Read the full transcript of Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani’s interview on Endgame Podcast #196 with Gita Wirjawan, titled “The Biggest Mistakes of the US, China, and ASEAN”, Premiered Aug 21, 2024.

TRANSCRIPT:

Introduction

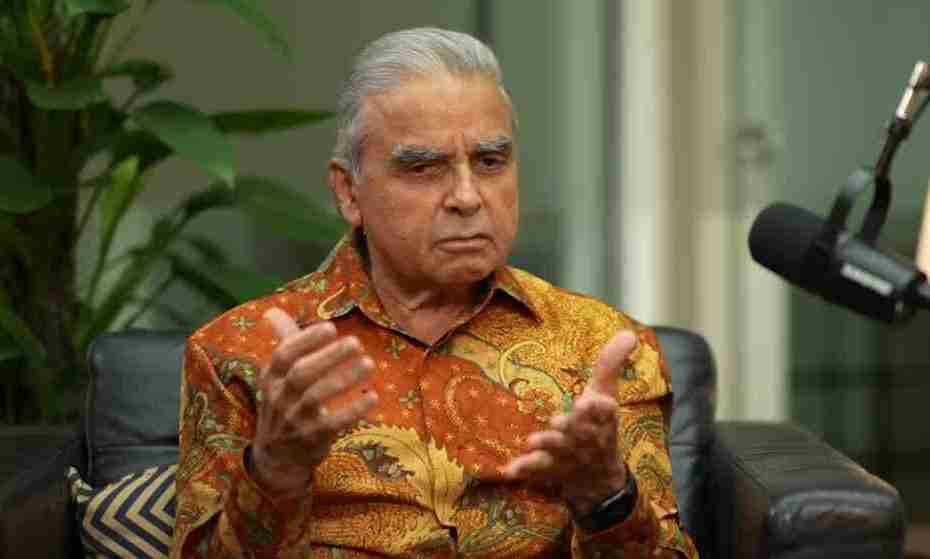

GITA WIRJAWAN: Hi, friends. Today we’re honored to have Professor Kishore Mahbubani, who’s the founding dean of the LKY School of Public Policy in Singapore. Kishore, thank you so much.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: My pleasure.

GITA WIRJAWAN: For coming again to our show.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I’m glad this time in person. Much better.

GITA WIRJAWAN: I know since the last time we talked in front of a camera, the world has changed. What would be your take on how the world has changed in the last two to three years?

Global Conflicts and Regional Stability

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, firstly, we’ve had two big wars that were big surprise. The first was the Ukraine war and the second was the Gaza war. And yet paradoxically, looking back, while there were surprises when it happened, you could also see very clearly the structural forces that were building up towards these two wars.

Secondly, of course, the US-China contest has accelerated and sadly will get worse over the next 10 years. The contradictions between the two are being baked into the system.

And thirdly, since it’s always good to throw in a bit of good news that while you see many troubled parts of the world, Southeast Asia overall it’s got challenges in Myanmar, South China Sea, ASEAN and Southeast Asia by and large are sort of quietly moving forward. And many of the countries within ASEAN continue to look very promising.

Ukraine War and Geopolitical Dynamics

GITA WIRJAWAN: Good. I want to touch on the situation in Ukraine. It seems on the surface and by way of some of the conversations I’ve had with other public intellectuals, it seems to be making China and Russia closer to each other.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I hope you don’t mind if I’m somewhat provocative and blunt in my reply. The Ukraine war is a disaster that is a result of European geopolitical incompetence. And I think we must call a spade a spade. Peace, as in Southeast Asia, reflects geopolitical competence. Wars as in Ukraine and Gaza reflect geopolitical incompetence.

The Europeans at the end of the Cold War had a golden opportunity to complete this centuries-long quest to bring Russia and the west closer together. If the European leaders had been wise, they should have found ways and means of engaging Russia wisely and integrating it into the fabric of Europe. But unfortunately after the Cold War ended, the Europeans haven’t had those kinds of long-range thinkers. They have progressively alienated Russia by supporting NATO’s expansion, which they must know would have angered Russia. And why anger an important neighbor of yours when the neighbor is going to be around for 1,000 years is bizarre. And it shows that the Europeans don’t understand that the world has changed and they have to adjust to a different world.

Now I have to add that paradoxically, on the Ukraine issue, the United States has been geopolitically very, very shrewd because the Ukraine war has been nothing but a positive for the United States, because here was China trying very hard to work with Europe as a strategic autonomous actor to counterbalance the U.S. but all the European hopes and aspirations for strategic autonomy disappeared as soon as the Ukraine war began. Because the Europeans realized, oh my God, we can’t defend ourselves without the United States. They have become far more dependent on the United States for their security. And as a quid pro quo, United States is saying, excuse me, if I’m with you on Russia, where are you with me on China? So the Ukraine war has been clearly a setback for Europe, setback for Russia, a setback for China, but a plus for the United States of America.

Gaza War and US Standing

GITA WIRJAWAN: Interesting. How is that also a plus for the US in the context of what’s happening in Gaza? Or it’s probably the other way around?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I would say the Ukraine war is a plus for United States, the Gaza war is a minus for the United States, because I don’t think we’ve had a war like the Gaza war happen in a long time because we’ve never had a situation where people can see in real time innocent civilians being killed. By the way, both the innocent Israeli civilians who were killed by Hamas terrorists and then subsequently the Palestinian civilians who were then killed in the Israeli retaliation against Hamas.

And it’s such a tragedy for Israel because Israel always had a certain reservoir goodwill in the world towards a state that they thought was, you know, in one way or another isolated or endangered. Now, I think survey after survey will show that the standing of Israel has gone down. And Israel has to deal with international judicial bodies like the ICJ and the ICC. And certainly, as even surveys in Southeast Asia have shown, the standing of the United States has gone down because it’s not been seen to play a constructive mediative role on Gaza.

Long-term Strategic Thinking

GITA WIRJAWAN: Would this be an event or a phenomenon where you think there’s scarcity of long-term thinking on both the Israelis and the US because there is this apparent juxtaposition of the declining moral value in terms of what’s happening in Israel with respect to the continuing support by the US towards Israel. And it’s not just, I don’t think it’s a good thing for both Israel and the US. I mean, on top of the fact that it’s much worse for the civilians, more on the Palestinian side.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I think what is missing in Israel and the US is any kind of serious long-range strategic thinking on what would be the ultimate solution to the Israel-Palestine issue. Now, in theory, Israel and the US are in favor of a two-state solution. In practice, Israel has been undermining the prospects of a two-state solution partly by the isolation of Gaza, but even more dangerously by having 6 to 700,000 settlers in the West Bank.

Now, if indeed you’re going to have a two-state solution, I don’t see how any democratically elected Israeli government can remove 700,000 Israeli settlers. I cannot see the Israeli army going in to shoot at Israeli settlers in the West Bank. So in a sense, Israel has created a situation which has prevented a two-state solution. And yet by preventing a two-state solution, Israel is condemning itself to constant warfare in one way or another with several of its neighbors.

And you know, Singapore, as you know, has been a long-standing friend of Israel. We want to see Israel do well. And if you as a friend see a friend of yours walking towards a cliff, do you say keep on walking or do you say stop? And I personally see Israel walking towards a cliff if it carries on with its current policies, because its current policies are based on the assumption that Israel and its strongest backer, United States, will always remain stronger than all the powers in the rest of the world. And that is certainly true for now, but that cannot be true forever.

And remember that in the Cold War, Israel was very careful about how it handled the Palestinian issue because it knew that states had an alternative. So if we move from a unipolar world to a multipolar world, and I have absolutely no doubt that we are moving into a multipolar world, it is not the same unipolar world in which Israel would have license to do everything it had to do.

So Israel therefore should start doing its long-term strategic calculations on what its place will be in a multipolar world and what adjustments it needs to make. And if it does those calculations, it will inevitably come to the conclusion that unless Israel works with the 140 countries that have recognized Palestine as an independent state, it will find itself progressively isolated in the world.

So I’m not arguing in terms of higher ethical values, I’m not arguing in terms of altruism, I’m arguing on the basis of hardcore selfish national interests of Israel. And these hardcore selfish national interests of Israel means that Israel must work for two-state solution honestly and realistically.

Multilateral Institutions and Personal Interests

GITA WIRJAWAN: Israel’s walking or apparent or seeming walking towards the cliff, is that also a manifestation of the fact that it’s not willing to listen to multilateral institutions and perhaps the declining capacity of multilateral institutions to enforce certain things or to reinforce certain things?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I think in many geopolitical issues, it’s very important to understand that there are layers and layers of complexity. So when you say that Israel doesn’t want to listen to multilateral institutions, it would be more accurate to say that it is the current Israeli Prime Minister, Netanyahu, who doesn’t want to listen to multilateral institutions or frankly, anybody else, because he has a personal interest that may override the country’s national interests.

It may be in the country’s national interest, let’s say, to have a ceasefire and maybe prolonged truce in the war in the hope you can get some Israeli hostages back, in the hope that you can save Palestinian lives, in the hope that you can bring calm to the region. But if that happens, it’s possible that Netanyahu may lose his job as prime minister. And if he loses his job as prime minister, according to Tom Friedman of New York Times, he may end up getting charged in court and he may go to jail.

So because of his personal interest in not going to jail, I predict that the war will definitely carry on at least until the presidential elections in the US in November. Because I believe Netanyahu wants to see Donald Trump being elected as president, and to see, even though he calls Joe Biden his friend, he wants to see Joe Biden defeated in the November elections.

So you can see, therefore, what is ostensibly a straightforward issue of war and peace is complicated by one person’s personal interests, complicated by the US Presidential elections. And these are the factors that are also at play.

But on the question of multilateral institutions, I belong to an endangered species called the true believers in multilateralism. And even though it’s conventional wisdom in today’s world to rubbish multilateralism, I believe in the long run, there’s absolutely no other way of managing our world except through universal multilateral institutions, especially the United Nations.

Strengthening Multilateral Institutions

GITA WIRJAWAN: Sure, you’ve written 10 books and you’ve talked a lot about your views about rejigging the UN, rejigging the Security Council, rejigging the way we see multilateralization going forward. Talk about that.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, it may appear that the solutions to strengthening multilateral institutions may appear difficult. There is actually one silver bullet we have that can rescue the UN immediately. And paradoxically, that silver bullet solution has been provided by a former American president called Bill Clinton.

Because Bill Clinton, even though his record as president, as you know, was mixed, partly because of personal reasons, he’s actually a very wise thinker. And in a speech in Yale he gave after stepping down as president in 2003, he said, if America is going to be number one forever, then fine, America can do whatever it wants to do. But then he added a but. He said, but if you can conceive of a world where America is no longer the dominant political, military, economic, cultural superpower in the world, then surely it is in America’s national interest to strengthen multilateral institutions, multilateral processes, multilateral rules, multilateral norms.

And he didn’t say this, but what he was implying is that then these multilateral rules and norms would then constrain the next number one power, which, of course will be China. So it was a very wise prescription. And by doing so, he was actually admitting what we all know to be the truth.

The reason why multilateral institutions have been weak, especially since the end of the Cold War in a unipolar world, is because it has been American policy to weaken multilateral institutions. In fact, in my book “The Great Convergence,” I actually cite a former director of the National Intelligence Council of the US telling me face to face, one on one, that, okay, Singapore may need strong multilateral institutions because they enhance the voice of small states like Singapore. For United States, multilateral institutions constrain the United States. So he admitted, the United States wants to weaken multilateral institutions.

But just imagine a world in which the United States realizes that it’s in its interest to strengthen multilateral institutions. And once it comes to that realization, everything changes. Because right now, we still have a window, because China is not yet number one. And the Chinese do believe that multilateral institutions are good. So if you can imagine a world in which United States and China agree that we should have strong multilateral institutions, then, voila, the problem has been solved.

GITA WIRJAWAN: What about the Security Council?

The UN Security Council’s Power and Reform

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, the Security Council clearly is by far the most powerful organization in the world, because only the Security Council can make decisions that are binding and mandatory on all UN Member states. So the United Nations Security Council imposes sanctions on Iraq, for example. We have to comply. You have no choice, because it’s a decision of the UN Security Council.

But the only way for the UN Security Council to survive is if its permanent members include the great powers of today or the great powers of tomorrow, but not the great powers of yesterday. And even though 80 years ago or 79 years ago when the UN was founded, clearly the five most powerful countries were United States, Soviet Union, China, UK and France. But 80 years have passed and I think neither UK nor France can be called world powers today.

UK is no longer among the top five economies in the world, neither is France. And UK sadly will not be among the top 10 economies in the world very soon. So clearly it would be wiser for the British to acknowledge that times have changed. And perhaps the best thing they can do to make up for the colonization of India is to acknowledge that India is now clearly, comprehensively the third most powerful country in the world after United States and China.

So why not give up its seat to India? And believe me, it will be a win-win situation because India is strong enough, powerful enough to deserve a seat on the UN Security Council. And the UK, once it is freed of having its hands tied in the UN Security Council, can act differently.

What do I mean by having its hands tied in the UN Security Council? The British could never do anything independent of the United States. So why put handcuffs on yourselves? By leaving this UN Security Council, the British are giving up their handcuffs and saying, “Okay, I am now a free and independent nation. I will pursue my own policies.” And frankly, the world is looking for countries to provide independent voices in this world because they are just tired of listening only to the great powers.

GITA WIRJAWAN: Do you see the UK as having the necessary humility and realism to do that? You know, in our lifetime?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: The British, it’s hard to believe this, but at one stage they could effortlessly run the world. Exactly a hundred years ago in 1924, a hundred thousand Englishmen could effortlessly rule over 300 million of my ancestors in India. Amazingly, it’s quite shocking. But you know, that frankly requires a lot of political and strategic acumen to be able to do that.

And of course it’s inconceivable for the British to send a hundred thousand Englishmen to run India today. I think they’d be massacred if they arrived in India today. But at the same time, there’s still some of that old acumen within the British intellectual traditions. And it’s still a country that has produced great writers, whether it’s Shakespeare, whether it’s Jane Austen, whether it’s Chaucer, J.K. Rowling.

So they do have a tremendous amount of intellectual capacity which they now should utilize to create an independent British voice in the world and not a subservient British voice which no one will respect.

Military Spending vs. Multilateralism

GITA WIRJAWAN: You know, the Cold War and post-Cold War international order would have been somewhat thick with militarism. And this is kind of manifested in the fact that if you take a look at the total defense budget of the world, it would have been about $2.75 trillion, of which the United States, NATO and their friends make up about $2.15 trillion. And you compare all these with the single multilateral institution which we call the UN, which is only with a budget of about $4 billion. What’s the hope for ushering this multilateral narrative going forward when everybody else is just piling up with defense capabilities and this one only sits with about $4 billion worth of budget?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, you know, in life there are lots of paradoxical truths. And one of the paradoxical truths that has been true for 2000 years is that if you want to enjoy peace, prepare for war. So in some ways, having lots of military expenditures doesn’t necessarily mean that there’ll be war if you have two very well armed states facing each other.

Like for example, the United States and China today, when both sides realize that war is not a win-lose proposition, that a nuclear war between United States and China will be a lose-lose proposition. Because even if the Chinese lose 30 to 40 cities, the United States would still lose 5 to 10 cities. And I can’t imagine the United States sacrificing New York and Washington, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago and Minneapolis to trying to win the war against China. It’s one thing to send soldiers to fight in the field, it’s another thing to have your cities obliterated.

So I think having those nuclear weapons creates a certain degree of reality. But however, I have to add that in the Cold War, most American leaders and Russian leaders and Chinese leaders were very aware of the dangers of nuclear war. Today, unfortunately, after 30 years of a unipolar world, American leaders and strategic thinkers have forgotten about the dangers of a nuclear war.

Because I think that while President Joe Biden was very wise at the beginning of the Ukraine war in insisting that American weapons should not be used to hit the territory of Russia because it could accidentally trigger a nuclear war, I’m actually quite shocked by the latest American decision to allow American weapons to be used by the Ukrainians to hit Russian soil. Because then you are moving one step closer towards nuclear retaliation.

At the end of the day, given the dangers of nuclear war, you know there’s a famous clock, Doomsday Clock. We are either two or three minutes away from doomsday once a nuclear war begins. So why not move that clock hand backwards rather than forwards? But to move that clock hand backwards you need wise long-term strategic leaders. And the west doesn’t have wise long-term strategic leaders today. And that makes the world more dangerous.

So therefore it’s not just a question of how many weapons you have. You also need to understand the dangers of these weapons and what they can do to your societies.

The Decline of Strategic Thinking

GITA WIRJAWAN: What explains the fact that the policy thinkers or makers in the west right now don’t seem to have the kind of long-term strategic thinking that we were used to seeing in the old days?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I must emphasize that the absence of long-term strategic thinking was confirmed to me by one of America’s greatest living strategic thinkers, Henry Kissinger. And you know, I saw him, I think about eight months before he died and I saw him in October 2022. And he clearly one-on-one was very worried about this incapacity of the west at large to understand that you got to deal with a very different world and that the west has got to make some adjustments in this world.

But the other reason why there’s this absence of long-term strategic thinking is because the generation of people like Kissinger or Richard Nixon, they had experienced World War II, they knew the horrors of war. But once you stop experiencing the horrors of war and once you assume that you’ll be superior forever, then you begin to do dangerous, reckless things.

And the sad part, you know, again, I say this as a friend of the United States. It’s a bit tragic that when you go to United States, you see a crumbling infrastructure, you see bridges collapsing in Pittsburgh, you see bridges collapsing in Baltimore, and you wonder why are you spending so much money on aircraft carriers fighting unnecessary wars like Iraq when you have much more pressing needs at home?

And indeed, surprisingly, a relatively conservative American thinker like Niall Ferguson has said in a recent article that “we Americans are the Soviets now.” And he’s right. Because if you look at it in the old Soviet Union, what was striking was declining life expectancy – in the United States today, declining life expectancy. In the old Soviet Union, rising infant mortality – in the United States, rising infant mortality. Stagnant living standards for the bottom 50% in the United States – stagnant living standards for the bottom 50% in the old Soviet Union. It’s actually quite striking.

So in a country that has so many domestic challenges, why not spend the time and effort to rebuild your own society? Because at the end of the day, as George Kennan said when talking about the Cold War, and I mentioned this in my book “Has China Won?”, that the outcome of the war is determined not by military weapons, but by the spiritual vitality of your own society. An American society is clearly a very deeply troubled society. Only a deeply troubled society would re-elect a man like Donald Trump as president.

And then by contrast, if you look at China, if you go to China, you’ll be stunned by the infrastructure that you see there. And the living standards of the Chinese people have improved more in the past 30 years than they have in the past 3,000 years. So that’s the real battle. So if the United States could focus more on improving the living standards of its people, less on projecting power overseas, it’d be better for the United States and maybe even better for the world.

Western Dominance and China’s Rise

GITA WIRJAWAN: You’ve alluded to the fact that the last couple of hundred years of Western domination would have been an historical aberration. To what extent do you think this will be short lived or long lived on the back of China’s rise?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I think it’s to give the west credit where it’s due. It’s actually quite stunning that these very small populations in the west first of all succeeded so spectacularly. I mean, delivering the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Industrial revolution, the scientific revolutions. I mean, frankly, if the west hadn’t modernized the world, you and I wouldn’t be sitting in this room in this incredibly modern environment all around us with this technology that all came in many ways from the West.

So the west gifted the world with modernization, and the world clearly has benefited a lot from the gift of modernization. But once that gift of modernization was shared with the world, then it was very clear that once the rest of the world could do exactly everything that the west does, the share of Western power of the world would shrink. It’s inevitable.

And therefore it would be wiser for the west to adapt itself to a world in which Western power has shrunk, but adapt intelligently, preemptively, instead of trying to resist it and refusing change.

To give you a very simple example, just to illustrate my point, it made sense in the 1940s for the Europeans to insist that the head of the IMF should be European and the head of the World Bank should be American. That made sense in the 1940s because United States alone had 50% of the world’s GNP and the Europeans were obviously going to recover and do very well.

But now, eight decades later, when the most dynamic, fastest growing economies are in Asia, how can you deny Asians from running the IMF or the World Bank? But that’s an example of how the mindsets of Western domination are so deeply embedded in the minds of Western leaders that they cannot do the obvious commonsensical thing, make way for somebody else.

GITA WIRJAWAN: This stickiness with respect to the old paradigm that would have dated back to the 40s can only be unlocked through a number of means, one of which is the continuation of the Chinese, the continuation of China’s rise. Right? China is just going to be much more dominant going forward and they’re going to be able to insist upon revising the pre-existing order. Or secondly, it could take again the humility or the realization by the west that perhaps some of these multilateral institutions should be headed up by an Indian, by a Chinese, by Southeast Asian, by an African or whatever. Are we likely to witness the end of engagement between China and the US?

Engagement with China: A Diplomatic Perspective

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I think nowadays no American leader dares to use the word engagement, right? Sadly, engagement is a positive human relationship, like just how you and I are engaging each other now, which is the most civilized thing to do. The normal position between two great powers should be engagement. But if you use that word in the United States, if any American politician says, “I’m in favor of engagement with China,” he’s dead, he’s finished. That’s how bad the situation is.

Now, your bigger question was, where is China heading? Is it going to disrupt the world order or become a supporter of the current world order? My answer is that will depend on how we treat China as it rises. Napoleon famously said, “Don’t wake up the sleeping dragon China, because if you do, it’s going to shake the world.”

You and I know there are two ways of waking up a human being. Either you wake up the person very gently, whisper soft things into their ear, nudge them gently, then they will wake up relatively happy. Or you could take a bucket of water and splash it on the person and say, “Wake up.” You can imagine how angry that person’s going to be.

Paradoxically, while the United States engaged China very well during the Cold War—from Kissinger’s visit in 1971 to roughly the end of the Obama era in 2016—for 45 years, the United States engaged China quite well. This actually created a China that had stakes in the current world order and became a responsible stakeholder in many ways.

But since then, the United States has decided to do the opposite and use all kinds of measures to stop China’s rise. Even though American society is bitterly divided and Trump and Biden don’t agree on anything, they only agree on one thing: it’s time to stop China. This is an unwise policy because it won’t work. You can’t stop China’s rise. China’s rise or demise will be determined by internal forces inside China. From outside, you cannot influence it.

If the United States continues taking measure after measure against China—tariffs, CHIPS Act, sanctions—clearly China is going to emerge as a very angry dragon. I wonder whether the West has thought about this and asked, “Is this what we want to see happen in the world?”

For us in Asia, our biggest mistake is that we can see the West creating an angry dragon. We know this angry dragon will be a problem for us, but we keep absolutely quiet while the West is making the dragon angry. That’s so unwise of us Asians. The trouble with Asians is that we are too polite. When the angry dragon is woken up, the United States may one day sail home and say, “I’m going home. I don’t care what happens.” Who’s left to deal with the angry dragon? We are.

Why aren’t we speaking out? Why aren’t we saying the most logical and obvious thing: “Hey, what are you doing? What are you trying to achieve?” We should be the ones acting to temper the forces trying to create an unnecessary conflict because our own interests will be endangered. But no leader has been willing to do so far. I hope that maybe your next president, General Prabowo, will speak out and express what is in the minds of many Southeast Asians.

GITA WIRJAWAN: Well, he has that instinct for internationalism, in my view. I think he’s going to be able to try to project Indonesia’s internationalism in whatever context possible, regionally or internationally.

The Opportunity for Global South Leadership

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, he has a massive opportunity in 2025, next year, because it will be the 60th anniversary of the Bandung Conference. I know you’ve had many conferences post-Bandung, but now in 2025, we really need a Big Bang Bandung conference.

As someone who travels around the world, I can tell you many countries in the Global South are very upset by this unnecessary emphasis on the zero-sum game between US and China because they feel their own interests are being damaged by this geopolitical contest. The Global South is looking for a way of sending a big message to both US and China: if you want to carry on this contest, go ahead. Don’t get us involved, don’t ask us to pick sides, don’t tell us “don’t buy Huawei.” We will do what we need to do.

Since this voice needs to be expressed, it needs a launching pad. A second Big Bang Bandung would be a way of sending a very strong message that the majority of people who live in the Global South don’t want to take sides in this US-China contest. In fact, they would like the US and China to moderate their contest, keep it within certain guardrails, and ensure that other global priorities like climate change, the next pandemic (I see bird flu may come back), or another financial crisis are addressed. Let’s focus on the problems that are most important for humanity and not put the zero-sum game about who’s the number one power in the world as the defining force in world events.

GITA WIRJAWAN: You’ve presented this argument very compellingly in the past, many times about the fact that not just Southeast Asia, but the Global South would have been very much used to multipolarity. What is specifically about Southeast Asia? I think people tend to underestimate the degree of agency that we have and we’ve been able to show for the past thousands of years. But in this tension between the US and China, what would be your prediction about what could or would happen with Taiwan?

Southeast Asia and the Taiwan Question

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: First, let me say a quick word about Southeast Asia, since you mentioned it. One of the biggest ideas that most leading Western minds cannot see is that the world of tomorrow will be very different from the world of yesterday, where the West dominated. They cannot see this new world.

Let me give everyone a shorthand view of understanding the world of tomorrow, and I’m going to call it the 3M world. The 3Ms that will define the world of tomorrow are: 1. Multi-civilizational 2. Multipolar, as you said 3. Multilateral, because in a small global village, you need multilateral institutions

Now guess which region in the world intuitively understands these three Ms? That’s ASEAN. ASEAN is a living laboratory of how the world can cope with this new world of tomorrow. The rest of the world should pay greater attention to what ASEAN does. I hope that President Prabowo will make an effort to explain ASEAN better to the rest of the world, because we have an amazing ASEAN story that hasn’t been sold to the world.

On your question of Taiwan, it’s very important to start with a key point: Taiwan is not an international problem. Taiwan is an internal Chinese problem. Even the United States has officially acknowledged a One China policy. A One China policy means that both Taiwan and China are part of one China. It doesn’t mean one China, one Taiwan. This is a basic point people keep forgetting.

I’m very glad that the Biden administration, especially after the very disruptive visit of Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan, emphasized that the United States has not backed away from its One China policy. You notice how relations between US and China stabilized a bit after San Francisco, because I think the United States gave a categorical assurance.

My hope is that if Donald Trump is elected president, he will also reiterate the One China policy. But unfortunately, some of his advisors may dangerously move away from that. His former Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, after stepping down, went to Taiwan and gave a speech recommending that the US should recognize Taiwan as an independent country. Mike Pompeo is an incredibly intelligent, sophisticated person. He knows that if the United States recognizes Taiwan as an independent country, he’s calling for a declaration of war by China against Taiwan. That’s why it’s very important that Trump’s advisors on China issues emphasize that he should reiterate that the United States remains committed to its One China policy.

Critical View on China’s Policies

GITA WIRJAWAN: Kishore, you’ve been a very big proponent of China, right? What would be one thing that you could perhaps be critical of with China?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I would say one of the biggest mistakes that China has made—and I’ll be very blunt here—is strongly endorsing the nine-dash line. We all don’t know where the nine-dash line came from. Professor Wang Gungwu, the greatest Asian historian in the world today, has said that the nine-dash line was probably created by the Japanese when they controlled China and Taiwan.

The trouble with the nine-dash line is that no one knows what it means. Many people think that with the nine-dash line, China is claiming all of South China Sea as its territorial waters. Clearly it isn’t. Every day thousands of ships go through the South China Sea without asking permission from China. If it were territorial waters, they would have to ask for permission.

It is a mistake to have a nine-dash line whose meaning no one knows. Looking back, one of the biggest mistakes made by some Chinese officials—I don’t think the decision was made by Chinese leaders—was to put the nine-dash line on Chinese passports. Once you put the nine-dash lines on passports, the Chinese government’s hands are tied.

The reason why I say their hands are tied is because it is not in China’s national interest to see the nine-dash lines succeed. China today is a global naval power. There are more Chinese goods traveling around the world than American goods. How can Chinese goods travel around the world? They need open seas. They need countries to adhere to a 12-mile territorial limit. It’s in China’s interest.

So why grab this small body of water in South China Sea and endanger your global interests? The South China Sea is what, 2 or 3% of the world’s oceans? Maybe 1%. Why give up 99% of the world’s oceans for 1%?

The nine-dash line, as I said in my book “The New Asian Hemisphere,” has become an albatross around the necks of the Chinese. The Chinese have got to figure out how to handle this carefully and sensitively because they need good ties with the ASEAN countries. The nine-dash line creates a point of friction between China and the ASEAN countries. Since this point of friction was created by China, China has to remove it.

GITA WIRJAWAN: As a fellow Southeast Asian, are you code of conduct optimistic with regards to resolving this quagmire?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I think more important than the code of conduct—I don’t know whether it’ll come about—is a clear understanding between China and especially the four ASEAN claimant states (Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei) that even while they have differences on the South China Sea, they will manage these differences peacefully and not allow it to ever come to blows.

So far, touch wood, we have done a relatively good job. We’ve had moments of tension, dangerous moments. That happens, but we’ve managed to resolve them. If we can get an explicit understanding between China and the four claimant states that differences will always be resolved peacefully, then I think we’ll be okay.

GITA WIRJAWAN: You, in your famous recent session in New York, alluded to how the Vietnamese see China. Anybody that wants to be the leader of Vietnam has to be able to stand up to China, but also has to be able to deal with it. Is that the kind of attitude that the other Southeast Asians ought to have, or is it just peculiar to Vietnam?

The China-Vietnam Relationship and Southeast Asian Dynamics

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I think you’re referring to my session with Orville Shell, the Asia Society in New York, which, as you indicated, seems to have traveled well around the world. I would say some aspects of the China-Vietnam relationship can also apply to other Southeast Asians. And certainly we in Southeast Asia must be able to stand up to China because China will become our biggest neighbors, but we must also be able to get along with China.

But at the same time, what is unique about the China-Vietnam relationship, which doesn’t apply to the other nine Southeast Asian states, is that the other nine Southeast Asian states have an Indic cultural base. Vietnam is the only one that has a Sinic cultural base. So there’s a kind of intimacy between Vietnam and China that is very deep and goes back thousands of years, because Vietnam is the only state in Southeast Asia that was occupied by China for 1,000 years.

And at the same time, the Vietnamese and Chinese have a very complicated relationship. And I’ll tell you one story which I told at Columbia University. Way back in the 1980s, when ASEAN and Vietnam were still fighting over Cambodia, I gave a speech at Columbia University. What surprised me was that in the front row were some Vietnamese diplomats at a time when Singapore and Vietnam were quarrelling with each other.

So I said, Vietnam and China have been fighting wars for 2,000 years. And I said, it’s not surprising that sometimes the Vietnamese armies defeat the invading Chinese armies. So in 1979, the Vietnamese army fought well against the Chinese army. But in the past, whenever a Vietnamese army defeated an invading Chinese army, the first thing the Vietnamese emperor would do would be to send tribute to Beijing and say, “I’m very sorry that I defeated your army. Please accept my apologies.” And I say, in 1979, Vietnam forgot to send the apologies. And you know what? The three Vietnamese diplomats went like this.

So, you know, there are some ancient relationships, especially in Asia. Another example is China and Japan. Fortunately, Ezra Bogle points out in his book on China and Japan, China and Japan have had the longest recorded bilateral diplomatic history. These two countries know each other very well. And for the past, out of the past 1500 years, they lived at peace for 1,450 years.

So it’s important therefore for us in Asia to nudge China and Japan back to the 1,450 peaceful year relationship rather than trying to push them towards an antagonistic relationship. Because this is where we, in Asia, certainly in Southeast Asia, we are too passive. We don’t proactively go out and make a difference.

And by the way, that’s why, frankly, one of the things I have done is to launch the Asian Peace Program at the Asia Research Institute of the National University of Singapore, because it is puzzling in our world that even though peace is so important, we spend so much more time and resources on wars and almost nothing on peace. So I hope that programs like yours will also help to encourage peace in Asia, for sure.

GITA WIRJAWAN: As a Southeast Asian, are you concerned with the formation of some of these blocks called the Quad Caucus and what have you? Well, in your view, would that erode the centrality of ASEAN or strengthened rather?

On Regional Alliances and Australia’s Position

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I mean, I have to emphasize that if countries choose to form or create an organization, they have a sovereign right to do so. So when India, China, Russia, Brazil and South Africa create BRICS, that’s okay, they have a sovereign right to do so. And countries have a sovereign right to join or not join, so they should have a right to do so.

But at the same time, sometimes these organizations send a signal. And I must say I was very puzzled by the Australian decision to form AUKUS because, you know, the UK has withdrawn several times from East Asia. They promised to defend Singapore till the death and they surrendered. They promised us they will keep the naval base in Singapore forever. And then they ran out of money and they left.

So the British today have such enormous domestic challenges. I was in Oxford a couple of months ago and unfortunately I fell sick. And I realized to my horror that one of the worst places in the world to fall sick is the United Kingdom, because you cannot get a doctor right away. And I’m not exaggerating. And after I hung on the phone with the National Health Service and I must have answered 500 questions, the final advice to me was, go and see a pharmacist. And I thought, this is bizarre. This is a modern developed country like the UK and it can’t provide basic medical services to its population. That’s bizarre. And then you want to go around the world and get involved in strategic challenges around the world.

And symbolically it was bad for Australia because at the end of the day, Australia’s destiny, Australia’s cultural destiny lies with the West. Its geopolitical destiny lies with Asia. And you know, I published a 5,000 word essay on Australia’s destiny in the Asian century. And one of the most obvious things that Australia needs to do is to understand its Asian neighbors better and work with its Asian neighbors better and understand that many of its Asian neighbors have been very kind to Australia.

So for example, ASEAN is a very valuable geopolitical buffer for Australia to cushion it from the rising China. In fact, ASEAN is like a pillow protecting Australia from China. But instead of appreciating this pillow and acknowledging that ASEAN is a valuable geopolitical buffer, some of the Australian governments have treated ASEAN with incredible condescension and even contempt. That shows very short-sighted thinking on the part of several Australian governments, not the present one, I must say.

I would say that Prime Minister Albanese and Foreign Minister Penny Wong have been done a good job of rebuilding their ties with Asia. But something like AUKUS is a signal that Australia is trying to sail backwards into history when the West dominated the world and not forwards into the 21st century where Australia has got to adjust and adapt to its Asian neighbors.

GITA WIRJAWAN: What do we have to do to dispel that perspective that there’s not adequate centrality within ASEAN or should we just ignore what the others think about?

ASEAN’s Strength Through Deeds, Not Words

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: I would say that ASEAN, the best thing that ASEAN can do is to sell its record not through words, but through deeds. So we have managed to have 33 plus 24, 57 years of peace of no wars among any two ASEAN member states. Let’s have another 57 years of no wars among any two ASEAN states.

And more importantly, let us continue to strengthen the ASEAN Free Trade area, continue to enhance areas of cooperation in ASEAN and as I was telling former Indonesian Ambassador Dino Jaral earlier today, enhance the strategic trust among the ASEAN countries.

So if we can provide to the rest of the world a model of strategic harmony in a very diverse region of the world, that’s the model that people should look at, look at it on a day-to-day basis and ask yourself why is it that Malaysia and Singapore can separate and become two countries and now have a close functional relationship? India and Pakistan separated much long ago. They have a dysfunctional relationship.

How is it that Southeast Asia, which in economic terms is much poorer than Northeast Asia, has had a successful Association of Southeast Asian Nations and Northeast Asia still doesn’t have an Association of Northeast Asian Nations? Why not? Why didn’t they learn from ASEAN?

And frankly, the easiest thing, you know, we have five ASEAN founding states, right? Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Philippines, five. Why don’t we take the five in Northeast Asia? China, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, Mongolia. Say, why don’t you form an Association of Northeast Asian States? Just talk to each other, just meet each other, just have regular meetings and play golf with each other. And guess what? The place will be a much better place. So these are the sort of lessons that ASEAN can teach.

GITA WIRJAWAN: It gets under narrated and it gets lost in translation or it just gets underestimated.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Yes. And in fact, I can tell you, I’m glad you mentioned the word underestimated, because there was a time in the past when Condoleezza Rice was the Secretary of State of the United States and she had to make a decision of whether or not to visit ASEAN or go once again to the Middle East to solve a problem. And one of her ambassadors in Southeast Asia called me up and said, “Kishore, help me. I got to make a case to Condoleezza Rice to ask her to come to Southeast Asia.” Unfortunately, she didn’t.

And you can see the United States Secretaries of State have paid far more visits to the Middle East. What’s the result? Look at Southeast Asia with American Secretaries of State have skipped so many ASEAN meetings. And what’s the result? Very simple. So let our record speak for itself.

GITA WIRJAWAN: More peace, more stability, more prosperity.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: And you know the ASEAN countries, it’s important for your listeners to know this. Between the years 2010 and 2020, ASEAN added more to global economic growth than all of the European Union combined. Isn’t that stunning?

GITA WIRJAWAN: Amazing. Yeah, amazing. What do you wish from the incoming leadership of Indonesia for purposes of strengthening the centrality of ASEAN?

Indonesia’s Special Role in ASEAN

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, you know, Indonesia has always played a very special role within ASEAN because at the end of the day, to be very candid, let me give you an example. The reason why the Organization of American States, which has been around longer than ASEAN, is a dysfunctional organization, is because the largest member state, the United States, wants to control the OAS, right? And says, if I don’t like it, your OAS will not do it.

The wisest thing that Indonesia has done as the largest member state of ASEAN said, no, you will not control it. Let everyone, let all of us run it together. And at the same time, you know, you’ve also injected some of your values into ASEAN. The principles of Mushawara, Mufakar, consultation and consensus. And they have worked.

So I think it’s very important first for Indonesia to take ownership of the ASEAN success story. And once Indonesia feels that this ASEAN success story is in many ways a gift from Indonesia to Southeast Asia into the world, then Indonesia should become the chief spokesman of ASEAN.

And since Indonesia has got embassies in more countries around the world than any Southeast Asian country, I think Indonesia should be actively marketing the ASEAN story. And certainly the year 2027, when we celebrate the 60th anniversary of ASEAN, we should make sure that everybody in the world understands and appreciates ASEAN and celebrates the 60th birthday.

GITA WIRJAWAN: Amen. Kishore, you’ve been a great product of intellectual curiosity. And that goes with Singapore also. How do you make sure that the other Southeast Asians become as intellectually curious as you are or as the Singaporeans are?

The Growing Awareness of ASEAN’s Uniqueness

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I’m pleased to report that, you know, I travel around Southeast Asia a lot. For some strange reason, I love Southeast Asia. You can see I dress like a Southeast Asian, except me. And as I travel around to Kuala Lumpur, to Bangkok, to Jakarta, to Manila, to Hanoi, and these are all places I’ve been to this year, 2024. And I can see that there is a growing awareness of how special we are in Southeast Asia.

You know, I attended a couple of months ago a one-day conference organized in Vietnam called the ASEAN Future Forum. I think it was so well done. And what touched me is that Vietnam is probably one of the newest members of ASEAN.

GITA WIRJAWAN: That’s amazing.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: One of the newest members of ASEAN hasn’t been a member that long.

GITA WIRJAWAN: I know.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: And the deep appreciation of ASEAN in Vietnam really touched me a great deal. And remember that Vietnam was an adversary of the founding member states of ASEAN until 1990, 34 years ago. And look at the difference between European Union and Russia. Why couldn’t the European Union deal with Russia in the way that ASEAN dealt with Vietnam? Right. We had been quarreling for a long time too.

So I mean, it shows there’s a certain lack of wisdom in the European Union. Its founding fathers had a lot of wisdom, but the current generation don’t understand that in a different world, a multi-civilizational, multipolar, multilateral world, that the European Union must make U-turns in some of its policies and not go by the tired old formulas of the past.

And they should also look for leaders who can think long term and look over the horizon of the new challenges coming and not just repeat the old formulas of the past again. So the European Union, sadly, I predict, is going to have a miserable decade ahead of itself because of its incapacity to adjust strategically to a different world. Whereas I think ASEAN is going to have overall a wonderful decade ahead because we have shown that we can adapt to a very different world.

The Power of Language in Southeast Asia

GITA WIRJAWAN: I want to test this hypothesis with you. If we were all going to be able to speak English the way you do in Southeast Asia, I mean, at the moment it’s the Singaporeans and many Malaysians and many Filipinos. The rest don’t articulate our stories. Imagine if instead of 60 to 70 million people in Southeast Asia, we have 3 to 400 million people that speak English. Imagine if instead of 10 million Indonesians, we have 100 million Indonesians who can speak English. We’d be able to tell the story to the world much better. Is that something that you think is worth trying?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I got some very good news for you. I’ve already solved your problem because I must say, I’ll be very honest with you. I am not an expert on artificial intelligence, but I am confident that with the advent of artificial intelligence, it should be quite possible. And as you know, nowadays I just gave a speech on. What day is it today?

GITA WIRJAWAN: Today is Thursday.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Thursday. I gave a speech on Sunday in Singapore to an audience, half of whom spoke English, the other half only spoke Chinese. Right. And behind me were two large screens, simultaneous translation. And even as I spoke, no human being did it. AI translated my words into Chinese immediately.

And according to a friend of mine who spoke Chinese, it was about 85% accurate. I bet you we’ll get to 95 to 99% accurate. So it’s very easy for an Indonesian to explain his views on ASEAN. Very soon, I’m sure it’ll be like as small as a phone and speak to it in Bahasa Indonesia and there’ll be a very fluent translation coming out.

So explain to an Argentinian, for example, you know, if there’s countries that have exceeded their potential, they are in Southeast Asia. If there are countries that have performed way below their potential, like Argentina. Remember Argentina was one of the top 10 most prosperous countries in the year 1900. Yeah. And look at where Argentina is today.

So I think Argentina should learn a bit about ASEAN. So the Indonesian should go speak to an Argentinian in Bahasa Indonesia and not have it translated into English, but into Spanish simultaneously using Spanish idioms to explain. Hey, if Argentina had been in Southeast Asia, your economy would be 10 times larger.

Rejecting Western Pessimism

GITA WIRJAWAN: Wow. Kishore, we’ve covered the world. Any final messages for us?

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Well, I think it’s very easy to become pessimistic in today’s world. And certainly when I go to Europe, all I encounter is doom and gloom. And to be honest with you, sadly, like you, I visited the United States four times in 2024 in the first six months. There’s also doom and gloom in the United States. Sadly.

Even though, by the way, the United States is an amazingly successful society, it would be a huge mistake for anybody to underestimate the United States of America. I have enormous respect for the US as a country. But sadly, many of the people are not happy.

So it is very easy for us in Asia to become infected by Western pessimism. So we in Asia should consciously. Consciously and forcefully reject Western pessimism and instead project Asian optimism. Because the 21st century will be the Asian century.

GITA WIRJAWAN: Amen. I’m with you on that one.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Thank you.

GITA WIRJAWAN: Thank you so much, Kishore.

KISHORE MAHBUBANI: Thank you.

GITA WIRJAWAN: That was Professor Kishore Mahbubani. Thank you.

Related Posts

- Transcript: Vice President JD Vance Remarks At TPUSA’s AmericaFest 2025

- AmericaFest 2025: Tucker Carlson on America First Movement (Transcript)

- Prof. John Mearsheimer: Unintended Consequences of a Meaningless War (Transcript)

- “It’s Really Not About Drugs” – Max Blumenthal on Mario Nawfal Podcast (Transcript)

- Erika Kirk’s Interview on Honestly with Bari Weiss (Transcript)