my children put that question to me. Why am I here, Daddy? And I’ve often wondered, what would I say to them? Well, I know because I’ve had the question, and I have answered it. Do you know what I told them? Because I wanted you to be.

And one of the biggest things for me is this. If you ask that question as bluntly as that, why are you here? I can’t get behind this, that God wanted me to be. Now, somebody wanting you is a wonderful thing in life. C.S. Lewis wrote a brilliant article called The Inner Ring. And we all feel this. We come across a ring of people, and we’re in the outside. And we feel unwanted. And all of us have had this experience. It’s a terrible experience. Kids have it, grown-ups have it, and so on.

And when you come to the raw question of existence, and I’ve asked myself this question so many times, until I came across this magnificent statement. It’s in the book of Revelation, which is at the end of the Bible, and it’s full of the most magnificent descriptions of beauty and sound and music and vibrant with life.

And at one point, the whole universe is praising God as creator. And it goes like this. We praise You, our God, because of Your will they were and were created. Put that into contemporary English, it’s saying this. That ultimately, I exist because God, the God of the universe, wanted me to be. And that gives me infinite significance. And I see all of purpose at all the other levels flowing from that.

Now, that might not be the kind of answer you were thinking of, but it seems to me you can’t get behind that, you see. Why would God want me to be? Well, if you look at me, you’d wonder, wouldn’t you?

Linford Fisher: I wasn’t going to say anything.

John Lennox: Yes, of course you would, but it is true. And it’s so encouraging. Look at me, I’m not perfect. I have all kinds of hang-ups and so on. What a terrific relief it is to discover that there’s someone in the universe that wanted you to exist and accept you as you are. If you find a friend like that at Brown University, you’ve found a friend for life. Someone who accepts you as you are. I believe that occurs at the higher level. It’s only the start of the Christian faith. It’s not the end.

But to my mind, it’s one of the most significantly meaningful things that I’ve got. I’d rather have that than anything else. All the degrees I’ve got and all that kind of stuff. I’d much rather have that. That friendship at the highest level of a friend that actually wants me to exist. Of course, that raises a lot of questions.

Linford Fisher: So you’re saying you disagree with Calvin in the Calvin and Hobbes comic strip at the beginning there. That Calvin says, I am here so everyone can do what I want. This notion of contemporary selfishness is not the point, right? The purpose, as you’re saying, is beyond yourself. Beyond your own even intellect and experience in terms of God desiring you to be here for a specific purpose. But what is that purpose? I think that’s the core of the question.

John Lennox: Well, it relates to the survey as well for people who often objected, subjected them so on. And of course, logically Calvin, Hobbes, it’s possible, it’s a fairly desperately one. And it leads to the sort of narcissism and self destruction and everything else. But again what is the purpose? Well, I don’t think there is one purpose. The great catechisms of the church, man’s chief end is to glorify God.

But then you say, well, what on earth do you mean by that? Well, what I mean by that is that part of the purpose for me is doing abstract pure mathematics. Now, you may find that the most boring, unhappy kind of concept you ever came across in your life, which just shows we’re different. But it seems to me that we get some clues.

Let me step back from this a little bit. If we want to ask ourselves, what is the purpose for humanity, then one of the books, the great books of literature that has influenced me more than any other is the book of Genesis with which the Bible starts. Because it fascinatingly gives us a very compressed but extremely profound language, ideas about what human beings are and therefore what their purpose is. And let me go through it very quickly if I may.

It starts with the notion that human beings are made of the dust of the ground. That is, there’s so much chemistry and physics. Now, a reductionist atheist will tell you that’s all you are. You’re just chemistry and physics, little elementary particles puzzling around, and that’s it. That’s what Francis Crick believes. Oh, no. The Bible says more. What it says is now that we are animate, we’re alive. Well, we know that.

Next level up. A little phrase that you might miss unless you’re interested like me in literature because literature and indeed history are immensely important disciplines. God made the trees good to look upon and good for food. How very interesting. Human beings are so much chemistry and physics. They’re alive. They’ve got an aesthetic sense. Now you begin to see where we can flourish. The satisfaction of our aesthetic sense. Some of you are artists. Some of you are musicians. I like to think of myself as a little bit of an artist in doing pure mathematics. There’s another little hint.

Then we discover that God puts human beings into a garden and the idea of taming the world because a garden is different from a desert, as you know, although if you look at my garden in Oxford you wouldn’t be so sure. But the idea of a garden is imposing a discipline on our environment, letting plants grow. That gives enormous satisfaction and a sense of purpose.

But there’s more. We’re told that rivers went out of that garden and if you followed them along you would discover there’s gold and there’s various precious stones. What’s that talking about? Curiosity, ladies and gentlemen. When you see, when I do, a railway line, where does it go? A river, where does it go? Follow it along and you will discover things. As if God at the very beginning of this magnificent book is beginning to tell us what it means to be human in the sense of finding fulfillment and meaning. Follow the rivers. That’s what you’re doing in Brown.

Some of you are following the physics river. Some of you are following the history river. Some literature, some languages. But you’re following the river and exploring and then you’re doing something else. God started science, you know. That’s why I’m a passionate scientist. God isn’t anti-science. Not only is He not anti-intellectual, He’s not anti-science because do you remember one of the first things God told humans to do? I know it’s a simple story and some people trivialize it, but just take it seriously for a minute.

God told human beings to name the animals. That’s taxonomy. Every intellectual discipline involves names and things. You could come out with technical terms in history, couldn’t you, that I wouldn’t know about. And I could certainly come across, come out with some technical terms in math that you wouldn’t have a clue about, I suspect.

Linford Fisher: That’s what I’m afraid of.

John Lennox: Yes, well, don’t worry. I’m not going to do it. But we’re all like that. We’re naming things. There is immense satisfaction to be got in naming things. That’s what science, that’s what literature, that’s what the humanities are all about. Do you see what’s happening here? Instead of the Bible closing down and turning the world into a gloom, it’s opening up the possibilities. So what have we got? An aesthetic sense.

We’ve got the discipline of a garden and causing things to grow and plant life and nourishment and all that that means. We’ve got the aesthetic sense. We’ve got science and taxonomy. Is there anything else? Yes, there’s work. Work in the garden. That’s part of what it means to be human.

And the problem is, ladies and gentlemen, it’s very ironic to me. At every one of these points, there’s a philosophy in the world that cuts life off at that point and doesn’t go further. Life is just physics and chemistry. That’s materialism. Or life is just the pursuit of aesthetics. That’s hedonism. Or life is just work. That’s the old Marxist view. Or life is just…

And here’s the interesting thing. The Bible tells you more about life than any of these philosophies, which is one of the reasons why I believe it. And you creep up a bit further. It’s not good for man to be alone. There’s a relationship with someone, yet someone who’s other. And it’s building up to the fact that the highest definition of life is a relationship with God, which is morally defined.

And there’s another big wealth of meaning coming in because we human beings made in the image of God are moral beings. We’ve got a knowledge of right and wrong. We can say yes or no. And, of course, that capacity is the capacity that is at the back of the fact that we’re capable of loving one another.

So sorry to go on about that, but it seems to me to be important because we’ve got such a wealth of pressure from the other side, saying that anything with God in it cuts you down. In fact, it does the exact opposite.

Linford Fisher: Which is interesting because don’t you think there’s a bit of a presumption from a Christian perspective in saying that only through a relationship with God can someone find ultimate purpose and ultimate satisfaction? Or, to say it slightly differently, do we really need religion, or specifically Christianity, to answer the questions about ultimate meaning and purpose? I mean, can’t people be fulfilled and be good at what they do without God in that equation?

I mean, here at Brown, the majority from the polls that I saw would come in either as atheist or agnostic about the existence of God, and yet I’m sure everyone in the room here feels like they live a meaningful, fulfilled life at some level in terms of relationships without that framework. So, how do you make that kind of reconciliation?

John Lennox: Oh, very easily, because I said it already, actually. Fulfillment, as I see it, occurs at different levels. Now, for my atheist friends, and I have many of them, they reject God, so that level is not there by definition. So, I mean, they can’t blame me for claiming that there’s a level higher. The question of whether that level exists, which I regard as the highest level, is not a matter of presumption, provided you’ve got evidence to back it up. It could be a matter of presumption in the other way. I can take exactly the same view of atheism and say what presumption to believe there isn’t a God when there’s evidence of God all over the place?

So, we can balance those two arguments out to zero. So, it’s better to say, right, what is your evidence? So, let me make it clear. I am not denying that my atheists or agnostic friends cannot experience life’s fulfillment. In fact, I affirm it for the very reason that from where I sit, even if they don’t believe it, they’re made of the image of God with all these potentialities that most of us agree about. I mean, the things I went through, there’s not an atheist that wouldn’t agree with practically all of them except the relationship with God.

So, your point about presumption is well taken in the sense that as a scientist, it’s not enough for me to simply assert it and say there it is, the Bible says it, so it must be true. I don’t take that naive view. You’ve got to step way back from this and say, right, what is actually the evidence that it’s true? And I think that’s what happens in this kind of a dialogue where forming worldviews, we hear the evidence for one worldview and the evidence for another worldview and we have to make up our minds on that.

So, I hope I’ve answered that because the idea of presumption and arrogance tends to come in when you’re making a dogmatic statement for which you haven’t the slightest evidence. But it’s perfectly possible to do that and what concerns me today in the academy is many leading scientists making the absolute dogmatic statement that naturalism is the definitive worldview. Science doesn’t tell us that. Stephen Hawking’s just come out with that. Dawkins says that. I want to challenge that.

I want to actually be fairer and say there is no default worldview. There is a family of worldviews around the place and each of us has to decide which worldview that we espouse.

Linford Fisher: It’s helpful to think about dogmatism being present on both sides, but I want to push you more on this evidence. I’m a historian, you’re a scientist. We both build our careers on the use and sort of the presentation of evidence in our various different ways. I would not necessarily give a student a passing grade if he or she brought forward the kinds of evidence I’ve heard sometimes in terms of the existence of God or something else.

John Lennox: Nor would I.

Linford Fisher: So, when you say evidence, what do you mean? And how do you come up with an agreeable solution to defining acceptable evidence that would actually please all parties involved?

So, the results from the Veritas survey here on campus show that approximately 40% of students, of most of you out there, believe in God. 40% believe in God. Surprising, huh? 20% of students don’t believe in God and 40% said they weren’t sure or that we can’t know. And as one respondent candidly put it, what’s up with the lack of religion among our generation? There were other responses as well, but that one stuck out to me.

Evidence For The Existence Of God

So, people have their own reasons for believing or disbelieving in God, but since you push evidence so much, in your opinion, is there any strong evidence with the existence of God and how would you make that case to people who might disagree with the standards for evidence that you present?

John Lennox: Well, you just made my point for me in an indirect way. You said people have their reasons for believing in God and people have their reasons for disbelieving in God. That’s what I mean by evidence. It’s not proof. Proof only occurs in my field, pure mathematics. And even there, there are questions.

But normally speaking, we talk about pointers, evidence, indications beyond reasonable doubt. In other words, the kind of thing that historians, lawyers and so on work with. And we work with. All of us know about evidence. You know why you trust your friends. You know why you don’t trust some people. Et cetera, et cetera.

Now, it seems to be that this is a perfectly legitimate question to ask. All of us have our reasons. What are these reasons? Did you ask me what are my reasons? Well, let me give very briefly. There are two kinds. There are what I call the objective reasons that are out there, independent of me. And then there are the subjective reasons to do with my own experience and my own inner life.

And at the objective side, as a scientist, I would want to say that the nature is not neutral. That it gives evidence of the existence of God. I was in the God debate at Oxford Union the other week. You’ve probably heard of Oxford Union. It’s one of the most famous debating societies in the world, the university. We have a God debate every couple of years. And it was absolutely packed. They had to turn hundreds away. And we were debating this whole question of God and evidence.

And there was a professor of philosophy there who was an atheist. And he wrote to me before the debate. And he said, you seem to be a reasonable kind of person, interested in rational argument. Can you come to a dinner with 50 of my students and we’re going to grill you? Which is very nice. It’s nice to be grilled for dinner. And so I went. And we were talking. And it was most interesting.

Because in the middle of it, I said to Peter, this is the atheist professor of philosophy. If you were to make my case, what would you say? Oh, he said, instantly, what I’d say is you’ve got a strong case in the fine-tuning of the universe. He said, we’ve got to face the fact, as intellectuals, that the universe out there, revealed to us by physics and cosmology, has got this remarkable property of being fine-tuned, the constants of nature and so on. The precision is staggering. And he said, if I were you, I’d start there. So I said, fine, I’ll start there.

So it seems to me, ladies and gentlemen, that there is a start. But it’s bigger than that. There’s a fascinating book that’s just come out by one of America’s leading philosophers, who’s an atheist. His name is Thomas Nagel. And he’s written a book with the astonishingly provocative title. Just listen to it. Mind and Cosmos: Why the Neo-Darwinian Account Is Almost Certainly False.

Now, if ever there was calculated to be a title to get people thinking it’s that. Now, the very interesting thing is this. That one of my major reasons, evidences, for believing in God is the fact that science can be done. Can I explain that?

Linford Fisher: I would like you to.

John Lennox: Yeah. You see, what do I do science with? My mind. What is my mind? Well, my atheist friends tell me my mind is the brain. So what’s the brain? Well, it’s the end product of a mindless, unguided process. Oh, really? If you thought that your Apple computer was the end product of a mindless, unguided process, would you use it? Of course not.

Now, this has commonly been known as Darwin’s doubt. And philosophers like Alvin Plantinga and now Nagel are raising this in a big way. If naturalism is true, that is, it reduces everything to physics and chemistry and the laws of nature wherever they came from. Then what it does logically is to undermine the rationality you need to believe in that particular view, let alone to do science.

So it seems to me that naturalism in its extreme form doesn’t shoot itself in the foot, it shoots itself in the brain. Now, to confirm that historically, and you may want to comment on this, but it has fascinated me that modern science exploded in the 16th, 17th centuries with Kepler, Galileo, Newton, and so on, all believers in God. And that’s something that philosophers and historians of science have taken very seriously.

And C.S. Lewis, summarising Alfred North Whitehead, once put it this way, “Men became scientific because they expected law in nature, and they expected law in nature because they believed in the lawgiver.” In other words, ladies and gentlemen, one of the reasons why I’m not ashamed of being a Christian and a scientist is that arguably, with some nuances, it was Christianity gave me my subject. In other words, far from belief in God hindering science, it was the motor that drove it. Now, that’s what I mean by a kind of objective evidence.

Now, of course, I would want to come on the other side because I’m sitting here not simply as a theist who believes in an intelligence out there. I’m a Christian theist. So part of the evidence now comes straight back to your discipline because we’re not now talking about the rational structure of the universe. We’re talking about the intelligibility of history and things that happened within history. And that is one of the obvious things about Christianity. It claims to be geared into history. Jesus is a person who existed. He made various claims.

And so then I would want to come in on a whole lot of evidence which is why I’m delighted to be sitting with a historian because when I was at Cambridge, you know, one of the things that helped me enormously was listening to a distinguished historian analyze the evidence for the resurrection of Jesus from a purely historical perspective. I found that intellectually absolutely mind-blowing.

So I would want to come in there and then when I’d come in there, I would want to say, OK, these are massive claims. Jesus claims to be God incarnate. He claims to bring forgiveness. He claims to bring new life. Does it work? And then I become very subjective. You can’t see inside me. And all I would have to say there is over my entire life, increasingly, I find it works.

So all of those add together as what I would call cumulative evidence for the truth of the Christian faith. And I put it out there and other people put out their reasons, and we decide.

Linford Fisher: The subjective turn is intriguing and we don’t have time to go into it, so I’m just going to mention it and then run away.

But if that is one of the criteria then people would respond, I’m sure, judging from the responses from the survey, that that is present in every world religious tradition, that people would say that internally there’s an effectiveness to ritual and belief and practice. So just again, put it there and move on.

John Lennox: But that’s why you need the objective. That is precisely why you need the objective side. I can have all kinds of feelings. I can be sitting on the beach. Is there a beach around here somewhere? Probably. I’m sitting on the beach and the sun’s shining and I’m feeling wonderful. You’re up on a cliff and you see that the sea surrounds me and the tide’s coming in. My subjective feelings have no relationship to the reality of the danger I’m in. There’s an objective reality that is not remotely reflected by my subjective feelings.

So that’s why it’s both and — you’ve probably noticed that an eagle needs two wings to fly. So it’s exactly that. The objective confirms the subjective and vice versa. And so it’s the two things running in parallel. Once you only have the one, it’s sterile intellectualism and the other, it can be absolute subjectivism that has got no reference to any objective reality.

Suffering And The Presence Of Evil

Linford Fisher: So another question, this is shifting gears quite a bit, but I want to make sure we get to this because I think it’s a really critical one and in terms of thinking about the objections to religion and to Christianity on a global scale, one thing that comes up time and time again is the question of suffering and the presence of evil. And so I want to make sure we have time to address this.

So if you look around the world, if you watch the news at all, you know there’s a lot of pain, heartache, and suffering. And most of us here in this room likely really don’t know what it means to truly suffer. I’m not talking about having to suffer in Keeney Hall as a first year Brown student or to make the agonizing choice between an iPad and a Kindle Fire.

But something like, for example, the fact that every five seconds a child dies somewhere in the world from malnutrition. Or how every day thousands of young girls are forced into sex slavery and human trafficking. Or how millions of people are displaced in war-torn countries all around the world. And sometimes Christians are a part of the creation of suffering historically and in the present.

And you mentioned you’re from Northern Ireland earlier and this is a place where Christians have been a part of this religious strife and violence and political strife and violence. And so the question is, if there is a God, how can we account for this kind of human suffering on this scale throughout human history? How and why would a good God permit this kind of suffering?

John Lennox: Well, this is the hardest question any of us face. By far the hardest I face. And there are two questions there really. One relates to Northern Ireland, alas. And the other is the general problem. Let me just make a comment about the Northern Ireland thing because I was very fortunate.

My parents were Christian without being sectarian and they suffered for it. My father’s business was bombed. My brother nearly lost his life and so on because my father insisted on employing equally Protestants and Catholics. Very difficult thing to do. And so I didn’t grow up with all this sectarianism. But I understand the point.

I mean, I’ve seen sectarian violence firsthand. And so, very briefly, my reaction to it is I’m ashamed of it. Utterly ashamed of it, as a Christian. And I want to tell you why. I’m ashamed of it that the name of Jesus has ever been associated with an AK-47 or a bomb. Because He told His disciples not to use violence to promote His kingdom.

And the utter irony of this story is, historically, that Jesus was put on trial accused of stirring up political violence. In other words, the very accusation that is made in the question, and by people like Christopher Hitchens. And I understand the thing perfectly. I understand what’s behind it. It’s exactly what Christ was accused of.

And not going into the history in detail, He was declared to be innocent of it. And the important thing to realize is that He was declared to be innocent. Pilate could see He was no threat. Jesus said, “Yes, I’m a king, but My kingdom is not of this world. Otherwise, My servants would have been fighting.” And then He went on to say, “to this end was I born, and to this end I came into the world, that I might bear witness to the truth.”

And the famous statement of Pilate the governor said, “What is truth?” Perhaps not cynically, but he certainly knew that Jesus was no threat to him. See, ladies and gentlemen, you don’t use violence because the message of Christ has to do with forgiveness, peace with God. You cannot impose that kind of truth. In fact, you can’t impose any kind of truth by violence.

And if I may just put a little side comment in. Do you remember when the Christian disciples, two of them, took swords to defend Jesus, and they slashed about, and Peter wasn’t very good with a sword, so he tried to hack a chap’s head off and cut his ear off. Do you remember that? Well, Jesus put the ear back on. And one of the things I’ve observed is this, that wherever in the world people take weapons to defend Christianity, they’ll cut the ears off people in more ways than one. And we’ve got a big job, I feel I’ve got a big job to put the ears back on.

But let me come to your question, the hard question. You know, every time I get asked this question, it comes up all the time these days. I see a door, and over it are the words ‘Arbeit macht frei,’ in German: ‘Work will set you free.’ It’s the Iron Gate of Auschwitz. I’ve been there many times during the Cold War, and stood in the freezing cold of the snow, thinking of the thousands of people that died there. And I’ve wept every time I’ve been in there.

And you made very rightly the point that, you know, we suffer in Brown in the first year examination, or deciding between a Kindle Fire or an iPad. Suffering has two aspects, hasn’t it? Cancer looks very different to an oncologist than it looks to the young mother who’s just been told she’s six months to live. So there’s the theoretical side.

Now, in an audience like this, probably most of us, as we think of this question this afternoon, are thinking of it theoretically. But I bet it’s not all. And some of you are really hurting inside. And you’ve got this as a big existential problem. If there is a God, how can it possibly be that my mum has just been told she’s got Leukemia? Or that those kids die of malnutrition that could have been avoided if we hadn’t been so greedy?

And I want to be very sensitive to that, because many of my friends don’t believe in God. I understand them. It’s the one reason I really do understand. Believe you me? So the question is, how do I approach it? I’ve no simplistic answers. But I believe there’s a way that opens the door into a possibility of an answer that can be tailored to you and to me.

You see, ladies and gentlemen, many people tell me when they come across extreme suffering that they just give up on God. It blows the fuse. It’s too extreme. Forget it. God doesn’t exist. Many of my colleagues at Oxford will say, John, OK, there might be some intelligence out there. But don’t talk to me about a personal God. Don’t insult me. Because there can’t be a personal God. Just look at what I’m going through. And my heart goes out to them.

So what do I say to them? Well, the first thing is this, on the intellectual side. If you say, OK, there is no God. That’s it. That’s enough. I can’t take any of this anymore. There is no God. You have, in a sense, removed the problem. At the intellectual level, you come to the conclusion that this world is just a brute fact, that suffering is a brute fact.

You might even end up with Richard Dawkins, who says, this universe is just exactly what you’d expect to find it to be, if at the bottom there’s no good, no evil, no justice. DNA just is, and we dance to its music. That’s bleak. And I pointed out to him that it was bleak. And he said to me, yes, it is bleak, but that doesn’t mean it’s false.

I said, no, but it doesn’t mean it’s true either. So we’ve got to face that. Please notice, by the way, that Dawkins’ extreme materialist view removes the categories of good and evil. So logically, he cannot talk about a problem of evil. What does he get the concept of evil from, if there’s no category of good and evil?

Now, of course, he is a moral being, whether he believes in God or not, and that’s what he’s got the categories from, so he has every right to apply them. I do notice that what atheism does not do is salt the suffering. It’s still there. And it can make it 10,000 times worse. Because what atheism does, and it may be true at this point in the argument, it leaves people utterly without hope.

And what is more, it leaves the vast majority of people who have ever lived without justice. We are so privileged here today. You mentioned the children that will die during the course of our session. The vast majority of people who have ever lived didn’t get justice in this life, and if there’s no other life, if death is the end, they will never get justice.

So what atheism does is to almost negate the whole concept and say that our conscience that screams out for justice is an illusion. We live in a world where we get hungry, there is food. We live in a world where we get thirsty, there is drink. We live in a world where we cry out for justice, but there isn’t any. Is that really true?

So I come back in a circle. Hard as it all is, I now come back to bring God into the picture. Now ladies and gentlemen, the next step is this. People say to me, but look, here we see this awful behavior in computers just recently in this country. Couldn’t God have made the world differently? If He’s a good God and an all-powerful God, why? I mean, could He not? Shouldn’t He? If I were God, I would have. And those arguments go on for centuries.

Have you noticed nobody’s ever solved them? I’ve not solved them. So I ask a different question since I can’t solve that one. I say, well of course God could have made a world in which there was no evil. He could have made us all robots. But what use would that be? Because robots can’t love. I wouldn’t like to be married to a robotic wife, would you? Or husband? Who was programmed to kiss you when you pressed the iPad on her front that said kiss. Meaningless. God could have done it. He didn’t do it.

The fact is, well, I brought three children into the world. I took a risk, didn’t I? I can remember so well holding the little girl and thinking that child could grow up to reject me. Why take a risk? Well, you know why. Because there are things like love and so on and so forth. So, granted that there’s a risk, I come now to my question. I’ll stop at this point.

We look around and we see a mixed picture. I’m often reminded of Coventry Cathedral, beautiful cathedral in England that was bombed during the war. If you go to it now, you see traces of beauty and you see traces of devastation. That’s exactly what you see as you look around your world today.

Traces of beauty in human beings. Traces of utter devastation. That’s the way it is. So now comes my question. And it’s simply this. Granted that that’s the way it is. Are there any grounds anywhere of believing that there is a God whose love and attitudes are big enough for me to trust Him with those ragged edges?

That’s a big question, isn’t it? And here’s my answer to it. As I’ve said to many people around the world, I’ve said, you know, at the heart of what I believe as a Christian is that Christ was never merely a human being. He was God incarnate. And we all know He was crucified. So try and come with it. You may believe it. You may not believe it. But think of what is being claimed.

And what is being claimed is that was God on the cross. What’s God doing on the cross? Well, one thing it tells me is this. That it means that God has not remained distant from the problem of suffering, but has Himself become part of it.

A few years ago, if you don’t mind me being personal, I nearly died. I was within seconds of death. And I was rescued by brilliant surgeons who threw me onto an operating table and managed to sort me out. And people say, well, do you thank God for that? Yes, I do. But in that same year, my niece of 22, just married, had an earthquake in her brain. A colossal tumor. Gone. It’s all right for me saying thank God that I got better through medical intervention.

But what do I say to my sister? But my niece, although she died, she didn’t lose her faith in God. It was her faith in God that enabled her to cope with that. Why? Because the death of Christ on the cross wasn’t the end, ladies and gentlemen. I would have nothing to say if it was the end. But now comes the really big thing.

Because Christ rose from the dead, I believe death is not the end. And therefore, if you think of those innocent children that will have died by the time we’re finished this lecture, I firmly believe, and it may be risky saying it, ladies and gentlemen, but why not? It’s what I believe.

If you could see what God does with people like that, we’d have no more questions. I believe that God is ultimately a God of compensation, and one of the central claims of Christianity is our moral sense is not an illusion. There will be a final judgment at which justice will be done.

The terrorists will not get away with it. The man that destroyed your daughter by raping her or abusing her will not ultimately get away with it. Because this is a moral universe. And it’s that almost above all that is for me one of the most powerful evidences that the Christian faith makes sense.

I don’t regard that as a simplistic answer because we’re all left with all those raw edges. But at least I have seen in my experience, I haven’t suffered like some of my friends, particularly my Jewish friends. I haven’t suffered anything like that. But I have seen how that worldview coming in does something that atheism by definition cannot do. It brings hope, but hope that is based on something substantive back to the evidences for Christianity.

Linford Fisher: Well, thank you. We’re going to incur the wrath and justice of the people who are in charge of this building if we go on too long here. So I want to not ask the remaining questions and instead open it up officially into the Q&A, which I know that Professor Lennox likes to orchestrate himself. So I will turn it over to you.

John Lennox: Well, sorry if I went on too long about that, but you will ask big questions, sir. This is the point?

Well, what we’re going to do, ladies and gentlemen, just for a few minutes, one of the things I discover at these sessions is that everybody’s interested in everybody else’s question. So I’m going to give you a chance to hear the other people’s questions. So what we’re going to do is collect four or five questions before I say anything about any of them so that the whole room is aware of the spectrum of questions that are going through your mind.

So it’s a time, we haven’t much time as has been said. Get up, go to the microphone, I’ll acknowledge you, and state one question, not one question with 27 subsections. One question briefly, I’ll write it down, and when I feel we’ve got enough, we’ll come to that. So it’s over to you. So just come down to the microphone. Thank you very much. Number one, off we go.

Male Audience: Hi. I enjoyed the talk very much, thanks for being here. In just about every religion that we see throughout the world that’s arisen, there is a practice that involves entering into what many people call the ecstatic experience. It’s meditation and yoga in the East and entering into trance-like states in other cultures and other religions, but it’s there in all religions, and essentially it’s their means by which they communicate with God or with their equivalent to God.

And even in early Judaism and Christianity we see this, we see the prophets entering into visionary states to receive information and we see with Ezekiel in his vision of the cherry, we see with John on the Isle of Patmos, and some have even suggested that the Lord’s Prayer is a mantra of sorts. Anyway, my question is, what is the place of the ecstatic experience in today’s Christianity? Is that something that’s missing? Is that something that we’ve lost? And how do we reconnect with that? Thank you.

John Lennox: Okay, Two?

Male Audience: Hi, once again, thanks so much for coming and talking to us here. My question is that, you were mentioning at the end of your talk about this idea of justice and this idea that there will be, that there is, that death is not the end, that there is something that comes after that. And in addition, that whatever comes after that will somehow make up or justify some of the things that have happened, some of the suffering that has been incurred in this world.

So my question is, is there an implication in that statement that these children that are going to die from malnutrition, for example, that they don’t necessarily have to have known God or Jesus in order for there to be something good waiting for them afterwards? Thank you.

John Lennox: Okay, next.

Male Audience: Hi, thank you very much for a very interesting set of answers to these questions. My question relates to your — it goes back to when you were speaking about your personal background, about how you grew up in a non-sectarian background.

And I simply wanted to ask what place does organized institutional religion have within the framework of this generative, positive, generative and positive faith that you were, you’re an advocate of?

John Lennox: What place does it have in my life, or –

Male Audience: — what place does it have in the place of faith in general in God and how to best, in the experience of God? Does it have a positive or a negative place? There is….

John Lennox: Okay. Four.

Female Audience: So I was going to, I feel like this is probably a question you get a lot, but what you described, your view of God as kind of this ultimate friend and ally and someone who gives your life meaning and wants you and thinks that you specifically have this beauty, not necessarily to yourself. And that there is a justice and there’s life after, but how that kind of sounds to me like a coping mechanism and I feel like how do you see that as anything more than that?

John Lennox: A coping mechanism?

Female Audience: Yeah, just to…

John Lennox: Sort of aFreudian coping mechanism. Okay, I’ve got it. Five.

Female Audience: Hi. So you said that you wish to pursue truth, but then you also said that a reason to believe in God is the prospect of the afterlife because it provides hope. So I just want to know, is hope relevant to truth at all, and shouldn’t the basis for believing just be the search for truth?

John Lennox: Sorry, I can’t hear what you’re saying. Can you come closer to the microphone?

Female Audience: Yeah, yeah. Okay. I just wanted to know, do you think that hope is relevant to truth, or should the basis for us believing just be the search for truth?

John Lennox: Okay, I’ll take one more.

Linford Fisher: We’re supposed to be done by now, but…

John Lennox: Oh, right, okay, no more of that.

Linford Fisher: Let’s stop right there.

John Lennox: Let’s stop right there. Okay, these are going to be very brief answers indeed.

Linford Fisher: In three minutes.

John Lennox: Yes, and it’s a Q&A, ladies and gentlemen. I can only suggest the beginnings of answers here. The first question was the place of ecstatic experiences and so on, whatever that should mean. And it’s quite clear through history that many people claim, and indeed you get it in the Bible itself, claim very special experiences of nearness to God.

And obviously that’s an extremely positive thing. And the more we pray and get involved with God, clearly the more we will get to know Him, just as it is with our friends. There is another side to it. Because, of course, it is well known, and psychology shows it anyway, that it’s very possible for us to induce experiences.

And the Bible talks about those as well. And Paul, for instance, warns, because there were many extremely pagan religions, like the Baki in the ancient world, that got themselves worked up into colossal frenzy and produced visions. And Paul made a very big distinction between visions and experiences that actually proceed from God, that is God who’s out there, and visions and experiences that we dream up within our own heads.

And Paul points out that the danger is that if we haven’t a strong theological base and are holding on to what he calls Godhead, that is God, all kinds of things can flow up into our heads, some of them, which can be very dangerous indeed. Now, that’s something that I cannot explore here. The take-home message, of course, is none of us who’s a believer in God knows God as well as he or she could do or should do. And we ought to strive to improve that.

Now, the question of the place of organized institutional religion. Well, if I am a Christian, if I believe in God, God believes it’s good for me to mix with other people. Because if I only mix with myself, I’ll come away thinking, what a wonderful good boy am I. And I need other people to knock the rough corners off me.

Secondly, God has designed that there’s this wonderfully interesting thing, and I discovered as I go around the world, I go to a city where I’ve never met anybody, I meet a fellow Christian, and instantly I sense I’m at home. My mathematical colleagues have often remarked on it. I remember going to one obscure place and they said to me, we don’t understand you at all.

And I said, what’s the problem? Well, they said, you come here and you’ve got all these friends. We’ve never met anybody before who’s come out of the blue and has all these friends. And I was able to explain to them, this is what Christianity does. People share a common life.

Now, here’s the wonderful thing. We’ve all got different gifts and abilities, and I need what you can contribute to me. So there is a place for the institutions of organized church, but church in the Bible is not a building, it’s ecclesia, it’s a congregation, it’s a group of people. And one of the problems with the institutions is the impression it gives that God’s in a box, and you go and visit God every week, or if you’re very keen, twice a week, that God’s in the box, and that is a totally false idea.

The relationship, the personal relationship of God is primary. Its expression within the institution is secondary. If we make the institutional thing primary, we need to beware of the impression we are given. That needs a lot of qualifying.

Now, is my attitude a coping mechanism? Yes and no. A thing is not false if it enables you to cope. Neither is it true if it enables you to cope. And I think one of the best analyses of this has been done by Manfred Lutz in his book Eine kleine Geschichte des Größten, (A Brief History of the Great One), which is still only in Germany. He’s Germany’s leading psychiatrist, and he makes his point.

If there is no God, then Freud can explain brilliantly why belief in God and the resurrection and so on is a coping mechanism. If there is no God. But if there is a God, Lutz says, Freud will give you an equally brilliant explanation why atheism is a coping mechanism. To enable you to cope with the fact that you never want to meet God.

And he said, on the substantive issue, whether there’s a God or not, neither Freud, Jung, Frankel, or anybody else can help you. You’ve got to look elsewhere. And so it’s very important to ask your question. That’s the question I started off with, remember, in Ireland. Was it simply Irish genetics, coping mechanisms?

But don’t kid yourself. If a thing is true, it’ll probably help you to cope. But it’s not true because it helps you to cope. You’ve got to have stronger reasons than that for believing in its truth.

Now, justice. Is there an implication of what I said, that children and infants don’t have to know God or Jesus? That’s another of these big questions. I’m going to sound very dogmatic here, but it’s very clear from Scripture that God will never judge a person for not knowing something they cannot know. Abram didn’t know Jesus, did he? He trusted God. That was a counter to him for righteousness. In other words, he responded to the level of revelation of God that he had. God will be utterly fair.

And God is more interested, if you don’t mind me putting it crudely, He loves those children much more than I do. But we can be utterly sure that the judge of all the earth will do right. They will be saved because of Jesus, but they may never have known of Him. Now, in order to theologically tease that out, I’d have to take you on a lengthy excursus, which I’m not going to do.

Finally, is hope relevant to truth? Well, it is if the hope is true. And it comes back to the other question. Christianity gives the enormous hope, but that isn’t enough. I want to know if that hope is based on evidence, if it’s true. And I just come around in a circle. The fact that it gives hope is not evidence that it’s false. But it doesn’t prove that it’s true. We’ve got to decide whether it’s true on other grounds. But if it is true, then it’s not surprising since it’s one of the central words itself.

And perhaps that’s a good case to stop because I believe that you have a motto in this universe. What is the motto, sir?

Linford Fisher: Well, we should all say it loudly and together perhaps, but…

John Lennox: Do you know what that means? In God, we hope. Well, it is clear to me, ladies and gentlemen, that if that is true in Brown, there is great hope for you. Thank you very much.

Linford Fisher: Please join me in thanking him.

Want a summarized version of this long conversation? Here it is.

SUMMARY:

The conversation titled “Why Are We Here? God, Life, and the Pursuit of Happiness” between Linford Fisher and John Lennox delves into questions surrounding faith, happiness, and life’s purpose. The discussion covers various topics, from the pursuit of happiness to the role of God in our lives.

Linford Fisher, welcoming Professor John Lennox, expresses his curiosity about the motivations behind Lennox’s engagements in debates with prominent atheists like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. Lennox reflects on his pursuit of truth, driven by his Christian upbringing and his desire to engage with differing worldviews. He emphasizes the importance of intellectual exploration and public dialogue.

The conversation begins with a light-hearted discussion about the popular TV series “Downton Abbey” and transitions into more profound themes. Fisher poses a question about the pursuit of happiness as outlined in the Declaration of Independence and how non-believers might approach the concept. Lennox discusses happiness as part of a spectrum of emotions and highlights the connection between fulfillment and realizing one’s potential. He notes that every person is made in the image of God, leading to infinite dignity and worth, and he links happiness with the fulfillment of this potential.

Fisher probes the idea that religious structures can sometimes be perceived as restrictive or joyless. Lennox acknowledges the misconceptions about God as a “killjoy” and emphasizes that God is the creator of beauty and joy. He suggests that happiness and fulfillment are found through relationships, with the ultimate relationship being with God.

The discussion touches on the pursuit of happiness for non-believers. Lennox clarifies that non-believers can still experience happiness and fulfillment, often derived from their achievements and relationships. However, he underscores that a relationship with God adds a dimension that extends beyond the naturalistic worldview. Christianity, in Lennox’s view, provides a larger framework that offers hope beyond death, which contributes to a more expansive sense of happiness.

The conversation turns to the topic of life expectancy and its relationship to the human search for meaning. While people are living longer, Lennox argues that this extension of life does not necessarily resolve the existential questions that humans have grappled with throughout history. He points out that the quest for meaning transcends mere longevity and is intimately tied to one’s relationship with God.

In summary, the conversation between Linford Fisher and John Lennox explores the concept of happiness, the role of God, and the pursuit of meaning in life. Lennox’s perspective, rooted in his Christian faith and intellectual pursuits, underscores the idea that fulfillment and joy can be found through various means, but the ultimate depth of happiness comes from a relationship with God. This dialogue encourages contemplation about life’s purpose and the interconnectedness of faith, happiness, and one’s relationship with the divine.

For Further Reading:

Why I am a Christian: John Lennox (Transcript)

The Loud Absence: Where is God in Suffering?: John Lennox (Transcript)

AI, Man & God: Prof. John Lennox (Full Transcript)

FULL TRANSCRIPT: The God Delusion Debate – Richard Dawkins vs John Lennox

[/read]

Related Posts

- The Dark Subcultures of Online Politics – Joshua Citarella on Modern Wisdom (Transcript)

- Jeffrey Sachs: Trump’s Distorted Version of the Monroe Doctrine (Transcript)

- Robin Day Speaks With Svetlana Alliluyeva – 1969 BBC Interview (Transcript)

- Grade Inflation: Why an “A” Today Means Less Than It Did 20 Years Ago

- Why Is Knowledge Getting So Expensive? – Jeffrey Edmunds (Transcript)