Read the full transcript of Professor Sarah Paine’s lecture series titled “How Mao Conquered China” Episode 3, followed by Q&A on Dwarkesh Podcast, [Jan 30, 2025].

TRANSCRIPT:

Mao’s Historical Significance

SARAH PAINE: One of the most important figures of Chinese history of any century, Mao is the military genius who puts Humpty Dumpty back together again. He is also the most brilliant psychopath in human history. That’s Taiwan’s problem to this day. They are a rebuke to everything the Communist Party is. How embarrassing.

The losers of the war have won the peace and put you to shame for how incompetently brutal you are. The Communists lose ninety-five percent of their forces. Decimate means to lose ten percent. Losing ninety-five percent, I think you need a whole new verb. Forty million Chinese starve to death.

For those of you who think the Chinese are all great long-term strategists, you need to ponder these numbers. How is it possible to kill so many of your own? What I’m about to say are my ideas. They don’t necessarily represent those of the US government, US Navy Department, the US Department of Defense, or the Naval War College. You got that clear?

Complain to me if you’ve problems. Alright. I’m going to talk about Mao. He’s an incredibly consequential figure. He’s, for the twentieth century, he’s one of the most consequential political or military figures.

And he’s also one of the most important figures in Chinese history of any century, and he’s also a terribly significant military and political theorist. And this is not an endorsement of Mao. It is rather just an accurate description of his global and enduring importance. Think about China. Historically, it’s represented, I don’t know, a third of the world’s population, a third of the world’s trade.

Mao’s Theories and Influence

That’s a big slice of humanity.

This presentation is based on the first eight volumes of Stuart Schram’s collected works of Mao. What Schram did is he compared Mao’s complete works as published in the nineteen fifties to whatever he could find as the earliest version of whatever it was, and then he reinserted whatever had been cut in italics. So tonight, watch the italics. And Mao didn’t put all of his best ideas in one place. He scattered them all over the place.

And so what I’ve done is come for you all, prepared like a jigsaw puzzle of all of these different ideas. And then in order to make it comprehensible to you of all these random little tidbits, you have to have like a coat rack to hang all the hangers, and that’s called a simple framework, and I’ll get there. But in your own lives, when you’ve got all kinds of complicated things to transmit to others, you can look at what I’m doing tonight, and you can do it for other things as well. So here we go with good old Mao. And, oh, by the way, a lot of those eight thousand, seven thousand pages weren’t that interesting.

Major Military Theorists

So in a way, you owe me. These are major military theorists. Just to run you through them.

Clausewitz is the West’s major military theorist of bilateral conventional land warfare. Sun Tzu is Han civilization’s great theorist of how you maintain power in a continental empire, multilateral world using coercion and deception. The two fellows on the right are maritime theorists. In a way, they’re writing the missing chapters of Clausewitz that doesn’t talk about naval warfare at all. The top one is Alfred Thayer Mahan, the Naval War College’s finest.

And what he’s writing about are the prerequisites for and strategic policy possibilities for maritime power. And the Britain underneath him there, Sir Julian Corbett, is writing about how a maritime power, i.e. Britain, can defeat a continental power, i.e. Germany or France. But all of them are writing about warfare between states, and Mao is a different event. Mao has to do with triangle building. The term triangle building comes from Clausewitz.

Mao’s Triangle Building

Clausewitz has this nice little passage here where he’s talking about these abstractions, passion, creativity, and rationality as being mainly, but not exclusively, associated respectively with the people, military, and government. A state has full up military and civil institutions that have some connection to their people. But an insurgent is going to be building these things from the ground up. So that’s what Mao is doing, is he’s actually taking over the host from within by building a shadow government and eventually taking power. And many of the decolonizing world after World War II were really sick of the West.

They’ve been colonized. Didn’t want to hear anything about them. But it seemed as if the Soviets or the Chinese perhaps offered a better model, the communist. And many thought that the Chinese, Mao, offered the better model. Why?

Because the decolonizing parts of the world were also agricultural and underdeveloped, unlike Russia, which had quite a military, excuse me, an industrial base. And so they thought Mao was the more relevant guy.

Mao’s Victory and Social Revolution

Here’s Mao at his iconic moment. He’s proclaiming the victory of the communists in the Chinese civil war.

China had been a broken state basically since 1911 when the last dynasty had fallen and the country had broken out into a multilateral civil war that he eventually wins. And I’m going to be talking tonight about Mao’s theories in the from the 1920s and 1930s when he had the time to write, but there’s a lot more to Mao than just that. He had quite a track record. Once he won the civil war, he imposed a social revolution. What’s that?

It’s more than a political revolution. You’re not just replacing the government. You’re going to wipe out entire social classes. And I don’t mean then, hey. Here’s your one way ticket out of here kind of way.

No. No. Social revolution is here’s a mass grave, dig it, and then you’re in it, kind of way. So if you look at these statistics of Chinese deaths in many of their wars, and this is for much of the Maoist period, I think it’s ’45 to ’75, What you’ll notice, the figures in white, I believe, are civilian deaths, not military deaths, and it gets really quite ugly. There are more Chinese civilian deaths here than all deaths in World War II.

The Great Famine

And then for those of you who think the Chinese are all great long-term strategists, you need to ponder these numbers. How is it possible to kill so many of your own? That’s generally not a mark of good strategy. Moreover, most of them died during the great famine, which was the only nationwide famine in Chinese history. Why?

Because it’s not caused by the weather. It’s caused by policies set in Beijing. During the great leap forward, Mao put all the peasants on communes. That meant the party was in control of the food supply, i.e. who lives and who dies. You don’t get a meal. You’re very dead. In addition, he decentralized industry, and you can see these backyard furnaces pictured here. As a result of this, production collapses, agriculture and industrial, but Mao keeps exporting food.

Why? Because that’s his pocket change. That is a major source of government income if he wants to be able to do anything. So they keep exporting food. As a result, forty million Chinese starve to death, primarily in rural areas and disproportionately peasant girls, the least valued members of society.

The statistic of forty million deaths comes from this book by Yang Jisheng, who’s written the definitive work. The English translation is about one volume. The Chinese original is three. Yang worked as a journalist for many years, which gave him access to provincial archives where he surreptitiously investigated the statistics of people who are starving to death, including his father, for whom he wrote this book to serve as an eternal tombstone. So on the one hand, Mao is the military genius who puts Humpty Dumpty back together again when nobody else could and they tried for the previous forty years.

Mao’s Contradictory Legacy

On the other hand, he is the psychopath incapable of running an economy in peacetime. Yet many Chinese revere him as a national hero. Why? Because in their minds, certainly of the Han, the preponderant group in China, one of the key things that their country should and must be is a great power. And now by reunifying China under the banner of communism and then fighting the coalition of all the major capitalist powers to a stalemate in the Korean War or their mind a victory, that constitutes ending what they consider the era of humiliations that started in the mid nineteenth centuries and end with the communist revolution.

So he’s a hero at home.

The Context of Mao’s Wars

To understand Mao’s theories, I need to put it in the context of the wars that he fought. So in 1911, Qing dynasty collapses. The country shatters into a multilateral warfare among warlords of these provincial leaders.

And on this map, you can see the different colors and shadings. Those are different warlord areas. But the nationalist party and the communist party form a united front in 1923 in order to eliminate these warlords. And so, Chiang Kai-shek, who’s the head of the nationalist party, generalissimo, not just the general, He is the man who’s leading the northern expedition to fight off all the warlords, except he stops midway near his power base in Shanghai, and he turns on the communists, massacres them in droves. This is the white terror.

Why? Because he thinks that while he’s away fighting, they’re trying to take over his government. He’s correct. So he keeps on moving there. There’s a nominal unification of China under nationalist rule when this takes place.

The Long March and Japanese Invasion

In addition, once he’s done with that, then he wants to eliminate the communists for good. And so he runs a series of five encirclement campaigns around their base areas that are scattered in South China. The primary base area, base area is also called a Soviet, is the Jiangxi Soviet. And on the fifth encirclement campaign, Chiang Kai-shek is finally successful, and he sends them off on the long march up to way up north in desolate Yanan. Long march is a real misnomer. It’s the long route, and the communists lose ninety-five percent of their forces.

I believe in English, decimate means to lose ten percent. Losing ninety-five percent, I think you need a whole new verb for what’s happened to you. But Chiang Kai-shek doesn’t wipe them out because he’s suffering from divided attentions. When the west did the original, was it both the United States and Europe? The United States does its original America first thing with a Hawley-Smoot tariff, putting tariffs up to historic highs, then everybody, of course, retaliates. And now everybody’s got high tariffs. Well, here’s trade dependent Japan that’s always cooperated with everybody, and suddenly they’re toast. And so their solution is autarky, and they need an empire large enough to be autarkic. And so then that’s when they invade Manchuria in 1931.

World War II in Asia

So Chiang Kai-shek has all of a sudden lost this area from China that’s greater than Germany and France combined. It’s a mess. And so he has he’s trying to balance what to do about Japanese versus communists. The Japanese don’t quit with Manchuria. They stabilize the place.

They make massive infrastructure developments. They transform it into the most developed part of Asia outside of the home islands, but they keep on going. And it gets so bad that the communists and the nationalists form a second united front because they’re facing this lethal threat called Japan. And they organized that in December 1936 in what’s known as the Xi’an incident, and the Japanese react viscerally because they look at it, the nationalists have gone over to the dark side because they’ve joined up with the communists. And this is when the Japanese escalate in 1937, go down the Chinese coast, up the Yangtze River.

And well, but they then they wind up stalemating. Once they get beyond the Chinese railway system, which isn’t that great in this period, the Japanese can’t stabilize the place, the Soviets start adding more aid, and we add more aid. It’s a mess. So the Japanese decide they’re going to cut Western aid to the Chinese, and that’s where Pearl Harbor comes in. That’s what the attack of Pearl Harbor is all about, is telling Americans to stay out of Asia, which, of course, you know, we did just the opposite.

And then the Nazis interpret their alliance with the Japanese broadly to declare war on the United States. So when that happens, you have a regional war that had already been going on over Poland, in Europe, and this other war that had been going on since ’31 in Asia, they unify into a global world war. Mao understood that he was dealing with three layers of warfare and nested wars, that he was fighting a civil war against the nationalists within a regional war against Japan, and then after Pearl Harbor, there’s going to be a global war that will eventually morph into a global cold war.

Most of his writings are written before Pearl Harbor, so he’s going to focus on the first two layers of what’s going on here. So after World War II is over, Mao goes after the nationalists full bore, and the Japanese have already very much weakened the nationalists, and Chiang Kai-shek now wins the civil war.

A Framework for Understanding Mao

These are the wars. Now I promised you a simple framework. Here’s the simple framework. Simple framework should have three to five things, because that’s all about any of us could really handle on short notice.

And so I got four here, and I’m going to use Clausewitz’s definition of great leadership to analyze Mao. According to Clausewitz, “In a general, two qualities are indispensable. First is an intellect, that even in the darkest hour and Mao had many of those retains some glimmering of inner light, which leads to truth and second, the courage to follow that faint light wherever it may lead.” The first of these qualities is described by the French term “coup d’oeil.” “Coup” is a glance, “oeil” is an eye, taking in a situation with a glance of an eye.

Mao the Propagandist

And the second is determination. Well, Mao had these things in myriad areas. I’m going to first discuss Mao the propagandist. That’s how he starts out. And then I’ve got what I say here is Mao the social scientist. But what he was really good at is data collection and analysis. He truly understood the countryside because he collected all sorts of data about it and analyzed it. And then I will go on to Mao, the operational military leader, winning and fighting battles. And then at the end, I’ll talk about Mao, the grand strategist, integrating all elements of national power. So that’s my game plan.

Mao began his public service career as a propagandist. And if you look at his early biography, he’s born in 1893 to a prosperous, but not particularly well educated father who tilled his own land. Mao hated his father. And he hated farming, so he left as soon as possible.

After the 1911 revolution for a little while, he worked as a soldier, didn’t like that. He joined and then dropped out of a series of vocational schools. He tried being a merchant, a lawyer, a soap maker. Imagine, Mao, “three stages of personal hygiene” and whatever. It was not to be. But he eventually gets an education degree so he can go off and be a primary school principal.

Imagine setting your child off to the psychopath doing show and tell. It’s not ideal. And then he joins the communist party, and during the first united front, he also joins the nationalist party. And he has very important positions. If you look at his role in the national party, he’s at their central headquarters, and he’s the minute taker. So he’s the fly on the wall listening to everything. And then he’s a stand-in for the head of the propaganda department, which is probably where he learned a great deal about the importance of propaganda.

Here’s what he says early on: “The Communist Party can overthrow the enemy only by holding propaganda pamphlets in one hand and bullets in the other.” And if you look at the original organization chart of the shadow communist government, you’ll see there are only about six departments there. One of them is a propaganda department. If you have no power, words are your initial way into gaining power.

Strategic Communication Framework

I’m now going to use a framework from my wonderful colleagues, Mark Janest and Andrea Du. This is theirs, about analyzing strategic communication in terms of messenger, message, and medium, and I’ll go through all three.

What you see here is a propaganda poster. It’s a wood block print. That’s the medium, and it’s a very easy way to reproduce pictures back in the day. The message is about a model laborer. This is always “emulate us, and do all the nice things he does” with whatever is going on there.

Messengers were the delivery system, the broadcasting system for the communist party. So you got the communist party, but you gotta reach an audience, and that’s what these messengers are doing. And so they go into local areas, and they identify local grievances for attention by the Communist Party, which when it fixes them or fixes somebody, that will generate loyalties and allegiance. So these propaganda personnel would be identifying local bullies to come in and deal with them, organize mass rallies.

During battles, they’re going to double as medics. After battles, they’re going to propagandize POWs. Between battles, they’re helping on troop morale, but what they’re really doing is reporting back to communist central exactly what’s going on.

Civil and military messengers differ. For civil messengers, they would be activists, maybe in the local government, labor unions, peasant organizations, women organizations, any number of these things. And it’s your broadcasting system to reach a population and mobilize it. Military messengers are a little different. Every single military unit had about a twenty member propaganda team. That’s a lot of people. According to Mao, “the propaganda work of the Red Army is therefore first priority work of the Red Army.” This is very different from soldiering in the West.

International Broadcasting System

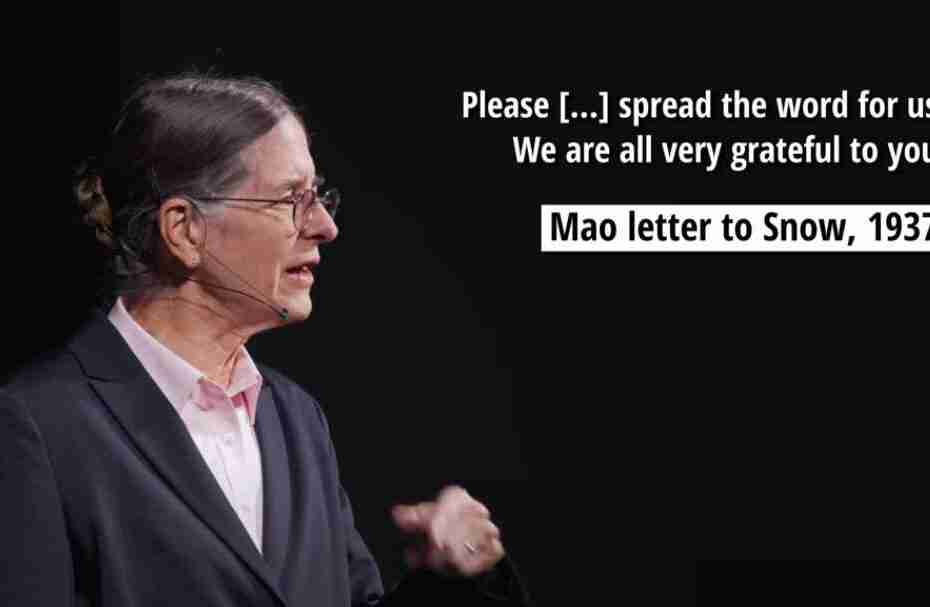

Also, Mao had his international broadcasting system. These would be foreign journalists while Mao was holding court up in Yenan, he invited many of these journalists up there. Edgar Snow was by far the most famous. Why? Because he was the first one in, and then he was the last one out. And he had really long interviews with Mao. And when he was a young man, he never asked, “Why does this A-list political leader spend so much time with me?” That never occurred to Edgar.

Edgar Snow writes “Red Star over China.” You can probably go to Barnes and Noble and pick up a copy there. It’s been in print ever since. And it’s the original footnote in Chinese history because no one knew anything about Mao. And so then everybody starts citing Edgar Snow, and then we cite everybody citing everybody, but actually, it only goes back to Edgar Snow. So, Mao got his word out.

Mao’s Messaging Strategy

Mao thought you want to keep the message simple. You want to make it epigrammatic so that people can understand it rapidly. In his day, this meant having matching slogans to the equivalent of newspaper headlines to provide a lens for people to understand events rather like tweets in our own day.

So when the white terror occurred, when Chiang Kai-shek is turning on the communists in the first united front, the slogan was “arm the peasants.” And then when the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1931, the new slogan is “down with imperialism and the nationalist party too,” because you want to smear your enemy in the civil war while you’re at it there.

Here Mao is one of the most popular poets in China, certainly of the twentieth century. He could write really simple couplets. If you look here, I think it’s a total of eight characters so that someone who’s semi-literate can make their way through this poem. On the other hand, he wrote really complicated things because he needed to garner the support of intellectuals initially before he’d educated enough peasants and workers to take over.

Intellectuals prize poetry, and they also prize what’s called grass writing, which is that unintelligible Chinese writing under there. Mao set these poems to tunes that everybody knew, people could sing them on the long march and elsewhere and learn them that way. So he’s an incredibly accomplished man.

Political Mobilization

He also understood you have to manage the message, and the way he did that is through political mobilization. Part of that is you’ve gotta tell people what the policy objective is, which for him was abolishing imperialism, feudalism, and the landlord class, and then presenting a strategy for how to get there.

Here are the media that he used, not only the written and spoken word, but also the dramatic arts in order to get the message out. And he also used an institutional medium of education. And here is Mao, the primary school teacher, in his element. Most of the people in his armies were illiterate, but Mao knew all about how to reach them.

There are a lot of political commissars. What are they? Political and military commissars come in a pair. Military commissars, the military professional actually knows about the fighting. The political commissar is the one with the direct line to the secret police who will cap the military commissar if there are any problems whatsoever.

So Mao’s got an elaborate network to get the message out, offering all kinds of social services to people, not only medical, but also education for peasant children, and he also educated their parents. This is for the first time in Chinese history. He did this during the winter slack season.

Now the nationalists had also tried to improve education. But once the Japanese invaded full bore, they had to drop it because the nationalist conventional armies are the ones that are fighting off the Japanese conventional armies. The communists are a guerrilla movement, and they’re operating behind enemy lines. So as the nationalists are dragooning people into their armies, the communists are busy offering social services, and I’ll get to land reform. And so for the peasants, before too long, it becomes a no-brainer whom they’re going to support.

Mao also emphasized professional military education because he needs to turn peasants to cadres, to guerrillas, to conventional soldiers. And there’s gotta be an educational pipeline to do this. And if you look at this Northwest Counter-Japan Red Army University, the first four original departments, political work is one of them. This is not professional military education the way it’s done in the West. It’s a separate thing.

Mao the Social Scientist

Now we’re going to go about Mao the social scientist, and here he says, “The peasant problem is the central problem of the national revolution. If the peasants do not rise up and join and support the national revolution, then national revolution cannot succeed.”

If you look further along in his biography, while the first united front was still operative, he’s heading the Nationalist Party’s Peasant Institute in Guangzhou and also their central commission on the peasant movement, learning a great deal about it. But once the White Terror hits, he needs to get out of Dodge fast or they’ll kill him. And that’s where he flees to Jiangxi province to the Jiangxi Soviet, where he is going to become the political commissar of the fourth army. And he’s also going to be in charge of land reform as he figures out how to calibrate that to make it work.

For Mao, he’s doing data-driven survey after data-driven survey. He does a whole series of them between 1926 and 1933, and he’s trying to figure who owns what, who works for whom, who kills where, and the inventories down to the last pitch work and last chicken as he’s trying to establish what is really going on in the countryside.

What he concludes is that six percent of the rural population owns eighty percent of the land, and eighty percent of the population owns only twenty percent. And his solution is going to be revolution. And he goes further into the statistics. He identifies seventy percent as poor peasants, twenty percent who are like his father. They till their own land. They’re middle peasants. And then there’s the exploitative ten percent who don’t get their hands dirty with anything.

What Mao is trying to figure out is how you can incentivize eighty percent of those people into actively taking part in the revolution. This is the key. And what he wants to do is take the bottom of the social pyramid and mobilize it to crush the top of the pyramid.

Land Reform Strategy

The way he’s going to do this is by determining class status through a land investigation movement, which he says is “a violent and ruthless thing.” We’re going to talk about class, approval of class status, confiscation of land, redistribution of land in order to invert the social pyramid. And he’s got a real plan for doing it.

He argues that land reform is just essential for peasant allegiance. This is how you’re going to get it, to draw these hundreds of millions into supporting the communists, but you gotta do it sequentially. You gotta propagandize first, and then you’re going to distribute land later.

He had a very bureaucratic way of redistributing land. The approval of class status, he said, is a life and death decision for the person in question. And so it starts out with a vote at the local level, and then it goes through many layers of party approval before being sent back to the local level to announce who’s going to get the land and who’s going to take a bullet.

Then Mao leverages the enthusiasm of this movement for the people who get the land (the other people not so much). He’s going to leverage this enthusiasm to get people to join the party and also to join the army.

Mao is planning to collectivize all land. That’s what the communists are going to do. But he says, “The system of landlords and tenants cannot be completely destroyed yet.” And because he needs the peasants to join him, and the peasants desperately want land, Mao gives it to them, and he gets a great deal of support for doing this.

But he also keeps the rich peasants around too. This is a deleted portion of the collected works because “rich peasant production is indispensable” until he wins the civil war and can then turn the guns on them. And he’s also got a duplicitous program for the middle peasants. It’s a big bait and switch. It looks like you’re going to get the land, and, well, now you do, and now you don’t. Because at the end, they’re all going to lose their land.

In order to reform, to get the land, Mao is talking about a red terror to get it. While he was still with the nationalists, he wrote a report on the peasant movement in Hunan, where he’s talking about taking all the land from the landlord class and shooting them, and that won’t cut it with the nationalist army because their officers are landlords. So as part of this program, it’s not just land reform and educating people, warm and cuddly. It’s also coercion.

Mao the Military Leader

Now we’re going to do Mao the military leader. And you’ve probably heard this chestnut from Mao, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

Mao’s Early Career and Strategic Vision

Mao spent his early career being right, but holding a minority view about military operations that was not shared by communist central. Mao kept following that dim light wherever it may lead, and events eventually vindicated him. He survived a variety of encirclement campaigns, but then he had some troubles.

Here are his critics. Lily San was a labor organizer. He was the de facto head of the communist party from 1928 and 1930. After the White Terror on the northern expedition, Moscow had told its communist buddies in China that the next thing to do was to take the cities. Li Lisan tries this with the Nanchang uprising in 1927 – total disaster. He tries it again in 1930 with the Changsha uprising, another disaster, and that gets him into exile in Russia.

According to Mao, comrade Li Lisan did not understand the protected nature of the Chinese Civil War. Li Lisan was trying to fight the decisive, war-winning battle far too early. You try to do that, and you can get yourself ruined.

Here’s another critic, Xiangyang. Mao was in the Jiangxi Soviet, and he thought his smart strategy was to lure the enemy into your own terrain, which is favorable to you. Let them get exhausted, then you spring the trap, and you annihilate them. Communist central in Shanghai thought this was nuts, that you shouldn’t be ceding territory at all.

For the longest time, Mao was off in Jiangxi while they were in Shanghai, a long way apart. Communist central couldn’t do anything about it, so Mao did his own thing. Eventually, communist central sends Xiangyang to Jiangxi Soviet to fire Mao personally, which you can imagine didn’t work well for his later career. He fires Mao, and this is where his strategy winds up producing the long march, the long retreat in which they lose ninety-five percent of their people by trying to defend territory.

People began to realize that Mao may have known what he was doing. On the long retreat, Mao chose as his terminal point Yenan, way up north in Muslim and Mongol lands, but near the Soviet border. Mao thought that was essential because the Soviets were their big benefactor. Meanwhile, Zhang Guatou, who was the military commissar of the fourth army, thought nonsense. He believed they should be in Han lands since they were Han Chinese, so he wanted to go into Western Sichuan, which he did. He suffered a series of defeats over 1935, and as a result, he was never as important ever again and eventually defected to the nationalists.

Mao had proven himself prescient, right, and determined, and people eventually recognized that.

Mao’s Philosophy of War

Mao and Clausewitz define war somewhat differently. Clausewitz has this famous line: “War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.” Mao says no, “War is politics by other means.” It is something that is used to achieve political ends. So far, that’s not incompatible.

But here’s Mao’s twist: “A revolution is an uprising, an act of violence whereby one class overthrows the power of another.” Clausewitz is not about class warfare at all. In fact, his wife was always trying to wine and dine the aristocrats – completely different in that department.

Mao looked at the world and believed the linchpin of the social order were landlords, and he was going to detonate them and try to destroy them. He talked about the violence of all of it, that you’re going to get the peasant masses to overthrow these landlords, and that this would require terror in rural areas, but this was absolutely necessary. Of course, this is what the nationalists absolutely would not tolerate.

Mao also understood he was operating in a period of nested wars: the civil war with the nationalists and the regional war with Japan. Pearl Harbor comes a little later. He talked about defeating Japan in three stages. He said defeating Japan requires three conditions: First is progress by China (the civil war, which is the basic and primary thing). The second is difficulties for Japan (the regional war). And the third is international support (the big friend).

Base Areas and Military Strategy

In order to win the civil war, Mao believed you need base areas. The Soviets were often located on the boundaries of provinces and in very difficult terrain where provincial authority, let alone national authority, simply did not extend.

Mao thought that there were certain prerequisites for a good base area, and one is strategic terrain. It’s got to be defensible so that the weaker communist forces can defend it against conventional nationalist or conventional Japanese armies. You need to have a strong red army presence there to make it work. You need numerous organized workers and peasants – you’ve got to have some local support there – and then you need a good party organization.

He believed that you needed to match your military unit, the type of military unit to the territory. He said there are three kinds of territory: base areas, enemy-controlled areas, and the interface in between, which is where guerrilla forces are going to be roaming. He was all about deploying the Red Army to the comparatively safe base area for protection. You might send guerrilla detachments to some of the guerrilla areas, but only really small units would you ever send into enemy territory.

Moreover, he has prerequisites to fight. There are six possible prerequisites – you’ve got to have at least two before you fight. The most important one is that people have to actively support you. You probably need a base area to pull this off. He said that the last three things about enemy weak points, enemy exhaustion, enemy mistakes – those things could appear quite rapidly, but you better choose your terrain very carefully. Terrain is immutable.

He also said that if you’re weak, the way the communists were, you had to follow a strategy of annihilation. What you do is you annihilate one small enemy unit at a time, and the cumulative effects will eventually change the balance of power. Only someone who is really strong can tough out an attrition strategy.

Triangle Building and Guerrilla Warfare

Mao focused on triangle building in these areas. Little guerrilla detachments go out into the interface. If it works out well, and it looks like they can start either a new base area or expand an existing one, that’s what they’re going to be up to. These guerrilla forces are either a disposal force, which you could send out to do risky things, and if they get wiped out, it doesn’t endanger base area defense, or they can become a nucleus of a new base area.

In small guerrilla groups, party members are toughened, cadres trained, the party government mass organizations are consolidated. If they’re successful, then you bring in the Red Army to do higher level institution building and either greatly expand an existing base area or form a new one.

Mao had two military services. Not Army, Navy, Air Force – it was guerrilla forces versus conventional forces. Guerrilla forces operate in the rear of the enemy so that there’s no stability or security. In fact, there isn’t even a front line – it’s just so amorphous.

Guerrilla forces are supposed to be exterminating small enemy forces, weakening larger ones, attacking enemy lines of communications, establishing bases, forcing the enemy to disperse, but they’re doing all this in combination with conventional forces. Because here is the thing – you think about Mao and its guerrillas, but actually, here’s what Mao really says: “Regular forces are of primary importance because it is they who alone are capable of producing the decision, like winning the war. There is in guerrilla warfare no such thing as a war-winning battle.”

Mao also thought that you needed to establish a fire escape if you had a base area. If it all goes south, where do you go? His terminal point of retreat for the long march was up in Yanan. He thought it was important to figure those things out in advance.

Building Unprecedented Alliances

Mao cultivated an unprecedented group of allies never before assembled in Chinese history – not only peasants, but women, minorities, youth, intellectuals, and most creatively, the enemy army.

For cultivating the allegiance of peasants, it wasn’t just education and land reform. It was also army discipline. This is where the three rules, six points for attention, and a couple additional points, which were enforced through 1949 when the communists win the civil war. Why? You don’t want to alienate the peasantry. These are the people that are forming your cadres, your guerrillas, everything. So maintain army discipline.

Mao also took an incredibly forward-looking view about women. Here he is with his fourth wife, the actress. The other three had suffered respectively abandonment, execution by the nationalists, and commitment to a Soviet psychiatric ward – not for the faint-hearted.

But Mao calculated that women are about half the population. They’re miserably treated, so they’re naturals for wanting a revolution. They’re a force that will decide the success or failure of the revolution. He calculated correctly, and he was way ahead of his time. He also understood that in a guerrilla war, you’re sending all the guys off to be fighting, and you’ve got to be building base areas and things, and this is where women came in to do those activities. As a result, he offered women the unthinkable, which is men and women are absolutely equal. Women have the right to vote, be elected, participate in the work of the government. He’s just way ahead of his time.

Mao also offered minorities the previously unofferable, which was self-determination. What the minority people didn’t get is that a promise made in a really desperate civil war with a regional war overlaying it – once you win those things and you could turn your guns on those trying to secede, that promise may be unenforceable. You can ask the Tibetans and Uighurs how it all worked out.

Disintegrating the Enemy

Mao had a strategy of disintegrating the enemy army. In every county, you select a large number of workers and peasant comrades, people below the radar, and then you insinuate them into the enemy army to become soldiers, porters, cooks. You can use women to do this as well – people who are below the radar. You’re creating a nucleus of a communist party to erode them from within. Eventually, it’ll have a shattering effect.

He said also part of this disintegrating the enemy has to do with leniency. Sun Tzu advocates never put your enemy on death ground. Death ground means that you have no hope – you’re a dead person if you don’t fight. So your only hope is to fight. If you put someone on death ground, they tend to fight with incredible willpower.

Mao said don’t do that. When you capture people, propagandize a little, recruit the willing, but release the unwilling so that the comparison of communist leniency and nationalist brutality becomes absolutely stark in this otherwise pitiless war.

The Regional War with Japan

Mao made a really thoughtful assessment of what were the key characteristics of China that would determine what kind of military strategy to use. This is his assessment: China’s a large semicolonial country, an undeveloped country. Second, its enemy is really strong. Thirdly, the Red Army’s weak. And fourthly, there’s an agrarian revolution going on.

From this, he concluded that revolution was definitely possible, but it’s going to take a long time. So he didn’t kid himself about quick wins. He came up with a strategy for protracted warfare.

He thought that Japan had certain weaknesses that the communists could leverage. For instance, the Japanese had inadequate manpower to garrison a country the size of China. This meant that guerrillas could roam far and wide behind Japanese lines. Also, the Japanese were brutal, just gratuitously brutal, and they’re outsiders. This means that the peasantry are naturally going to gravitate towards the communists regardless of what the communists do, simply based on what the Japanese are doing.

Also, the Japanese had grossly underestimated the Chinese. As a result of underestimating the Chinese, they made errors. When they made errors, they started quarreling among themselves and making more errors, and the communists could leverage these things.

Three Stages of People’s War

Mao’s most famous paradigm theory is his three stages of people’s war:

1. The strategic defensive – the prevent defeat phase

2. The middle phase 3. The strategic offensive – the deliver victory phase

In the first phase, you’re focusing on the peasantry. In the last phase, you’re annihilating the enemy army. If you look at activities that go on in each phase, the activities of phase one and two never cease. Rather, you add additional activities as confidence increases.

In phase one, you’re doing popular mobilization, base area building, triangle building, guerrilla warfare. Then as you get more of these things, you can start engaging in mobile warfare, try your hand in a little conventional warfare, reach out with diplomacy. And then if you go further in stage three, then you’re talking positional warfare, and you’re going to have the war-winning battle.

Mao’s Strategic Evolution: From Guerrilla Warfare to Conventional Power

Well, the transition from phase one to two is basically you have a critical mass of base areas, cadres, armed forces that you can move into phase two. But the problem of being in phase two is what looked like isolated acts of banditry in phase one to the incumbent government now becomes clear. The incumbent government gets it, that they’re facing an insurgency bent on regime change and the regime changes strategy. And so the communists are no longer under the radar, but they’re in the crosshairs. It’s dangerous because they’re weak and the enemy is strong.

So when you transition to phase two, initially, it’s quite dangerous. Here’s Mao writing about these problems and saying, look, in stages one and two, the enemy is trying to have us concentrate our main forces for a decisive engagement, i.e., decisive in their favor that when the works, they’ll annihilate us. And, of course, this is what General Westmoreland was trying to do in the Vietnam War – getting the North Vietnamese to concentrate so that he could blow them off the map. And, of course, they’d read their Mao and didn’t do that nonsense. So, Mao is saying you only fight when you’re sure of victory.

Also, in order to get to phase three, you need a big friend. Why? Because phase three is conventional warfare, which requires infinite supplies of conventional armaments that requires an industrial base to produce it. And somewhere like China lacks this industrial base, and so, good old Soviet Union played this role the world over. And so this is the secret sauce of people’s war.

If you want to get to phase three, you need a big buddy, and that’s where the Soviet Union came in. And so this is why Mao determines that Yenan’s going to be his terminal point of retreat. He’s finding his way through to the Soviet Union. No kidding. You gotta have the conventional arms to fight this stuff.

The Reality Behind Mao’s “People’s War”

What’s interesting about Mao’s description of people’s war is it actually applied not so much to the war with Japan, which he claimed it applied to, but rather to the civil war with the nationalists. And here is the key. Mao didn’t actually fight the regional war against Japan. The nationalists did. The nationalists did every bit of the conventional fighting except one, and that’s the Hundred Regiments Campaign that Mao fought in North China in 1940, and he was smeared.

The Japanese responded with a “Three Alls” campaign, which is “kill all, burn all, loot all,” which is what they did, and it wiped out loads of Chinese communist based areas in North China. So Mao never tried that ever again, and he certainly didn’t write about it in his collected works. You know? Don’t talk about failures there. So it’s interesting what he’s talking about really applies to the civil war.

And Mao understands these different layers. So as the nationalists are busy fighting the Japanese and actually being destroyed by them, the communists are pretending that they’re fighting the Japanese. They’re later going to take credit for it and say, we won against the Japanese, which is nonsense. There was also the United States in that as well. Because he’s using that to strengthen the communist during all of this, both rural mobilization.

So when Japan’s defeated and the communist, when civil war resumes full bore, he’s in a good situation. Okay. That’s it on Mao, the operational military leader at the operational level. Now let’s put it all together as Mao, the grand strategist of linking all elements of national strata power into a coherent strategy.

Mao’s Instruments of National Power

These are Mao’s instruments of national power: The peasantry, propaganda, land reform, base areas, institution building, warfare, and diplomacy. The US military, when they’re thinking about elements of national power, love this little framework DIME because the D is for diplomacy, I is intelligence, M for military, E for economics as being critical elements of national power. Look. It’s better than only looking at the military elements. At least you got three more things.

But if you look at what Mao did, this is not a cookie cutter event. This is a different society, different national elements of national power are available. You’ve gotta get to the other side of the tennis court net to see what the other team is doing. Alright. Mao is famous for all these reasons, but also for his sinification of Marxism, where he makes all the things that I’ve told you about.

It makes his version of Marxism much more applicable to these countries, the newly independent countries after World War II of how they put things together. And he positions himself to replace Stalin who dies in 1953 as the leader of communism. So Mao was prescient on numerous levels. He was certainly prescient about the centrality of the peasantry. He was way ahead of his times on the importance of women.

He was calculating and cunning on how he was going to use minorities and POWs. He had proven his coup d’oeil and determination with his military strategy. He also anticipated when the Japanese war in China would stalemate, and he also anticipated more or less when the United States was going to get into the war in Asia. And he’s a great sinifier of Marxism.

Mao’s Revolutionary Concepts

Mao produced all kinds of concepts and paradigms that are useful for insurgents who are trying to take over the host from within. And I’ve listed all a variety of them here, and I’m going to go through them in turn. And these are the things that the counterinsurgent then has to counter.

# Rural Mobilization

This is obviously a big deal in Mao. And if you compare – I’m going to be doing a lot of comparisons with the Vietnam War and the Korean War because they’re communist and all these things. And, you can see Mao’s rural mobilization was very successful in China. The North Vietnamese rural mobilization was also really good. South Korea, not so much.

Why? The leader – I mean, of North Korea trying to mobilize the peasantry in the South. That wasn’t so successful. And why? Sigmund Rhee, the leader of South Korea, immediately did land reform.

And, this glues loyalty of soldiers to the leadership doing this, and maybe that is not the only factor, but an important factor for why the Korean War turns out differently.

# Base Areas

Mao’s base areas are really important. The North Vietnamese used them to great effect. They had all kinds of areas in the South and then on the borders of South Vietnam. North Korea, not so much. It couldn’t form base areas in the South. Why? It’s a peninsula, which the US Navy cut off. It’s also cold.

So where are you going to flee if you want to do a base area? I think it’s up a mountain in South Korea, and that will get cold in the winter, and you’ll probably freeze to death. I believe Al Qaeda means “the base.” That’s the correct translation. So if you’re thinking about ISIS or whatever’s left of it, you can go back to Mao’s ideas about base areas that you need a particular kind of geography that’s good for the defensive, kind of a big party organization, a lot of local support.

You gotta have military forces there. Does Al Qaeda – well, it’s ISIS or something – do they have all four of these things, or can you remove any one of them?

# Luring the Enemy In Deep

Another idea from Mao is luring the enemy in deep. And Mao had done that very successfully in the first three encirclement campaigns, and then he was removed from command, so he wasn’t doing that anymore. And, again, in the final phases of the Chinese civil war, the 1945 to 1949 event, Mao lures the nationalist deep into Manchuria. And then the nationalists are a South China phenomenon. Right? I showed you the map.

Chiang Kai-shek starts in the south, and he goes way up north. So he’s weakest in the north, but Mao lures him way up there in Manchuria, and then he springs the trap and destroys Chiang Kai-shek’s armies up there, and then the entire civil war wraps up within a year of that. So, Mao also lured good old General MacArthur who fancied himself a great Asianist in the Korean War. MacArthur goes all the way up to the Yalu River right on the Chinese border in the Korean War, and then Mao springs a trap. And MacArthur didn’t realize that a – I don’t know – 350,000 Chinese troops had been infiltrated around him. Oops. Missed that. It did not work out well.

But for the US Navy now, needs to think about what about being lured into the South and East China seas and then the Chinese pulling the trap. There are places you don’t need to go. The Chinese may have to go there, but maybe you don’t have to.

# Terminal Point of Retreat

Another one is terminal point of retreat. I’ve talked about Yenan being a really good one, and that worked. And then when the Manchurian campaign initially wasn’t going well for Mao, he retreated up to Siping, which is a little bit north, and that worked well enough.

But when Chiang Kai-shek tried to pick these Manchurian cities as a place to retreat in Manchuria, bad news. There’s only one railway system that gets you south out of Manchuria. You suppose the communists don’t know about it. And, they encircled the nationalists in these cities and destroyed them there. So when you’re thinking about things, think about, well, if you knock them out of one area, where might they go next?

Disintegrating Enemy Forces

Another concept from Mao is disintegrating enemy forces, which is what happens to the nationalists. Think about it. Chiang Kai-shek had been fighting since the 1920s and forever and ever, and he fought the Japanese. They’re brutal.

The United States had trouble fighting the Japanese, and Chiang Kai-shek fought them alone for a long time before we joined the war. And yet, he loses a battle in 1948 in Manchuria, and that’s it. The rest of the country wraps up. So what was going on there? Or the South Vietnamese, they’ve been fighting forever, and then the whole place just wraps up.

And the same thing with Japan in World War II that, they’ve been fighting all over the place forever, fighting us, brutally. And then in 1945, we don’t even have to invade the home island. Think how unusual that is. The Germans fought every street on the way to Berlin. The Japanese quit.

And this is about disintegrating the enemy and why it happens. But what you can say in all those three cases is the warfare had been going on for an incredibly long time, and it was ruinous, and the places in question were ruined. So don’t expect that to happen too fast.

The Three Stages of People’s War

And, of course, Mao’s big contribution are his three stages of people’s war. And Mao presents them as sequential. You go from one to two to three, and ta-da, you win. And they’re cumulative. Right? You do certain things, and then you get to phase two, and you’ve had this cumulative effect of destroying enemy forces, and you’re getting more accumulating casualties on the other side and finally win.

A student of mine said that’s actually not a great way to look at it or an even better way to use it is like a metric of how an insurgency goes up and down so that ISIS may be on the cusp of going into stage three. I don’t know if they have really – well, possibly with all the equipment they got initially, or whether then they get knocked back to stage one where you wonder whether they still exist anymore and come back and forth. Anyway, that was that person’s take. I thought I’d pass it along to you.

Mao’s Dualities

Alright. I have one last thing to talk about Mao, is that when you read these seven thousand pages, and I don’t recommend it, one is struck by all these dualities.

And I think it goes back to yin and yang analysis, which is very prominent in traditional Chinese thinking. So if you look at Mao discussing triangle building, it’s in terms of the presence or absence of factors, presence, absence being opposites. So you’re going from the absence of political power to the seizure of political power, from the absence of the Red Army to the creation of the Red Army. It goes on and on that studying the differences and connections between dualities is the task of studying strategy, and it’s really everything.

So to defend in order to attack, to retreat in order to advance, it goes on and on, and it’s all about correctly orienting yourself between these opposites. So oppose protracted campaigns and the strategy of a short war. Uphold the strategy of a protracted war in a short campaign, and I’m starting to lose it. And you’ve gotta put everything in the context of each other, losses, replacements, fighting, resting, concentration, and dispersion. And I’m thinking, I don’t get this. Mao’s bipolar disorder.

So I went to this gentleman, Brigadier General Samuel B. Griffith. He is the only translator into English of Sun Tzu who has a distinguished military career. And, also, he went on to get a DPhil, it’s like a PhD, from Oxford in military history. And if you look at his career, he’s in China during the Japanese escalation of the Sino-Japanese war.

He’s back in China, does another tour at the end of the Chinese civil war. He gets top marks in the military’s Chinese language exam. Oh, look at these details. Navy Cross, Purple Heart, Distinguished Service Cross. He’s a distinguished man.

And for retirement, he decides he’s going to go get the Oxford degree, and he writes the translation of Sunzi. He is the only translator of Sunzi who translates as “death ground.” Other people is like, oh, I don’t know. I can’t remember the words like, I don’t know, contested ground, something else. But I’m guessing that when he chose those words, death ground, it’s because when he was thinking about it, it might well have conjured up his memories of what exactly it was like to be on Guadalcanal or New Georgia.

Insights from Griffith’s Translation

So, he has provided insights. Oh, also, the other thing to mention about him is he’s really modest. I had to dig around to find these biographical details. They’re not on the cover of his book where they should be. And his service to his country continues to this day because it’s his translation that continues to educate officers now, what is it, over forty years after his death.

But here’s his take. In every apparent disadvantage, some advantage is to be found. The yin is not wholly yin, and the yang is not wholly yang. It is only the wise general, said Sun Tzu, who is able to recognize this fact and turn it to good account. And, of course, Mao could, and he did.

But in peacetime, choices are not binary. They’re graduated. And evolution is much more conducive to economic development than revolution.

Q&A Session

DWARKESH PATEL: So here’s something I’m confused by. You were talking about Mao as a shrewd commander, somebody who had studied not only the military, but had also compiled these rigorous records of farm life and agriculture and everything. And then you fast forward to when he’s in power and you go to the Great Leap Forward. And some of the things that he was doing, it just you can’t imagine that somebody thought this is a good idea, that peasants would take off the harvest, wouldn’t attend to the crops, but they’re going to make iron in their backyards. They’re going to shoot the sparrows, you know, have a locust infestation. How do we square this shrewdness in the beginning and this idiocracy level ideas in the Great Leap Forward?

SARAH PAINE: Well, first of all, you need to think about what his objective is, which number one is stay in power. Right? And number two is probably Communist Party in power and his visions of revolution. So that’s one thing. So then you’re worried about welfare of people as if that’s the primary objective. It most certainly is not. And then he may have assumed that it came along with these things, and that’s a whole problem with communist ideology is people don’t believe it because they know it’s wrong. They believe it because it’s right.

And there’s a whole problem with that about labor theories of value and things that turns out there are things called services that are also valuable. And so the basic theory that he’s implementing is incorrect. It just takes the communists a little while. Some of them haven’t figured it out, but takes them a little while to figure out their parts that don’t work.

But there’s a whole other piece to him is I think about our own world. How much expertise does any individual have? It’s amazing. The man reunited a continent, and he did all those things. And then to expect him to then run a peace-time economy is crazy, but, of course, he wants to do it. So he stays there.

Or think about, like, in Britain, Winston Churchill, great wartime leader, but he was booted out of office right after that war. If you think about different capabilities of people. So, don’t expect one individual to do everything. So that’s a whole other problem.

So when Mao’s running stuff from afar this is a country with how many people? It hadn’t hit a billion then, but it’s hundreds of millions. And it’s been shattered by warlord rule forever. And so how are you going to extend central control to the countryside? Really tricky. I suspect that’s why he puts them on communes because it lines up with communism, but it also lines up with party control. Because if you put all this vast population, because most people are peasants, on communes, then you control whether they eat or don’t. You truly control them.

So it’s those factors. It’s so big. When you start putting a policy in place from Beijing and then how that actually fans out over the whole country, it’s got to be a mess. Different localities and things.

DWARKESH PATEL: But when I compare him to other, even other communist leaders…

SARAH PAINE: Which one?

DWARKESH PATEL: So if you look at Stalin, for example, yes, he causes the Holodomor. Right? Three million people die.

SARAH PAINE: Details.

DWARKESH PATEL: But that was an intentional famine where he was trying to root out the Kulaks. The Great Leap Forward was, like, he wasn’t trying to kill tens of millions of Chinese. And there’s instances in the twenties where Stalin threatens to resign, and people close to him, the Molotov and others say, you can’t do it because nobody else can run the government like you can.

SARAH PAINE: True. But the level of… It doesn’t seem like Stalin was a devoted communist and that led to many deaths, but it didn’t seem he didn’t seem deluded in the same kind of way that Mao was.

First of all, Russia is quite a developed country compared to China. And if you think about it, Russia had been industrializing since the late nineteenth century, and China’s a much later event. Russia also has all sorts of institutions and things that China was lacking. So already, Stalin has many more tools at his disposal than what the Chinese communists are going to have.

Also, the kind of warfare think about the warfare in China. And you got the Taiping rebellion. It’s only the biggest of the peasant rebellion to the nineteenth century. And I can’t remember people estimate I can’t remember if it’s twenty or thirty million people. That’s a large number. Right? Because I think World War II is supposed to be, like, fifty-five million.

So this is there are a whole series of these peasant rebellions in the nineteenth century that go on for, I don’t know, twenty-five, fifty years. If one’s here, one’s there. They by the end of it, they’ve basically devastated parts of every province. And then you overlay this with the warlords coming in and all of that, overlay that with the communist nationalist thing, overlay that with the Japanese, you’re talking about a massively trashed country.

And think about it. I’ll give you another example. For Americans in the room and for others who aren’t Americans, you have to based on your dealings with Americans, the country had a civil war. It ran, what, four or five years? It was mostly in the south. Northerners came, joined armies, and they went to the south. The institutions of government didn’t change in Washington. They certainly did in the confederacy, but those were new things. Right? Because they were trying to secede.

And, many of the losing side of that war still hasn’t gotten over it. Right? So if that’s what’s going on here and that thing wasn’t nearly as brutal as the kind of civil wars. At the end of the civil war, who gets, Lee’s army is allowed to go home. They aren’t shot on-site, which would be the kind of thing that went on in the Russian civil war, Chinese civil war. So if that kind of bitterness and unsettledness is still present in this highly institutionalized wealthy country, this one, you better believe China’s a mess.

So then when you’re wondering why Mao can’t surf that wave, no one can.

DWARKESH PATEL: Just to linger on this. Even if he’s not a specialist on agriculture and even if China is a hard country to govern, he was somebody who was shrewd in the sense of when these battles are happening. I imagine if somebody came up to him and said, we’re winning these battles, and it’s a total fabrication. They’re in fact losing these battles. He would have been quick enough to realize, listen. This is just wishful thinking. I realize you’re just trying to make me feel good, but this is a lie, and I’m not going to stand for it. Whereas if you go to the Great Leap Forward, people will millions of Chinese are dying, and they come to him and say the grain harvests have never been higher. And he’s like, great. Let’s export our grain. And just this ability to have this basic discernment of what is actually going on, that true state of affairs is gone.

SARAH PAINE: There’s another… Mao doesn’t become canonized as Mao, or I’m mixing metaphors. The emperor of China until victory in the Korean War. So in the early period, a lot of there Mao is supposed to have written this book called “On Guerrilla Warfare.” It is not written by Mao. It took time to figure it out for outsiders. It’s written by Peng Dehuai and others, his generals. And so there were many people’s ideas that went into winning the civil war. It is not just Mao.

It’s and then he winds up purging these people later. And so it’s not until after the during the Korean War, he’s busy purging everybody massively because he can use it as a big excuse. Right? We got this war. We don’t want to hear from these people. And so he has purged more and more and more and more people so that there are fewer and fewer counterarguments. It’s a real case against dictatorship. For all the chaos of party politics, you’re at least you’re forced to confront the counterargument. It is a healthier situation to be in.

Post-World War II Outcomes

DWARKESH PATEL: Let’s go back to the end of World War II. Okay. So if you look at basically all the main actors, none of them get even most of what they want. Some of them get the exact opposite of what they want. Germany and Japan initiate to expand their territory. Both of them end up with the smallest territory they’ve had in a long time. Britain starts the war or not starts, but enjoins the war in order to defend Poland. Poland ends up in totalitarian occupation afterwards, and the British Empire disintegrates. But Stalin ends up with the borders of the Soviet Union vastly expanded. China becomes communist. How do we make sense? Is Stalin just like a master strategist here?

SARAH PAINE: Oh, I believe there’s a detail of how many tens of millions of Russians died on that thing. But a great personal success for him. It’s numbers of Russians who were destroyed in that are incredible. So, okay. For dictators, yeah, they can have personal successes.

I think more it’s in these horrible wars that dictators can rise. Also, great depressions provide hothouse conditions for dictators. So, yeah, I think the lesson is the last thing you want to do is fight a world war. But, as Britain discovered in World War II, if Hitler’s insistent, you’re stuck. Right?

It might be a lesson for our own day. Right? Isn’t this Ukraine’s problem? They didn’t want to fight a war. What are you going to do? Putin launched. We don’t exactly want to fight a war. Well, what do you want to do? Let Putin do whatever he wants for forever for however long he wants?

The reason that you all are prosperous is there’s a global maritime order in which people obey rules because it is so much cheaper to obey rules. Because what do you do when people break the rules? You hire a lawyer. It’s not protection money or starting to blow up each other’s buildings and destroying wealth at an incredible clip is which is what you’re seeing going on in Ukraine.

So these things are consequential. None of us makes all the choices. And when other people make bad choices, you’re stuck responding to them.

DWARKESH PATEL: Before Mao before the communists completely won the civil war, did people anticipate how truly how terrible the communist power would end up being in China?

SARAH PAINE: I doubt it. I think, communism was a new thing. Right? So you’ve got it going on with the Russians. I mean, the nationalists were telling us that it would be like this, and we looked at them and go, what could be worse than the nationalists? Because they were desperate situation with all what the Japanese were doing, and then they get blamed for it all. There can’t be something worse than that. What we call communists. But, I don’t know that anyone could have predicted why you can anyone do a crystal ball what the world’s going to be like in ten years?

What it seems and when you read the history books that it had to be that way, and yet in our own lives, we know that it’s contingency of why things turn out as the aggregate of all of our choices. How would you ever calculate that?

DWARKESH PATEL: I wonder if there’s a lesson in there that America should be more open about supporting corrupt, somewhat autocratic regimes because especially when they’re facing, fanatical ideologues because things really can get much, much, much worse.

SARAH PAINE: I think Americans need to worry about overextension. Any country has to worry about overextension. We have finite resources. Also, you’re talking about sending your fellow Americans to go get themselves killed. And that’s quite something to ask someone to make that kind of sacrifice. See, it had better be worth it. Right?

And so there are three hundred million Americans. Well, the world’s got eight billion. Be cautious. And it’s what’s key on this maritime order, the big insurance policy of it all is our allies and institutions.

The United Nations and International Cooperation

This is the great gift of the greatest generation of having created the UN, which is how many millions of lives have been saved from polio vaccines and other things that come through the UN. Do not dismiss these organizations. They’ve done a lot or the EU. Work through these things and listen to your allies. They’ll have insights, and there’s power in allies.

DWARKESH PATEL: Tell me who China’s allies are. The crazy man in Korea who can’t even feed people in the twenty-first century? Although he certainly feeds himself, but that’s a whole other story. I mean, it’s incredible. Who are China’s friends?

SARAH PAINE: I mean, Iran? A theocracy? I mean, talk about passé. Who does theocracies anymore? Okay. The Iranians? Okay. Good on them.

Post-WWII Support and the Chinese Civil War

DWARKESH PATEL: So after World War II, the Soviets are giving the communists in China tremendous amounts of leftover weapons from the Japanese, a bunch of other goods, supporting them tremendously. At the same time, Truman had an actual arms embargo on Chiang Kai-shek in 1946. The Marshall Plan for Europe is thirteen billion to help build up defenses against communist appeal. At the same time, Truman has to be forced in 1948 by Congress to give a couple hundred million to China, literally one-hundredth of what was given to Europe. And by that time, it’s too late for Chiang Kai-shek. If you just look at that record, it seems like we’ve abysmally messed up after World War II in helping the nationalists stay in power. Right?

SARAH PAINE: Do not exaggerate the capabilities of any one country for openers, but I think it’s really important to distinguish between nation building and nation rebuilding. If you’re rebuilding, which is what happens in Japan and Germany, they already had full-up institutions, modern economies before the war. They had no problems with educational institutions going all the way up, judicial institutions. They had competent police forces, competent parliaments and other things. So when you give Germans some cash, they know exactly how to recreate things and rapidly produce modern institutions.

You’re talking about China. They never had these institutions. There is no indigenous expertise. Oh, and by the way, what’s the literacy rate in China compared to Japan? Woah. No one reads in China, and everyone reads in Japan. It’s not quite that bad.

We’ve had this problem in Iraq and Afghanistan. So we decide we’re going to do the debaathification thing, and then we think the police are going to still show up and work except no. That’s not how it works. They haven’t got these institutions. And so it’s not feasible – a Marshall Plan in China would not have worked.

Also, we had really competent foreign service officers in China in this period. Why? They’re the children of missionaries, and so they spoke fluent Chinese and had a deep understanding of China. And they were saying, it’s hopeless, that there is no way Chiang Kai-shek’s going to win this thing because he’s hated by the peasantry, which he was, for the reasons I’ve told you. Right? If he’s busy pressing them into his armies because he feels he has no choices, whereas the communists are giving them land and educating them, you better believe who the peasants are supporting.

And the missionaries, they were then caught up in the McCarthy purges and were just about ruined, lost their jobs in the State Department and elsewhere only to be exonerated, I don’t know, ten, fifteen, twenty years later when they’ve already lost their careers and who knows how they raised their families.

DWARKESH PATEL: I thought it was the case George Marshall was the envoy to China. I thought it was the case that later on, they realized it was hopeless, and so then they stopped supporting Chiang. But it’s at the time…

SARAH PAINE: Different people realize it at different times. But the reason they didn’t support Chiang as much as they should have was because they thought he was inept. The communists obviously seemed like hopeless underdogs, and it was just thought that Chiang is going to win and therefore, we don’t have to support him.

DWARKESH PATEL: No. No. No. They’re constantly goading the nationalists to form some sort of ceasefire, do some sort of coalition government when in fact what they should have done is like, no. You have to make sure that you keep China.

SARAH PAINE: No. It was considered hopeless. This is called making a net assessment of not what you want it to be, but an accurate one. They believed it was not feasible. Even in, like, 1945, 1946? You’re talking hundreds of millions of people. We can’t even deal with Afghanistan today with, what, twenty million people. It’s not feasible.

It’s at the end of World War II. American GIs are sick of it, as are their parents, of fighting more wars. Europe has been leveled, and there’s this absolute fear that the communists are going to move into Europe, which actually counts for Western economies in those days. The Italian and French communist parties were incredibly strong. So all the focus of limited resources is going to make sure that Europe settles out. And we don’t have infinite resources.

DWARKESH PATEL: I feel like you’d do better than one-hundredth of the Marshall Plan, to keep China from turning communist. And look what the consequences were. Vietnam, we had to fight. Korea, we had to fight. Cambodia, the genocide there.

SARAH PAINE: But you can’t solve all these things. There are things that are not feasible. I’m going to layer on this because you’re an optimist. Anyway, maybe you’re right. But, anyway, you’ve got my take on it, and I can’t prove I’m right. That would be my take.

The Contingency of History

DWARKESH PATEL: I remember in your book, which is to your right, the word Sharasia, there’s a passage where you say there’s so many sort of individual contingent things that led to the communist taking power.

SARAH PAINE: Yes.

DWARKESH PATEL: If any of these factors was off…

SARAH PAINE: Yes.

DWARKESH PATEL: The outcome might have been different. The fact of all these factors, the fact that American support or lack thereof was not one of them. It just seems like it was a super contingent thing, but also America not being as strong as they should have. It just didn’t matter.

SARAH PAINE: It’s just not politically feasible. I mean, put yourself back in those days. You’ve already done a three-year tour in World War II because in those days, you started serving whenever it was in the war, and you weren’t coming home until the war was over. It was none of this nine-month tour or a year tour here and there. It was you’re there for the duration. So you get home, and then you’re told, go make nice to the Chinese and go get yourself killed there. How is that going to fly in your family?

DWARKESH PATEL: Probably poorly. I mean, again, you don’t have to send the GIs there. You can just not do an arms embargo on them.

SARAH PAINE: Oh, I think it was so minor. By then, it’s too late. The great question is some people would argue that in 1946 when Marshall tells Chiang Kai-shek to stop, halt his advance. This is when he’s doing quite well and when I mentioned that the terminal point of retreat for the communists was up in Siping, Manchuria. Some would argue that Marshall should never have done that. He should have let the nationalists go all the way up, and that would have changed the outcome of the Chinese civil war. You can make an argument that that might be true.

The Geography of Conflict

Here’s the counterargument. I don’t know the answer. If you look at a map of China or imagine one, Manchuria is way up. It’s like a salient into communist territory because it’s bordering all the Soviet Union. And then it’s got quite a coastline, but the Soviets had blockaded that. So nothing’s getting in that way. The only way, given the Chinese railway system, is literally one train line connects Manchuria to South China.

So it means Chiang Kai-shek’s movements are incredibly predictable. So one argument you could make, and people have, and I don’t know the answer, is that, hey. That was the big error.

The mistake—and this is a common one that Americans make, so this is worth talking about—is Americans often don’t look at warring parties to understand if they are primary adversaries. There is no way you’re going to make them make nice. So United States had trouble for years trying to get Pakistanis and Indians to cooperate, and it would want to give aid to both of them and just didn’t get it. As long as they’re primary adversaries, you aid one, it infuriates the other, and they’re never going to cooperate.

Or, I suspect what was going on in Iraq and Afghanistan. So you want to have a democracy, and you want to have all the parties represented. Well, if they all want to obliterate each other, the last thing they want to do is have representation of the other side. Right? So if you have parties that want to exterminate each other, the idea of getting them to cooperate is impossible.

So don’t try it. So that would be the lesson from this thing of the we kept trying to do a coalition government with the communists and the nationalists. It’s a nonstarter. But the United States was a very isolationist country and didn’t have the attitude of a great power until after World War II. In World War I, we felt dragged into it and these horrible wars and being quite irresponsible during the Great Depression and just ignoring everybody else’s problems. Didn’t want to hear about it. And then we get a World War II out of that, then we rethink that whole proposition.

Taiwan vs. Mainland China

DWARKESH PATEL: If you had to speculate, suppose the nationalists win, in Taiwan because they’re forced to, they have a very sort of pro-American policy. But if they had won in mainland China, would it have been similar where mainland China just turns into Taiwan, or would it have been different?

SARAH PAINE: No. I’m sure it’d be different. One of the reasons Taiwan is Taiwan is after they lost the civil war and they are on the island of Taiwan, they did a big after-action report analysis of what went wrong. And they decided it was corruption and that it was land reform that they needed to fix those things, but they couldn’t do land reform on the mainland because that’s their officer corps.

But when they come to Taiwan, they can more than redistribute Taiwanese land, which they do, and it’s bloody because the Taiwanese don’t want their land redistributed. And the Taiwanese were given bonds, and they thought those bonds would be like the pieces of paper that were issued in the mainland, i.e., worth nothing. But, actually, after time, they became quite valuable. But land reform was bloody in Taiwan. And today, Taiwan has a very equal income distribution.

The Human Cost of War and Famine