Here is the full transcript of American political scientist and international relations scholar John Mearsheimer’s speech on “”Europe’s Bleak Future” at the European Parliament, Nov 18, 2025.

Opening Remarks

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER:

Ladies and gentlemen, colleagues and guests, on this day, November 11, more than a century ago, the armistice was signed that was meant to end the war to end all other wars. How, one may ask, did humanity ever wind up there? After all, the Concert of Nations had secured nearly a century of relative peace. The nations of Europe have never before traded so extensively with one another or with the rest of the world. No one, it seemed, had any interest in war.

And yet, it came. “Sleepwalkers,” as Christopher Clark aptly described it. The armistice was not an end, but proved to be only a temporary pause, for the root causes of the conflict had not been addressed. The industrialized methods by which soldiers perished in the First World War would in the Second World War be applied to entire populations. The thirty years European Brother War left our continent utterly devastated: militarily destroyed, financially ruined, morally bankrupt, and politically subjugated.

From the ashes of the Second World War emerged a bipolar world order. European nations became engaged in political, military, and economic structures that either belonged to the so-called free West or to the communist East. With the collapse of communism, we entered a unipolar world led by the United States and guided by liberal values, free trade, and international relations institutions. That era has, however, ended with the rise of China, the financial crisis, and the scourge of Islamist terrorism. We have entered the age of multipolarity.

The European Union’s Strategic Dilemma

This means that the structures that encapsulated European nations, such as the European Union, must inevitably adapt to this new era.

The European Union has responded to Russian aggression in Ukraine by lofty liberal moralism, but we do not possess the hard power required to make such moralism credible. Consequently, we are dependent on weapons supplied by the United States to continue the war effort. This allows President Trump to impose highly unfavorable trade terms upon us, leading once again to dependency and to the degradation of our middle class.

The European Union has become the prisoner of its own strategic choices. Its founding promise was to ensure peace, security, and prosperity on our continent through economic collaboration. Yet in reality, its policy has led to war, insecurity, and impoverishment.

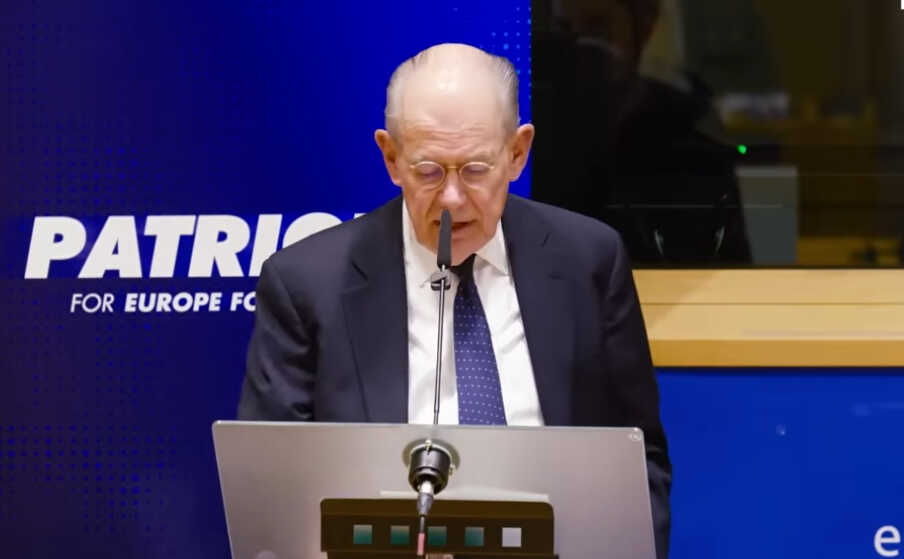

Introduction of Professor Mearsheimer

As a member of the European Parliament, I have the dubious privilege of traveling to Strasbourg every month. These long car journeys can be boring or are often considered a waste of time. But for me, these journeys are a true pleasure. For every time in the car, I am accompanied by the insightful podcasts of Professor John Mearsheimer on his Substack, with its sharp analysis and profound insights rooted in deep historical knowledge and academic expertise. It brings a necessary voice to the political debate, one essential for understanding the complexity of modern conflicts.

Professor Mearsheimer is a true intellectual giant, one of the very few of his kind still walking the earth today. Professor Mearsheimer graduated from West Point in 1970 and served five years in the U.S. Air Force. He received his PhD in 1980 from Cornell University, and since 1982, he has been a professor at the University of Chicago.

It is therefore both an honor and a great pleasure to welcome you on behalf of the Patriots for Europe Foundation here in the heart of the European Union to share your insights on the war in Ukraine and the way forward for Europe. Professor Mearsheimer, the floor is all yours.

Professor Mearsheimer’s Address

JOHN MEARSHEIMER:

Thank you very much, Tom, for that kind introduction. It’s a great pleasure and an honor to be here today to speak at the European Parliament. And I’d like to thank the Patriots for Europe for inviting me to speak here and thank all of you for coming out to listen to me speak.

Europe is in deep trouble today, mainly because of the Ukraine war, which has played a key role in undermining what had been largely a peaceful region. Unfortunately, the situation is not likely to improve in the years ahead. In fact, Europe is likely to be less stable moving forward than it is today.

The present situation in Europe stands in marked contrast to the unprecedented stability that Europe enjoyed during the unipolar moment, which ran from 1992—which is the year after the Soviet Union collapsed—until about 2017, when China and Russia emerged as great powers, transforming unipolarity into multipolarity.

We all remember Francis Fukuyama’s famous article, “The End of History,” written in 1989, which argued that liberal democracy was destined to spread across the world, bringing peace and prosperity in its wake. That argument was obviously dead wrong, but many in the West believed it for more than twenty years. Few Europeans imagined in the heyday of unipolarity that Europe would be in so much trouble today.

What Went Wrong?

So the question on the table is: what went wrong? The Ukraine war, which I will argue was provoked by the West and especially the United States, is the principal cause of European insecurity today. Nevertheless, there is a second factor at play: the shift in the global balance of power in 2017 from unipolarity to multipolarity, which was sure to threaten the security architecture in Europe.

Still, there’s a good reason to think this shift in the distribution of power was manageable. But the Ukraine war, coupled with the coming of multipolarity, guaranteed big trouble, which is not likely to go away in the foreseeable future.

Let me start by explaining how the end of unipolarity threatens the foundations of European stability. And then I will discuss the effects of the Ukraine war on Europe and how they interacted with the shift to multipolarity so as to alter the European landscape in profound ways.

The American Pacifier and European Stability

The key to preserving stability in Europe during the Cold War and all of Europe during the unipolar moment was the U.S. military presence in Europe, which was, of course, embedded in NATO. The U.S. has dominated that alliance from the beginning, which has made it almost impossible for the member states underneath the American security umbrella to fight with each other. In effect, the United States has been a powerful pacifying force in Europe.

Today’s European elites recognize that simple fact, which explains why they are deeply committed to keeping American troops in Europe and maintaining a U.S.-dominated NATO. It is worth noting that when the Cold War ended and the Soviet Union was moving to pull its troops out of Eastern Europe and put an end to the Warsaw Pact, Moscow did NOT object to a U.S.-dominated NATO remaining intact. Like the West Europeans at the time, Soviet leaders understood and appreciated pacifier logic. However, they were adamantly opposed to NATO expansion, but more about that later.

Some might argue that the EU, this institution here, not NATO, was the main cause of European stability during the unipolar moment, which is why the EU, not NATO, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012. But this is wrong. While the EU has been a remarkably successful institution, its success is dependent on NATO keeping the peace in Europe.

Turning Marx on his head, the political-military institution—here we’re talking about NATO—is the base or foundation, and the economic institution—here we’re talking about the EU—is superstructure. All of this is to say that absent the American pacifier, not only does NATO as we know it disappear, but the EU will also be undermined in serious ways.

The Unipolar Moment and Its End

During unipolarity, which again ran from 1992 to 2017, the U.S. was by far the most powerful state in the international system, and it could easily maintain a substantial military presence here in Europe. The unipolar world went away, however, with the coming of multipolarity. The United States is no longer the only great power in the world. China and Russia are now great powers, which means that American policymakers have to think differently about the world around them.

To understand what multipolarity means for Europe, it’s essential to consider the distribution of power among the world’s three great powers. The United States is still the most powerful country in the world, but China has been catching up and is now widely regarded as a peer competitor. Its huge population, coupled with its truly remarkable economic growth since the early 1990s, has turned it into a potential hegemon in East Asia.

For the United States, which is already a regional hegemon in the Western Hemisphere, another great power achieving hegemony, either in East Asia or Europe, is a deeply worrisome prospect. Remember that the United States entered both world wars to prevent Germany and Japan from becoming regional hegemons in Europe and East Asia, respectively. The same logic applies today to China in East Asia.

Russia’s Position in the Global Order

Russia is the weakest of the three great powers. And contrary to what many Europeans think—I’m sure many Europeans in this institution—it is not a threat to overrun all of Ukraine, much less Eastern Europe. After all, it has spent the past three and a half years just trying to conquer the Eastern one-fifth of Ukraine. The Russian army is not the Wehrmacht, and Russia is not the Soviet Union during the Cold War or the Chinese in East Asia today. In other words, Russia is not a potential hegemon in Europe.

Given this distribution of power, there’s a strategic imperative for the United States to focus on containing China and preventing it from dominating East Asia. There is no compelling strategic reason, however, for the United States to maintain a significant military presence in Europe, given that Russia is not a threat to become a European hegemon. Indeed, devoting defense resources to Europe reduces the resources available for East Asia. This basic logic explains the U.S. pivot to Asia. But if a country pivots to one region, it means that it’s pivoting away from another region. And of course, that other region that we’re pivoting away from is Europe.

The Israel Factor

There’s another important dimension, which has little to do with the global balance of power, that further reduces the likelihood the U.S. will remain committed to maintaining a significant military presence in Europe. Specifically, the United States has a special relationship with Israel that has no parallel in recorded history. That connection, which is the result of the tremendous power of the Israel lobby inside the United States, not only means that the United States will support Israel unconditionally, but it also means that American forces will be involved in Israel’s wars either directly or indirectly.

In short, the United States will continue to allocate substantial military resources to Israel as well as commit substantial military forces of its own to the Middle East. This obligation to Israel creates an additional incentive to draw down U.S. forces in Europe and push European countries to provide for their own security.

The bottom line is that powerful structural forces associated with the shift from unipolarity to multipolarity, coupled with America’s peculiar relationship with Israel, have the potential to eliminate the U.S. pacifier from Europe and cripple NATO, which would obviously have serious negative consequences for European security.

The Path Not Taken

It is possible, however, to avoid an American exit, which is surely what almost every European leader desires. Simply put, achieving that outcome—that is, preventing the United States from leaving Europe in a serious way—requires wise strategies and skillful diplomacy on both sides of the Atlantic. But that is not what we have gotten so far.

Instead, Europe and the United States foolishly sought to bring Ukraine into NATO, which provoked a losing war with Russia that markedly increases the odds that the U.S. will depart Europe and NATO will be eviscerated. Let me explain.

Understanding the Ukraine War

To fully understand the consequences of the Ukraine war, it’s essential to consider its causes, because the reason that Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 says a great deal about Russia’s war aims and the long-term effects of the war.

The conventional wisdom in the West, as all of you know, is that Vladimir Putin is responsible for causing the Ukraine war. His aim, so the argument goes, is to conquer all of Ukraine and make it part of a greater Russia. Once that goal is achieved, Russia will move to create an empire in Eastern Europe, much like the Soviet Union did after World War II. In this story, Putin is a mortal threat to the West and must be dealt with forcefully. In short, Putin is an imperialist with a master plan that fits neatly into a rich Russian tradition.

Challenging the Conventional Wisdom

There are numerous problems with this story. Let me spell out five of them.

First, there’s no evidence from before February 24, 2022, that Putin wanted to conquer all of Ukraine and incorporate it into Russia. Again, I want to emphasize: there is no evidence to support the conventional wisdom. Proponents of this wisdom cannot point to anything that Putin wrote or said that indicates he thought conquering Ukraine was a desirable goal, that it was a feasible goal, and that he intended to pursue that goal.

I want to repeat this: Putin never said that conquering Ukraine was a desirable goal. There’s no evidence to support that. There’s no evidence that he said he thought it was a feasible goal. And there’s no evidence that he said—this is all before February 24, 2022—that he intended to pursue that goal.

When challenged on this point, and as you can imagine, I’ve had many discussions with people who defend the conventional wisdom, they point to Putin’s claim that Ukraine was an artificial state and especially to his view that Russians and Ukrainians are one people, which, of course, is a core theme in his famous July 12, 2021 article that people often reference.

The July 2021 Article and Putin’s Stated Position

These comments saying that Ukraine is an artificial state, we’re saying that the Ukrainians and Russians are one people, say nothing about his reason for going to war. In fact, if you read the July 12, 2021 article that he wrote, which I’ve read many times, there is zero evidence in there that he was bent on conquering Ukraine. And in fact, he said exactly the opposite in that piece.

For example, he tells the Ukrainian people, and I’m quoting from that July 12, 2021 article, “You want to establish a state of your own, you are welcome.” Regarding how Russia should treat Ukraine, he writes, “There is only one answer with respect.”

There’s only one answer with respect. He concludes that lengthy article with the following words: “And what Ukraine will be, it is up to its citizens to decide.” That does not sound like somebody who’s bent on conquering Ukraine.

In that same July 12, 2021 article, and again, in an important speech on February 21, 2022, this is three days before the Russians invaded Ukraine, he wrote, “Russia accepts the new geopolitical reality that took shape after the dissolution of the USSR.” He reiterated that same point three days later on February 24, 2022, when he announced that Russia would invade Ukraine. All of these statements are directly at odds with the claim that Putin wanted to conquer Ukraine and incorporate it into a greater Russia.

The Troop Numbers Question

Second, Putin did not have anywhere near enough troops to conquer Ukraine. I estimate that Russia invaded Ukraine with at most 190,000 troops. General Sierski, who as you all know, is now the present commander of the Ukrainian forces, estimates that the Russians invaded Ukraine with 100,000 troops. So John estimates that they invaded with 190,000. Sierski estimates that they invaded with 100,000.

There is no way that a force numbering either 100,000 or 190,000 could conquer, occupy and absorb all of Ukraine into a greater Russia. Consider that when Germany invaded the western half of Poland on September 1, 1939, and you remember as a result of the Von Ribbentrop Molotov Pact, the Soviet Union invaded the Eastern part of Poland and the Germans invaded the Western part. So the Germans only invaded half of Poland.

The Wehrmacht on September 1, 1939, sent 1.5 million troops into Poland. Ukraine is geographically more than three times larger than the western half of Poland. And Ukraine in 2022 had almost twice as many people as Poland did when the Germans invaded.

If we accept Sierski’s estimate that 100,000 Russian troops invaded Ukraine, and again, this is General Sierski speaking, that means Russia had an invasion force that was one-fifteenth the size of the German force that went into Poland. And that small Russian army was invading a country that was much larger than the western half of Poland in terms of both territorial size and population.

One might argue, and of course, often hear this argument, that Russian leaders thought that the Ukrainian military was so small and so outgunned that their army could easily conquer the entire country. But this is not the case. In fact, Putin and his lieutenants were well aware that the United States and its European allies had been arming and training the Ukrainian military since the crisis first broke out in 2014.

Indeed, Moscow’s great fear at the time was that Ukraine was becoming a de facto member of NATO. Moreover, Russian leaders recognize that the Ukrainian army, which was larger than the invasion force. I want to emphasize this. The Ukrainian army was larger than the Russian invasion force. It was armed and trained by NATO, and it was becoming a de facto member of NATO.

They recognized that, that force had been fighting effectively in the Donbas since 2014. They surely understood, the Russians that is, that the Ukrainian military was not a paper tiger that could be defeated quickly and decisively, especially since it had powerful backing from the West. And you remember before the war, the West, especially the United States, made it clear that we would back Ukraine to the hilt if it was invaded by Russia.

Early Negotiations and Diplomatic Efforts

Putin’s aim was to quickly achieve limited territorial gains and force Ukraine to the bargaining table, which is what happened. And this brings me to my third point. Immediately after the war began, Russia, not Ukraine, Russia reached out to Ukraine to start negotiations to end the war and work out a modus vivendi between the two countries. This move is directly at odds with the claim that Putin wanted to conquer Ukraine and make it part of Greater Russia.

Negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow began in Belarus just four days, four days after the Russian invasion. And that Belarus track was eventually replaced by an Israeli as well as an Istanbul track. The available evidence indicates that the Russians were negotiating seriously and were not interested in absorbing Ukrainian territory save for Crimea, which they had annexed in 2014 and possibly the Donbas region.

The negotiations ended when the Ukrainians with prodding from Britain and the United States walked away from the negotiations, which were making good progress at the time. The Russians did not walk away from the negotiations.

Fourth, in the months before the war started, Putin tried to find a diplomatic solution to the brewing crisis. On December 17, 2021, remember, the war begins February 2022, this is December 17, 2021, Putin sends letters to both President Biden and to NATO Chief, Jens Stoltenberg, proposing a solution to the crisis based on a written guarantee that does three things.

It says, number one, Ukraine would not join NATO. Number two, no offensive weapons would be stationed near Russia’s borders. And number three, NATO troops and equipment moved into Eastern Europe since 1997 would be moved back to Western Europe.

Whatever one thinks of the feasibility of reaching a bargain based on Putin’s opening demands, it shows he was trying to avoid war. The United States, on the other hand, refused to negotiate with Putin. It appears it was not interested in avoiding war.

Fifth, this is my fifth and final point. Putting Ukraine aside, there is not a scintilla of evidence that Putin was contemplating conquering any other countries in Eastern Europe. And this is hardly surprising given that the Russian army is not even large enough to overrun all of Ukraine, much less to conquer the Baltic states, Poland, and Romania.

Plus those countries outside of Ukraine are all NATO members, which would almost certainly mean war with the United States and its allies. In sum, while it is widely believed in Europe, and again, I’m sure here in the European Parliament that Putin is an imperialist who has long been determined to conquer all of Ukraine and then conquer additional countries west of Ukraine, virtually all the available evidence is at odds with this perspective.

The Root Causes of the Conflict

In fact, the United States and its European allies provoked the war. This is not to deny, of course, that Russia started the war by invading Ukraine. But the underlying cause of the conflict was the NATO decision to bring Ukraine into the alliance, which virtually all Russian leaders saw as an existential threat that must be eliminated.

But NATO expansion is not the whole problem. This is part of a broader strategy that aims to make Ukraine a Western bulwark on Russia’s border. Bringing Kyiv into the European Union and promoting a color revolution in Ukraine. You all remember the Orange Revolution, which was designed to make Ukraine a pro-Western liberal democracy or the other two prongs of the policy.

So I want to make it clear here. There are three prongs to NATO to the West policy towards Ukraine. One is NATO expansion into Ukraine, two is EU expansion into Ukraine and three is regime change turning Ukraine into a pro-Western liberal democracy. Russian leaders fear all three prongs of this policy, but they fear NATO expansion the most.

As Putin put it, “Russia cannot feel safe, develop and exist while facing a permanent threat from the territory of today’s Ukraine.” In essence, he was not interested in making Ukraine part of Russia. He was interested in making it sure it did not become part of what he labeled “a springboard for Western aggression against Russia.” To deal with this threat, Putin launched a preventive war. This was a preventive war, in my opinion, on February 24, 2022.

Evidence Supporting the NATO Expansion Thesis

Now what’s the basis of the claim that NATO expansion was the principal cause of the Ukraine? What’s the basis on which I make this line of argument?

First, Russian leaders across the board said repeatedly before the war that they considered NATO expansion into Ukraine to be an existential threat that had to be eliminated. Putin made numerous public statements laying out this line of argument before February 24, 2022. Other leaders, including the Defense Minister, the Foreign Minister, the Deputy Foreign Minister and Moscow’s ambassador to Washington also emphasized the centrality of NATO expansion for causing the crisis over Ukraine.

Sergey Lavrov, the Foreign Minister made this point succinctly at a press conference on January 14, 2022. This is approximately one month before the war started. He said, “The key to everything is the guarantee that NATO will not expand eastward.”

Second, the centrality of Russia’s profound fear of Ukraine joining NATO is illustrated by events since the war started. For example, during the Istanbul negotiations, which I was talking about before, Russian leaders made it manifestly clear that Ukraine and the West had to accept permanent neutrality and could not join NATO.

The Ukrainians actually accepted Russia’s demands without serious resistance at Istanbul, surely because they knew that otherwise, it would be impossible to end the war. More recently, on June 14, 2024, this is not this past June, but last June, June 14, June 2024, Putin laid out Russia’s demands for ending the war. One of his core demands was that Kyiv officially state that it is that it abandons its plans to join NATO.

None of this is surprising as Russia has always seen Ukraine and NATO as an existential threat that must be prevented at all costs.

Western Recognition of the Threat

Third, a substantial number of influential and highly regarded individuals in the West recognized before the war that NATO expansion, especially into Ukraine, would be seen by Russian leaders as a mortal threat and eventually would lead to disaster.

William Burns, who was recently Joe Biden’s head of the CIA, but he was the American ambassador to Moscow in April 2008 when the decision was made to bring Ukraine and Georgia into NATO. He wrote a very famous memo that I’m sure some of you are familiar with to then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. This is a quite remarkable memo, and I’m going to quote extensively from it.

“Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all red lines for the Russian elite, not just Putin, in more than 2.5 years of conversations with key Russian players from knuckle draggers in the dark recesses of the Kremlin to Putin’s sharpest liberal critics. I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine and NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russia’s interests.”

“NATO,” he said, “would be seen as throwing down the strategic gauntlet. Today’s Russia will respond. Russian-Ukrainian relations will go into a deep freeze. It will create fertile soil for Russian meddling in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine.” This was written by Bill Burns in 2008.

Burns was not the only Western policymaker in 2008, who understood that bringing Ukraine into NATO was fraught with danger. This is at the Bucharest Summit. This is where the decision is made to bring Ukraine into NATO. Both Angela Merkel, who was then the German Chancellor and French President Nicolas Sarkozy, adamantly opposed moving forward to bring Ukraine into NATO.

And this is what Merkel said about her thinking at the time. This is really truly remarkable. Merkel said, “I was very sure that Putin is not going to just let that happen. From his perspective, that would be a declaration of war.” That’s Angela Merkel speaking. She is saying that the decision that was made in the April 2008 meeting in Bucharest that saying Ukraine would be allowed to come in to NATO would be seen by the Russians as a declaration of war.

The Russian Perspective on NATO

Supporters are bringing Ukraine into NATO sometimes argue that Moscow should not have been concerned about enlargement because NATO is a defensive alliance and poses no threat to Russia. Mike McFaul, who is the American ambassador to Moscow at the time, has told me that he told Putin that on numerous occasions, that Putin had nothing to fear from NATO expansion. It was led by a benign hegemon known as the United States, and NATO is not a threat.

But that is not how Russian leaders think about Ukraine and NATO. And it is what they think that matters. I just want to quickly point out to you. I have a number of friends who deny that NATO expansion into Ukraine is an existential threat. My response to them is it doesn’t matter what you think. All that matters is what the Russians think.

And it’s manifestly clear that the Russians see NATO expansion into Ukraine as an existential threat. And as Angela Merkel said, they will see it as a declaration of war.

In sum, there’s no question that Putin saw Ukraine joining NATO as a mortal threat that could not be allowed and was willing to go to war to prevent it from happening, which he did, of course, in February of 2022.

The Course of the War

Now let me talk a bit about the course of the war, what’s happening in the war. After the Istanbul negotiations failed, this is in April 2022. Remember, the war starts February 22, 2022, and then the negotiations failed by mid-April 2022.

The War of Attrition

The Ukraine conflict turned into a war of attrition, bearing actually marked similarities to World War I on the Western Front. This war, which has been a brutal slugfest, has now been going on for three and a half years. And during that time, as you all know, Russia has formally annexed four Ukrainian oblast in addition to Crimea, which it annexed in 2014.

In effect, Russia has so far annexed about twenty-two percent of Ukraine’s pre-2014 territory. And all of that, of course, is in the Eastern one-fifth of the country.

The West has provided enormous support to Ukraine since the war broke out, everything but directly engaging in the fighting. It’s no accident that Russian leaders think that their country is at war with the West. Nevertheless, as you well know, President Trump is determined to sharply limit America’s role in the war and shift the burden of supporting Ukraine onto Europe’s shoulders.

Now Russia is clearly winning this war, and it’s likely to prevail. And I believe the reason is very simple.

Russia’s Military Advantage

In a war of attrition, each side tries to bleed the other side white, which means that the side that has more soldiers and more firepower is likely to emerge victorious. Russia has a significant advantage on both dimensions.

For example, General Syrskyi says that Russia now has three times more forces engaged in the fight than Ukraine does. And he says that at some points along the front lines, the Ukrainians are outnumbered six to one. So it’s an overall ratio of three to one says Syrskyi. And at some points, it’s six to one.

And in fact, according to numerous reports from the Ukrainian side, the Ukrainians do not have enough soldiers to defend the front lines. They can’t thickly populate the front lines with their combat forces. They have to leave open spaces that the Russians can exploit or penetrate.

In terms of firepower, throughout most of the war, Russia’s advantage in artillery, which is a critically important weapon in attrition warfare, Russia has had an advantage reported to be either three to one, seven to one or ten to one.

Russia also has a huge inventory of highly accurate glide bombs, which they have used with deadly effectiveness against Ukrainian defenses. Kyiv has hardly any glide bombs. While there’s no question that Ukraine has a highly effective drone fleet, which was initially more effective than Russia’s drone fleet, Russia has turned the tables over the past year, and Russia now has an upper hand with drones as well as artillery as well as glide bombs.

Ukraine’s Manpower Crisis

It’s important to emphasize that Kyiv has no viable solution to its manpower problem as it has a much smaller population than Russia, and it is plagued by draft dodging and desertion. Reports are that in October, twenty thousand Ukrainian soldiers deserted from their frontline positions. That is a remarkable number.

Moreover, Russia has a robust industrial base, which produces vast quantities of weaponry, while Ukraine’s industrial base is paltry. To compensate Ukraine depends heavily on the West for weaponry, but Western countries lack the manufacturing capability necessary to keep up with Russian output. To make matters worse, Trump is slowing down the flow of American weaponry to Ukraine.

The bottom line is that Ukraine is badly outmanned, badly outgunned, which is fatal in a war of attrition.

On top of that dire situation on the battlefield, Russia has a huge inventory of missiles, both ballistic missiles and cruise missiles and drones that it uses to strike deep into Ukraine and destroy critical infrastructure and weapons depots. For sure, Kyiv has the capability to hit targets deep inside Russia with its drones, but it has nowhere near the striking power Moscow possesses.

Moreover, striking targets deep inside Russia is going to have little effect on what happens on the battlefield where this war is being settled.

Prospects for Peace

What about the prospects for a peaceful settlement? There’s been much discussion over the course of 2025 about finding a diplomatic settlement to end the war. This conversation is due in good part to President Trump’s promise that he would settle the Ukraine war even before he moved into the White House. And if he didn’t solve it before he moved into the White House, he would settle it shortly after he moved in.

He obviously failed. Indeed, he has not even come close to succeeding. The sad truth is that there is no hope of negotiating a meaningful peace agreement. This war will be settled on the battlefield where the Russians are likely to win an ugly victory.

I’m choosing my words carefully here. They’re going to win an ugly victory that results in a frozen conflict with Russia on one side and Ukraine, Europe and the United States on the other side. Let me explain.

Irreconcilable Differences

Settling the war diplomatically is not possible because the opposing sides have irreconcilable differences. Moscow insists Ukraine must be a neutral country, which means it not only cannot be in NATO, it can’t have meaningful security guarantees from the West. Russians insist on that.

The Russians also demand that Ukraine and the West recognize their annexation of Crimea plus the four oblast that they’ve annexed in Eastern Ukraine. And their third demand is that Kyiv limit the size of its military to the point where it presents no meaningful military threat to Russia.

Unsurprisingly, Europe and especially Ukraine categorically reject these demands. Ukraine refuses to concede any territory to Russia, which you can understand, while Europe and Ukraine continue to push to bring Ukraine into NATO or at least allow the West to give Ukraine meaningful security guarantees. Disarming Ukraine to the point where it satisfies Moscow is also a nonstarter.

There’s no way these opposing positions, the Russian position and the Ukraine plus West position can be reconciled to produce a peace agreement. Thus, the war will be settled on the battlefield.

Although I believe the Russians will win and are close to winning now, the Russians will not win a decisive victory where they end up conquering all of Ukraine. I want to be very clear on that.

Instead, it’s likely to be, as I said, an ugly victory where Russia ends up occupying somewhere between twenty percent to forty percent of pre-2014 Ukraine, while Ukraine ends up as a dysfunctional rump state covering the territory that Russia does not conquer.

Moscow is unlikely to try to conquer all of Ukraine because the Western sixty percent of that country is filled with ethnic Ukrainians who would mightily resist a Russian occupation and turn it into a nightmare for the occupying forces.

All of this is to say that the likely outcome of the Ukraine war is a frozen conflict between a Greater Russia and a rump Ukraine backed by Europe.

Consequences for Ukraine

Let me now explore the likely consequences of the Ukraine war, focusing first on the consequences for Ukraine itself and then on the consequences for relations between Europe and Russia. And then finally, I’ll turn to the likely consequences inside of Europe as well as for transatlantic relations.

Starting with Ukraine. Ukraine has effectively been wrecked. It has already lost a substantial portion of its territory and is likely to lose more land before the fighting stops. Its economy is in tatters with no prospect of recovery in the foreseeable future.

And according to my calculations, it has suffered roughly one million casualties, a staggering number for any country, but certainly for one that is said to be in a demographic death spiral. Russia has paid a significant price as well, but it has suffered nowhere near as much as Ukraine.

Europe will almost certainly remain allied with rump Ukraine for the foreseeable future, given sunk costs and the profound Russophobia that pervades the West. But that continuing relationship between Europe and Ukraine will not work to Kyiv’s advantage for two reasons.

First, it will incentivize Moscow to interfere in Ukraine’s domestic affairs to cause economic and political trouble so that it is not a threat to Russia and is in no position to join either NATO or the EU.

Seeing Europe’s commitment to supporting Kyiv no matter what motivates Russia to conquer as much Ukrainian territory as possible while the war is raging so as to maximize the weakness of the Ukrainian rump state that remains once the conflict is frozen.

In other words, if you’re playing Putin’s hand and you believe the Europeans are going to be deeply committed to Ukraine for the foreseeable future, you have a deep seated interest in grabbing Odessa, grabbing Kharkiv and grabbing all the oblast in between. You want to take forty percent of Ukrainian territory.

You want to do everything you can to wreck Ukraine, and then you want to keep Ukraine weak for the foreseeable future because you understand the Europeans will be supporting the Ukrainians, and they will be interested in causing you Russia trouble.

So the basic point I’m making here is that maintaining close relations with Ukraine is not going to work to Ukraine’s advantage.

Europe-Russia Relations

What about relations between Europe and Russia moving forward? They are likely to be poisonous as far as the eye can see. Europeans and surely the Ukrainians will work to undermine Moscow’s efforts to integrate Ukrainian territories that Russia has annexed as well as look for opportunities to cause the Russians economic and political trouble.

Russia, for its part, will look for opportunities to cause economic and political trouble inside Europe and between Europe and the U.S. Russian leaders will have powerful incentives to fracture the West as much as possible since the West will have its gun sights on Russia. And one does not want to forget that Russia will be working to keep Ukraine dysfunctional while Europe will be working to make it functional.

Relations between Europe and Russia will not only be poisonous, they will also be dangerous. The possibility of war will be ever present.

Six Flash Points

In addition to the risk that war between Ukraine and Russia could restart, there are six other flash points where a war pitting Russia against one or more European countries could break out.

First, consider the Arctic, where the melting ice has opened the door to competition over passageways and resources. Remember that seven of the eight countries that are physically located in the Arctic are NATO members. Russia is the eighth country, which means that it is outnumbered seven to one by NATO countries in that strategically important area.

The second flash point is the Baltic Sea, which is sometimes referred to as a “NATO lake” because it is largely surrounded by countries from the alliance. That waterway, however, is a vital strategic interest to Russia as is Kaliningrad, the Russian enclave in Eastern Europe that is also surrounded by NATO countries.

The fourth flash point is Belarus, which because of its size and location is as strategically important to Russia as Ukraine. The Europeans and the Americans, however, will surely try to install a pro-American or pro-Western government in Minsk after President Lukashenko leaves office and eventually hope to turn Belarus into a pro-Western bulwark on Russia’s borders.

The West is already deeply involved in the politics of Moldova, which not only borders Ukraine, but contains a breakaway region known as Transnistria, which is occupied by Russian troops.

The final flash point is the Black Sea, which is of great strategic importance to both Russia and Ukraine as well as a handful of European countries, which include Bulgaria, Greece, Romania and Turkey. As with the Baltic Sea, there is much potential for trouble in the Black Sea.

All of this is to say that even after Ukraine becomes a frozen conflict, Europe and Russia will continue to have hostile relations in a geopolitical setting filled with trouble spots. In other words, the threat of a major European war will not go away when the fighting in Ukraine stops.

Consequences for Europe

Let me now turn to the consequences of the war for inside of Europe and then turn to its likely effects on the transatlantic relationship.

For starters, it cannot be emphasized enough that a Russian victory in Ukraine, even if it is an ugly victory, as I anticipate, would be a stunning defeat for Europe. Or to put it in slightly different words, it would be a stunning defeat for NATO, which has been deeply involved in the Ukraine conflict since it started. Indeed, the alliance has been committed to defeating Russia since February 2022.

NATO’s defeat will lead to recrimination between member states and inside many of them as well. Who is to blame for this catastrophe will matter greatly to the governing elites in Europe. And surely, there will be a powerful tendency to blame others and not accept responsibility themselves.

The debate over who lost Ukraine will take place in a Europe that is already wracked by fractious politics, both between countries and inside them. In addition to these political fights, some will question the future of NATO, given that it failed to check Russia, the country that most European leaders describe as a mortal threat.

It seems almost certain that NATO will be much weaker after the Ukraine war is shut down than before that war started. Any weakening of NATO will have negative repercussions for the EU. Because as I said earlier, a stable security environment in Europe is essential for the EU to flourish, and NATO is the key to stability in Europe.

Economic Impact

Threats to the EU aside, the great reduction in the flow of gas and oil to Europe since the war started has seriously hurt the major economies of Europe and slowed down growth in the overall Eurozone. There’s good reason to think that economic growth across Europe is a long way from recovering after that war in Ukraine turns into a frozen conflict.

Transatlantic Blame Game

A defeat in Ukraine is also likely to lead to a transatlantic blame game, especially since the Trump administration has refused to support Kyiv as vigorously as the Biden administration and instead pushed the Europeans to assume more of the burden of keeping Ukraine in the fight.

Thus, when the war finally ends with a Russian victory, Trump can accuse the Europeans of not stepping up to the plate, while the European leaders can accuse Trump of bailing out on Ukraine in its greatest moment of need. Of course, Trump’s relations with Europe have long been contentious, so these recriminations will only make a bad situation worse.

# Europe’s Bleak Future: The Ukraine War and NATO’s Uncertain Path

The Future of U.S. Military Presence in Europe

Then there’s the all important question of whether the United States will significantly reduce its military footprint in Europe or maybe even pull all of its combat troops out of Europe. As I emphasized at the start of my talk, independent of the Ukraine war, the historic shift from unipolarity to multipolarity has created a powerful incentive for the United States to pivot to East Asia, which effectively means pivoting away from Europe.

That move alone has the potential to put an end to NATO, which is another way of saying an end to the pacifier in Europe. What has happened in Ukraine since 2022 makes that outcome more likely to repeat. Trump has a deep seated hostility to Europe, especially its leaders, and he will blame them for losing Ukraine.

He has no great affection for NATO and has described the EU as “an enemy created to screw the United States.” That’s Trump talking about the United States. It’s an enemy designed to screw the United States. And he has three point five more years left in office.

Furthermore, the fact that Ukraine lost the war despite enormous support from NATO is likely to lead him, President Trump, to trash the alliance as ineffective and useless. That line of argument will allow him to push Europe to provide for its own security and not free ride on the United States.

In short, it seems likely that the results of the Ukraine war coupled with the spectacular rise of China will eat away at the fabric of the transatlantic relationship in the years ahead, much to the detriment of Europe.

A Disaster That Keeps Giving

I’d like to close now with a few general observations. For starters, the Ukraine war has been a disaster. Indeed, it is a disaster that is almost certain to keep giving in the years ahead. It has had catastrophic consequences for Ukraine. It has poisoned relations between Europe and Russia for the foreseeable future, and it has made Europe a more dangerous place.

It has also caused serious economic and political harm inside Europe and badly damaged transatlantic relations. This calamity raises the inevitable question: who’s responsible for this war? This question will not go away anytime soon. And if anything, is likely to become more prominent over time as the extent of the damage becomes more apparent to more people.

The answer, of course, is that the United States and its European allies are principally responsible. The April 2008 decision to bring Ukraine into NATO, which the West has relentlessly pursued since then, doubling down on this commitment at every opportunity, is the main driving force behind the Ukraine war.

Most European leaders, and I’m sure most people and the various European publics will blame Putin for causing the war and thus for its terrible consequences. But they are wrong. The war could have been avoided if the West had not decided to bring Ukraine into NATO or even if it had backed off from that commitment once the Russians made that their opposition clear.

Had that happened, Ukraine would almost certainly be intact today within its pre-2014 borders, and Europe would be more stable and more prosperous. You just want to think about what I’m saying here. Had we not made the decision to bring Ukraine into NATO in April of 2008 or if once having made that decision, we saw how clear cut Russian opposition was had we backed off, Ukraine would be intact today inside its pre-2014 borders. Crimea would still be part of Ukraine.

And furthermore, Europe would be a more prosperous and more stable place than it is. But that ship has sailed and Europe must now deal with the disastrous results of a series of avoidable blunders. Thank you.

Question and Answer Session

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: Thank you, Professor Mearsheimer, for your very interesting speech and analysis. You now have studies for a round of questions. So raise your hand and it’s different word than a state of the name and organization job title. So we thank you, Professor Mearsheimer, for your very interesting insights. Interesting described what will happen if things continue as they are. But what if you today had the ability to guide Europe right now? The war in Ukraine has shown that Europe’s geopolitical weight has declined significantly. Do you see any chance of restoring that? What would your recommended course of action be in the current situation? I realize this is quite a short question, but the answer can be quite broad.

JOHN MEARSHEIMER: Well, I certainly think from Ukraine’s point of view, and I’ve been arguing for one point years now, from Ukraine’s point of view, the best thing would be to get on an airplane, go to Moscow and work out a deal with Putin, where you accept the fact you have lost those four oblasts plus Crimea, that you can’t be in NATO, you can’t have security guarantees from the West, and you will not build a military that threatens Russia.

And do everything you can if you’re Ukraine to make sure the Russians don’t take much more territory. If I’m a Ukrainian, my greatest fear is they’re going to take Odessa, they’re going to take Kharkiv and a handful of other oblast as well. And if I’m a Ukrainian, I want to prevent that.

Furthermore, if I’m a Ukrainian, I don’t want this war to go on because the end result is that more Ukrainians are going to die. I have been arguing for a long time that this is the smart strategy. Now people will say, is this a good outcome? The one that I’m describing? No, it’s a terrible outcome.

What I’m suggesting Ukraine do and what I’m suggesting the European support the Ukrainians in pursuing is a terrible outcome. But it is the least bad outcome because the alternative is the war continues, the Russians take more territory and they do they kill more Ukrainians, right? And they have a greater incentive to turn Ukraine into a dysfunctional rump state, right?

So I think the best alternative is to do that and for the Europeans to support them. But it is almost impossible for me to sell this argument. Hardly anybody wants to hear this argument. I find this hard to understand because I think it’s just commonsensical. I think when you look at what’s actually happening in the war, where things are headed, it makes sense to do what I said.

And there are some Ukrainians, by the way, who accept this line of argument, but they’re greatly outnumbered by the Zelenskyys of the world. And certainly, here in Europe, that kind of argument doesn’t work. So I think the war will go on, and it will end up as a frozen conflict.

At some point, the Ukrainian military forces on the front line will be unable to continue the fight. And then the only interesting question is how much territory does Ukraine lose. And then because of Europe’s deep commitment to remaining attached to Ukraine and bringing Ukraine into the alliance or giving Ukraine security guarantees, I think that for as far as the eye can see, you’re going have big trouble in Ukraine and in terms of European Russian relations. All right.

Parallels with the Cuban Missile Crisis

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Next question in the back. Professor, would it be right if I would call this moment in 2008 the fixed payment of Russia? I mean, the Canada crisis, the Cuba crisis. Is that to be compared or is it different?

JOHN MEARSHEIMER: Well, the Cuban Missile Crisis bears a marked similarity to what happened in Ukraine in one very important way. You all know that we and the United States have the Monroe Doctrine. And the Monroe Doctrine says that no distant great power is allowed to come into the Western military into the Western Hemisphere and put military forces its military forces in the Western Hemisphere.

And if you think about what happened in 1962, the Soviet Union put missiles in Cuba, right next to the United States. And by the way, when the deal was cut between Khrushchev and Kennedy, Kennedy insisted, of course, that the missiles be taken out of Cuba, which is what happened. And the quid pro quo was that Khrushchev insisted that we take the Jupiter missiles out of Turkey because the Jupiter missiles in Turkey were right on the Soviet Union’s border.

The fact is that great powers do not like other great powers coming great distances up to their doorstep. And what happened with regard to Ukraine is analogous to what happened in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Just to take this a step further because it’s very important to understand what happened in the Cold War with regard to missiles in Europe. It’s quite clear that the Reagan administration was pursuing a first strike capability in the 1980s. You all know President Reagan got elected in 1980, took office in 1981. He had an administration that was filled with hawks.

Most of you probably don’t appreciate this, but at the time, the Soviet Union and the United States had massive nuclear arsenals. And there was no way they could use those nuclear arsenals to fight a nuclear war without basically ending life on earth because of nuclear winter and assorted other phenomena, right?

So what the United States was very interested in doing was launching a decapitating strike. We wanted to be able to decapitate the Soviet arsenal. It was a splendid first strike in the form of decapitation. And many people viewed the Pershing and ground launched cruise missiles that we put in Europe as excellent decapitating weapons. These are missiles that are right up on the Soviet Union’s doorstep, okay?

Soviet Union went away, replaced by Russia. What the Russians really feared was that we would put missiles in Ukraine. And those missiles in Ukraine could be used for a decapitation strike. This is why the Russians were so upset with the ballistic missile defense systems that we put in Poland and in Romania after the Cold War ended.

You understand, after the Cold War ended, the United States put ballistic missile defense systems in Ukraine and Poland. But the problem is that those defensive systems can be used for offensive purposes. In other words, you can put missiles into those defensive systems that can strike Russia and could be used for a decapitation strategy.

So when you talk about bringing an alliance, right, that was a mortal enemy of the Soviet Union up to Russia’s doorstep in Ukraine and putting missiles there that might be used for decapitation, the parallels with the Cuban Missile Crisis are quite marked. And you know how we reacted in the Cuban Missile Crisis. And unsurprisingly, the Soviets, excuse me, the Russians reacted the same way.

The Origins of NATO Expansion

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Next question, and please state your name before question. Hans Leuhof, Potent for Germany. It was hubris to some extent, but that doesn’t go deep enough.

JOHN MEARSHEIMER: NATO expansion became a serious issue when Bill Clinton moved into the White House. Bill Clinton won the election in 1992, and he moved into the White House in January 1993. And I believe the decision to expand NATO was finally made in late 1994, okay? And the first tranche of expansion was in 1999. That’s when Poland, Czech Republic and Hungary come in. And then the second big tranche was 2004.

Now it’s very important to understand two things. One is that Russia was remarkably weak in the 1990s and even in the early 2000s. Vladimir Putin resurrected the Russians from the dead. So you want to understand that when we started NATO expansion in the ’90s, it was not designed to contain Russia.

Given the world that we live in today, I’m sure lots of people think that NATO expansion, when it started in 1994, was designed to contain Russia, that Russia was seen as a threat. That is not true. What was driving NATO expansion, this gets to my second point, is that we were the Unipol. We’re the only great power on the planet.

And you all understand in a world where we’re the only great power on the planet, there is no great power politics because there’s only one great power. So for the first time in our history, we were in a position to pursue a liberal foreign policy. And we pursued a policy that many people call liberal hegemony.

We pursued a foreign policy that was designed to remake the world in America’s image, and the Europeans went along with us. They were our sidekicks in this enterprise. You want to understand, I talked about the Chinese threat today. We helped create that threat because we helped China to grow more and more powerful economically.

And a realist like me said at the time, China is going to translate that economic power into military power, and it’s going to try to dominate East Asia to the disadvantage of the United States. Virtually, everybody I talked to said, “John, you are a dinosaur. Your realist view of international politics is outdated. We live in a new world. China is going to grow economically. It’s going to get hooked on capitalism. It’s going to get integrated into institutions like the WTO.”

“It’s eventually going to turn into a liberal democracy like the Asian Tigers did, and we’re going to live happily ever after because China is going to look like us, and we’re the good guys. And if they look like us, the world is filled with good guys, we live happily ever after.” That was the belief. That was liberal hegemony applied to China.

Liberal Hegemony and NATO Expansion

Now how does that apply to NATO expansion? What we were doing with NATO expansion, it’s a liberal policy. It’s not designed to contain Russia. We’re taking those institutions like NATO and the EU, and we’re expanding or enlarging those institutions, we’re moving them eastward, bringing in new members, they will become responsible stakeholders.

Furthermore, we’re making sure they’re all hooked on capitalism, right? Making them economically interdependent. And if everybody is economically interdependent, nobody is going to fight because who would want to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs, the whole argument.

So institutions are spreading eastward, economic interdependence is spreading eastward. And then very importantly, the velvet revolutions, right, or the color revolutions, the orange revolution, the rose revolution. We’re going to promote revolutions in Eastern Europe that are designed to turn those countries into pro Western liberal democracies. And if you create a world that’s filled with liberal democracies, you live happily ever after.

The End of History and Liberal Democracy

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: For many of the younger people in the audience, you’re going to think this is hard to believe because in 2025, it makes no sense. But I just want to say a word or two about Frank Fukuyama’s very famous article, “The End of History,” which you should all go read if you haven’t read it. It’s a terribly important argument because it is the software that was in the heads of European elites and American elites and is still in the heads of many European and American elites.

Frank Fukuyama’s argument was that liberal democracy is the future. We liberal democracies have the wind at our back, and there are going to be more and more liberal democracies around the world. And the end result is peace. And in fact, he says at the end of the article that the biggest problem we face going forward is boredom. Boredom. Just think about that. War is off the table.

And it’s an argument for creating democracy, spreading institutions and spreading capitalism and fostering economic independence. That’s what was motivating us. We were not interested in screwing the Russians. Clinton and company in the 1990s understood that the Russians were going to protest. There’s no question about that.

Lots of the planning documents are now available. The Clinton people understood that the Russians were adamantly opposed, but they thought they could buy the Russians off because they thought we were a benign hegemon, right? That’s what they thought was going on here.

Color Revolutions and Russia

And by the way, just on talking about the color revolutions, we wanted to spread a color revolution to Russia as well. There’s an article in The New Yorker about Mike McFaul, who was the U.S. Ambassador to Russia, as I was telling you before, at the time when the Ukraine crisis broke out in 2014.

But you should read, you can Google it, The New Yorker article on Mike McFaul. He was basically trying to foster a color revolution inside of Russia when he was the U.S. Ambassador to Russia. Needless to say, this made the Russians super angry, and they insisted that he’d be withdrawn as ambassador, right? But it just gives you a sense of what’s going on here.

So it was the fact that we had this deeply embedded liberal foreign policy that got this train out of the station. And it covered the first tranche, 1999, the second tranche, 2004. And then it was impossible to stop. Once NATO expansion started, it was just impossible to stop.

And it’s quite amazing that nobody in the West, except for maybe Trump on occasion, says no more NATO expansion, right? Europeans would be saying at this point in time, we’ve had enough NATO expansion. This has led to enough trouble. We have got to get our house in order. The last thing we want to do is keep provoking the Russians because it’s not going to work to our benefit here in Europe. But nobody says that. I shouldn’t say nobody. Hardly anybody says that. That’s certainly not the mainstream view.

Liberal Hegemony and Its Failures

So I think it’s actually the pursuit of a liberal foreign policy. And by the way, just one more point on this. I talked about engagement with China, how foolish that was. That’s liberal hegemony. Second example, expansion of NATO, expansion of the EU, color revolutions, Eastern Europe. That’s the second example.

The third example is the Middle East, the Bush Doctrine. The Bush Doctrine was all about democratizing the Middle East. Again, most people have forgot that. We thought we were going to go into Iraq, knock Iraq off, then we’ll maybe do Syria, maybe we’ll do Iran next, go in, knock that regime off, going to turn it into a liberal democracy, right?

It didn’t work out. None of this worked out. The Bush Doctrine, it failed. It crashed and burned in Iraq. China, we created a peer competitor. I’m not sure it’s a peer competitor. It may surpass us at one point in the not too distant future, right? And then the whole subject of NATO expansion.

This was a thoroughly liberal foreign policy, and it comes out of unipolarity. It comes out of the fact, again, once you go to a world where you have one great power, great power politics by definition is taken off the table. That means that people like me, realists who think of the world in balance of power terms are going to be put in the closet. They’re going to lock the door and keep me there. And the liberals are going to dominate, right, which is exactly what happened.

The Transition to Multipolarity

And now the world has changed. This is the transition, which I think was reflected in Tom’s comments and in John’s presentation, going from unipolarity to multipolarity really matters. And that’s the world we’re in, and it’s not going away.

Okay. Next question.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Thank you, professor. It’s a real pleasure to hear from you. Reading your book, then it was also books and articles and Mearsheimer’s and others. So it’s a real pleasure. But allow me to, using the offensive realism, I think that’s what NATO did after the end of the Cold War. So they, NATO took advantage of the victory in the war, of Russia’s weakness to enlarge to Eastern Europe. So it makes sense. Offensive realism perspective, it’s rational.

And they use the power they have or need to use the power they have to enlarge to, so using the Russian weakness, to enlarge to Eastern Europe. And during that, they used power in a way to enlarge their outlook, but also to, and I think you said that containment is not a good concept to explain what happened. The deterrence is, and even you wrote that in an article about the nuclear arms, Ukrainian nuclear arms as an important way to contain, to deterrence of Russia.

So trying to be more simple. I’m not sure if it’s because Ukraine is near to NATO to get to what started. But because Ukraine is not in NATO. Because if it was in NATO like the Baltic States or others, we don’t see that in the Baltic states. So I’m not sure of what I mean, just reflecting about this issue.

But I think if we, the problem is that we will not go to until the end because if they were in NATO, I’m not sure if the ratio will be what they did. So the question for you is, do you think that the start of the Ukraine war was not because of NATO enlargement, but because NATO didn’t enlarge?

NATO Membership and Nuclear Weapons

JOHN MEARSHEIMER: Okay. Three points. I think there’s no question if Ukraine was in NATO that the Russians would not have invaded, but Ukraine was not in NATO.

Second point is, I don’t know how many of you know this, but I wrote a piece in 1993, it was in Foreign Affairs, that said Ukraine should keep its nuclear weapons. I don’t know how many of you know this, when the Soviet Union broke apart, four parts or four of the new countries had nuclear weapons: Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus and Ukraine.

Belarus and Kazakhstan gave up their nuclear weapons, but Ukraine gave a lot of thought to keeping their nuclear weapons. And I wrote a piece that said Ukraine should keep its nuclear weapons because it might need them for a rainy day when the Russians came knocking. And of course, apropos my response to this gentleman here, everybody thought that I was crazy, right?

And Bill Clinton, in particular, has recently said that, and he, of course, Bill Clinton was responsible for making the Ukrainians give up their nuclear weapons. He said that he made a mistake, Clinton did, forcing Ukraine to give up its nuclear weapons.

Offensive Realism and NATO Expansion

But I want to deal with the heart and soul of your question, which is directly opposite the argument that this gentleman made, right, or at least my response to this gentleman. What you’re saying is that NATO expansion may have caused the war, but it was done according to the dictates of my theory. NATO expansion is consistent with my theory. It wasn’t a liberal foreign policy, as I said to this gentleman, as he’s saying.

A number of people make this argument, by the way, and they say that I should adopt this argument because it makes my theory more powerful. I’m conceding to you that my theory didn’t really matter. They locked me in the closet. He’s saying, no, no, no, they acted according to your theory.

Let me just make a couple of points. One is my theory says that you can only be a regional hegemon, right? You cannot be a global hegemon. But in other regions of the world, all you want to do is make sure there’s no other regional hegemon. That’s my Imperial Germany, Imperial Japan, Nazi Germany, Soviet Union argument, okay?

And Russia in the 1990s was not a potential regional hegemon. And as you know, I said today, it’s not a potential regional hegemon. It’s just too weak, right? So according to a strict interpretation of my theory, we actually should have gotten out of Europe, okay? Because there’s no potential regional hegemon. We were Godzilla, we could go home. That’s point one.

But point two is my theory says states should maximize their relative power. And it’s a theory that says you should take advantage of other states at every turn. The name of the game in a system where there’s no higher authority and you have to take care of yourself is to be as powerful as possible. And therefore, you look to take advantage of other sides. This is consistent with what you’re saying.

But it doesn’t call for doing stupid things. And one could argue, even let’s say my theory applies. We’re looking for opportunities. Russia is weak. Let’s begin to push. The problem that you face is that there’s going to be a blowback.

Now the counter to that is we got away with the first tranche, 1999. We got away with it. We got away with the second tranche, 2004. But then comes 2008, that’s the Bucharest decision. The argument would be, if you’re really smart, stop there. You’ve gotten really quite far, right? Two big tranches of expansion, right?

Ukraine and Georgia, it’s a bridge too far or two bridges too far. And you all understand the April 2008 decision said bring in Ukraine, bring in Georgia. And in August of 2008, there was a war over Georgia, right? That should have been the first harbinger of trouble coming on Ukraine.

And you could say a good offensive realist like me should have pushed NATO expansion, right? But should have been well aware that you’re feeling your way around in the dark. But when you run into resistance, stop there. But again, my argument is that there’s no potential hegemon, therefore, no need to really contain the Russians.

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: I think I speak also for many of my colleagues who are here in high number from BASF Group, if I say thank you very much, Tom. Thank you very much, Anders, from the Patriots Foundation that you’ve organized this fantastic event.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Professor Mearsheimer, the question, you name all the negative consequences of the war. You said also that the U.S. were very aware of what is coming when the war will stop. But you didn’t say who really profit of this war. You know, we are in a situation people saying the US, they caused this war, but I don’t think this is in the interest. So who, name the elephant in the room. Who is your question about this?

The Path to War: 2008-2022

JOHN MEARSHEIMER: Yes. Well, let me just say a few more words about how I see it developing the conflict. 2008 is the decision to bring Ukraine into NATO, okay? And the Georgia war happens a few months later. We don’t back off. We continue to push and push. And then the crisis breaks out in February 2014, okay? That’s when the Ukraine crisis breaks out.

The crisis starts in 2014. The war is eight years later, 2022, February 2014. Okay. What’s going on here all along is that we think we could shove NATO expansion down their throat. We think that they complained, the Russians complained bitterly about the 1999 tranche. They complained bitterly about the 2004 tranche, but we just pushed it down their throat. We think that that’s what we’ll do in 2008, okay?

And then when the crisis breaks out in 2014, we don’t back off, right? Between 2008 and 2014, sorry, 2014 when the crisis breaks out and the eight years in between when the war breaks out, we don’t back off. And as I said to you in my formal comments, what’s really amazing is the Americans who are saying that war is likely before it happens, before February 24th, 2022.

The Americans are saying loudly and clearly, war is going to break out. Putin’s going to invade Ukraine. And the Americans are complaining that the Ukrainians won’t take that argument seriously. Yet we do nothing. We do nothing to prevent the war. No diplomacy. And then when the war starts, we are the ones who encourage the Ukrainians to walk away.

So you say to yourself, what’s going on here, right? Really, what’s happening? We thought we could defeat the Russians, as I said. That’s why we didn’t back off.

Putin’s Growing Resistance

So I think what’s happening here is that when Putin comes to power in 2000, all right, and you ramp forward up to 2014, certainly up to 2022, the Russians are beginning to contest the West in really serious ways over that time period.

The first big piece of evidence of how angry Putin is at us is the annual security conference in Munich, 2007. Go back and read Putin’s speech, 2007. Then 2008 is the NATO decision on Georgia and Ukraine. And then you get the Georgia war in 2008, then you get the crisis in 2014.

Now nobody thought that we were going to get a war. I shouldn’t, that’s too strong. The people who were pushing this train down the tracks did not think we’re going to get a war. And then when they thought they’d get a war, they thought we would win like that.

The American Belief in Military Power

And I think that it wasn’t like the military industrial complex was pushing it or there were sort of set of economic or political incentives to do that. The United States is filled with people who believe in the mailed fist. And they believe that the United States is an incredibly powerful country that can use its mailed fist to get its way.

This is especially true of the neoconservatives, who are very powerful element in the decision making process in the United States. This is why we didn’t back off, right? We just thought we would win, and it would be relatively cost free.

And from an American point of view, by 2022, remember, we’re in a multipolar world. Just think about this. We’re in a multipolar world starting about 2017. So the Ukraine crisis breaks out in 2014. That’s in the unipolar world. The war is 2022.

By the time the war comes, Russia is now a great power. Putin has resurrected it from the dead. So what we think we can do is we could defeat the Russians and knock them out of the ranks of the great powers. That’s our basic thinking at the time.

European Acquiescence to American Policy

And the Europeans go along with this. The Europeans used to offer resistance to the Americans. When I was young, there are people like Helmut Schmidt, who was a real tough cookie, as my mother would say. And he’d stand up to the Americans. You all remember Charles de Gaulle. And there were all sorts of other leaders, either Conrad Adenauer and so forth and so on.

The Europeans were willing to argue with the Americans to put up resistance. And this was true even in the Iraq War in 2003, as I’m sure you remember. The French and the Germans were opposed to the Iraq War. But something happened after that. And the Europeans reached a point where they were just incapable of putting up any resistance to the Americans. And in fact, they became cheerleaders.

So when it came to the 2008 decision and what happens moving forward, the Europeans just went along with the Americans. And the Americans are addicted to war. You all understand the United States is addicted to war. We believe that the mailed fist can solve almost every problem.

This is like the Israelis. The Israelis and the Americans, they don’t believe that there’s a political problem out there that can’t be solved with military force. My view is most political problems can only be solved with a heavy dose of political settlement or political calculations, not just military calculations.

But I think that’s basically what drove the train here. The belief that we could get away with it, there was going to be no costs, right, just benefits. And that didn’t turn out to be the case.

As I said in the very beginning, I think most Europeans had no idea we would be where we are today, certainly in the 1990s. But even in the run up to the Ukraine war, right? There’s nobody, I shouldn’t say nobody, there’s hardly anybody who was saying, “Oh my God, this is a disastrous decision. We’re going to get ourselves in real trouble.”

Closing Remarks from Patriots for Europe Foundation

UNIDENTIFIED SPEAKER: Unfortunately, thank you very much. The Patriots for Europe Foundation is the European think tank that is ready to discuss many of the subjects deemed taboo in the European Union. And today’s conference, today’s speech is no different. Thank you very much, Professor Mearsheimer, for that.

The war in Ukraine is the most severe war that the European continent has seen in decades. The policy of the EU and its member states with regards to the war has had a major impact on our security, our economy, and the outcome will largely determine the future of Europe.

The gravity of this situation, its impact on our lives should warrant in-depth discussions like the one today. The EU has adopted almost twenty sanctions packages against Russia in hope of stopping the war. Sanctions have failed to deliver what leaders have promised. As an honest assessment of previous packages, before a new one being adopted never actually took place until this day.

The Failure of EU Strategy

EU leaders also failed to convince non-Western countries to sign up to sanctions. EU elites blindly followed the US’s Ukraine policy pushed by the Biden administration, as professor you have just mentioned. Despite the fact that our economy, our military, our strength and our weaknesses are radically different from that of the United States. The economic burden and therefore has also been much greater on Europe.

The Patriots Foundation organized an event in September to do just that, to talk about the cost of the war and potentially the membership of Ukraine in the EU. The impact of our energy security, the impact on our energy security is impossible to estimate accurately at this moment, but we have talked about the impact on our farmers, on our agriculture and on our budget and, as I said, generally, the cost of EU membership of Ukraine.

With Europe’s high dependence on energy imports, European energy prices make European industry uncompetitive compared to US and Chinese counterparts. Europeans have their greatest interest in restoring peace in Europe.

I come from Hungary, and Hungarians are amazed that Prime Minister Orban’s efforts for a peace deal or ceasefire in Ukraine are met with enormous hostility here in Brussels and many European capitals. If we just think about the last planned recession of the European Parliament, a potential Budapest summit was also on the agenda and heavily criticized by many.

Most leaders in fact categorically refuse to engage in diplomacy and expect others to conclude the war in Ukraine in a way that benefits Europe, which is insane. It’s foolish and totally unrealistic. Europe simply lacks a coherent and realistic strategy for its own security and future. No one will defend European interests if we don’t.

Appreciation for Realist Analysis

Today, it was an honor, Professor Mearsheimer, to have you with us. Most often, you describe yourself as a realist, someone who analyzes global politics based on power relationships as opposed to the ideological approach we hear most often from politicians and mainstream media. Thank you, professor, because you have not failed us.

Thank you, professor, for accepting our invitation. Thank you for your honest analysis and debate provoking thoughts here today. And I’m glad that so many of you accepted our invitation. It shows that Europeans want to know more and hear more than emotionally charged one-liners from EU leaders.

Would like to thank also my friend, Tom Pond Andrzejka, for taking the initiative on inviting Professor Mearsheimer. I think it was a very, very fruitful event. It was a very thought provoking event.

Learning from History

And as many have asked during the Q and A session, why did this happen? And of course, everyone has their explanations and it’s very important to understand why this war happened and why it keeps raging. It came to my mind that there was an episode many of you might know from South Park called “Captain Hindsight” with a character who always went to a disaster struck area and said what people should have done differently to avoid it.